Reflections on Russell Kirk

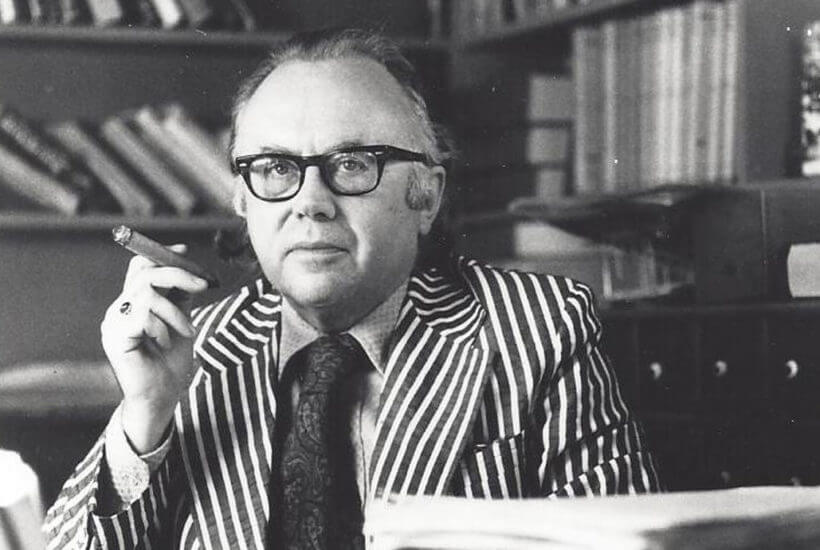

One hundred years ago was the birth of Russell Kirk (1918-94), one of the principal founders of the post-World War II conservative revival in the United States.[1] This symposium examines Kirk’s legacy with a view to his understanding of constitutional law and the American Founding. But before we examine these essays, it is worth a moment to review Kirk’s life, thought, and place in American conservatism.

Russell Kirk was born and raised in Michigan and obtained his B.A. in history at Michigan State University and his M.A. at Duke University, where he studied John Randolph of Roanoke and discovered the writings of Edmund Burke.[2] His book, Randolph of Roanoke: A Study in Conservative Thought (1951), would endure as one of his most important contributions to conservatism.[3] Kirk graduated from Duke in 1941, worked at Rouge plant at Ford Motor Company, and later entered the U.S. Army where he was stationed in the Chemical Warfare Service in the Great Salt Lake Desert. After his discharge, he became an instructor at Michigan State. In 1946, he took a leave of absence to research conservative thinkers in England and America at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland.

The resulting manuscript, “The Conservatives’ Rout,” earned him his doctorate in 1952 and was published in 1953 as The Conservative Mind.[4] The book received national attention and launched Kirk’s career as a public intellectual. In The Conservative Mind, Kirk uncovered a conservative tradition in Anglo-American civilization that had begun with Edmund Burke’s defense of liberty and rights and was continued by a group of varied thinkers such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Adams, Alexis de Tocqueville, Orestes Brownson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Irving Babbitt, and T. S. Eliot. This view of conservatism would later be referred to as “paleoconservatism” and joined libertarianism and anti-communism to establish the modern conservative movement in post-World War II America.

With the critical and financial success of The Conservative Mind, Kirk resigned from Michigan State and moved permanently to his ancestral home of Mecosta, Michigan. Although he would lecture on college campuses and accept teaching posts for short durations, he became an independent man of letters, writing twenty-six nonfiction works, three novels, three books of collected stories, approximately 2,000 articles, essays, and reviews, 2,687 short articles for his nationally syndicated newspaper column, “To the Point” (1962-75), and a monthly National Review column, “From the Academy” (1955-81).[5] Kirk also founded the conservative journals, Modern Age and The University Bookman, and he even entered into politics, campaigning for Barry Goldwater in 1964 and serving as the Michigan state chair for Pat Buchanan’s presidential campaign in 1992. For his contributions to American intellectual, cultural, and political life, he was awarded the Presidential Citizens Medal in 1989 by President Reagan.

According to Russell Kirk, conservatism did not offer a universal pattern of politics for adoption everywhere. It was “not a political system and certainly not an ideology.” Rather, it was “a way of looking at civil social order” with general principles applied in a variety of manners depending upon the country and historical period.[6] These principles were 1) a transcendent or enduring moral order, 2) social continuity, 3) prescription (i.e., “the wisdom of one’s ancestors”), 4) prudence, 5) variety, 6) imperfectability, 7) freedom and property closely linked together, 8) voluntary community, 9) prudent restraints upon power and human passion, and 10) the recognition that permanence and change must be reconciled in society.[7]

What held these principles together to form a conservative disposition was the “moral imagination,” a faculty of moral knowledge where humans intuitively perceived “the right order in the soul and the right order in the commonwealth.”[8] Imagination, not calculative reason, was what fundamentally defined human beings and society for Kirk. The battle, therefore, was not among competing programs of material betterment but between differing imaginations: Rousseau’s “noble savage” and Bentham’s utilitarianism versus Burke’s defense of tradition and Eliot’s Christianity. For Kirk, the conservative moral imagination was the correct one in its acknowledgement of a transcendent moral order that was reflected in nature, human nature, and society. The moral imagination drew ralof the moral imagination are drawn from the important aspects of tradition and social associations from the important aspects of tradition and civil associations (e.g., piety, prudence, the family) and integrated them into a working moral knowledge that included reason, sentiment, habit, and intuition.[9] Although these values were universal for Kirk, they were manifested in a variety of ways dependent upon the age, place, and culture.[10]

The two most important influences on Kirk’s conception of the “moral imagination” were Edmund Burke and Irving Babbitt.[11] The phrase itself, the “moral imagination,” was taken from Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, which described how the moral imagination gave dignity to human beings and allowed them to see the highest qualities of human nature.[12] Burke influenced Kirk’s views that humans were necessarily embedded within a web of tradition, continuity, and social institutions and therefore should follow their “moral imagination” instead of relying solely on individual reason. Kirk also agreed with Burke’s defense of tradition that it provided meaning and stability to people and that society was a contract between the dead, the living, and the yet to be born.[13]

Irving Babbitt also was instrumental in developing Kirk’s thought about the moral imagination. Babbitt was an American writer, academic, and literary critic who was a leading figure of the New Humanism, a movement that emphasized imagination–as represented in literature, culture, and education–in determining the perspective and actions of individuals and society.[14] Kirk adopted Babbitt’s understanding of the imagination in its need to regulate morality and agreed with Babbitt’s condemnation of Rousseau’s “idyllic imagination”: undisciplined, sentimental dreams about reality that rejected restraints imposed by tradition.[15] Later Kirk would focus on the “diabolic imagination,” that which was inspired by perverse and obscene ideals or visions maintained by the likes of the Marquis de Sade and Karl Marx, in contrast to the “moral imagination.”[16]

Kirk’s “moral imagination,” consequently, is an integral explanation of social, political, and moral knowledge based in Christian humanist values and seeks continuity, stability, and gradual reform in society.[17] By contrast, ideology, which Kirk defined as “political fanaticism,” aimed to transform society and human nature.[18] The ideologue had “in his system no room left for Providence, or chance, or free will, or prudence” and therefore was “dogmatic and often utopian” and promised “the destruction of all things established and the creation of a terrestrial paradise.”[19] The ideologue believed that human nature could be transformed, contrary to Kirk’s belief that human beings were flawed creatures with a mixture of good and evil, whose possession of original sin accounted for their proclivity towards selfishness. To restrain human appetites, the “moral imagination” was required: “this collective and immemorial wisdom we call prejudice, tradition, customary morality.”[20]

Tradition—the “prescriptive social habits, prejudices, customs and political usages which most people accept with little question, as an intellectual legacy from their ancestors”—was indispensable in the moral education of individuals.[21] Because previous generations preserved and transmitted the latter through the family, school, and church, tradition was perceived as a good among most people. However, tradition does not equate to nostalgia or a resistance to all societal reform, as Kirk writes:

Traditions do take on new meanings with the growing experience of a people. And simply to appeal to the wisdom of the species, to tradition, will not of itself provide solutions to all problems. The endeavor of the intelligent believer in tradition is so to blend ancient usage with necessary amendment that society never is wholly old and never wholly new.[22]

Tradition must “be balanced by some strong elements of curiosity and individual dissent” so society can both preserve its best elements while reforming its worst ones.[23] It was in the realm of politics to accomplish this task.

For Kirk, politics was to be led by an aristocracy of merit, statesmen who were qualified by their superior virtue and wisdom in order to lead society away from only material impulses to the spiritual and social aspirations of the “permanent things” reflected in religious dogma, tradition, culture, habit, custom, and prescriptive institutions.[24] Society should be the “harmonious arrangement of classes and functions” with justice being each person receiving his or her due.[25] To achieve this, the Burkean statesmen must mediate between order (disciplining individual selfish impulses for ultimate spiritual purposes) and liberty (limitations placed upon individuals) for society: the common good is never static but dynamic, always needing statesmen to balance between imposing order and permitting liberty. Rather than occurring in a historical vacuum as an abstract reality, the right balance between order and liberty is found by statesmen in specific contexts and under concrete circumstances.[27] The extent of one’s liberty was dependent upon the amount of self-discipline the individual and society could achieve.

For Kirk, the principal threats to a well-ordered, free society were ideologies that rejected tradition and the “permanent things,” along with industrialization, urbanization, and mass consumer society, which uprooted people from their local communities and, consequently, subjected them to boredom where individuals no longer possessed a spiritual purpose. Kirk specifically criticized the ideologies of Marxism, which treated individuals as identical units under a compulsory equality, and liberalism, a de-spiritualized ideology that promoted government growth and authority at the expense of voluntary community and tradition. Both of these ideologies he saw as threats to a society of “ordered liberty.”[28] Kirk also listed industrialization and urbanization as dangers to a healthy society by supplanting local communities for a proletariat that shared mass entertainment and material consumption at the expense of knowing one’s neighbors and family members.[29] The result was social ennui when the “permanent things” were lost and devalued by society.[30] The “moral imagination” of the conservative had been replaced by the conformity to the crowd’s materialist and vulgar tastes.

To counter, or at least ameliorate, these threats, Kirk looked to reforming contemporary education as a way to conserve the “permanent things” of western civilization and thereby preserve order in society. For Kirk, the ethical, moral, and cultural character of a people was the foundation of society and, therefore, political matters could only be resolved if people were educated according to the conservative principles Kirk identified. The primary problem that plagued contemporary education for Kirk was its positivist nature: the predominance of the natural and social sciences, coupled with a progressive political perspective that neglected the arts and humanities, along with the values of tradition.[31] Higher education was even worse, suffering from “equalitarianism, technicalism, progressivism, and egotism”: an education for mediocrity rather than for leadership, practical and materialist knowledge over a theoretical and spiritual one, learning as free of compulsion instead of self-discipline, and following educational fads rather than understanding one’s own tradition.[32]

Kirk proposed a primary and secondary education of moral “dogmas” to be taught to children to counteract these threats: the traditional values of special beneficence; duties to parents, elders, ancestors; duties to children and posterity; the law of justice; the law of good faith and veracity; the law of mercy; and the law of magnanimity.”[33] He also suggested instruction in political dogma within moderation: to affirm the dignity of humankind, support of representative government, recognition of the tension between order and freedom, and the assertion of a humane and free economy. These dogmas were to be taught in the arts and humanities so students could develop their own “moral imagination,” such that when they went to college, they would be prepared to study the Great Books under a tutor-student model, Kirk’s ideal form for the university.[34]

Kirk’s enduring reputation as a major thinker of the twentieth century is assured by his resurrection of the conservative intellectual tradition in post-World War II America with the publication of The Conservative Mind. He also presented a strand of conservatism that was rooted in culture and community, in contrast to the individualism of libertarianism and the national greatness model of neoconservatism.[35] Unlike libertarians and neoconservatives, Kirk’s conservatism was chiefly nonpolitical in nature with its attention to morality, culture, and community. For conservatism to survive in the future, Kirk believed that conservatives had to rethink what they wished to conserve and, by doing so, must recognize that a healthy politics and sustainable policies were ultimately rooted in a culture of the “permanent things.”

This understanding of conservatism creates the possibility for it to reinvent itself to ever-changing circumstances, while retaining its principles in each new context. By stressing the “moral imagination,” Kirk’s conservatism can be adopted in a variety of ways, whether in history, politics, literature, philosophy, religious studies, and other disciplines of knowledge.[36] It can also be open to a diversity of politics and policies, since it calls for both imagination and prudence in the statesman. The lack of political doctrine in Kirk’s conservatism, unlike the libertarian’s fetishization of unbounded individual freedom or the neoconservative’s democratic triumphalism and support of national government, makes his politics free to address concrete problems as the specific context demands.

Today, the conservative movement is confronting a crisis of confidence, not sure what it stands for after the 2016 election of Donald Trump to the presidency.[37] The election of Trump also reveals the failures of American political, civic, and social institutions to address the concerns of Americans who feel left behind.[38] Instead of the incoherent populism that Trump represents, conservatives have offered several different answers. For example, Samuel Goldman suggests a new fusionism of constitutionalism, free markets, and traditional education; Greg Weiner calls for a return to a national constitutional conversation with Congress asserting its power; Yuval Levin, Patrick J. Deneen, Bradley J. Birzer, and Jack Hunter propose a Kirkean conservatism that addresses the alienation that Americans experience by strengthening civic and social associations like the family, church, and schools.[39] On how to move forward under present circumstances, the responses of conservatives are varied and at times in conflict with one another.

This symposium continues the conversation among conservatives as the best way forward in the age of Trump with a close examination of Russell Kirk’s account of conservatism. It explores Kirk’s understanding of constitutional law and the American Founding, what his contributions were to the conservative movement, and how they can help conservatives understand their present situation and look to the future. By exploring these issues, this symposium not only deepens our understanding of Kirk’s thought but also points to ways that conservatism can still be relevant.

Luke C. Sheahan’s “The Chartered Rights of Americans: A Kirkian Case for the Incorporation of First Amendment Rights” shows the salience of Kirk’s constitutional thought by examining the incorporation of the First Amendment. While Kirk rejected the idea of incorporation and other aspects of the Supreme Court’s First Amendment jurisprudence, Sheehan argues that incorporation may be interpreted as defending conservative development on grounds more amendable to traditionalists. Conservatives therefore should not automatically be hostile to the doctrine of incorporation but see when and under what circumstances it would be compatible with their principles.

Luigi Bradizza’s “Moderation and Extremism in Russell Kirk’s The Roots of American Order” looks at Kirk’s comparison between the American and French Revolutions, arguing that the former is a conservative revolution and the latter an ideological and utopian one. However, Bradizza examines Kirk’s interpretation of the American Founding in greater detail with some reservations. Specifically, Bradizza believes that Kirk misinterpreted Locke and thereby was not able to provide a robust theory of politics because it lacked an account of natural rights.

Kirk’s conservatism differentiated itself from other forms with its emphasis on one’s spiritual nature, an acceptance of the mystery of human existence, and a recognition that innovation must be tied to existing traditions and customs. He was opposed to the rationalism and free-market doctrinarism of libertarians and the nationalist imperial ambitions of neoconservatives. Kirk believed, instead, that one had to resort to the “moral imagination,” one’s spiritual and creative powers, to discover ordered liberty within oneself and for society. Although his type of conservatism does not reside in the corridors of power today, it still resonates in the works of scholars and the public and may provide a path forward for the conservative movement in the future.

Notes

[1] I would to thank the McConnell Center at the University of Louisville for sponsoring a panel related to this symposium at the 2018 American Political Science Conference and Zachary German for his constructive comments on these papers. I also would like to thank Richard Avramenko with the Center for the Study of Liberal Democracy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Saginaw Valley State University for supporting my sabbatical, which enabled me to write this article and organize this symposium for Humanitas.

[2] For more about the biography of Russell Kirk, see James E. Person Jr., Russell Kirk: A Critical Biography of a Conservative Mind (Lanham, MD: Madison Books, 1999); John M. Pafford, Russell Kirk (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), and Bradley J. Birzer, Russell Kirk: American Conservative (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2015).

[3] Russell Kirk, Randolph of Roanoke: A Study in Conservative Thought (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1951).

[4] Russell Kirk, The Conservative Mind (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1953). For more about the reception of the book, see Henry Regnery, “Russell Kirk and the Making of the Conservative Mind,” Modern Age 21.4 (Fall 1977): 338-53; W. Wesley McDonald, Russell Kirk and the Age of Ideology (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2004), 21-33; Birzer, Russell Kirk: American Conservative, 110-20.

[5] For more, see Charles C. Brown’s Russell Kirk: A Bibliography (Wilmington, Del.: ISI Books, 2011).

[6] Russell Kirk, “What is Conservatism?” The Portable Conservative Reader (New York: Penguin Books, 1982), xiv.

[7] Russell Kirk, “Ten Conservative Principles” in The Politics of Prudence (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 1993), 15-29.

[8] Russell Kirk, “The Moral Imagination” in Literature and Belief Volume I, 37; also see Enemies of the Permanent Things: Observations and Abnormity in Literature and Politics (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1969), 39-41, 48-49; W. Wesley McDonald, “Reason, Natural Law, and Moral Imagination in the Thought of Russell Kirk,” Modern Age 27.1 (Winter 1983): 15-24.

[9] Russell Kirk, Decadence and Renewal in the Higher Learning: An Episodic History of American University and College Since 1953 (South Bend: Gateway Editions, 1978), 260; Enemies of Permanent Things, 28, 39-41, 47; “Can Virtue Be Taught?” in The Wise Men Know What Wicked Things are Written on the Sky (Washington D.C.: Regnery Publishing, 1987), 68-69; Eliot and His Age: T.S. Eliot’s Moral Imagination in the Twentieth Century (Peru, IL: Sherwood Sugden and Company, 1988), 47; also see Mark Henrie, “Russell Kirk and the Conservative Heart,” Intercollegiate Review 38.2 (Spring 2003): 20-21.

[10] Kirk, Enemies of Permanent Things, 20, 39-43; The Roots of American Order (Washington D.C.: Regnery Publishing, 1991), 22-38, 43, 109-113.

[11] W. Wesley McDonald, Russell Kirk and the Age of Ideology, 62-65; also see Russell Kirk, Edmund Burke: A Genius Reconsidered (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1967). For a criticism of Kirk’s understanding of Burke, see Seth Vannatta, “Pragmatic Conservatism: A Defense,” Humanitas XXV.1/2 (2012): 20-42.

[12] Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France, Conor Cruise O’Brien, ed. (New York: Penguin Books, 2004), 169-74. For more about imagination in Burke’s writings, see David Bromwich, Moral Imagination: Essays (Princeton: Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2014).

[13] Burke, Reflections, 169-74, 183-84, 194-97; Kirk, The Conservative Mind, 12-70; also see Peter J. Stanlis, “Edmund Burke, The Perennial Political Philosopher,” Modern Age 26.3/4 (Summer/Fall 1982): 326-27; McDonald Russell Kirk and the Age of Ideology, 98-106.

[14] Irving Babbitt, Rousseau and Romanticism (New York: Meridian Books, 1959) and Democracy and Leadership (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 1979); also see Claes G. Ryn, “The Humanism of Babbitt Revisited,” Modern Age 21.3 (Summer 1977): 251-62; “Babbitt and the Problem of Reality,” Modern Age 28 2/3 (Spring/Summer 1984): 156-68; Will, Imagination, and Reason: Babbitt, Croce and the Problem of Reality (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1997).

[15] Babbitt, Rousseau and Romanticism, 44, 137; Kirk, “The Moral Imagination,” 38; also see McDonald, Russell Kirk and the Age of Ideology, 43; Gerald J. Russello, The Postmodern Imagination of Russell Kirk (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2007), 55-57.

[16] Russell Kirk, “May the Rising Generation Redeem the Time” in The Politics of Prudence (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 1993), 287.

[17] For more about Kirk’s account of the “moral imagination” and its contributions to conservative thought, see John Fairley, “Russell Kirk and the Moral Imagination,” Dissertation Submitted to Macquarie University, Sydney, September 2015.

[18] Russell Kirk, The American Cause (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2006), 2.

[19] Russell Kirk, Prospects for Conservatives (Washington D.C.: Regnery, 1989), 6; Enemies of Permanent Things, 154; The American Cause, 2.

[20] Kirk, The Conservative Mind, 44; Russell Kirk, A Program for Conservatives (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1962), 4, 41.

[21] Russell Kirk, “What Are American Traditions?” Georgia Review 9 (Fall 1955): 283-89. For an account of the debate concerning Kirk’s conception of tradition among conservative thinkers during his time, see McDonald, Russell Kirk and the Age of Ideology, 86-95.

[22] Kirk, Enemies of Permanent Things, 181. For a different perspective on nostalgia, Andrew R. Murphy, “Longing, Nostalgia, and Golden Age Politics: The American Jeremiad and the Power of the Past,” Perspective on Politics 7.1 (March 2009): 125-41; Samuel Goldman, “The Legitimacy of Nostalgia,” Perspectives on Political Science 45.4 (2015): 211-14.

[23] Kirk, A Program for Conservatives, 305.

[24] Kirk, Enemies of the Permanent Things, 61; Kirk, The Conservative Mind, 142-43. For more about the influence of T.S. Eliot on Kirk’s understanding of the “permanent things,” see Birzer, Russell Kirk, 217-18.

[25] Kirk, Enemies of the Permanent Things, 287; Kirk, The Roots of American Root, 83, 464-66.

[26] Kirk, The Conservative Mind, 23, 35.

[27] Michael Federici, “The Politics of Prescription: Kirk’s Fifth Canon of Conservative Thought,” Political Science Reviewer 35.1 (2006): 159-78; Ted V. McAllister, “The Particular and the Universal: Kirk’s Second Canon,” Political Science Reviewer 35.1 (2006): 179-99.

[28] Kirk, Enemies of the Permanent Things, 254, 287; The American Cause, 52-71; also see Bradley J. Birzer, “More than ‘Irritable Mental Gestures’: Russell Kirk’s Challenge to Liberalism, 1950-1960,” Humantias XXI.1/2 (2008): 64-86. Kirk also criticized libertarianism, along with Marxism and liberalism. For more, see McDonald, Russell Kirk and the Age of Ideology, 153-63.

[29] Kirk, Enemies of Permanent Things, 98; The Conservative Mind, 367-74.

[30] Kirk, A Program for Conservatives, 102-5.

[31] Ibid., 64. For more about the problem of positivism, see Lee Trepanier, “The Recovery of Science in Eric Voegelin’s Thought” in Technology, Science, and Democracy, Lee Trepanier, ed. (Cedar City, UT: Southern Utah University Press, 2008), 44-54.

[32] Russell Kirk, “A Conscript of Education,” South Atlantic Quarterly 44 (January 1945): 82-90; also see Academic Freedom: An Essay in Definition (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1955); Decadence and Renewal in Higher Learning; The Intemperate Professor: And Other Cultural Splenetics (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1956). For more about the challenges confronting higher education today, see Lee Trepanier, ed., Why the Humanities Matter Today: In Defense of Liberal Education (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2017).

[33] Kirk, Decadence, 247-61. These dogmas were from C.S. Lewis’ The Abolition of Man, which Kirk acknowledged.

[34] Ibid., 302-7; 334-35.

[35] For more about these differing features of conservatism, see W. Wesley McDonald, “Russell Kirk and the Prospects for Conservatism,” Humanitas XXI.1 (1999): 56-76; McDonald, Russell Kirk and the Age of Ideology, 153-63, 204-19; Paul Edward Gottfried, Conservatism in America: Making Sense of the American Right (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 8-58.

[36] An excellent example of this is Russello, The Postmodern Imagination of Russell Kirk.

[37] For example, Modern Age devoted its 2017 spring issue to “Being Conservative in the Year of Trump” (59.2: 11-74) and its 2018 spring issue to “Conservatism and Liberalism Beyond Trump” (60.2: 7-60). For more fundamental problems with the conservative movement, see Claes G. Ryn, “Debacle: The Conservative Movement in Chapter Eleven,” Humanitas XXI.1/2 (2008): 5-7.

[38] Charles Murray, Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010 (New York: Crown Forum, 2013); Robert D. Putnam, Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015); Lee Trepanier, “The Resentful Politics of Populism,” VoegelinView July 20, 2018. Available at https://voegelinview.com/the-resentful-politics-of-populism/; F. H. Buckley, “Conservatism: Trump and Beyond,” Modern Age 60.2 (Spring 2018): 7-15.

[39] For more about this discussion, see Modern Age 59.2 (Spring 2017). This possible return to a Kirkean conservatism as a way forward was predicted by McDonald, “Russell Kirk and the Prospects for Conservatism.”

This was originally published in Humanitias.