Liberating Logos: Reason, Conscience, and the Future of the West

For more than a century and a half, the specter of secularization has haunted the West. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Max Weber famously spoke of the “disenchantment of the world.” He premised a “rationalization” of the world where “facts” and values” were definitively separated and where “the great enchanted garden” of religious societies was inexorably replaced by a cold and soulless reason. In truth, there was little reason in the traditional sense in Weberian rationality. Reason, in his understanding, could say nothing, absolutely nothing, about the meaning of life. Nor could reason provide any substantive guidance for moral and political choices. Weber was a proto-existentialist, a “scholar” who did not quite succumb to Nietzschean nihilism (witness his faith in an austere and methodologically rigorous social science). And he presupposed rather arbitrarily that the world before disenchantment was ruled by “magic” in various forms, and not, at least in the West, by a capacious reason that coexisted with faith in the divine source or ground of the “natural order of things.”

Spiritually discerning poets provide a better guide to a West haunted by the “death of God.” In his famous 1867 poem, “Dover Beach,” the English writer Matthew Arnold spoke regretfully about the “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” of “The Sea of Faith,” a withdrawal he lamented even if he could not affirm the truth of faith. Arnold placed his hopes in “love,” in the human capacity to “be true to one another!”. This is not nothing. But it is, in the end, rather thin gruel. Arnold’s accompanying faith in “culture,” in a conservative version of liberal humanism, protected him from the temptation of nihilism even if it offered nothing in the way of a renewal of a robust conception of reason and faith. His was a politics of cultural lament. The great twentieth century Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz refused to jettison faith as he too wrestled with secularization and the alleged “death of God.” In The Land of Ulro (1977), he whimsically captured the human consequences of our dual loss of faith in God and Reason: modern man finds himself with only “the starry sky above, and no moral law within.” We are a long way from Kant’s rational faith in “practical reason.”

For his part, the great Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn thought that the disasters of the twentieth century happened because “men have forgotten God,” a forgetting that also entailed loss of confidence in the reality of the human soul where good and evil, and an enduring moral order, orient the choices of men (see Solzhenitsyn’s 1983 “Templeton lecture”). Milosz and Solzhenitsyn self-consciously spoke the language of “good and evil,” truth and liberty. Both spoke of the soul and responsibility before a God who is a friend to all. In their poems, essays, novels, and writings, they did not so much “re-enchant” the world as give us access to a moral order, an order of things, that a rationality worthy of the name must ultimately account for. Their spiritual and philosophical discernment, confronting evil in the form of twentieth-century totalitarianism, reminds us of the terrible self-limitation of modern reason. A reason that cannot speak about the drama of good and evil in the human soul, that cannot see totalitarian mendacity for what it is, that cannot call tyranny by its name, cannot apprehend the human world for what it is. As Leo Strauss argued in On Tyranny, it is not truly “scientific.” As the phenomenologists would say, it cannot “save the appearances.” The positivistic self-limitation of reason cuts us off from reason’s “true greatness,” as Pope Benedict XVI strikingly put it, and leaves us vulnerable to the contemporary “dictatorship of relativism.” We are left with a radical divorce between truth and liberty, authority and subjectivity, one that leaves us to choose helplessly between secular fanaticism, religious fundamentalism, and democratic indifference.

Pope emeritus Benedict XVI, an eloquent partisan of both reason and faith, has sketched a better way in a series of writings and speeches over the last twenty-five years. With his help, I will show that Arnold’s withdrawal of faith ultimately has its source in a crisis of reason, a reason that has limited itself, with grave consequences, to a narrow and soulless instrumental rationality. Pope Benedict is the enemy of every kind of fideism. A faith worthy of the name affirms the liberating Logos, or Creative Reason, at the heart of the universe (this is one of Benedict’s central theological ideas). The Christian God is not an oriental despot, a voluntaristic potentate, whose will alone defines what is right and wrong. Christianity itself does not eschew philosophical inquiry or in any way endorse irrationality.

Like his predecessor Pope John Paul II, Benedict believes that there is something “providential” in the encounter between Greek philosophy and biblical religion (see John Paul II’s Fides et Ratio). Christians are obliged to give a rational account of their faith—apologetics are never reducible to propaganda (on this, Benedict appeals to I Peter 3:15). In his 2006 Regensburg address, Benedict laments the “deHellenization” of Christianity—its reduction to a “humanitarian” religion closed off to a rational articulation of “nature” and “reason.” Christianity is nothing if it is merely a “humanitarian moral message,” an invitation to this-wordly amelioration or revolutionary transformation. Nor is it separable from the “natural moral law” available to reason and conscience. With the help of Pope Benedict’s wonderfully thoughtful and suggestive address to the German parliament or Bundestag of September 22, 2011, I will trace the ways one might begin to overcome the fatal “self-limitation” of modern reason and the “dictatorship of relativism” that accompanies it.

In the Bundestag address, Pope Benedict speaks both as a German patriot and as the Bishop of Rome. His subject is simultaneously moral and political: “the foundations of a free state of law (Recht).” His starting point is practical since every statesman and citizen must wrestle with what it means to act in a just and lawful manner. He begins his reflection with a brief story from sacred Scripture. Let us quote the text at some length:

“In the First Book of Kings, it is recounted that God invited the young King Solomon, on his accession to the throne, to make a request. What will the young ruler ask for at this important moment? Success—wealth—long life—destruction of his enemies? He chooses none of these things. Instead he asks for a “listening heart” so that he may govern God’s people, and discern between good and evil” (cf. 1Kings 3:9).

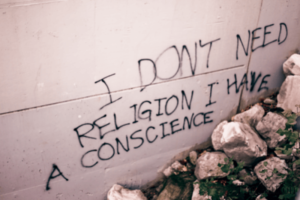

A “listening heart” is a cognitive and moral faculty—it is not a mere source of feelings and intuitions. It is more than a “discerning mind” as some versions of the Bible problematically translate this passage. “A listening heart” gives us access to an objective moral order that transcends mere subjectivity. It is a beautiful poetic rendering of what the tradition means by conscience. Conscience is that indispensable vehicle for connecting our liberty and judgment with truth and reason. Choice is never merely arbitrary, bereft of rational moral guidance. Without the access that conscience gives us to truth and justice, power becomes an instrument “for destroying right,” at best Augustine’s “great band of robbers” and, at worst, the open nihilism of the totalitarians who in the 1930’s and 1940’s drove Germany and the “whole world” to “the edge of the abyss.”

The twentieth century’s experience with Communist and National Socialist totalitarianism reminds us of what happens when we reject the primacy of conscience. The causes of the totalitarian episode were not some intellectual “monism” or “totalizing truth” as our relativists and postmoderns like to claim. This is the weakness of the liberalism of an Isaiah Berlin, one that constantly invokes pluralism, but is afraid to appeal to truth in the most capacious sense of the term. Rather, the destruction of the “listening heart,” the civilizing traditions and memories to which it appealed, and the denial of the availability of right and wrong to objective reason, all paved the way for the totalitarian negation of Western civilization. The totalitarian lie radicalized the subjectivism and relativism at the heart of liberal modernity. It did not so much re-enchant the world as empty it of all the resources of faith and reason. Comprehensive relativism, the denial of God and a natural order of things, and not some alleged moral absolutism, is at the source of the worst tragedies of the twentieth century. Pope Benedict never speaks in the name of “moral absolutism.” Rather, he points to the humanizing discernment made possible by conscience.

I have already noted that Pope Benedict is a foe of every form of fideism and religious fanaticism. Like St. Paul in the Epistle to the Romans, he appeals to the law that “is written on men’s hearts,” a law to which the conscience “bears witness.” (Romans: 2:14 f.). As Benedict says in the Bundestag address, Christianity does not propose “a revealed law to the State and society.” It respects the integrity of the political sphere and does not ask for revealed truth to become the explicit foundation of secular law. It does not completely conflate—or separate—the “things of God” and the “things of Caesar.” Rather, with the Stoics, “it has pointed to nature and reason as the true sources of law,” nature and reason mediated by our “listening hearts.” Pope Benedict does not claim that the German Basic Law of 1949 (or other modern affirmation of human rights) owes everything to Christianity but he does not understand how its claims made on behalf of human liberty and dignity can be justified without “Solomon’s listening heart, a reason that is open to the language of being.” That phrase beautifully articulates the difference between classical Christian reason and the positivist substitute for it.

The dogmatic separation of the “is” and the “ought” at the heart of modern philosophical discussions of ethics make nature simply “functional”, devoid of guidance for ethics and politics. It is an impersonal system of “cause” and “effect” with no relevance for ethics or common life. Norms are said to be rooted in “will” and thus pure arbitrariness (see Hans Kelsen who is referred to by Pope Benedict in the Bundestag address), and not reason and truth. Benedict protests against this reduction of ethics to the realm of will and subjectivity. He insists that there is an “ecology of man” that must be acknowledged by all those who care for truth and human dignity. “Man too has a nature that he must respect and that he cannot manipulate at will.” Contemporary Europeans have become ardent ecologists, as the Pope appreciatively notes, at the same time, they increasingly repudiate the natural moral limits inherent in the human condition. Crucially Benedict adds that “Man is not merely self-creating freedom” as the existentialists would claim. Benedict draws all the necessarily conclusions for a true moral ecology of human freedom and responsibility. Man “is intellect and will, but he is also nature, and his will is rightly ordered if he respects his nature, listens to it and accepts himself for who he is, as one who did not create himself.” The beginning of wisdom is to know men are not gods. The Pope insists: “In this way, and in no other, is true human freedom fulfilled.” Benedict’s quarrel is not with democracy per se but with its jettisoning of the ecology of freedom, rooted in conscience and “the listening heart,” that gives ample moral content to our freedom.

In discussing the true foundations of law, Benedict returns us to the Old West of Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome. This return is not carried out for the sake of rejecting modern liberty, but to reveal its salutary dialectical dependence on “Israel’s monotheism, the philosophical reason of the Greeks and Roman Law.” Europe did not begin with the Enlightenment, not to mention May 1968 (the starting point of what we can call “humanitarian” or “post-Western” democracy). The “inviolable dignity of every single person” and true criteria of law stand or fall with our recognition of the guiding light that is the “listening heart,” that moral and cognitive faculty that gives us “the capacity to discern between good and evil, and thus to establish true law, to serve justice and peace.”

As Benedict’s 1992 essay “Conscience and Truth” makes clear, Benedict sides with Cardinal Newman in rejecting any identification of conscience with subjectivism and relativism. The redoubtable Catholic convert deferred to conscience in all things, and saw in it the indispensable cornerstone of the Catholic faith. As Benedict writes, for Newman and the tradition on which he draws “conscience means the abolition of mere subjectivity when man’s intimate sphere is touched by the truth that comes from God.” A “true man of conscience,” such as St. Thomas More, “did not in the least regard conscience as the expression of his subjective tenacity or of an eccentric heroism.” Conscience is our portal to the natural moral law, and it is indeed written “in the hearts of men.” Subjective tenacity is what the Hungarian philosopher Aurel Kolnai called a “second-level good.” As such, it can be compatible with evil as well as good (the same can be said for the “authenticity” so valued by modern relativists).

Benedict also clarifies the Church’s teaching on our obligation to obey even an “erring conscience.” Conscience entails a “primal remembrance of the good and true,” an anamnesis that the Church and our civilized inheritance reinforces and sustains. Those ideological fanatics such as Hitler and Stalin who arrive at “perverse convictions” do so by “trampling down the protest made by the anamnesis of one’s true being.” Dulled to truth by ideological lies, they are guilty at a much deeper ontological level. Their perverse convictions are wholly separated from conscience, rightly understood.

Pope Benedict’s discussion of conscience and “the listening heart” is just one way in which his thought and work enlarges reason and reveals its “true greatness.” His reflections, at once theoretical and practical, theological and moral-political, can be fruitfully compared to the complementary witness of the anti-totalitarian dissidents of the East. Solzhenitsyn’s appeal to “live not by lies!” (and his concomitant insistence that “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being”) and Václav Havel’s reflections on “politics and conscience” point in the same broad direction. Solzhenitsyn’s and Havel’s admirable defiance of the Communist behemoth was inseparably a call for “living in truth.” That call did not cease to be relevant after the fall of European totalitarianism. Only by reconnecting truth and liberty, politics and conscience, can modern man free himself from what C.S. Lewis called “the poison of subjectivism.” By pursuing such a reconnection, we might take some sure-footed steps toward delivering on the promise of a liberty worthy of man.

Sources and Suggested Readings

These remarks were delivered at a colloquium “On Secularization: Reflections on the Relationship of Christianity, Culture, and the Politics of Liberal Democracies “ held in Paris on May 12-13, 2017.

I have drawn on the speeches in Liberating Logos: Pope Benedict XVI’s September Speeches, edited by Marc D. Guerra, Preface by James V. Schall (South Bend, Indiana: St. Augustine’s Press, 2014). I am indebted to Marc D. Guerra’s “Preface” for its emphasis on the theme of the excessive “self-limitation of modern reason” in Pope Benedict’s thought. The Bundestag address of September 222, 2011 can be found on pp. 39-48.

Pope Benedict’s superb 1992 reflection on “Conscience and Truth” can be found in Pope Benedict XVI, Values in a Time of Upheaval (New York: Crossroad Publishing, 2006), pp. 75-97. See the luminous discussion of Newman and Socrates as “Signposts to Conscience” on pp. 84-90.