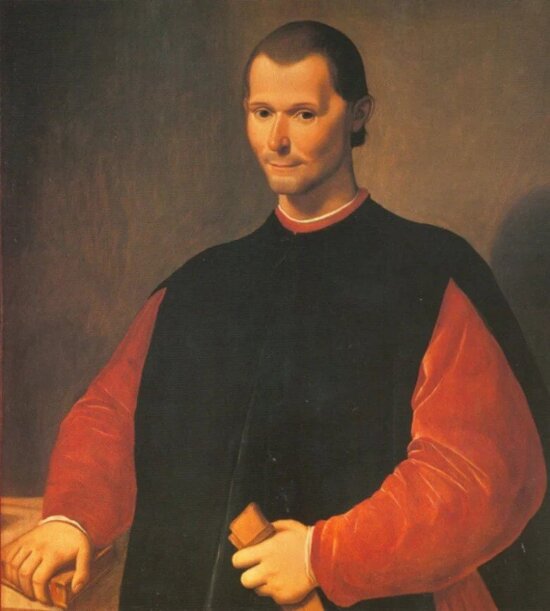

Machiavelli’s Restrained Violence

The Prince was written by Niccolo Machiavelli during the Renaissance as a guide to rulers. His advice is meant to allow rulers to govern and maintain their principality. The ruler of a regime must be prepared to vary his actions in accordance with the times. Therefore, he must be prepared to be just and unjust, merciful and cruel. Properly used, cruelty benefits the ruler and the regime by promoting long-term stability and the continued rule of the prince. However, there are difficulties in committing such violence. First, for cruelty to be well-used, it must be done only when necessary, all at once, and so far as possible to the benefit of the people. Secondly, the ruler must be able to change his nature and vary his actions as necessity demands. The advice Machiavelli provides lacks the concern of both ancient and Christian writers for justice. He is a pragmatist, concerned with attaining and keeping power in a polity. Machiavelli makes clear the rule of a prince is difficult. His mild call for moderation in the use of cruelty is often overlooked by readers of The Prince.

Machiavelli did not engage in a discussion of the best regime or the just regime, but how the regime sustains itself. Plato, Aristotle, and others had explored the best form of government: how it could be founded and how it would operate. While they acknowledged the need to respond to necessity, they situated their works within a moral framework. This moral framework would (should) influence how the ruler acted. Machiavelli wrote that it was his intention to write the truth in order to give effectual advice. He describes neither a perfect nor just regime and he is not concerned for the soul of the prince. His advice is not limited to current rulers; it is written for those who aspire to rule as well. This is understandable given what he says regarding man’s desire to acquire. He writes, “And truly it is a very natural and ordinary thing to desire to acquire, and always, when men do it who can, they will be praised or not blamed; but when they cannot, and wish to do it anyway, here lie the error and blame.”[1] Men desire riches and glory and are justified in attempting to attain the throne; whatever measures necessary to accomplish these goals are justified if they are successful. This was shocking advice. Harvey Mansfield writes, “Machiavelli in The Prince abandons the moral teachings of the classical and biblical traditions for a new conception of virtue as the willingness and ability to do whatever it takes to acquire and maintain what one has acquired.”[2]

While these principles are decidedly effective, they are morally reprehensible because they ignore man’s nature and telos. Machiavelli is unconcerned whether the soul of the prince is tarnished or if the citizens are virtuous. The concerns Machiavelli fixates on are the conquests of the ruler and the contentedness and acquiescence of the citizenry to his rule. The reason for this concern is the primacy of the polis for Machiavelli and the need for men to act to sustain it rather than blindly submitting to Fortuna. Therefore, men should act for their own advancement and glory in the light of necessity, not morals or mores. As necessity changes, so must the deeds of men.

The prince must act as necessity demands. The ruler of a polity faces many challenges that constantly shift and change. Machiavelli writes, “Hence it is necessary to a prince, if he wants to maintain himself, to learn to be able not to be good, and to use this and not use it according to necessity.”[3] The world is full of men who are not good and will not conduct themselves as such. It is more akin to Thomas Hobbes’ state of nature in which there is “continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”[4] The Prince is a case study in men who through vicious violence and callous cruelty rise to power.

The ruler who persists in living as if men were angels will soon find himself ruined; realpolitik requires the prince beware ambitious subordinates and prepare himself and his kingdom for foreign threats and internal disorder. In order to protect his power, his regime, and his life, the prince must respond as necessity dictates. Leo Paul de Alvarez writes in The Machiavellian Enterprise, “The concern of the prince must be to keep the state; nothing else is significant…The greater the demands of necessity, the greater the importance of the state and the political and the less that can be given to human excellence.”[5] Machiavelli prioritizes the power of the prince and his rule over the security of his soul. The prince must taint himself to preserve the state and maintain the benefits it provides-security, peace, and order. These things are necessary for the common men who make up the state. Therefore, to survive and benefit others as well as himself, the prince must learn not to be good, to trample upon accepted moral norms, the dictates of Christianity, and the commands of conscience. The prince must learn to use cruelty well.

Men often need to be cruel to attain power or maintain their rule. Cruelty may be good or bad depending on whether it is wisely or unwisely employed. According to Machiavelli, cruelty is permissible if it is well used, that is “done at a stroke, out of the necessity to secure oneself, and then not persisted in but are turned to as much utility for the subjects as one can.”[6] Proper use of cruelty dictates it be rarely used, done only out of necessity, and for the benefit of subjects so far as is possible. Poorly used cruelty continues and grows in its enormity rather than ceasing when necessity has passed. Those rulers who are unable to control their passions or exercise prudence frequently misuse cruelty. The misuse of cruelty is not only ineffectual in maintaining power; it also results in the ruler’s ruin. Two examples of well-administered cruelty are provided by Machiavelli in Chapter VII of The Prince: (1) the actions of Agathocles in seizing control of Syracuse and (2) those of Cesare Borgia in conquering the Romagna, restoring order through his servant Remirro de Orco, and letting vent the passions of the people in his brutal and violent execution of that obedient servant.

Agathocles is an excellent example of cruelty well used. A commoner by birth, he rose to achieve high rank, eventually becoming praetor of Syracuse through his virtues and martial prowess. Following man’s natural desire to acquire, Agathocles decides to become ruler and prince in his own right. Gathering the civic leaders and richest men of the city, he slaughters them without cause or provocation. Thereby, he is able to securely become ruler of the city and fight off threats to his power. Machiavelli thinks Agathocles is able to maintain his power because he knows what violence is needed and commits the heinous deeds necessary only once, refraining from repeating them. Violence allows him to gain the power he desires, while eliminating those who would oppose him. His later moderation keeps him from alienating the majority who care only for their property and their women.

While Agathocles is used as an example of well-used cruelty, Machiavelli thinks the actions of Cesare Borgia are more worthy of imitation. Machiavelli highly praises Cesare Borgia, the Duke Valentino, for his actions. Cesare conquers the Romagna, attempting to set himself up as ruler of this territory. The Romagna had been plagued by weak lords who had pillaged their subjects, leaving Romagna a lawless land. Good government requires strong rule. Cesare, therefore placed Remirro de Orco, “a cruel and ready man,”[7] in charge of the territory. He soon provides the order and peace the land lacks. Cesare, however, worries the excessive authority of de Orco might breed hatred and cause trouble for himself. While the strong-arm tactics achieve their end, a continuance of this policy would have likely caused discontent and tumults among the people. Therefore, Cesare does two things. First, he sets up a civil court to provide legal recourse to injustice. Secondly, he has Remirro de Orco seized, brutally sawn in half, and left in the public square. The people are both satisfied with the result and stupefied by the ferocity of the deed. While content with the justice provided, Cesare’s visible cruelty make the people keenly aware of the Duke’s power. Machiavelli deems the actions of Cesare Borgia proper and worthy of imitation.

Duke Valentino and Agathocles are two examples of Machiavelli’s idea of well-used cruelty. Cesare Borgia brings order and stability to a lawless region to increase his power. He does so through the violence and authority of Remirro de Orco, a servant he brutally murders when necessary to maintain his own power and placate the people. He recognizes what necessity requires and responds accordingly, not shying away from callous cruelty to achieve his goals.

Agathocles murders the leaders and wealthy members of a city that had promoted him to high rank despite his low birth. He is an excellent example of cruelty used but once in order to achieve the useful—the power and rule of a polity. After this initial act of cruelty, he refrains from such further heinous actions, choosing rather to secure his rule by courting the people’s favor through more benevolent measures. Although Machiavelli uses these men as examples of the proper use of cruelty, he distinguishes between the two. He assigns to Agathocles success in his endeavors and to Cesare Borgia glory.

Machiavelli does not unstintingly praise Aghathocles, but rather tempers his approval in a well-calibrated statement: “Yet one cannot call it virtue to kill one’s citizens, betray one’s friends, to be without faith, without mercy, without religion; these modes can enable one to acquire empire, but not glory.”[8] Agathocles’ cruelty secures success but not glory. Victoria Kahn writes, “Machiavelli wants us to understand that there is a difference between power, which Agathocles incontrovertibly did achieve, and the reputation for glorious deeds, which he did not.”[9] Kahn argues Machiavelli views virtue and vice as good in respect to how a leader uses them. Vice and virtue properly used enable one to respond to circumstances and achieve success. Glory is reserved for those who found, re-found, or expand the regime. Therefore, while criminal achievement is not wrong in itself, it cannot atone for sins committed in attaining success; it does not lead to the glory that Machiavelli extols throughout The Prince.[10] Agathocles is successful. He is an example of a man who uses cruelty well, yet he does not attain the glory of more eminent men. He doesn’t achieve the type of glory Machiavelli thinks the ruler of a regime desires, the glory of founding, re-founding, or expanding the regime. While cruelty is justified under Machiavelli’s criteria, the wise prince will reflect upon whether or not cruelty will bring him true glory or mere success.

According to Machiavelli the prince is justified in committing evil for three reasons: in the name of self-preservation, when cruel and evil deeds are effective in attaining power, and when such deeds maintain his power. He equates maintaining the prince’s position with maintaining the state. A powerful and effective ruler will be able to rule and lead the people, effectively protecting the nation from envious foreigners while maintaining internal order. Good government is only possible when the state is not weak and divided through weak, inefficient rulers. Cruelty well-used should to some extent benefit the people. This criterion acts as a check upon the deeds the ruler may commit. Cruel actions must not only advance the power of the ruler, they should also be useful to the people. The actions of Cesare Borgia, while violent and cruel, bring order to a lawless land. This benefits the people, allowing them to more securely enjoy the fruit of their liberty. It also increases the power of the Duke. Duke Valentino’s actions, while cruel, are certainly more merciful than the unmerciful inaction of leaders who hesitate to do what the times require. In chapter XVII of The Prince, Machiavelli notes that the Florentines hesitate to earn a name for cruelty. Their inaction results in the destruction of an entire city, Pistoia.[11] Machiavelli reasons that if the preservation of the polis is the primary goal, and if in preserving the polis a ruler maintains his power and prestige, then barbarous deeds are necessary and justified in accomplishing these goals. Machiavelli has a hierarchy of ends. Within that hierarchy, the preservation of the regime is highest.

Cruelty may make effective virtues that would otherwise fail to come to fruition. Machiavelli uses the example of Hannibal to emphasize the point that cruelty may be required for the ruler or the aspirant to rule to achieve his ends. He writes, “Indeed, without cruelty the virtues of Hannibal would have had no effect; cruelty is what makes virtue or truth and goodness effectual.”[12] Hannibal had many positive virtues that were useful to him as a commander. However, he would never have been able to achieve his military victories without the strength and will to commit barbarous deeds. These savage deeds held a disparate army together and kept it loyal though good and ill fortune. While cruelty well used has benefits in securing the prince in his reign and enabling the aspirant to seize power, it also requires prudence and adaptability.

Machiavelli advises rulers to use cruelty well and respond to necessity. This requires prudence as well as the ability to change habits. The wise prince must be able to be both good and bad, cruel and merciful, just and unjust. Knowing when to embrace these two extremes requires prudence. Prudence is knowing the right action to take in a particular circumstance in order to achieve the end. The end has traditionally been a moral end—virtue. In contradistinction, virtue for Machiavelli is the acquisition of power, riches, and glory via the preservation of the state. Cruelty must be used prudentially. First, the prince must know what cruelty is required, when it is required, and when to do it all at once. Second, he must be able to refrain from repeating the behavior that brought him his original success. Excessive cruelty results only in the ruin of those who practice it. Third, he must be able to adjust his behavior as necessity requires. If the times allow, he should follow the good; if not, he must practice what evil the times command. Tragically man, because of his fixed nature, is rarely able to exercise the reason and foresight required to determine when to adjust his actions in the face of necessity. Machiavelli implies that the predisposition of men to act in certain ways—especially when this has brought past success—is largely fixed. He writes, “Nor may a man be found, so prudent as to know how to accommodate himself to this, whether because he cannot deviate from what nature inclines him to or also because, when one has always flourished by walking on one path, he cannot be persuaded to depart from it.”[13]

Men tend to repeatedly respond to a challenge or crises in the same manner, especially when those responses have garnered success. This innate tendency (nature) limits adjusting one’s response to the situation. The wise prince recognizes and overcomes this tendency. He prudently responds according to the times and circumstances in which he finds himself.

Machiavelli provides advice that initially seems exceedingly brutal. Yet closer examination of Machiavelli’s proposals reveals moderation of cruelty. Evil should be committed only when the times require it but if possible the ruler should be good. Cruelty well-used has a three-fold standard: it must done at once; out of necessity to secure power; and as much for the good of the people as possible. These standards should moderate the behavior of the prince and prevent the excessive cruelties that result in the ruin of the prince.

The best prince operates under the laws and earns glory through founding, re-founding, or expanding the state. The deeds of the prince are judged not for their moral qualities but for their ability to achieve the prince’s power and the preservation of the regime. This places high demands upon the abilities of the ruler. He must have prudence to know when to be evil and when to be good. Secondly, the prince must be able to adjust his behavior to fit the times. What brought him success originally may not be what is required to preserve his throne and maintain the state. Machiavelli indicates that it is difficult for men to adjust their actions such as Agathocles did, committing cruelty to achieve power and then acting in a manner that benefited the people, preserved the state, and maintained his power.

The Machiavellian prince is not overly concerned with his soul but with maintaining his throne and his state. He may commit heinous deeds but he must do so in a moderate manner, on rare occasions and when forced by necessity, exercising prudence and adjusting actions accordingly. The result is an amoral prince presiding over a regime that will generally benefit the people by providing foreign defense, internal security, and reward virtue among the people. Even with the lowered standards of politics required by Machiavelli, this is a rare regime and many who have tried to attain it have strayed badly from the whole of his advice.

References

Alvarez, Leo Paul de. The Machiavellian Enterprise: A Commentary on The Prince. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1999.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan with selected variants from the Latin edition of 1688. Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Edwin Curley. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1994.

Kahn, Victoria. “Revisiting Agathocles.” Review of Politics 75, no. 4, (Fall 2013): 557-572.

Machiavelli, Niccolo. Discourses on Livy. Translated by Harvey C. Mansfield and Nathan Tarcov. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

______. The Prince. Translated with an Introduction by Harvey C. Mansfield. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

[1] Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince, trans. with an Introduction Harvey C. Mansfield (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 14-15.

[2] Niccolo Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy, trans. Harvey C. Mansfield and Nathan Tarcov (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), xxi.

[3] Machiavelli, The Prince, 61.

[4] Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan with selected variants from the Latin edition of 1688 ed. with an Introduction and Notes Edwin Curley (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1994), 76.

[5] Leo Paul de Alvarez, The Machiavellian Enterprise: A Commentary on The Prince (DeKalb: Northen Illinois University Press, 1999), 77.

[6] Machiavelli, The Prince, 37-38.

[7] Ibid., 29.

[8] Ibid., 35.

[9] Victoria Kahn, “Revisiting Agathocles,” Review of Politics 75, no. 4, (Fall 2013): 568.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Machiavelli, The Prince, 65.

[12] Ibid., 67.

[13] Ibid., 100.