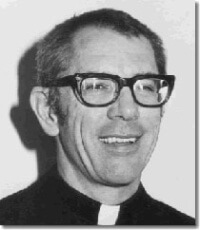

Remembering James Schall, S.J.

James Schall was a great teacher. He had a natural ability to connect with everyone he met, especially the students who were readily drawn into his own excitement of learning. A conversation with Jim Schall was always a lively event. You never knew where it was going to lead, as he was capable of leaping across great intellectual chasms. That was simply his style. It came through very effectively in his writing in multiple genres, but most of all in the essays large and small that he poured forth. You knew right away you were in touch with a mind in full flight. Discussions were animated, and enlivened with bursts of humor and great fun. He introduced us all to “another sort of learning.” It was no wonder that his Socratic style of teaching had such enormous impact on generations of students.

Yet no matter how elevated the topic, the conversation never eclipsed the particular persons involved. Jim Schall was always first and foremost interested in you and he made it a point to remember what you said. He would always inquire again how various members of the family were doing the next time you met. More than a skill of social memory, this arose naturally for someone who always placed the conversation partner first. Jim Schall really cared about what was happening to you and in your world. We were in touch at a deeper level than the viewpoints we exchanged on politics or sports or metaphysics. He could move easily from the most superficial to the most profound without skipping a beat, for he held it all in his wide understanding of life and the world. His grasp of things was a marvel to behold and he was ready to share it with whoever happened to be at his side.

When we ask how Jim came by this prodigious comprehension of things personal, philosophical, and ecclesiastical, we are thrown back on what he called “the mind that is Catholic” in one of his titles. Jim Schall was the living embodiment of a truly catholic mind that always reaches toward the whole. A life time of learning was ready to hand when the issues of the day arose and he was glad to impart it to all who would journey with him. The secret of the agility that remained with him up to the very end lay in Jim’s capacity to order everything in relation to its source. Contrary to our picture of knowledge as a jumble of information, the only really useful understanding is one that has sought to grasp the world as a whole. This requires, as Jim knew, a willingness to go beyond the world, if we are to see it as it really is. His mind stretched toward the mind of God. That was the great principle he had learned from St. Thomas and from the Catholic tradition that had long sought to bring reason and revelation together.

How Schall embarked on a project of such formidable scope, one that was nothing less than a contemporary repetition of the Thomistic synthesis, is itself one of the most notable aspects of his life. And no doubt it is among the least well understood by us who were simply pleased to call him our friend. Yet even as friends, perhaps especially as friends, we owe it to him to try to understand something of the architectural girding of his mind. His capacity to draw on a vast range of historical, philosophical, literary, and theological materials, without being an expert in any of those fields, is surely astonishing. The secret, as Jim readily explained, is that he worked in a field that touched on all of them and therefore provided the possibility of holding them all in a coherent whole. That is the nature of political theory. Without becoming expert in any of the fields it contemplates, political theory gains sufficient depth to be able to place them in relation to one another. It is the essence of liberal learning, as it is of the knowledge that practical statesmen must call on in acting with regard to the whole.

Schall’s first impetus toward the contemporary revitalization of political theory came by way of his studies with Heinrich Rommen and the natural law revival promoted by Maritain, Gilson, Simon and others. But what really enlarged his horizons, beyond this largely Thomistic framework, was his encounter with the work of the great German emigres, especially Strauss and Voegelin, who opened up the depths of classical thought and the sweep of the history of political ideas. In many respects Jim Schall was a collaborator and a disseminator of this extraordinary rebirth of political philosophy that has retained its momentum into the present. At a time when the humanistic disciplines were taking refuge in historical and philological rigor, and the social sciences were lost in a methodological desert from which they have not yet returned, political theory was raising the enduring questions from which every society must eventually take its point of reference. Jim Schall understood himself to be part of this contemporary intellectual renaissance, even if it has generally slipped below the radar of public notice.

Jim’s own significant contribution to this great project of renewal was to remind us of the distinctly Catholic underpinning by which it might be sustained. He grasped as few of his political theory colleagues did, the distinctively Catholic nature of thought at its very best. Schall knew and appreciated the openness to revelation evinced by the great European rediscoverers of political theory, but he also knew of their limitations in this regard. At best Strauss made room for revelation, while Voegelin opened toward it without it fully embracing it. Only the Catholic mind, especially one familiar with the example of St. Thomas, could find the balance between reason and revelation that would do justice to each. Neither belonging wholly to this life, nor looking only toward the next one, it was the Catholic viewpoint that could teach responsibility for the world without becoming absorbed in it. Reason, Schall knew, could not long endure unless it was anchored in that which is beyond it.

Certainly this was a large civilizational perspective that was well reflected in the pontificates of John Paul II and Benedict XVI. It was especially with the “Regensburg Address,” where Benedict put Christianity firmly on the side of reason, that he was particularly taken. It was one of the great pleasures of my life to be able to spend time with Jim Schall in those years when we could contemplate such a remarkably capacious Catholic moment in our own day. In retrospect we realize that it is the nature of all such moments that they too pass. Yet we hold onto the memory and we hold our friend in memory. We know that we have been privileged to catch a glimpse of that long dinner party that, unlike our fleeting ones perched on the edge of the Chesapeake, are destined to endure beyond time. Friendship is among the inestimable blessings we receive in this life, and I count myself privileged to have been able to count Jim Schall among my friends. But I would be remiss in my obligations to friendship if I did not also thank our mutual friend, and student, Cindy Searcy for making it possible for friends to do what Aristotle counted as the mark of friendship: spending time together. Deo Gratias.