Plato’s Crito and the Crisis of Sovereignty

The common reading of the Crito asserts that the dialogue examines the nature of just and unjust laws with contingent concerns for how a person should respond to the laws they find themselves subject to. Yet the heart of the dialogue, the discourse on the Laws, concerns itself with the relationship of the person (Socrates) to the sovereign nature of law in political life. More precisely, through the conversations between Crito and Socrates and Socrates’ imagined discourse with the Laws the dialogue deals with an examination of the nature of life and sovereignty which are intertwined with law, community, and the human person. The trial of Socrates, therefore, is also the trial to determine where sovereign power lay: the state or the person. This is the fundamental question that Plato examines in the dialogue.

Greek philosophy held a distinction between bios and zoē; between fulfilled life and bare life.[1] As Giorgio Agamben aptly summarized, “The Greeks had no single word to express what we mean by the word ‘life.’”[2] The differentiation between fulfilled life and bare life in the realm of the political is visible from Plato’s most famous student, Aristotle, who wrote that the emergence of the state comes from the “bare needs of life . . . [whereby] man, when perfected, is the best of animals, but when separated from law and justice, he is the worst of all.”[3]

Humanity’s perfection, for Aristotle, emanated from humanity’s political (or social) nature which leads to the formation of political community and fulfilled life therein consummated through arête and phronesis. Indeed, arête is impossible without political life in Aristotle’s political thought. Fulfilled life stands over and against unqualified bare life, with bios politikos relating to the good life compelled by humanity’s political animus and zoē being something miserable and unsettling. Bare life, then, is the embodiment of an outcast life without a home, a family, or a polis.

Despite the prominence of the bios-zoē distinction in Aristotle, the same distinction is also visible in Plato’s corpus; as is the concern over the nature of sovereignty and how sovereignty fits into the bios-zoē distinction. Subservience to law is a theme explored in many of Plato’s dialogues, the most explicit in my mind being found in the Euthyphro, the Republic, and the Laws. But in the Crito this theme of subservience to the law illuminates the bios-zoē distinction more manifestly than the other dialogues.

When conversing with Crito, Socrates informs him that he has had a satisfied life being a faithful member of the Athenian community.[4] Thus, it was in Athens—as a citizen and member of that political community—that Socrates consummated his calling for a fulfilled life. Socrates was satisfied with his life. This is what he states to Crito in the prison cell. In being satisfied with his life, Socrates had consummated the good life which political life is established to provide. But in the dialogue between Socrates and Crito, and between Socrates and the Laws, a paradox emerges: Socrates’ fulfilled life also reduced him to the state of bare life. Does fulfilled life in the political community necessarily reduce one to bare life as is evidenced by Socrates’ condition in the dialogue?

It is this paradoxical question, which straddles the interstices of life and sovereignty, which Plato is principally concerned with examining in the dialogue. The concern for which Plato places the question of life and sovereignty, and their place in the plane of bios politikos, continues Plato’s longstanding and running question of what kind of city do people find themselves living in. That was the question foundational to the Republic. And that is the question at the heart of most of his dialogues whether we readily recognize it or not.

Sovereign Power

The traditional view of sovereignty meant absolute control over life. It was marked by the power to decide who lives and who dies. Carl Schmitt aptly described the sovereign as “he who decides on the exception.”[5] In other words, the sovereign was the one who decides on the exception of who to include as a member of the political community, and have the space for fulfilled living, and who was to be marked as the outsider and subsequently be reduced to bare life by the act of exclusion. Sovereignty, then, is marked by this power of inclusion-exclusion into the political power in which humans occupy a middle-ground, a literal no-man’s land, by which they are marked as members inside the law or as animals outside the law.

Since the fulfillment of life is tied to the fulfilled life in political community because humans are political animals, the principle of sovereignty resting on the exception (in the form of exclusion) still entails control over living and dying and embodies the mark of bios and zoē. For the person admitted to the political community has life while the person excluded and marked for bare life is that “worst of [animal].” To be exiled from the political community is to be marked with the sign of bare life and, therefore, death.

Schmitt applied the definition of sovereignty to extend to “any emergency decree of state of siege.”[6] That is, it is in a state of emergency (a “state of siege”) when sovereignty becomes crystallized and most potently manifested. Only when the life of the political community is threatened, under that state of siege, does sovereignty forcibly manifest and wield its power against whatever threatens it (real or imagined) in the Schmittian account. The implication is that sovereignty is about life (through power) at all costs—to the point that sovereignty will take away life in order to preserve its own life. In this action sovereign power is displayed in this ability to control, or take, life. This is what marks the state of exception, “The exception, which is not codified in the existing legal order, can at best be characterized as a case of extreme peril, a danger to the existence of the state or the like.”[7]

Agamben also described the state of exception, in which sovereignty is coercively displayed, as the “no-man’s land between public law and political fact, and between juridical order and political life.”[8] Furthermore, Agamben noted the difficulty of understanding the state of exception due to its use of militaristic and wartime language alongside warlike imagery.[9] But if war is the struggle for life, rather than peace, then the state of exception—if there is life, for any life can be a potential threat to the existence of the political order—paradoxically also exists for the purpose of fulfilled life under the structural fabric of the state. Since the agon is fundamental to life, Agamben’s criticism of Schmitt is that Schmitt is too benign (or naïve) in seeing sovereignty only displayed in moments of siege (the state of exception). The siege, the state of exception, is always ongoing as long as one lives. The state of siege is the existential reality that life embodies. Therefore, the state of exception is in continuous existence and expands itself until there is an elimination of the no-man’s land which is the absorption of the space between the state and the person which makes civil society, and leisure society, possible. The elimination of that no-man’s land must be achieved for the state to feel existentially secure.

Insofar that life begins at the margins, birth, life is first characterized by powerlessness. One is dependent upon others for their nurturing, survival, and growth to empowerment. In this way one is not born sovereign since one is not born with power. One is dependent upon others who hold sovereignty over you. Thus Aristotle argued that family was the basis of political communities.[10] The implication that political community is rooted in family, or understood as the collective extended family, is already drawn from Plato’s dialogues like the Euthyphro, the Republic, and the Crito. The contest between family and law is visibly manifested in Euthyphro’s fidelity to the law over his father, the collectivization of family as described in the supposed ideal state in the Republic, and the discourse on the Laws in the Crito all draw upon filial language or play with the contestation between family, law, and sovereignty. (Nor is it surprising that since the Euthyphro is set in Socrates’ final days that we see the thematic connection between the dialogues and that since the gods and the biological family unit has been superseded by the state that the Laws of Athens will come to embody what was hinted at in Euthyphro more forcefully and visibly in the Crito.)

Continuing onward in history, the medieval Islamic philosopher Ibn Khaldun also noted that it is family which is the first refuge from the harshness and injustice of the world—that is, the turn to family for protection and empowerment marks and establishes the family as the first unit of sovereign power.[11] Likewise, Catholic social philosophy holds that the family is the first unit of the social order; the “original cell of social life.”[12] Even Jean-Jacques Rousseau agreed, insofar that, “The oldest of all societies, and the only natural one, is that of the family; yet children remain tied to their father by nature only so long as they need him for their preservation.”[13] The weight of philosophical examination concludes that the family is the first cornerstone and realization of sovereign power in the world.[14]

Since sovereignty is marked by power, power comes in numbers (at least historically). Alone, a person is weak, powerless, and at the mercy of the world and others. In a community a person is strengthened, not on his own accord but because of the relative power gained by being a member of a group. Humanity’s political, or social, animus aims at the fulfilled life. Or, the good life as Aristotle claimed.[15] Accordingly, all human communities and constructive endeavors aim at easing the existential worry of being related to, or remaining in the state of, bare life. For without the community which serves as the cornerstone for the possibility of fulfilled life—in the most visible case, and generally agreed upon by most philosophers historically, the family—human life would be bare, harsh, and short akin to the life in the state of nature as Thomas Hobbes described in Leviathan.

Therefore, the head of the family is the penultimate sovereign in sovereignty’s most basic embodiment just as Livy articulated in his History of Rome and Robert Filmer defended in Patriarcha. The paterfamilias is the first wellspring of sovereignty, the first source of the possibility of having fulfilled life, and the first construction to deliberately aim at achieving fulfilled life. But the point of the family head, the father in ancient Greek and Roman culture and society, as the original arbiter of sovereignty, is important to know when understanding the examination of sovereign power in the Crito—especially given the filial language used in the discourse on the Laws.

Bare Life

The idea of bare life extends well beyond the Greek dichotomy of bios and zoē. Today, people are likely familiar with the bare life side of the Greek distinction through the idea of the state of nature presented by Thomas Hobbes or the devolution of the state of nature into the state of war in John Locke’s reimagining. In either case, it is only through the commonwealth—the political community—in which fulfilled life can be consummated without fear of harm or violent death.

Aristotle was adamant that the telos of life is consummated by living in a political community, “When several villages are united in a single complete community, large enough to be nearly or quite self-sufficing, the state comes into existence, originating in the bare needs of life, and continuing for the sake of the good life. And therefore, if the earlier forms of society are natural, so is the state, for its is the end of them.”[16] Moreover, Aristotle linked human teleology and flourishing with political life on several occasions, furthering the connectivity between bios and polis, “Hence every city-state exists by nature, inasmuch as the first partnerships so exist; for the city-state is the end of the other partnerships, and nature is an end, since that which each thing is when its growth is completed we speak of as being the nature of each thing…the object for which a thing exists, its end, is its chief good.”[17] The chief good for the human is fulfilled life in political community.

The implication of Aristotle’s state arising out of the bare needs of life whereby the perfection of life is found in political community calls into question why bare life is problematic in the first place. The closest understanding one can glean from Aristotle is that an isolated person is generally incapable of the good life. In coming across a tribe, the isolated person is easily defeated. In coming across a city, the isolated person is defeated. Alone, a person amounts to little or nothing in Aristotle’s teleological conception of humanity. Whatever sovereign power a human has by fact of their physical endowment is lost when coming across tribes, groups, cities, or various other collectives of humans who, in their togetherness, exert a greater power (and, therefore, sovereign power) than any human can ever exert alone.

Subsequently, there is a twofold understanding of the problem of bare life in Greek thought. First, a person stuck in bare life is not living according to their telos. “Man is by nature a political animal.”[18] Second, Aristotle implies that it is in the state of bare life a human is weak, would be subject to domination by larger groups and would be unrefined and uncultured—remaining more a brutal animal than an exquisite human as a result. In essence, a person living in the state of bare life is living more like an animal than a human. It is only through political life that humanity is perfected, “For man, when perfected, is the best of animals, but, when separated from law and justice, he is the worst of all since armed injustice is more dangerous, and he is equipped with arms, meant to be used by intelligence and virtue, which he may use for the worst ends.”[19] For Aristotle the bios-zoē distinction leads to a dialectic between living in accord with the good life and living in accord with animal passions. Bare life is the animalistic side of humanity.

It is not a stretch, then, to see Aristotle as having some sense of a state of nature wherein humans use their physical strengths, in the form of arms and legs, for the worst of possible ends. This would entail some sort of physical violence and war to be sure. To this end Aristotle quotes from Homer in drawing a representation of the bare man, whom is “either a bad man or above humanity”[20] and is subsequently “lost to the clan, lost to the hearth, lost to the old ways, that one who lusts for all the horrors of war.”[21] The bare man is lost, detached, and otherwise alienated from civilization and lusts for domination. He lusts for “all the horrors of war.” From Aristotle’s perspective, not only does political community refine beastly humans to their perfectible and better ends, it is also the fulfillment of humanity’s teleological nature. The bare man, detached from political community, is left in a state of lusting after the horrors of war and being the worst of animals in being giving over to his animalistic desires.

Modern readers are already familiar, then, with the idea of bare life in the more brutish and picturesque portrait as painted by Thomas Hobbes as hitherto stated. For it is in this state of nature, which is a state of bare existence in Hobbes’ account, that leads humans to deal violently with one another leading to the war of all against all exhausting life to be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”[22] This unpleasant life, one that is ultimately untenable, is a dramatic picture indeed. Yet even John Locke paints the same portrait of bare life in the Second Treatise.

It is commonplace nowadays to see Hobbes and Locke as being two sides of the same coin. Locke’s idyllic state of nature, if one recalls, is only superficially more peaceful than in Hobbes’ account because it eventually, and quickly, descends into the state of war which he described in the third chapter of the Second Treatise. In the unceasing competition for self-preservation, the iteration of the nature (which is only self-preservation) must descend into war before it unites humans to cease their conflict and abandon their role as individual judge, jury, and executioner of the law of self-preservation and enter into civil society. This constitutes the paradox of bare life in Locke’s account.

The law of nature, which is self-preservation, is moral. But Locke’s law of nature is moral only insofar as it must first reduce humans to constant fear and even, for some, death, in that state of war before awakening human sentimentality to move beyond this untenable brute subsistence leading to humans to cooperate and work together in the new commonwealth society. Locke also made clear that the state of war is the result of power clashing with power, and destruction comes to person when they fall into the powerful clutches of others.[23] “To avoid this state of war,” Locke wrote, “is one great reason of men’s putting themselves into society, and quitting the state of nature: for where there is authority, a power on earth, from which relief can be had by appeal, there the continuance of the state of war is excluded, and controversy is decided by that power.”[24]

The formation of political society not only allows for fulfilled living in Locke’s account (as well as Hobbes’), but sovereign power is also transferred from persons to the state. Rather than remaining the individual judge, jury, and executioner in the state of nature—which is the exertion of sovereign power and an expression of absolute freedom in the original state of nature—sovereign power is transferred to the commonwealth authority to mediate disputes between persons. This returns us to Socrates’ discourse on the Laws wherein sovereign power was held by the Laws and not Socrates. Socrates, like Locke’s primordial human who quit the state of nature, has transferred sovereign power to “that power” of political society to avoid the state of war and secure a peaceable living which should lead to a fulfilled life.

What is clear from the traditions of bare life in philosophy, in whatever way that they manifest themselves or are imagined by the philosophers, is that life is untenable in its so-called bare state of existence. It is brutish. It is a state of conflict. One’s life is always at risk. It is impossible to live a fulfilled and meaningful life, either because of the fighting against one’s nature or by the state of war leading to constant fear and, oftentimes, violent death in the encounter and engagement with other humans. Bare life is to be avoided and is subsequently overcome by the integration of the human with the sovereign power of the political community and its legal structures and juridical apparatus.

Sovereign Power in the Crito

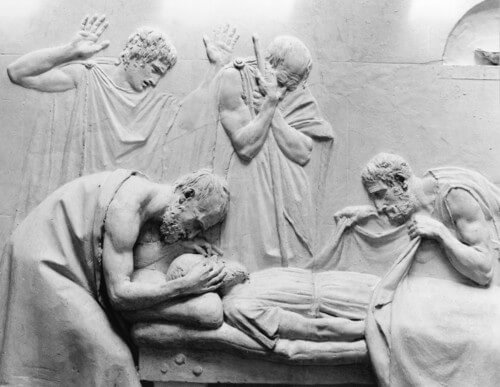

The correlation of family, especially one’s father, with the Laws of Athens is something that no reader should miss when examining the Crito. Plato goes to great lengths to highlight this filial divinization of the Laws in the dialogue. Furthermore, one should be aware of the undercurrent of Greek philosophical thought concerning fulfilled life and bare life as I’ve just outlined before delving into the Crito. Additionally, it is sometimes easy to forget that Socrates in in a prison cell once one is wrapped into the heart of the conversations between Crito and Socrates. And the prison cell that Socrates is in is a structure of sovereign power wherein the prisoner, Socrates in the dialogue, is reduced to a state of bare life. Just through the material positioning of Socrates in the Crito, one should understand where true sovereign power lay and who is sovereign from behind the scenes. Though living in Athens, Socrates is depicted in a bare state of existence in the dialogue.

The discourse on the Laws begin, “Tell us Socrates, what do you intend to do? Do you intend anything else by this act you’re attempting than to destroy us Laws, and the city as a whole, to the extent that you can?”[25] It is not inconsequential that the opening discourse on the Laws is the quintessential example of the state of exception described by Schmitt and Agamben. There is a struggle at hand whereby the existence of the state—the city and its laws—is potentially at risk from the person of Socrates. The state is in a state of emergency, or more succinctly put, the state believes that it is in a state of emergency which has led to its confrontation with Socrates in this struggle to the death which is a struggle over exercising sovereign power.

Authority is tied to sovereignty insofar that the authority is embodied and expressed by the sovereign who decides on the exception. When authority is jeopardized this means sovereignty is also jeopardized, “[D]o you think a city can continue to exist and not be overthrown if the legal judgments rendered in it have no force, but are deprived of authority and undermined by the actions of private individuals?”[26] Not only would the state cease to exist, but the good lives of the multitude of other citizens would also be endangered if Socrates fled. That is the impetus of the rhetorical question put to Socrates by the Laws. It would also show to the population the futility of the force of the law which would correlate to a lack of sovereignty if sovereign power had no force in the absence of those “legal judgments rendered [having] no force.”

The juxtapositional dialogue in the prison cell is whether Socrates, or the Laws of Athens, is sovereign. Only one can be sovereign. To whom does sovereign power lay with, then, is the question Plato is examining. Does it lay with Socrates? Or does it lay with the Laws? Does Socrates have the sovereign power to decide on the exception, thereby making himself the exception to the legal judgments rendered, or does the state, in having pronounced its exception marking Socrates out as an enemy to be condemned, have sovereign power? There is a zero-sum dialectic that is presented in the discourse. For whoever is sovereign necessitates the reduction of the other to a state of bare life. Since surrounding imagery and the place of Socrates (in a prison cell) already hints at where sovereign power resides, the discourse continues to unfold and only serves to reinforce this reality that it is the Laws, and not Socrates, who is sovereign.

Moreover, within the first few paragraphs of the discourse, ἀπολέσαι and ἀπολλύναι appear multiple times.[27] “Come now, what charge have you to bring against the city and ourselves that you should try to destroy us . . . if we try to destroy you, believing it to be just, will you try to destroy us Laws and your fatherland, to the extent that you can” the Laws ask.[28] As the discourses unfolds, the Laws continue to speak in heightened war-like language and engage in a filial divinization of themselves invoking the concept of filial sovereignty as the first cornerstone of sovereign power:

“Or are you so wise that it has escaped your notice that your fatherland is more worthy of honor than your mother and father and all your other ancestors; that it is more to be revered and more sacred and is held in greater esteem both among the gods and among those human beings who have any sense; that you must treat your fatherland with piety, submitting to it and placing it more than you would your own father when it is angry; that you must either persuade it or else do whatever it commands; that you must mind your behavior and undergo whatever treatment it prescribes for you, whether a beating or imprisonment; that if it leads you to war to be wounded or killed, that’s what you must do, and that’s what is just—not give way or retreat or leave where you were stationed, but on the contrary, in war and law courts, and everywhere else, to do whatever your city or fatherland commands.”[29]

The language used in the discourse, in its militaristic and warlike presentation, is deeply revealing. It represents, per the issue of the state of exception and sovereign power, the primacy of sovereignty of the state over the person.[30] State control over one’s life is even included insofar that if one is to die, to be killed, in serving the fatherland then so bit it—“that’s what is just.” The sovereignty of the Laws is totalizing over Socrates and has reduced Socrates to a state of bare existence; Socrates is in a condition of powerlessness.

The inclusion of this language paints that militaristic undertone that the state of exception is based on. For war is the clearest emergency in which something constitutes a threat to sovereignty. Part of the development of sovereignty in the context of the state of exception is “the state’s immediate response to the most extreme internal conflicts.”[31] The reader of the Crito is meant to be left with the impression of deadly and decisive combat between Socrates and the Laws. The conflict between Socrates and the Laws is an internal conflict from which the state, the Laws in the discourse, is responding to. The fate, life, of both Socrates and the Laws hangs in the balance as the language intentionally makes clear. And there is no doubt left in the reader’s mind as to which life is more important; there is no confusion as to whose life is controlled and, therefore, who is sovereign and who is not sovereign during the course of the discourse.

This imagined dialogue between Socrates and the Laws also uses filial language to describe the Laws—something that integrates the sovereign power of the Laws with the sovereign power of family and, especially, the filial patriarchal head. Since family is already established, and taken as a given, to be the foundational pillar of the principle of sovereignty in its simplest form, the Laws’ use of filial language to becoming fatherland and one’s true father is no small subtlety. In declaring to Socrates that he must “treat [the fatherland with piety, [and] submit to it,”[32] the Laws make clear that the sovereignty of the state is total over him like the sovereign power of a father over a young child who is dependent upon the father for life. What is more striking is the divinization of the filial state, “Or are you wise that it has escaped your notice that your fatherland is more worthy of honor than your mother and father and all your other ancestors; that it is more to be revered and more sacred and is held in greater esteem both among the gods and among those human beings who have an sense.”[33] The state is the superior fatherly entity than Socrates’ own parents and all his ancestors combined; it is the state which is highly favored and worthy of reverence moreover than Socrates’ flesh and blood ancestors and parents.

Carl Schmitt defined the political from its theological genus, “All significant concepts of the modern theory of the state are secularized theological concepts not only because of their historical development…but also because of their systematic structure, the recognition of which is necessary for a sociological consideration of these concepts.”[34] In this manner Schmitt merely followed in the footsteps of Hegel who declared, “The State is the Divine Idea as it exists on Earth.”[35] The divinization of the political is the twofold legacy of being that secularized embodiment of God’s sovereignty and how, in God, much like in the bios politikos, one’s life is fulfilled. But this entails surrender to the sovereign power in order to have a fulfilled life. As one must submit to God, so too must one submit to the state to actualize a meaningful life.

The modern state is not merely the derivative embodiment of ancient theological constructs and ideas as Schmitt had it. The ancient state was equally the derivative embodiment of such theologico-political constructions. The state’s systematic structure is the hierarchy of the body united by the fatherly head. The sovereign state that Plato sees as reducing Socrates to bare life may lack the latter addendums and intricacies of the systematic Christian theological project, but it is already embodying an expansive and divinized notion of paterfamilias to exercise its sovereign power. As Socrates ends the discourse on the Laws, the Laws declare triumphantly to him, “it is impious to violate the will of your mother or father, it is yet less so than to violate that of your fatherland.”[36] From this perspective, the conversation between Crito and Socrates is not about just and unjust laws and the correlative actions that one should take regarding just and unjust laws. The language of the Crito is that of the bios-zoē distinction and how this distinction relates to the problem of sovereignty.

After all, Socrates claimed that since he has chosen to live in Athens he has chosen to live under the sovereign laws of Athens. Socrates has willfully and willingly chosen this life, which is now coming to an end. As such, Socrates implies that having decided to live under the laws of Athens he was willing to subject himself to the laws whereby his sovereignty—now tied to the body politic of Athens—was always beneath that of the sovereign body as part of the whole.

Bare Life in the Crito

The continuation of the paradox of the bios-zoē distinction continues in Plato’s reflections of Socrates’ bare state of existence in relationship to the state. The political body is instituted to provide a fulfilled life. But Plato is aware, as hitherto highlighted, how this often leads to the reduction of the person back to the state of bare life despite the avoidance of bare life as what was promised by bios politikos. Not only is part of the reason for Socrates accepting his predicament on account of the sovereign power of the state which has rendered him powerless, but it is also because Socrates claimed to have lived a fulfilled life—which leads him to be accepting of death and his return to the state of bare existence as he is locked up in a prison and preparing for his death. He lived well and is accepting of the fact that his having lived well has paradoxically placed him into this predicament of having been reduced to bare life once again.

While in prison Socrates sets up the discourse on the Laws, which I have just examined, in typical Socratic fashion. He condescendingly commends Crito’s enthusiasm before launching into the Socratic dialectic, “We must therefore examine whether we should do what you advise or not.”[37] Socrates proceeds to prepare the discourse of the Laws as the “knowledgeable and understanding supervisor” who should be followed with regard to “eating and drinking” lest one does harm to one’s own body.[38] Crito understands the analogy right away; for when Socrates asks him what the harmful effect is and where the harm is done Crito correctly answers, “Clearly it’s in his body, since that’s what it destroys.”[39]

This subsequently launches Socrates into a criticism of bare life and a defense of political life insofar that the polis is the body writ large which one is attached to and personally benefits from by being a constitutive part of the larger body—in other words, a citizen. The exoteric nature of this discourse on the body is not so much concerned with the opinions of the masses, as much as it is the benefit of the belonging to the political community in the particular. For the importance of the avoidance of bare life is the same as Aristotle’s pronouncements about the state emerging to overcome the despair and hardship that characterizes bare life.[40]

Bare life is avoided by becoming a member of a body by which one has a fulfilled life but only through becoming a member of that community. This coming into a body politic is desirable because “[we are] made better by what’s healthy” according to Socrates.[41] In the context of Socrates’ and Crito’s conversation, along with the tradition of Greek political thought, this means belonging to a member of a political body and being a healthy and productive constitutive part of that larger body. The victory of the body, which is the state, is totalizing over the course of this incorporation into the body like a slow-growing virus. We should not destroy “the part of us that is made better by what’s healthy” Socrates tells Crito.[42] From the conversations between the two, and between Socrates and the Laws, what is visibly clear to the reader is that apart from a body we live miserable and wretched lives: bare, difficult, and tough. Given the severity of the dichotomy, Crito naturally, and quickly, agrees with Socrates that it is better to avoid bare life than embrace it. As Socrates eventually tells Crito, “The most important thing isn’t living, but living well.”[43]

Here, Socrates contrasts the difference between (bare) living and living well. In the bare state our bodies are often continuously injured, maimed, and we struggle to live the good life separated from the rest of the body. Separated, therefore, from the good of the community (which is the body politic) our lives are instantiated representations of that “wretched, seriously damaged body.”[44] Isolated and separated, we are weak and endangered. To simply live is not living well. And to not live well is to fail at consummating one’s political nature. Socrates informs Crito of this reality by way of rhetorical questions:

Come then, suppose we destroy the part of us that is made better by what’s healthy but seriously damaged by what causes disease when we don’t follow the opinion of the people who have understanding. Would our lives be worth living once it has been damaged? And that part, of course, is the body isn’t it…Then are our lives worth living with a wretched, seriously damaged body?[45]

The discourse concerning whether people will think poorly of Crito for not wanting to save Socrates is really a discourse about the benefits of living as a member of the political body and not a conversation about friendship and the opinion of others. It is a discourse about why bare living is not desirable and why humans put themselves into a sovereign political body despite the loss of “individual liberty.” This attempt to resolve the crisis of individual liberty in an original state of nature is equally the question being wrestled with by modern philosophers who give their own interpretative fantasy about how this movement to the political body took place.

If life was just about bare life—just “living” as it were—humans would accept the condition of bare life and revel in it. But life is not just about bare life, it is also about living well—that qualified, or fulfilled, life that the political is meant to consummate. To live well one must place themselves into a political body. “And the argument that living well, living a fine life, and living justly are the same—does it still stand or not?” Socrates asks Crito.[46] Crito immediately agrees with what amounts to a rhetorical question. That damaged body which is not worth living as is the damaged body that would transpire should Socrates flee at Crito’s request. This is testified to when the discourse on the Laws pivots to a soliloquy on the virtues of filial piety.[47] Failure to obey the laws of the fatherland leads to an undermining of authority which would bring harm to the entire political body as it would be thrown into a state of chaos if the laws of the city were rendered to having no force.[48]

Socrates has concern for others and their good lives—or potentially good lives—at the same time as reflecting upon his own life. Socrates truly is examining, here, in the jail cell, the questions relating to the good life as a political philosopher would. This is, of course, precisely what he told Crito their task would be at the onset of his arrival: Socrates is examining the nature of the political body in its totality which includes the fundamental questions of bare life and fulfilled life.

This conversation on respecting, or allowing, the thoughts of the majority impacting our actions are paradoxically illuminating for several reasons. First, as hitherto demonstrated, the discourse is not about being subject to the whims and opinions of others as much as it is about the criticism of bare life, just living, and the benefits of life in the city, or “living well.” Second, the discourse, in preparing the reader for the discourse on the Laws which follows, is not about Socrates, per se, at all. It is a general philosophy of life and political life. Third, that Socrates discusses the importance of living well foreshadows his arguments as to why he is willing to accept the decrees of the Laws of Athens immediately after having finished the discourse on the sovereign powers of the Law. Fourth, the argument laid out by Socrates is meant for reader to realize the greater paradox of living well. Despite living well, Socrates (representative of all persons from Plato’s perspective in this dialogue) has nevertheless been reduced back to bare life as exemplified by his imprisonment and coming death (by drinking hemlock).

The reduction back to bare life is on account that Socrates has already lived a good, satisfying life. The purpose of life, at least to him, has been fulfilled:

“Socrates . . . we have the strongest evidence that you were satisfied with us and with the city. After all, you’d never have stayed at home here so much more consistently than all the rest of the Athenians if you weren’t also much more consistently satisfied. You never went anywhere for a festival. Except once to go to the Isthmus. You never went anywhere else, except for military service. You never went abroad as other people do. You had no desire to acquaint yourself with other cities or other laws. On the contrary, we and our city sufficed for you. So emphatically did you choose us and agree to live as a citizen under us, that you even produced children here. That’s how satisfied you were with the city.”[49]

Plato drives home this paradox of political life in the Crito: Political life gives us a home and refuge, nurtures us, and helps us live better and more fulfilled lives. Yet in accepting this we are bound to the laws of the city, the state, or country, whereby you have “commitments . . . as a citizen under us.”[50] This can, and often does, lead to the state exerting its absolute sovereignty and reducing people—whom are now deemed threats to the sovereignty of the state—back to bare life. The problem that Plato is exploring is how bios politikos does not fully eradicate the problem of zoē despite its promises to do so.

Socrates, insofar that he had begun to threaten the sovereignty of the state with some of his teachings to the youth of Athens, was subsequently judged an enemy of the sovereignty of the state. This is evidenced to the lengthy discourse on the Laws ripe with militaristic and warring language. Chaotic life, as bare life, is itself a life that is not worth living. Political life, as allowing for fulfilled life, is worth living. But where does sovereignty now reside? The entity that provides for fulfilled living? Or the human who, alone, amounts to nothing but bare life and lacks sovereign power so long as he remains isolated and separated from others? But this returns us to the problem of bare life; alone, exiled, and isolated, the human is weak and at the mercy of larger bodies or communities who wield and can exert a greater sovereign power than any single person can.

The Dilemma of Sovereign Power and Human Life

The Crito is an intricate and complex dialogue examining the issues of sovereign power and bare life. From Plato’s perspective there is an almost inescapable dilemma concerning the relationship between the two. Satisfied, or fulfilled life, is envisioned as only possible in the realm of the political—the highest good in life is to be part of the political community. Bare life, which is as Socrates said, simply about “living,” is not the aim of human life. The trial of Socrates is the trial of sovereign power and bare life. Sovereign power is that which one turns to in their moments of weakness. Family is the first building bloc of sovereign power and refuge from bare life. The emergence of the state, or the body politic, is envisioned as an enlarged family (which is especially made clear in Socrates’ imagined the discourse on the Laws). However, since one had to turn to someone, or something, to escape bare life, this shows that purely atomized living and self-centeredness – that idea of the self-sustaining and self-sovereign self – is untenable and unfeasible. For if one remains alone and isolated in bare life, while they are, in some sense sovereign, their sovereign power will always lack in comparison to filial or group sovereignty. Therefore, is such a person sovereign since they are at the mercy of more powerful forces?

The turn to bios politikos allows for a certain collective sovereignty in the form of the body politic. This also allows for that fulfilled life to be made possible. But this also entails that the political body is sovereign over the self. While this is what the good life entails, and while Plato sees the city—the embodied manifestation of bios politikos—as natural with positive potential, he is equally warning his readers that the life, insofar that it is tied to bios politikos, comes with the possibility of being reduced back to bare life in states of war and emergency wherein the state sees its sovereignty as threatened. This can be from external or internal forces (or both simultaneously). As seen in the case of Socrates, Plato’s warning is more concerned with the very real possibility of perpetuating that “state of exception” to the domestic body politic, wherein citizens (represented in the dialogue through Socrates) are always in a state of risk to be reduced to bare life. There is an irony that Plato sees in all of this. In the human bid for fulfilled living, which is the movement away from bare life, one can never fully move away from bare life – in fact, the very consummation of fulfilled life always retains the possibility of slippage and forced reduction back to bare life.

The empowered polis can now provide the plane for meaningful life to be consummated (bios politikos), but it also wields its power to reduce people back to the state of bare life which the end of political community is supposed to overcome when it feels threatened. Thus, it is critical to recognize where this dialogue takes place—in a prison cell, the very place that exemplifies the state of exception. Plato, while not rejecting the reality of bios politikos, is warning us of the potential false promises of bios politikos; something that Aristotle never considered a possibility.

There is a crisis of sovereignty that Plato examines in the plays set leading up to the death of Socrates. Where does sovereign power lay? In the state or in the self? In Socrates’ death we see that the state ultimately triumphed. Yet it is not apparent that Plato ascents to this supremacy of the state. Instead, we see Plato trying to understand how the state became sovereign over the citizen. As such, Plato is in fact warning about the supremacy of the state and how it comes about through the destruction of the family and how the divinization of the state emerges in the absence of the family.

The state becomes pater familias when the biological family unit dissolves. Yet it is also true that under the supremacy of the state we live more comfortable and secure lives than we could alone or with just our family. This paradox requires us to balance our loyalties or suffer the extremes of bios and zoē. Sovereignty under bare life is inconducive to the good life. But does the good life, as Socrates defended it in the dialogue, require the surrender of individual sovereignty to the state? There is no indication that Plato believed this. Rather, by having Socrates and the Law speak, and in revealing the hubris and extreme power of the state, Plato seems to suggest the state was in the wrong and we mustn’t surrender sovereignty entirely over to the state. After all, we know Plato felt a great injustice had been committed against Socrates in his arrest and death.

Notes

[1] See Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller- Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), 1. Although Agamben’s main focus is the correlation of homo sacer (in Roman Law) with the status of zoē from Greek thought, I wish to focus on the bios–zoē distinction especially at it relates to the implications of the dialogue in Crito. While not forcibly exiled from the community, as is the status of homo sacer in Latin law, in some ways Socrates was marked as homo sacer insofar of his being reduced to the status of zoē prior to his death.[2] Ibid.

[3] Aristotle, trans. Benjamin Jowett, Politics, 1.2.1252b-1.2.1253a. All citations from Aristotle’s Politics are taken from Benjamin Jowett’s translation.

[4] Plato, trans. C.D.C. Reeve, Crito, 52b-52c. Unless otherwise noted, the citations from Plato’s Crito are taken from the C.D.C. Reeve’s translation.

[5] Carl Schmitt, Political Theology, trans., George Schwab (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 5.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid., 6.

[8] Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception, trans. Kevin Attell (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 1.

[9] Ibid., 2.

[10] Aristotle, 2.1261a. Aristotle sees the family as the mean between the person and the state. An entire state cannot be conceived of as the whole family as this destroys the foundational pluralism that Aristotle conceives as the basis of the political community. This totalizing aspect of the family being analogous to the state is something that Aristotle criticizes. He does not mean to criticize the principle of the family as the basis of political community but criticizes the excess to which this sometimes takes.

[11] See Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah, trans. Franz Rosenthal, ed. N.J. Dawood, (Princeton University Press, 2005), 95-97.

[12] See the Catechism of the Catholic Church for its analysis of family and the social order in its examination and exegesis of the Fourth Commandment, nos. 2197-2257.

[13] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract, trans. Maurice Cranston (New York: Penguin Books, 1968), 50. It is true that Rousseau also thinks the bonds of family will dissolve when the individual is powerful enough to survive on his own – nevertheless Rousseau acknowledges the importance of the family unit in the needful dependence of a newborn to their parents before growing strong enough to become independent of them. While many modern philosophers envisioned the dissolution of the family unit as a necessary prerequisite for individual freedom to be consummated, their recognition of family as the first unit of sovereign power and structural authority fits with the ancient recognition of family as the building block of social order.

[14] This understanding of the family, especially the family head, as the arbiter and origo of sovereignty is important to understand as it relates to the nature of the conversations contained in Crito.

[15] See Aristotle, The Politics (1.1252a). Since Aristotle’s teleological conception of life rests on eudemonia, happiness, then the aim of political life is to reach a certain state of satisfaction with life. This is also important, in my view, in understanding Socrates’ arguments when talking with Crito. Plato is also a eudemonist. So this strand of eudemonistic thinking through Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy differs in understanding rather than on teleological principles.

[16] Aristotle, 1252b.

[17] Ibid., 1253a.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Homer, The Iliad, trans. Robert Fagles (New York: Penguin Books, 1990), IX.73-75, p. 253.

[22] Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (New York: Barnes & Nobles, 2004), 77.

[23] John Locke, Second Treatise on Government, ed. Ian Shapiro (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), § 16.

[24] Ibid., § 21.

[25] Plato, 50a.

[26] Ibid., 50a-50b

[27] ἀπολέσαι appears in 50b, ἀπολλύναι appears in 50d and 51a twice. The use of this language evokes deep and intense conflict. Plato could not have intended anything other through the careful use of these words. Both words invoke the meaning to destroy, thereby reiterating the emphasis of fatal conflict.

[28] Plato, 50d-51a

[29] Ibid., 51a-51b

[30] The Greek words Πόλεμον and πολέμῳ are used in 51b, seemingly commanding Socrates as a soldier to do his duty to preserve the fatherland, or state. In this description the state wields its sovereignty over Socrates. The continued militaristic and warlike language also implies the sovereignty of the state in jeopardy. This puts the state in the position of the state of exception, in its state of emergency, where sovereignty is defended and the reduction of human life – in this particular case that of Socrates – commences.

[31] Agamben, State of Exception, 2.

[32] Plato, 51b.

[33] Ibid., 51a.

[34] Schmitt, 36.

[35] Georg W.F. Hegel, The Philosophy of History, trans. J. Sibree (Mineola: Dover Books, 2004; 1956), 38.

[36] Plato, 51c.

[37] Ibid., 46b.

[38] Ibid. 47b-47c.

[39] Ibid., 47c.

[40] Aristotle, 1.2.1252b-1253a

[41] Plato, 47d.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid., 48b.

[44] Ibid., 47e.

[45] Ibid., 47d-47e.

[46] Ibid., 48b.

[47] Ibid., 51a-51c.

[48] Ibid., 50a-50c.

[49] Ibid., 52b-52c.

[50] Ibid., 52d.