Monism vs the Trinity

There seems to be some universal tendency to want to find the single underlying thing or principle that unites and explains everything. The person regarded as the first known Western philosopher, Thales, began this with “all is water.” Materialists claim the single unifying thing is matter, some theists claim it is God or Spirit, while Buddhists might say Emptiness, or Pure Awareness. It seems strange that people with such differing beliefs should have this shared intuition. It can seem as though monism (one-ism) must have some basis in fact if such very different views come to the same conclusion, even if the actual imagined make-up of “the one” differs so wildly.

Common alternatives to monism are dualism – there are two things – usually body (all physical reality) and mind, and the ten thousand things of Buddhism. However, the latter exist only as the traditional name for the indefinite number of individual objects that disappear in Pure Awareness once the object/subject distinction is overcome.

Buddhism acknowledges various stages on the route to monism. In meditation, the mind is the subject that observes the body as object. Then the mind and ego are observed by the soul, where mind is object, and soul is subject. Finally, the subject/object distinction is overcome in the experience of Spirit, nothingness (no-thing-ness), resting in nondual reality; pure awareness. Consciousness is then considered unitary because without subjects and objects, thoughts and feelings, and individual bodily sensations, one person’s consciousness is essentially identical to another’s.

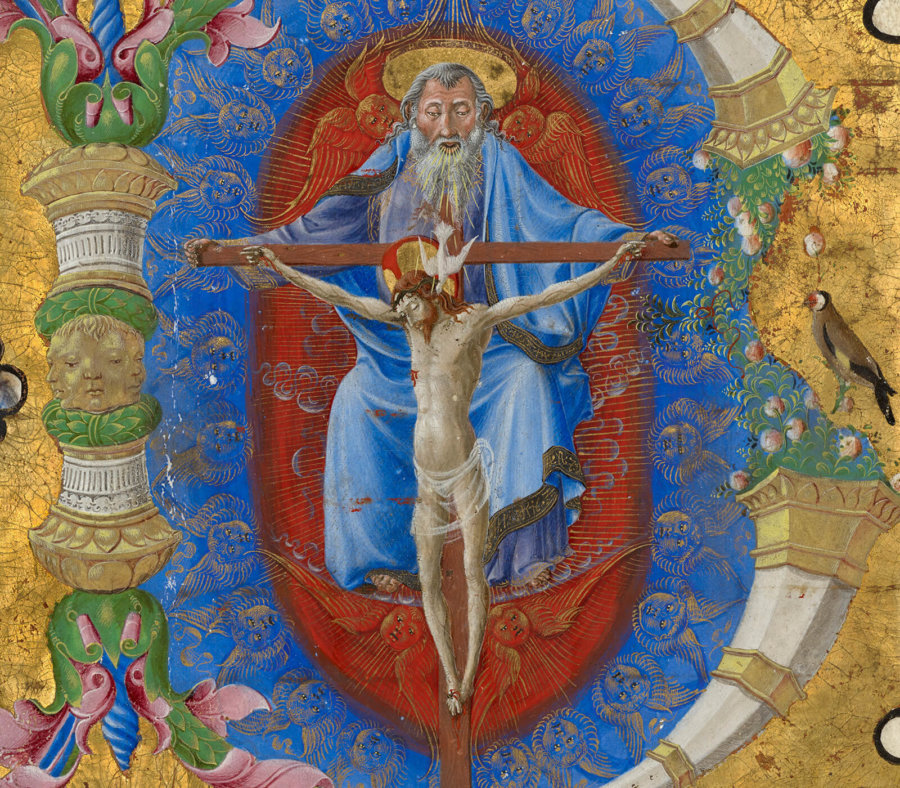

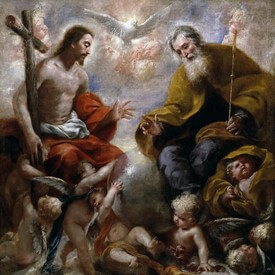

Christianity rejects monism in favor of the mystery of the Trinity. In Paul Johnson’s A History of Christianity, he claims that Islam’s success was partly the result of its resolute monism, which, as has been noted, attracts many people, and many types of people, in contrast to the “problem” of the Trinity.[1] Another alternative to monism is the traditional idea of the one and the many; the One being the Godhead, as in Plotinus’ renaming of Plato’s Form of the Good. In the theology of the one and the many, the one produces the many and has compassion for them, agape, and the many turn around and search for their maker; eros; upward directed love. The phrase does have some overtones of what René Girard calls the false sacred – where a scapegoat victim is divinized as the godlike cause of social chaos, and later after his immolation, as the equally seraphic, beneficent bringer of peace, supposedly sacrificing himself for the benefit of the group. The scapegoat dynamic is unanimity minus one. The many murder the one and then worship him as a god. However, if there really is a God, then “the one and the many” seems like an appropriate description of the Creator and the created. The Old Testament God was not yet thought of as triune, Plato’s Form of the Good was unitary, and yet Christians admired his philosophy, and Plotinus’ truly admirable life centered around mystical experiences of God as the One. Plotinus, following Plato, had his “Three Hypostases,” one of which is Nous, the level where the Forms exist, that is sometimes described as the mind of God. So, there is a kind of semi-trinitarianism in Plotinus too. The key thing about the one and the many is that it is not metaphysically monistic. The many retain a distinct existence. And trinitarianism dispels any lingering sacrificial overtones of “the one.”

It is true that in praying to God, it would seem that most Christians would pray to just one aspect of God or another – God the Father, or to Jesus. There is a communal prayer to the Holy Spirit alone; “Come Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of your faithful, and kindle in them the fire of your love,” but that is extremely rare. In contemplative, non-petitionary prayer, it seems unlikely that many people are trying to listen to a Trinity.

And then Christian mystics have had a strong tendency towards monism. Ken Wilber describes the path of all mystics of every description as the shaman, becoming one with nature – but not God; the saint, who comes face to face with God, the sage who becomes one with God, and the siddha who knows himself to be God and Creation in nondual reality. But Wilber is careful to warn of the inadequacy of monism and promotes Arthur Koestler’s notion of holons to avoid it. Holons have a whole/part structure. They are whole unto themselves, and they are part of a larger reality. Holons do not dissolve into oneness.

Monism has horrible political implications – the State is all important and the prime reality and its citizens are disposable nothings with no intrinsic worth in service of the “greater good.” Likewise, religious monism obliterates the importance of individuals in a similar manner. Gnosticism, in competition with Christianity from the very beginning, has as its final stage an individual’s divine spark rejoining the One and ceasing to have any independent existence. Though this fate is reserved for the elect, those with esoteric gnosis (knowledge), the ideal is the elimination of the many, the created; though part of the fun of Gnosticism is to think oneself to be one of the enlightened few, rather than part of the many. Gnostic monism is nihilistic to the core. All beings are aspirationally to vanish into some great nonbeing. The striking down, the obliteration, of the many returns us to sacrifice. The One, as the sacrificial victim, gets its revenge on the mob, the many, by subsuming them within itself and extinguishing them. Alternatively, the many become the one by forming a mob, which then eliminates the one remaining outside itself, and also the self-direction of its members.

Paul’s letter to the Corinthians where he says “You are the body of Christ. Each one of you is part of it” contains elements emphasizing that each part; ear, eye, hand, foot, has its own irreplaceable value, and that unhonored parts of the body are as valuable in God’s eyes as other parts. The head cannot say to the feet that it does not need them, and if one part of the body is suffering, then the whole suffers. All are baptized into one body, whether Jew, Gentile, slave or free man. Paul’s intent is to minimize resentment, and promote fellow-feeling. The downside to the metaphor is that though each part is necessary, its value is extrinsic – its service to the body. A foot is nothing without the body and is there to serve the body and nothing else, as opposed, for instance, to an art museum where each work of art contributes to the greater whole, but is also uniquely valuable in its own right. The body of Christ, and its parts, is not monistic; the parts remain parts, with their own functions, but bodies have their own destiny and purpose that overrides the parts. An important element of God’s plan is that we determine our own plan, as adult children reveal their life decisions to their parents. The body metaphor has the limitation that it cannot connote the existentially necessary voluntarism and self-direction of the parts.

Religious monism typically sets itself up in competition with scientific monism – but like all participants in an agon,[2] they come to resemble each other. Both kinds of monism seek a thorough-going super explanation of everything. Religious monists rid reality of the Trinity, an insuperable obstacle to complete rationalistic explanation, and thus remove much that is mysterious and paradoxical. There is a tendency towards spiritual determinism in this move. If everything is God then it seems that there is no escape from God’s plan. Presumably, God’s right hand knows what His left is doing. If God’s actual plan is for spiritually independent creatures to create their own plans, then those creatures will need some kind of separate identity of their own, and to partake in the Ungrund – meonic Freedom that pre-exists God the Father. A principle of Freedom that permits each of us to create our own destiny, unpredictable to ourselves or to God.

Logical positivism claims that any nouns not based on verified scientific entities not only do not exist, but are entirely meaningless. The resulting notion of scientism contends that only scientific truths are veridical. Only science provides a pathway to truth. Their main target is God and religion. God not only does not exist, but it is meaningless to refer to him, in their view.

But there is a strain of theism represented by Theosophy and Spiritualism, that applies science to the question of the existence of God and religion. Frederick Myers started the Society for Psychical Research that sought to study paranormal phenomena scientifically, including mediumship that has obvious religious implications. Some of the very same people who protest against the narrow-minded attitude of positivism are happy to extend the scientific method into religious matters. They will try to prove that an afterlife exists, that near-death experiences are legitimate, and that God is real. By doing this, they have not overcome scientism, they have succumbed to it. They hope to use the tool of science to convince people devoted to science and materialism that they are wrong, which almost never works. Such people are strangely fascinated and concerned with the question; of what are we made? Are we really made of matter? Or is matter really illusory, perhaps a mind-dependent phenomenon as some interpretations of quantum mechanics suggest? Somehow, they imagine that proving that material reality is really spiritual reality will be very helpful and illuminating. They are not so very different from the current vogue for thinking that we live in a computer simulation in which case the underlying reality will be a bunch of zeroes and ones. Does that count as monism or dualism, one wonders? And, what actually changes about life as we know it, if this is a simulation? We are born, grow old, and die, and need to decide how best to spend the resulting interval.

Spiritual monism deems physical reality an illusion, just like some Buddhists, and asserts the primacy and unity of spirit. But, who cares what someone is made of? If a creature like the android Data from Star Trek Next Generation existed, then he deserves to be accorded personhood whether he is made from circuits, or flesh and blood. Data exhibits consciousness and feelings, despite all his claims not to possess the latter. It seems safe to say that any conscious being has a soul.

The traditional conception is that people have a physical body and an eternal soul that lives on when the body dies. Regardless of whether physical reality is actually spiritual reality, the body still dies. The only question of religious and thus philosophical importance is, is there something more than the body? In heaven, we live on with an incorruptible spiritual body, instead of a physical body. The physical body is subject to death and decay. Proving that material reality is a projection of spiritual reality does not change any of these facts in any significant way. It is a red herring and irrelevancy. The only advantage would seem to be that if quantum mechanics somehow implies physical reality is really spiritual reality then religion and faith get the blessing of science. Frankly, if anybody is handing out blessings, it is for the religious to bless science.

When asked which is the most important commandment, Jesus replies: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your mind, and with all your soul. And love your neighbor as yourself. There is no commandment greater than these.” At the heart of both central commandments is love. We are not commanded to figure out the nature of reality, but to love God and one another. 1 Corinthians 13 reiterates the importance of love. Without love, knowledge, and faith, and prophecy, and all the rest, are worthless – annoying clanging cymbals and nothing more. Love is an internal feeling associated with subjectivity – the subject. It cannot be seen, only felt or inferred. The thing of central importance to Christianity is invisible and not subject to scientific investigation of any kind. It is not Jesus’ visage that is important, but what is going on invisibly inside him; what he is feeling and how those feelings make him act. The spiritual is connected with interiors. Heaven and earth might emanate from Spirit but they are not spiritual per se. They are exteriors. It is love that is important, not stuff; not things, not bodies, not heavenly visions, not reports of the afterlife, not mediums communicating with the dead, not Beethoven dictating new compositions to psychics.

If it turns out that material reality is just how we have traditionally thought of it, what bearing does that have on whether we should love God and love our neighbor as ourselves? If my neighbor is physical, but has an eternal soul, I shall love him. If my neighbor is a projection of spiritual reality and his body is really a mental phenomenon of some kind, how should my love for him change? His spiritually generated “physical” body will still grow old and die, or get a disease or have an accident and die young, and then he will need an actual spiritual body that does not die. It is true that if my neighbor is not made in the image of God, if he has neither an immortal soul nor is he a projection from a divine reality, and he is only an unlovely collection of atoms arranged through random mutation and natural selection – something not even properly informed biologists think any longer – then it is impossible to say why I should love him. I do not love other happenstance pieces of junk.

If God is the Creator, and he creates the world, we should love his creation as we love Him, whether his creation is atoms and molecules, or whether it is really mental stuff of some kind. The stuff part is not what is important. Either way, a creator is indicated. Physical reality, even if it is just as we normally think it is, points to spiritual reality, just as works of art, and musical compositions, point to the spiritual and creative interiors of their creators. All human creations are symbolic. They point to the interior lives of their makers. And we humans point to the maker that is God. He provides our connection to freedom, infinity, and the Ungrund, and thus creativity and imagination – and he gives us intuitions of his existence.

Scientistic theists want to diminish our freedom by trying to offer scientific evidence of God’s existence. They never ever seem to talk of hope and faith, and that is fundamentally unchristian.

It is possible for mystics to have genuine experiences of temporarily merging with God, of being God, of going beyond any division between Emptiness and form, without this indicating that this can or should form an adequate theology or metaphysics. The fact that we can temporarily unite with God, and it is always experientially momentary, does not mean that we do not exist or have no separate reality from him. It might be true that it is in God that we live and move and have our being, but that does not imply monism. Maybe we are made of the same spiritual stuff as God. Maybe God is some kind of all pervasive field of which we are part. Who cares? We are to love God and our neighbors and we cannot do this if we do not exist and our neighbors do not exist. In fact, it is pointless to command us to do anything if we do not exist. God might provide the ground of our being, but, if so, it is not a ground that annihilates us. There might be a continuity of substance (not in the Aristotelian sense) between God and us, but our interiors are what are important. If monism is true, and we have no real existence, then God is not the Creator, for his Creation does not exist. Or was God only capable of creating an illusion, and why would he do that? God is just some hack magician?

Love requires division. The lover and the beloved. But it is a division that is overcome in voluntary connection. It is two hearts joined as one. It is not one heart that notices it is one heart. Getting rid of metaphysical divisions between spirit and matter does not provide the basis for love. A voluntary communion with God and neighbor provides that connection and it is the only connection that means anything. Being connected physically, or through spiritual monism, means nothing. If love just means becoming aware of a connection that already exists, then this connection is not truly voluntary, and thus is worthless. It is love with a gun to your head.

Ken Wilber distinguishes between Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism. Theravada Buddhism is an earlier version that recognizes that Form is Emptiness. Form is not ultimate reality, but stems from the Godhead, as a Christian might say. This kind of thinking is congenial to monism. Form is an illusion. Attachment to Form, to objects, to people, creates desire and desire is suffering. Suffering exists in multiplicity and attachment to the multitudinous. Enlightenment involves seeing beyond to the No-thing. Wilber thinks that Buddha only got to this stage himself. Mahayana Buddhism, exemplified by Tibetan and Zen Buddhism, takes that one step further and sees that Emptiness is Form. The Godhead, the Nothing, gives rise to Creation; to the many; to the ten thousand things, and as the creation of God they share in his divinity.

In Christian Trinitarianism, we are to love God and our neighbor, our fellow creature. We are not here to be re-merged with the Father. The monist, of a certain sort, claims that there is just one of us and we should love our neighbor because our neighbor is really ourselves, and we are God. Help me recognize that I am not me, I am Thee. Christ’s teaching, on the other hand, says to love God and our neighbor; God and his creatures. The Trinitarian doctrine rejects the monist, Gnostic, and sacrificial impulse; it says my neighbor is not me; God is not one; a child is not his parents, but has his own existence, his own destiny, and his own life. His wishes are not the parents’ wishes, and the parent loves the child. You are not me. Let us join together in love.

Notes

[1] p. 242, Paul Johnson, A History of Christianity.

[2] Competition, and related to “agony.”