Paris Without End

When I was a young girl, I wanted to be a great lover or a famous saint. Fortunately, once I was a bit older, my aims became somewhat more nuanced. I wanted to be conscious of the purposes behind my choices, rather than letting them guide me unawares. I wanted also to figure out what gave others their motives to act and feel as they did. It was a point of honor not to profess views if I was not prepared to put them to the test of living them. Also to encounter new experiences unencumbered by rigid preconceptions.

Cynicism was a rigid filter I declined to wear. It was insincere, I thought. Cynics, I felt sure, expressed disappointment. To me it seemed more honest to honor one’s original hope and make a second or third attempt to realize it. Better to remember how the hope got thwarted and try not to make the same mistake twice!

Of course I knew that I would meet life already clothed in an “identity” – not as an observer safely above the battle. I was a New York Jewish girl, born and raised in Manhattan, where I’d gone to high school and college, and the child of interesting parents. I was now away from home for the first time, in Paris on a Fulbright grant.

None of this seemed to me a limitation. There was the Holocaust, of course, at the horizon of Jewish experience. My parents had done rescue work while it was going on. It was an intimate fact, almost a memory. It meant that the facts of moral life, the facts of history, couldn’t be glossed over. I was obliged to seek the truth of whatever situation I found myself in. Life was not a game. Success was not the goal. Real life was serious.

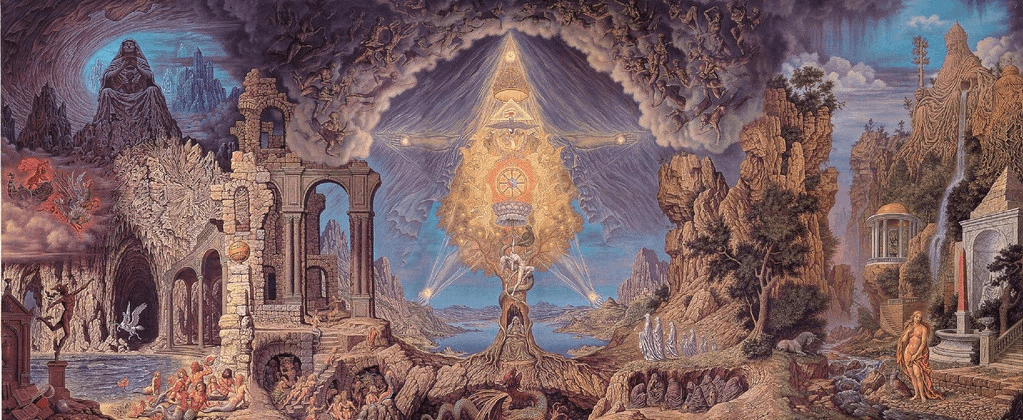

Did I think there was a God? Certainly I was no atheist. I knew that sanctity was a possible goal in people’s search for a good life. About wickedness my notions were more vague and abstract. For me, God was at least the Witness and Backup for a hopeful approach to experience that allowed one to look events and feelings in the face without trying to make them other than they were.

What about God and the Jews? What had happened in that relationship? Those questions seemed so embedded in the human story, so perennial and unresolved, that I felt no urgency about finding my way on that terrain. It was simply there, the question of God and the Jews – a big part of the topography of the world. Of anti-semitism, I had little or no personal experience.

I did feel obliged, as a Jewish girl who was not stupid, to situate my life on the larger map of human striving – in a world that was wide, not narrow. I wanted to know where I was, and not just in the realm of private and personal options. Instinctively, I sought to get my bearings and location in human history itself. It wasn’t a matter of ambition to “make history” or even to “make a difference” in history. I just wanted to know how to find me in the bigger story.

What did that mean, concretely?

If, for instance, a historian discovers a young girl’s cache of letters and the writer turns out an adherent of the Cathari movement in eleventh-century southern France, the historian’s introduction to the published edition will take for granted that the narrative is not merely personal. Her letters would also tell the story of a Cathar, who will suffer the consequences of decisions made in the Vatican to suppress that sect. Her thoughts, feelings, hopes and ordeal will thus be locatable in the history of the world.

That place in the story was what I was trying to find for my own early life, as I went along. It motivated me.

Was I fearful? Did I anticipate tragedy, or great suffering, at this moment of setting forth? No. I was filled with desire and thought I was ready for anything.

Like the Biblical prototypes, who were not above the battle, I too felt impelled to look for the Absolute in the context where life had placed me. Accordingly, I felt a responsibility to penetrate to the very heart of Paris: to know it so thoroughly that its place in my search would be forever established and exhausted. I would never need to know it more or better. I would know it, and all that it meant!

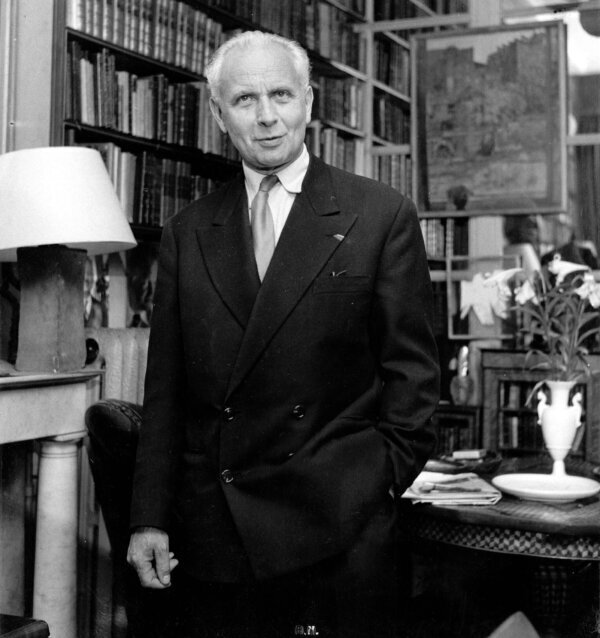

Among the young people on Fulbright grants who would turn out to be my friends, the American effort would be to maintain integrity. Our humanism was unencumbered by the unforgiving, Parisian, cosmetic attention to life’s carnal details that converted American existence in that city into a project of ironic and half-doomed resistance. Of that resistance project, my friend John Armstrong was, whenever anyone gave him the time, the natural leader.

“Whatever you do in this life will be your marker,” John said to me one time. “That will be your epitaph, your boundary stone. Every act, no matter how small, tells what you were, and that’s all anyone will be able to commemorate.

“Abigail, you may say you believe in immortality, but you have no way of backing that up. The fact is” – he looked my way as if calling the class to order – “that this present life is all you have. And you really know it.”

With an admonitory forefinger, John addressed his unseen, leaderless legions. “The Greeks, Homer, understood how things work. Up in the sky, he puts the gods. They seem to be racing around in their great stage machines. But they don’t exist. The only real part is the men on the ground, playing for the only stakes there are. The characters in Homer all know it. And that’s what they have to tell us.”

I took in this image. I was in Paris, after all, to study The Concept of Man in Aesthetic Experience. I had to study that because I’d never known how to dispute an image. Except with another image. Which left it that nobody won, but (as I fondly thought) nobody lost either. We all stayed in the game.

“John,” I asked, “when you die and get inside the pearly gates and find out there’s a whole next life going on, how will you feel? Very mad?”

A breath that he let out shone like a desert mirage in front of us both for a suspended few seconds. “Yeah,” he gasped, laughing at himself at last. “I guess I would be.”

By this time, I’d met a Greek communist philosophy student who framed life differently. For him, it was not about the importance of rectitude in the face of life’s brevity and hope’s futility. He had lived through the German Occupation of Greece. “They were gathering corpses from the streets of Athens,” he told me.

Under the Occupation of Paris, as the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty described it, one discovered that one had never lived in a realm of universal values. Rather one had lived in a space that was socially constructed, an artifact that the Occupiers had demolished, replacing it with a different artifact. The True, the Good, and the Beautiful were not eternal ideals but “contingent,” and therefore – the existentialists were quick to draw the inference – “absurd” in the sense of ultimately groundless.

For the Marxists, any rhetoric that invoked values as fixed realities must be “false consciousness,” masking something grittier: mere power. The communist wager was that power rested on an economic substructure that they could change, if first they set aside moral rules and social precedents.

In sum, the war and its defeats promoted a dark view of human existence. The images evoked by that dark view seemed more forceful, even, than the arguments. In the cafes, the young people wore black turtle-neck sweaters, smoked Gauloises and looked as if you couldn’t surprise them. All this was part and parcel of social Paris, which was tremendously influenced by the plane of ideas and danced attendance on whoever peopled that plane. Costume and all the erotic rhythms were played out in accordance with the ideas. To be a communist was masculine.

The couples one passed on the street were not inventing their interlocking dance. It was highly aestheticized, sure of its rhythm and – since it exempted itself from the flow of time – sure of its self-terminating character as well. Tristan and Iseult still appeared to model the erotic situation for the French. That proto-gnostic medieval pair had died young and thus preserved in amber their moment. Lucky lovers! Their real-life modern successors took for granted that they would outlive their moment. French popular songs of the day were full of regrets – for the singer’s years of erotic eligibility – lost and, by definition, irrecoverable.

Among my American women friends, all this was the subject of endless, intense discussion. We didn’t, of course, agree with this French idea of love: self-enclosed, outside of time, but also threatened at every moment by time and change. But we could not be unaffected by it.

For the fact was that we none of us had any margin as women. It was not a question of “standing” or “status,” as the new-minted feminists would begin to describe the problem a few years hence. It was a question of room – room to fail in, to retreat and turn again and beat some other path.

We felt, and wanted to attract, an idealizing ardor. But we were relying on what the Marxists might have termed the “substructure” of youth. It was our youth – understood as the power to attract — that supported us and all our professed fine values. Meanwhile, at any time, that substructure could be undermined.

When and as that happened, we and our fine values would become abstract. That was the worst thing that could happen to a woman: to profess values not attached to anything that was in fact valued. So the erotic details of life that the French forced on our notice were, inevitably, extremely preoccupying. This loss of femininity, the loss of womanly value, was an intense preoccupation with us. We discussed preventive measures, containment measures, concealment and cosmetic measures tirelessly.

What about the life of the mind? I was, after all, also embarked on that life. Could I not transcend the female predicament by withdrawing upward into the life of the mind? Aren’t the ideas, as Plato said, eternal? Don’t they transcend time and space and all the conditions of empirical embodiment?

Although I loved the life of the mind, it was not for me a self-sufficient objective. What I was interested in primarily was the truth about life, not the exercise of the mental faculties. For me, the truth about life was to be worked out between human beings and the God who participates in history in the settings that are actual and concrete, not imaginary settings.

The big question for us was how to endow our feminine existence with ineradicable value … and how to endow our values with feminine existence.

In principle, a way could have been found to reconceive the feminine and the philosophic life so that they might be made mutually inclusive. On paper, a dialectician could have worked out the synthesis. But I wasn’t living on paper. None of us is. Our ideas have to stand the test of our lives.

This excerpt is drawn from Confessions of a Young Philosopher, forthcoming.