Review of The Coen Brothers and the Comedy of Democracy

The Coen Brothers and The Comedy of Democracy. Sara MacDonald and Barry Craig. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2018.

This is both a thoughtful book and a light-hearted one—not very big (about 100 pages of text) and modest in its goals. Authors MacDonald and Craig present their main theses in a helpful Preface and Introduction. First, the movies of Joel and Ethan Coen might have serious teachings, even if they are produced primarily for entertainment. Second, while the tragic or grim movies by the brothers may present a bleak view of how it is necessary to go on somehow in a meaningless world where evil is likely to triumph, the comedies have something different to say. Third, these authors are confident that the Coen brothers suggest in a number of comedies that modern liberal democracy is the best possible regime for human beings. In addition to sharing in the enjoyment of a number of movies, the book offers reflections that are relevant to political philosophy, and can stimulate further thought.[1]

The kind of comedy they claim to be explicating is one of justice realized, in a world that is very familiar to us. Many of the apparent frustrations of human life can be and are resolved by skillful or successful comedy—as it was, for example, by Aristophanes, and as has been explicated by Hegel. Above all, the appearance that different noble or desirable things might be incompatible, or the achievement of one might occur only by the sacrifice of others, is reconciled or—let us say the word—synthesized by a kind of rational process that goes beyond the rationality of any one person. For Hegel, as presented by our authors, comedy achieves or articulates a perspective that is superior to that of tragedy. A tragic hero mistakes a part of human existence for the whole; a revelation of the partiality of the merely partial is shattering. A comic hero, on the other hand, finds his or her way from a part at least some distance toward the whole. Comic writers are able to discover how history can transcend and reconcile conflicts in human life, and then convey that transcendence to an audience. The greatest transcendence is found in a political regime—liberal democracy–in which individuals are free to pursue their rights, with economic rights at the core. It would not be surprising to find selfishness, crime, and violence; but it is people’s freedom—and perhaps only their freedom—that allows them to discover both rationality and love, including the love of friends and a family.

It might be worth pausing here to consider whether it is realistic to try to learn something from movies. The authors say that in their own teaching they make use of contemporary authors as well as the classics, but film and television also have a place in the classroom. “It is clear that film is a contemporary art form that is able to contribute to the exploration of [the most important] questions. It is also clear that great films can hold their own alongside great books.” At the risk of rudeness, one might suggest that we had better hope so; the twentieth century probably produced more memorable movies than memorable books, and it seems increasingly unlikely that books written in our time will be remembered as classics. If movies do not bring us wisdom, where are we to turn for such a gift?

We are familiar with the notion of “escapism,” and in some cases there is a sense of a temporary escape from the real world to a more fantastic or unlikely one, after which we, along with characters in a movie, return to the real world having learned certain lessons. In the example of romantic comedy that the authors borrow from Hegel, issues between lovers that might seem irreconcilable (family feuds, previous or rival love affairs) prove not to be irreconcilable after all when they are seen from a very different perspective. With tragedy there is the somewhat different notion of “catharsis,” borrowed to some extent from Aristotle. Characters who may be greater or more heroic than most of us (although modern genres, including the novel, tend to focus on ordinary people) struggle with fates that cannot be changed, and may be too much for anyone. We are taught, as it were, to reconcile ourselves to more ordinary lives with more ordinary struggles.

Politically speaking, tragedy may be more “conservative,” while comedy may be more hopeful or reformist. In the language of Barack Obama, someone who can see the possibility of reconciliation between apparently opposed positions may be a uniter rather than a divider, and may find a way to a political solution that reflects a greater unity. Tragedy may make us skeptical of human solutions to apparently intractable—or natural—problems. On the other hand, comedy may open us to utopianism, including the possibility of fanatical efforts to re-shape humanity so that we can avoid repeating the mistakes of the past; tragedy may encourage not only realism but defeatism or even nihilism, which may open us to radical violence in a different way.[2]

“Raising Arizona” (1987) and “Fargo” (1996, action in 1987)

The first comedy our authors deal with is “Raising Arizona.” A habitual criminal (H.I. or Hi), who has already spent substantial time in prison for non-violent robberies, falls in love with a police officer (Edwina or Ed)—the one who has repeatedly taken his picture as part of the intake process in jail. She returns his love, on the condition that he give up a life of crime. The early plot twist, generating a series of crises which ultimately have to be resolved, is that the newlyweds resolve to have a child, and discover that it will not be possible for them to have a biological child together. The news is full of a story about a furniture tycoon and his wife giving birth, with some kind of assisted fertility, to quintuplets. Ed, supposedly the sworn defender of both the law and the Constitution, proposes that they kidnap a baby, with the excuse that the parents of five will still have four, and who knows, the one who is kidnapped may receive better care this way. Ultimately they return the baby, and make a deeper resolution than ever to live patiently, according to the law, still hoping to have a child one day. Their best hope is to leave Arizona, their home state. (The fact that Hi has a record in Arizona prevents them from adopting legally there). The worst criminals in the movie either return voluntarily to prison, or get killed in a way that would have been difficult to plan; there are elements of sheer good luck in the resolutions achieved in the movie.

For MacDonald and Craig, the lessons seem to be that the older Arizona of frontier days, where it might have been necessary to deviate from the law to get ahead, and indeed a certain kind of violent cowboy might be a hero, is being replaced by a new, more peaceful and lawful Arizona. The change is for the better, and it meets deep human needs, including the need for love and family. One might think the love of a baby is about the easiest kind available (although “undemanding” would not be the right word for the tasks of caregiving); literally everyone who meets “baby Arizona” falls in love with him. The movie is set firmly in the Reagan years, as well as in a specific state that voted repeatedly for Reagan, and there are certainly questions about whether unbridled capitalism, such as in the cut-rate furniture business, is necessarily morally superior to crime. (There are clear suggestions that successful capitalists can be as nasty as criminals, but they are typically smarter).

If Reagan stood for the defense of “free markets” as opposed to government regulation, this might be seen as somewhat questionable; but the “social conservatism” of the Reagan years probably fares better. Not only are there repeated suggestions that parenthood might redeem bad or questionable people; but there are strong hints that the main reason people turn out bad is that they have bad childhoods—something responsible adults might do something about. (There is very little suggestion in the movie that government programs of any kind are of much help in the raising of children). In a way the protagonists discover and explore nature; with a newborn baby, we might say nature is unchanged, uncorrected or unspoiled. What makes a baby lovable is that almost every aspect of his or her life remains merely potential; adults can read any hope they like into the child’s future. Nature at its best or friendliest shows the potential of possibilities that are yet to be explored, and freedom from brutal realities that are yet to be discovered. But the protagonists also learn through law, civilization, and history, any of which might be somewhat different from nature. A society can prove itself as a good provider of human satisfactions, which are all the sweeter and more lasting if chosen freely; some societies are better than others; and the improvement is probably revealed through history, with the new generally better than the old.

MacDonald and Craig argue that it is the family as explored by John Locke that we find celebrated in this movie. Somewhat engagingly, our authors point out that “Locke, while not a writer of comedy, was one of the philosophic inspirations of the American founding.” As they say, Locke insists that the authority of parents over children is less than had been believed traditionally; parents only have the power they need to ensure that children grow up to be “useful.” While the authority of parents is treated as quite distinct from that of governments, our authors point out a similarity: “As parents are naturally guided by their inclinations to care for and educate their children, so governments should be rationally guided by the same protective concerns—seeking to ensure the safety of their citizens’s lives, liberties, and properties.” There is a similarity between “love between parents and children” and “justice within political communities.” Somehow Locke describes us as having both rights and obligations, with rights being more fundamental. There is an obligation “to care for one’s own children and others,” as much as possible, “when [one’s own] preservation comes not in competition.”[3]

It is very American to think that if one ventures down the road of a modern liberal understanding of things, there is a reasonable chance you end up at some of the better Disney movies: taking care of oneself; enjoying the success of others in a live-and-let-live kind of way; remaining skeptical of the claims of any individual to having authority over another. The family can become a group that one can count on for warmth and support, if not for the intense closeness and necessary discipline of the pre-democratic or traditional family. It is reasonable to find the so-called nuclear family, in which it is fairly easy to like each other, rather than a larger extended family which is more likely to include some stinkers. Tocqueville describes democratic American families in action as long ago as the 1830s; he says it is so pleasant for parents to see their children as friends and (eventually) as equals that people who grew up in a more aristocratic world can immediately be won over to the new one based on the joys of family life. There will be many economic and other ties to people outside the family, in a world that can be harshly competitive; the “new” family can provide at least a conditional “haven” (to borrow from Christopher Lasch) in such a world.

The emphasis on the American family raises questions. There is a freedom from some of the obligations of the past, but how far does that freedom go, and what are the real limits on it? It may be tendentious to go on about this at greater length than MacDonald and Craig do, but it is part of giving credit to the Coen brothers to see the issues that are raised in their work. Locke addressed traditional views linking the patriarchal family to politics, and the authority of political rulers. In Locke’s time and place, the traditional arguments, to understate the case, were rooted in the Bible, and Locke strengthens his own case by often appealing to the text of the Bible, and showing that his most prominent opponents, such as Robert Filmer, make mistakes in interpreting the sacred text. Ultimately, however, albeit in passages that may be difficult to find, and easy to forget, Locke shows that a careful reading of the Bible reveals views for the guidance of human life that Locke himself rejects.[4] He is not simply opposed to this or that “conservative” interpreter of the Bible, who may be eccentric or unreliable, but to the tradition as a whole insofar as it contradicts what he takes to be the teachings of reason.[5] One remarkable result of Locke’s careful approach is that it is possible for well-meaning people to accept most if not all of Locke’s teachings while providing them with at least some support from extensive quotations from the Bible. The American regime, at least until the 1960s, provided plenty of examples. Part of the humour of “Raising Arizona” is the idiosyncratic diction of the characters, redolent of the Bible among other sources, differing slightly even from one character to another. Of course when one speaks of the respect in which the Bible is held, or was formerly held, in the U.S., one must also speak of the vast variety of religious denominations that are found there. Idiosyncrasy and individualism are valued as expressions, to some extent, of personal choice and interest.

Surely the ongoing appeal of the Bible is partly that it supports the notion that we have obligations that are separate from, always potentially opposed to, our own self-interest, and in this light, such obligations are to some degree beyond question. As long as people read the Bible, they may have difficulty in trying to shake the idea that no matter how free we feel ourselves to be, there is such a thing as divine punishment. Does Locke in all his diligent searching find any such obligations as the Bible describes, other than the “obligation” to protect our own rights, above all the right of self-preservation? According to Locke, for example, the fact that humans have a desire for copulation, and this desire is not directly related, as far as we can tell from our experience, to any thought about children, is something we can know with confidence whether the Bible says so or not.[6] There is plenty of evidence that if adults are not taught to be reasonable, they are likely to be indifferent or cruel to their own children; telling fathers that they are authority figures may lessen the indifference, but is less likely to lessen the cruelty.

Locke appeals to the fact that people may come to want children, and this desire might be rational, or might be made more rational than it would otherwise be, if it is a matter of wanting to preserve or continue oneself. The individual making such decisions does not do so as part of some non-political or pre-political “whole,” such as a patriarchal family, but as a rational individual. Having children is often good, for example, in that one may need allies in life in the medium to longer term, and some short-term sacrifice can make this possible. (Warm relationships, or actually getting along, may be a kind of bonus, based on mutual respect for each other’s rights). The relationship between parents and children has so much to do with personal security and economics, and so little to do with biology or even love, that any adult can easily become a parent in every sense that a biological parent can ever be.[7] “By interpreting the concern for children in terms of the strongest and most stable human desire, that of self-preservation, Locke provides the basis for a relatively lasting connection between fathers [and mothers] and their children without giving fathers the great powers patriarchalism thought necessary.”[8] Obedience, including the obedience of children to their parents, is “not the biblical virtue [expressed in the Fifth Commandment and in many other passages] but a temporary necessity [owing, for example, to a child’s weakness].” Whether parents deserve or can reasonably expect any honor or respect from any grown children depends on material circumstances: how they have treated the children in the past; whether there is an inheritance to provide an incentive for good behavior; whether parents have actually done, or are likely to do, more for “their” children than say an employer or some stranger has done.[9]

Locke suggests that parents must do what they can to ensure children are “useful to themselves”; there may be an ambiguity as to whether this means useful to the parents, or to the children themselves, or to both. Locke distinguishes himself from the Bible by saying he is opposed to conceding that any parent morally has the power of life or death over a child; among other reasons, a dead child can hardly be useful. What about less severe forms of discipline? Of course from an early age a child can store memories of mistreatment, and act accordingly, if only by running away and becoming “useless” to the abuser; Locke suggests more than once that a child can go to work for money, “shift for himself,” at a younger age than some people might expect. Rightly or wrongly, many middle-class people today protect children from the workforce in order to ensure more education, and higher lifetime earnings. Locke seems confident that with his emphasis on economic security, as the basis for increasing prosperity, his approach is consistent with, and probably supports, substantial growth in population. One might borrow language from our own age and say his arguments as a whole are pro-natalist rather than anti-natalist.[10]

When things go well between parents and children, and the constraints that applied to a father who was a powerful authority figure are gone, there may be more opportunities to relax and enjoy family life in a spirit of genuine affection. The great advantage of starting with a baby, whether biologically one’s own or someone else’s, is of course that the child can be socialized to a specific family, and adopt the manners and habits that are attractive in that context. Some parents or “parents” in “Raising Arizona” believe strongly in following the teachings of Dr. Spock on the care of babies—or at least they believe in the virtue of having a copy of the book. Despite this sense that there is a reliable text produced by an expert, the actual child-rearing we see, even among more or less decent people, varies considerably.[11] Freedom on the part of parents obviously does not guarantee a good outcome for children; yet the movie seems to take the view that freedom is so good in itself that it argues against any agency trying to micro-manage such matters. Various people have at least a brief opportunity to try being “parents” to baby Arizona (there are several actual and attempted kidnappings); all except the original or birth parents seem worse (their actions subject the baby to extreme danger), and the movie poetically has Hi and Ed return the baby to those parents. There is some reason to wonder whether the original Arizona parents are likely to be great parents. Hi hopes to get the reward money that has been offered—surely an extreme example of chutzpah—but it is Ed (not, as our authors suggest, both lovebirds) who say it is not right to be thinking of getting something for themselves.

How free are Lockean individuals? Many things that we think of as becoming common only after World War II, and perhaps more common in the U.S. than elsewhere, are anticipated in Locke: the use of birth control to ensure that sex can be rationally separated from procreation, and procreation can be planned; liberal divorce to ensure that adults can live in arrangements that they find convenient—including, presumably, arrangements for custody and visiting of minor children; in vitro fertilization and other methods to ensure that people who want children can have them.[12] “The primary purpose of Lockean law is to resolve controversies and to protect the property and lives of citizens from the violence of others. It is not primarily intended to foster a particular way of life [Biblical or otherwise], but to be a neutral umpire which leaves each individual as free as possible to follow his own will in disposing of his person, actions, and possessions.”[13] From such freedom, “Raising Arizona” as interpreted by MacDonald and Craig implies, can come true human happiness.

“Fargo,” like “Arizona,” is set in the Reagan years, and there are parallels between the two movies. There is both crime and punishment, not always according to law, in both movies. There is family life, and love. As in “Arizona,” in “Fargo” there is a baby somehow at the center of the action—in this case, the child that Marge the chief of police is expecting, still in utero as she continues to work late in her pregnancy. In “Fargo” there is a sharper divide between the good people and the bad people; the bad are truly evil, and the good do not seem to need to struggle much to remain good. “Fargo” seems to make a clearer or easier case for avoiding a life of crime. There is a weak individual at the start of the movie’s action, Jerry Lundegaard, more or less unsuccessful in a job which he has been given as a family favor. He has somehow come to owe a million dollars, presumably to criminals, so he decides to “fake” his wife’s kidnapping in order to get the money from his wealthy father-in-law, Wade Gustafson. Extreme violence ensues.

Wade the father-in-law is among the quiet, decent, probably scrupulously law-abiding “Minnesotans” in the movie; he is also avaricious and penny pinching (but perhaps not as mean as Nathan Arizona the father of quintuplets). In a way Wade’s refusal of a loan to Jerry is also part of what precipitates the violence, including his own death. There is supposed to be an understanding that no one will get hurt in connection with the fake kidnapping; instead seven murders unfold, the most grisly of which has made “wood chipper” into a part of popular culture. Of the two criminals who are hired for the job, one is much more habituated to violence than the other, and he sets the tone for the criminal part of the movie. Against all this brutal and somewhat horrifying crime, we have a police officer (Marge) who can fairly be described as dull and dutiful, female and visibly pregnant, solving the case (although realistically she is entirely too late for the seven victims), when she is not chatting about mundane matters with her husband Norm.

In the case of “Arizona,” MacDonald and Craig are somewhat opposed to various commentators in that they are sure there are serious teachings to be found in this very fun movie. In the case of “Fargo,” there is a much more specific disagreement between critics in general and our authors.

Reviewers have commented on the “cheesy Norman Rockwellian” setting as well as the emptiness of the American Dream depicted in the course of the film. The Coens encourage this somewhat cynical reading of middle America … While critics focus on the financial and moral bankruptcy of Jerry Lundegaard and the criminals he hires, their derision for the majority of the people in the heartland, represented by Marge and her husband Norm, means that they miss the essentially hopeful vein of the film . . . At the end of Fargo, justice and love have prevailed, and Marge’s unfaltering devotion to both details an account of how love can be the foundation of justice even when faced with the most heinous of crimes. (24)

It is simply not clear that Marge and Norm can bear the weight of this analysis; in some ways there is less to them than there is to Hi and Ed in “Arizona.” Our authors begin their chapter on “Fargo” with a silly knock-knock joke between Marge and Norm. The sense is that Norm is slower on the uptake than Marge, but she enjoys speaking at his level and enjoying what he so obviously enjoys. Norm is an artist, possibly specializing in painted duck decoys that are both beautiful and practical for his Minnesota neighbors. In the course of the movie he finds out that a painting of his—a painting of a duck decoy–is going to be used on “the three cent stamp,” and Marge quietly celebrates with him. In their expectation of their child (if they are excited, they hide it well), Marge and hubby seem to have become somewhat infantile themselves.

As for the struggle against injustice, Marge’s sense of duty cannot be questioned—indeed many viewers will wonder if she should be driving around, checking crime scenes, at her advanced stage of pregnancy. One can see how she has been promoted to chief of police in this small-town police force; she is likely to be the brightest person on the force, and indeed one of the brightest people in town. There is still a question, however, whether she tends to assume not only that “most folks are good,” and these violent criminals from “outside” are the exception, but indeed that the people she sees every day, people like Jerry, cannot possibly be criminals. (The two criminals are hired in Fargo, North Dakota, just across the state line and therefore technically “outside” Minnesota where the “good” protagonists all live.)

Reviewers have speculated on why an interlude between Marge and Mike Yanagita, an old high school classmate, is included in the movie. Mike makes clear he has romantic thoughts about Marge. Marge may have had similar thoughts, at least at the back of her mind; she goes on a kind of date with him, and fixes herself up for it. Surely many of us would like to believe the unlikely proposition that we are approximately as attractive as we were in high school. Marge eventually lets Mike know there is nothing doing; Mike cries and asks for her sympathy, saying his wife has died. (He may have been suggesting Marge would commit adultery, but supposedly he wasn’t going to do so himself). Later Marge discovers that Mike lied; his wife is still alive. Some suggest this explains the presence of the interlude; from the discovery of Mike’s dishonesty, Marge is able to re-consider the question whether Jerry has lied, and this allows her to unravel the case. Without knowing why the Coens included the “Mike” interlude, it is remarkable to suggest that a detective wouldn’t think one of her neighbors might lie until she is forced to recognize that another has done so. She has been living in a fairy land—or she has been foolishly believing that to be the case—and she has to be shocked into a recognition that ordinary Minnesotans might lie, to say nothing of committing serious crimes.

In their chapter on “Arizona” MacDonald and Craig refer to the thought of John Locke. In the chapter on “Fargo” they discuss Plato’s Republic at some length. Socrates warns that poets and other artists have a tendency to use their art for deception—either to present what is real in a deceptive way, so that the consequences of bad actions, for example, are minimized or romanticized; or to abandon what is real, and encourage people to give up on reason in favor of living in a fantasy. Socrates, at least as presented by the fantastically poetic Plato, is more than willing to beat the poets at their own game—to use art to reinforce the search for truth, rather than short-circuit such a search. If the truth comes to appear harsh or disappointing, a more edifying picture of the truth, not one that is fundamentally misleading, might be presented in order to encourage the search even in what seem to be difficult times. The Coens, according to our authors, show their willingness and determination to use art, sometimes deceptively, to encourage truth and justice, not to undermine these goals. The other theme our authors draw on from the Republic is that of the tyrannical life as opposed to the just life. The tyrant is controlled by passion rather than reason; the proof of this is in the irrational extremes to which he will go in order to achieve short-term benefits for himself: turning on friends and family, using violence somewhat indiscriminately, and so on. The Coens, say our authors, follow Plato in using art on the side of good people and justice, in opposition to bad people and injustice.

Perhaps we can borrow from Nietzsche and say there is too much interpretation here, not enough text. The only powerful motivation that seems to be at work in “Fargo” is money, probably combined with a certain amount of recognition or respect. Jerry wants to be a big shot, like his wealthy father in law–who has earned his money. Jerry’s debts spur him to become a criminal, and the criminals he hires are familiar with doing bad things for money—sometimes even for small amounts of money. It is probably rational to avoid a nomadic, unsettled life of crime, in which every big fish criminal can be swallowed by a bigger fish; does that mean it is rational—the best we can hope for—to live the dull, quotidian, mundane, anodyne life of the bourgeois? A life in which Marge, a police detective, has sunk into a kind of cheerful, bland ignorance of human nature? Granted, there is a similarity to some great detective stories, such as the Maigret stories by Simenon. The detective has a much duller life than many criminals, he works in a sometimes pedestrian way at a routine, lacking in glamour (of course successful criminals also benefit from a careful, methodical approach to their crimes); and in his bureaucratic life, he is often denied the recognition he deserves, and is forced to deal with politicians or dullards. The love of his wife, and domestic tranquility of his home, along with apparently endless varieties of French cuisine, are all great comforts. Yet the underlying joke is always that Maigret is a student of human nature, and crime in its many guises (often non-violent) allows him to learn a great deal, while Simenon shares knowledge with the reader. Does Marge learn anything in the course of “Fargo,” or does she simply prove, predictably enough, that Marge is always Marge, and in some important ways this will be good enough?

If we are to refer to the Republic in understanding “Fargo,” MacDonald and Craig come close to suggesting that everything would be great if only we could get back to the “healthy city,” perhaps the first city we see in the Republic, in which everyone works hard on specialized tasks, and looks forward to a good night’s sleep every night. There is limited recreation, perhaps a hymn or two after a meal and before bed, and sex only with a view to reproduction. There seems to be no art to speak of, no ambition, and none of the arguably noble or good things, other than money, that might excite or stimulate such promising yet dangerous aspects of the human soul.[14] To be even nastier, we might say the “good” side of small-town Minnesota in “Fargo” reminds us of Nietzsche’s last man: not only clinging to simple comforts, but more and more inclined to believe that these are enough—it is a relief to be rid of those great, sometimes terrible passions of the past.[15]

If we compare “Fargo” to “Arizona,” there simply seems to be a richer presentation of human psychology in the latter movie. What makes H.I. go straight in the end? First, probably, he will follow Ed’s lead. He followed her into accepting normal domestic life, he followed her into taking the child, and he follows her into giving the child back. Secondly, he is not as young as he used to be, and the violent chaos that has come upon them has probably been a bit shocking; his ex-con friends beat him, tie him up, and take the baby. Twice he is the rabbit in a long violent chase, involving bullets whistling around him and dogs chasing him, as a result of trying to steal a large bag of diapers. For a while a bag of diapers (or even two bags) is the McGuffin in the movie. (If you enjoy movie comedies, you will enjoy this one). The criminals are becoming more violent than he remembers, but so are the police and even neighborhood dogs.

There is a third fact which is lurid, larger than life, and up to a point unique to him, which probably points H.I. toward returning the baby, and giving up crime altogether. He has imagined a kind of monster or ogre in human form, who brings destruction wherever he goes, hunting him down as a punishment for the wrong he has done in taking the child. As frightening as the more or less realistic events in the movie are, he is terrified of even more gruesome horrors that might be inflicted on him by this avenging monster. It turns out there really is a monster—a man on a Harley named Leonard Smalls; he doesn’t seek revenge, but he does capture people for whom there is a reward, or simply people like babies who have significant value on the black market. He is in some ways supernatural, able to start fires and explosions spontaneously. He is immediately reminiscent of the Devil and Hell; Ed calls him a “warthog from hell.” When Smalls appears on the highway and takes the child, Ed says “what is that?,” and H.I. says “do you see it too?” He might have thought this monster existed only in his imagination. There is surely a hint of an afterlife for human beings, such that punishment for sin is somewhat more certain than a reward for justice. (“Raising Arizona” seems to become “Leaving Arizona,” and waiting patiently for a child and a better life with a family; at least slightly reminiscent of waiting to depart this earth and live in heaven).

MacDonald and Craig seem to reduce Smalls, or the combination of the imaginary monster we first see, and the real Smalls who is eventually killed, to something less than he is in the movie. They seem to think he has existed in Hi’s imagination as his own powerful and vengeful self, getting back at the world.[16] He is also the violent, old-fashioned, excessively violent kind of man who might have been needed to settle the West, but is now a problem that must be solved. We might think even more plausibly that this monster—frightening us with the thought that wrong-doing will be punished—provides a powerful motive for Hi to go straight. Figments of the imagination overlap with things we can only see in movies, and even with the possibility of divine revelation. All of these aspects of what is strange and somewhat frightening might in some cases help to enforce justice, or a sense of the common good, or persuade people to undo the wrongs they have done. By comparison, there is no motive to be good in “Fargo,” or no indication why somewhat ambitious people would choose to be good. There is of course a kind of overblown idea that we should be scared straight by the violence that is unleashed by a criminal who is at least initially non-violent. Is it true that if we allow any crime into the fairyland of the Coen’s Minnesota, through any tiny crack, nightmare violence will result, and this thought should be enough to keep us on the straight and narrow? Somehow this is not persuasive.

Both “Arizona” and “Fargo” present characters with somewhat stunted intellectual lives. In “Arizona” there is more of a sense that such people can have a great deal to teach us. It sometimes seems the Coens are mocking peasant-type people simply because they are peasant-types. The brothers invite audiences to enjoy their own superiority—“thank goodness I’m better/smarter/more sophisticated than that.” In “Arizona,” at least, people whom one would expect to be barely literate come up with erudite and well-formed speeches requiring a substantial vocabulary, and some knowledge of history and literature, including the Bible, as well as popular culture. This is a kind of never-ending in-joke; imagine if people like that were able to talk like that. Perhaps it would provide some solace, including humor, in lives that are otherwise stunted if not miserable. In “Fargo” the good people seem less miserable, but possibly even more stunted.

One solution to the problems of justice is to say we should “go back,” as much as possible, to the healthy city—put the contents of Pandora’s box back in the box, as it were, and close the lid. A more realistic solution, and one that involves more of an exploration of human nature, is to work on specific cures for the “feverish” city, which comes after the healthy city in the Republic. Insofar as utopia has never existed, the healthy city is not a real or historical starting point. We probably live in some variation of the feverish city, where human beings have ambitions both good and bad. Justice comes to sight as “the good of others,” rather than as one’s own good, so an argument must be made that we can achieve both. For Socrates in the Republic, the healthy city becomes the feverish city because of the need for more land, and for soldiers to go somewhere and take land and other goods for the benefit of their own city.[17] From that point, the key to the dialogue is the education of soldiers. It is not possible to simply assume away a rich variety of music (including poetry): we need to draw from a rich palette, or array of possibilities, to find the “right” music for the just city.

“Arizona” presents us with an America that is more like the feverish city. There are extreme desires for recognition and love, as well as cash, but there are possible reforms for this society that are consistent with freedom. Given varied, interesting, romantic characters—some of them like pirates, varying as to the danger they pose to innocent people—there is surely no desire to simply return to the healthy city, where the good people all seek to have limited or even stunted desires. The pirates or criminals, to some extent, stand in for the soldiers in the Republic who need to be educated. The period when such people are needed—the frontier days—are over, so now we need more peaceful people, dedicated to lawful commerce and (of course) the family, including some of those lovable fetuses and babies. MacDonald and Craig are surely correct that the state of Arizona is meant to remind us of the “old” Western frontier. The landscape of the great John Wayne westerns is still visible, even if relatively small parts of it are dominated by huge chain stores, open and brightly lit at night, and “streets” are cluttered up with trailers, poorly-built houses and some of the claptrap of barely solvent retail businesses. As in the Republic, land was taken from someone else, more recently in Arizona than in some places to the north and east. Perhaps the missing characters in both “Arizona” and “Fargo,” both set west of the Mississippi, are the so-called Indians of whom no mention is ever made.

“The Big Lebowski” (1998, action in 1990)

Of all the Coen brothers’ movies, this one may have the biggest ongoing impact. To call it a cult movie is an understatement. Veneration of the Dude as a role model for enjoying life, avoiding stress, and yet handling issues that cannot be avoided by a decent person, has taken on the status of what both Wikipedia and MacDonald and Craig call a “religion”—Dudeism.[18] The character of the Dude, and perhaps this movie as a whole, reminds us that boomers in the West have had a tendency to reject the religions of their parents, and to look askance at religion in general, yet they have often had confidence that some kind of Eastern religion, probably a bit like Buddhism, is entirely a good thing. The Dude is presented as a true hero—prepared to fight for justice, a good friend even when his friends make this difficult, a man who doesn’t look for trouble or try in any forceful way to win converts; both wise and good.

The ongoing joke of the movie is that the Dude is outwardly, and not only outwardly, a pothead slacker who can barely be motivated to do much of anything except go bowling with his friends Walter and Danny. Yet the Dude is also a genuine hero–in some ways the residue of American manhood. He likes things exactly the way he likes them. At least a few times a day he likes a White Russian, which he might jokingly call a Caucasian, just so. He likes the freedom to soak in a tub, smoking a joint—in fact he likes smoking a joint just about anywhere, at any time. His life is summed up by the phrases “the Dude abides,” and “takin’ it easy,” but it is always clear he has a certain stubbornness about having things his way—he will resist being pushed around. (You have to check very carefully, or the store will fraudulently sell you milk that is “off”). His stubbornness, in defense of a sense of property and perhaps propriety, initiates the action of the movie. A wrong has been done to him, and he sets out to correct it. He even makes a little speech about the need to do the right thing, and how it helps to have a pair of testicles in doing so.

The theme of manliness is reinforced by the stranger, who more or less narrates the movie. He is a very cowboy-like character, such as one would find in the old westerns, played by Sam Elliott. Elliott makes it clear he belongs to a bygone era; he’s a bit concerned about what is coming, and he discovers, perhaps to his surprise, that things are not all bad as long as “the Dude abides.” He seems uncomfortable at first with the notion that the Dude is a hero, but he becomes reconciled to the idea that the Dude is the right man for his place and time—the Los Angeles of “today.” Of course, in a very loose way “The Big Lebowski” follows the story arc of “The Big Sleep” (there’s even a Maude), so the Dude more or less does what he has to in order to achieve something comparable to the successes of Philip Marlowe or Lew Archer—drinkers with a sense of justice, who liked their autonomy and their pleasures.

This movie, like the earlier two, has some specific historical and political reference points. Bush Sr. is President, he makes a speech on TV about Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, and the Gulf War of 1990-91 is getting underway. The country will be at war on a bigger scale than at any time since the end of the “Vietnam conflict” (let us say 1973). War is traditionally seen as a test of manhood, and the movie reminds us that an older war may have lingering effects while a new war is prosecuted. The Dude’s friend Walter is a somewhat crazed Vietnam veteran, much more prone to anger than the Dude, always on a short fuse, and willing to fight over little or nothing, usually claiming it is a matter of principle. In his mind, he fights for justice, but we see him commit unthinking and dangerous violence. Perhaps American manhood has been split into at least two: the Dude and Walter. (Danny contributes simple-minded and repetitious dialogue, funny in its own way, and puts up with a lot of verbal abuse from both the Dude and Walter).

In some ways, except for their love of bowling, Walter and the Dude are unlikely friends. (And even when it comes to bowling Walter is inclined to pick fights that the Dude avoids). Back in the Vietnam era, they were to some extent on opposite sides: Walter a soldier in uniform, the Dude a leader of the Students for a Democratic Society, who made their name by protesting the war.[19] In the intervening years, the Pentagon has become clever enough to avoid drafting anyone; one doesn’t have to be too cynical to say one of the main or underlying reasons for anti-war protests was removed. The Gulf War will presumably be accepted by a cross-section of Americans with resignation if not enthusiasm. It is possible to argue that the U.S. was propping up a series of Saddam Hussein-like characters in Vietnam; the Gulf War gave them a chance to oppose and constrain such a leader.

It seems a promising time for Americans of a certain age, coming from different experiences and points of view, to see if they can reconcile their points of view (there may be a synthesis on the horizon) both for their own good and that of their country. What about women, one may ask? There is Maude, a liberated woman and practitioner of New Age rites. She has very little interest in the past, and focuses on certain aspects of the present as pathways to the future.[20] For one very literal example: she has been looking to get pregnant by a promising man with whom she does not plan to have a relationship; in the course of the movie she picks the Dude. He is not only fine with this, it probably instills in him a little optimism about the future. (Yes, another baby, this time barely detectable even by ultrasound). By some miracle, with the 60s some distance behind them, Americans may find some way to unify or even pacify some male archetypes–the hippie, the Vietnam veteran, and the classic cowboy such as one might find in an old movie—and then some liberated women to fill out the picture.

The Dude seems to speak and act for many Americans in believing that the angry Vietnam veteran must be somehow reconciled to his own new life, and to life in ever-changing America. Walter must somehow learn to cool his anger in the short term, reflect on the words and experiences of others, and become less of an angry person in general. Maude is in some ways the opposite of Walter; they are unlikely to speak to each other, or understand each other. The Dude is the wise intermediary. Maude is rightly enjoying her freedom to do exactly as she pleases, but this is only public-spirited insofar as it sets a good example—perhaps especially for women. There is a lot of work to do in trying to help people who are likely to be left behind. In different ways Walter and Donny are charity cases whom the Dude is uniquely well-suited to help.

The three “boys” get involved in a mission to achieve justice—initially simply to get someone to pay for damage that is done to the Dude’s rug, but eventually to rescue a damsel whom they believe is in distress. (Yes, another kidnapping of a wife). There is always some question, when they go from the rug to the rescue of a lady, whether they are thinking more of justice or money; the Dude and Walter take turns believing that the kidnapping is fake before they are both forced to realize that it is. Once again there is a cruel, somewhat successful businessman; in this case it turns out he inherited his money. At any rate, for different reasons the boys are prepared to abandon their usual life and take genuine risks. Of the three, it is Donny who dies of a heart attack, probably related to a violent confrontation between good guys and bad guys. Walter and the Dude both believe something properly formal and ceremonial should be done to commemorate Donny as his ashes are disposed of. Walter turns his speech into an angry shout-out to the forgotten American dead in Vietnam, of whom Donny was certainly not one, and then inadvertently causes the ashes to blow all over the Dude. The Dude, who despite his passivity is always capable of anger for more or less correct reasons, loses his temper. With the very next scene, the movie comes to a close, the Dude and Walter once again bowling together, and some commentary provided by the “stranger.” We hear a repeated refrain: the Dude abides.

Once again MacDonald and Craig compare a movie to some great or well-known texts: in this case, Dante’s Divine Comedy and the works of Emerson. At least in the case of Emerson, there is some support for this connection in the words of the screen play: sometimes, in a crisis, either you eat the bear or the bear eats you. Emerson was referring to a farmer; no one in the movie is a farmer. Emerson says a man who works hard for himself and his immediate family can indirectly benefit all of society; the Dude, remarkably shiftless except in a rare emergency, doesn’t have a family, yet might . . . somehow . . . benefit other people. One might as well add the strange fact, perhaps good for winning a bet, that Emerson coined the expression “do your own thing.”

Is there any real sign of Emerson’s idealism in “Lebowski”? A lot of hard work that is not primarily intended for public benefit, but somehow achieves it? It is hard to find anything like this. It seems to be happenstance that the boys all like bowling. Hobbies might overcome differences, and achieve some of the group identity that used to be achieved in a more sectarian way by churches, for example. Do the bowlers at least raise money for charity, like service clubs? Whatever fire of youthful idealism the Dude once displayed seems to be damped down to coals at best.[21] He has given up on a number of jobs or careers, with a clear sense that they are not good enough; his source of income is a mystery.[22] Does any Emerson material belong in an essay on “The Big Lebowski”? Is any of this enough to make one want to read Emerson or understand his thought?

MacDonald and Craig might have been tempted to compare this movie to Homer’s Odyssey, except that they probably had that work in mind for the discussion of “O Brother” (see below). Two men have survived a great war—the warrior as a participant, the somewhat intellectual type as a critic. Of course in Homer Achilles the famous warrior dies, whereas Odysseus who takes some part in the fighting survives. The Coen brothers’ soldier is wounded psychologically by the war; the dead Achilles actually speaks to Odysseus in Hades and makes it clear he is restless, and regrets the life he lived on earth.[23] Homer’s Odysseus survives a number of adventures after the war, for the most part defending his men until they are all killed. He turns down opportunities for endless sex with gorgeous divine or semi-divine females. The Dude knows better than to seek out adventure, he mostly succeeds in avoiding it, and he enjoys a sexual escapade with Maude. Odysseus goes home to Penelope; the Dude doesn’t have a home in this sense. We can see there is not a particularly good fit, except for the humor that might be pointed out by the contrast between Homer and the Coens; but the fit may be better than what our authors have attempted.[24]

With reference to the Divine Comedy, one is tempted to suggest that this time our authors must be kidding. Dante’s masterpiece is well known for its detailed presentation of Christian theology, particularly what would become known as its Roman Catholic form; there are vivid pictures of many different kinds of afterlife—bad (Inferno) and good (Paradiso), based on one’s actions and thoughts on earth. Dante learns from a pagan poet, Virgil, who presumably has nothing to do with Christianity, and from an idealized woman named Beatrice. Dante is given a chance to immerse himself in both the Christian faith, mediated through the Church in Rome, and the wisdom of the ancient pagans, centered once again in Rome. One might like to think he has found a way to integrate or synthesize the two. Since the Church never put this book on the Index, something they did for Dante’s book on monarchy, one gathers the leaders of the Church believe a synthesis was achieved, with the Roman Catholicism of the high Middle Ages the winner.

On the other hand, when the Church endorsed the Divine Comedy, it was almost always in an expurgated edition, so there may be trouble brewing for the church here. The sins of certain cardinals are highlighted by Dante; and people including “sodomites” who are regarded as great sinners by the Church are not necessarily so regarded by Dante. Dante seems to re-discover patriotism through his contemplation of the ancients, and from this point of view he may find that the Church’s universalism undermines patriotism, and the virtues that are most likely to support patriotism. In short there are at least two possible lists or sets of sins, and two or more possible understandings of what the appropriate outcomes in the afterlife might be. Dante may quietly endorse the pagan approach more than, or even as a substitute for, the Christian one. Either way, an apparent synthesis is not simply something that is brought about by history, more or less delivering the best of the past by a kind of selection; if synthesis occurs at all, it probably involves hard choices, and great thought by great thinkers such as Aristotle, “master of all those who know.”

It would be difficult to find any Coen “text” that corresponds in detail to any of this. Dante presents us not only with a great book, but with an introduction to all the great books in the West up to his time: Roman Catholicism on the one hand, another kind of Roman greatness on the other. It is hard to see how “Lebowski” points us to any book. The idea seems to be that a pothead slacker, perhaps even one who is fairly typical, or barely above average for his kind, reading Sartre (one of whose books seems to be lying around), is enough. There is some aspiration to being good if not great in the movie, but always with the assurance that an easily attainable kind of success in life is enough. There is more acceptance of mediocrity than vigilant or rigorous search for the truth or heroism. Even more than in “Fargo,” it is hard not to think of Nietzsche’s last man; in this case there are even copious amounts of drugs and alcohol to smooth the edges of a life that is designed to avoid “hassle,” and achieve a kind of happiness.

A comparison to the Divine Comedy may be appropriate on one condition: there is no longer any need to integrate or synthesis large or difficult bodies of thought such as “Christianity” and “the greatest works of the Greeks and Romans.” All of that is somehow behind us, yet perhaps still with us in some way—if you believe that history keeps washing up on our shores exactly what we need, or what is best from the past. There is an argument that we don’t need to read a Platonic dialogue. As long as we have graduated from high school (or so) we probably “get it”; we get references to philosopher kings, maybe even Platonic ideas and Platonic love affairs. Our vocabulary and sentence structure come from somewhere, they are in our heads, so we have probably learned from Plato, Jesus, Dante and a bunch of other people, without knowing it.[25] A serious consideration of big, difficult alternatives may have been necessary, or seemed necessary, in the past—in specific times and places. (Perhaps history was always taking care of things, unknown to those poor thinkers hacking away on their books).

Whatever was the case about the past—still paraphrasing an argument—today we can probably say the time and place are right for a kind of completion of human life—there is probably very little left to learn, but somehow we still want to encourage people like Maude to keep on exploring what seems to be new.[26] The immediate, short term reconciliation of Americans over Vietnam, the Gulf War, sex and crime is only a glimpse of the larger reconciliation that is taking place—arguably the reconciliation or synthesis of all thought, from all times and places, with very little help from books.

To the extent that we need to make a case for the present against the past, including a very slight knowledge of books on the one hand, and intense absorption in difficult books on the other, the ultimate test may simply be happiness. Those old-fashioned people, for all their preening about virtue and wisdom, seem to have been mostly unhappy. They certainly inflicted a lot of pain on each other, and on victims who may have been innocent bystanders. It may even be that they inflicted injustice on each other and on innocent people partly because of how mentally unhealthy or screwed up they were themselves.[27] How much better the Dude’s life is by contrast! He hasn’t given up on sticking up for principles, for property, or for people including some he may not like; he has however, come close enough to indifference to such matters that he can truly enjoy a joint and a soak in the tub. The notion of the “last man” involves more than someone who is simply lacking in ambition or drive, putting a kind of simple-minded comfort before everything. The deep thought behind such a life, in what seems a late stage in the West, is the conviction by the “last person” that she or he has reached the pinnacle of civilization—and there is at least vague awareness of evidence to this effect.

At this point we can surely question MacDonald’s and Craig’s suggestion that great movies can substitute for great books—unless we mean by this that great movies can demonstrate our superiority to book people from the past, whereas people in the pre-movie days, by definition, had nothing to say about movies. Can we draw a contrast by saying movies are good at looking at the outside of things, including people, and at best can only consider the inside by indirection or analogy? One thinks, for example, of characters in Ingmar Bergman films, staring off into the Scandinavian gloom. Books, on the other hand, may be quite weak on exteriors, including how people look; they are well known for leaving such things to the imagination. (Of course there are writers in recent times, influenced by the movies, who carve out many “cinematic” exterior details to keep us going). Part of what makes “good” characters in Coen movies seem happy is that they look good, and their lives look good—in their externals.

“O Brother Where Art Thou” (2000, action in the 1930s)

For this movie MacDonald and Craig are on solid ground in making comparisons to Homer’s Odyssey. At the risk of insulting the reader, Homer left behind a pair of works. The Iliad, focused on events of the war at Troy, comes first chronologically, followed by the Odyssey, in which we see Odysseus/Ulysses, having survived the war, make his way home to his wife Penelope through a series of dramatic, indeed fantastic adventures. The great warrior Achilles was killed in the war, but Odysseus gets to speak with him in Hades in the course of the Odyssey. We also find out in this later book how the war ended: not, apparently, by divine intervention, or in any of the ways the gods foretold, but by Odysseus’s ingenuity in thinking of the idea of the “Trojan Horse,” and Greek lies and deception in making the trick work.

One can say that the most straightforward storyline in “O Brother” fits the Odyssey to some extent. The action takes place in the U.S. South in the 1930s, and we are reminded that a great Depression is underway. A man named Ulysses, who goes by Everett, escapes from a chain gang in Mississippi, along with two men who are chained with him. He is the most articulate of the three, the natural leader, and we find out well into the movie that he lied to the other two in order to get them to co-operate. As far as we know at the beginning, the three are treasure-hunters, with only Everett knowing where the treasure is. It turns out Everett has received word that his wife Penny (yes, Odysseus/Ulysses and Penelope), having divorced him at some time in the past, is going to re-marry in a few days. He is determined to get home in order to stop the wedding. He conceals this plan from his comrades at the beginning. Everett gets home, with his companions, just in the nick of time; but there are more complications.

There is a theme of “constant sorrows,” both musical and otherwise. The original three “boys,” all white, have been joined off and on by an African American named Tommy Johnson, who has sold his soul to the Devil in order to become a master of the guitar.[28] The four of them record a song, “I Am a Man of Constant Sorrows,” in order to make some cash; the song becomes a hit in the course of the movie. (“Odysseus” means literally something like “man of constant sorrows”). By performing the song live in a way that wins over the Governor of the state and helps him get re-elected, the “boys” all get both pardons and job offers; this means Everett is “bona fide,” worthy of marriage, in the eyes of Penny who probably never stopped loving him. There is one mix-up about a ring, which Everett seems to resolve with the help of either modern science or divine intervention, or both; in the closing seconds there is another mixup about a ring. Penny can be stubborn, and she has made it clear that unless the ring is done right, she will not marry Everett.

The gubernatorial election in Mississippi intrudes in the movie from time to time, and then becomes a big part of the apparent resolution toward the end. The incumbent, Pappy O’Daniel, seems to be an ordinary crooked politician who has been at it much too long. He, his son, and his advisors, are all grossly fat, with lots of crude observations about the voters, and all at a loss as to how to win. It turns out to be significant that Pappy hosts an “old timey” music show on the radio. The electoral challenger, Homer Stokes (Homer!), seems much more promising, using a broom as a prop along with a “small person,” let us say—to represent the “little guy” that Homer allegedly will always fight for. As far as we can tell, he is against cronyism and corruption, which he rightly attributes to the Pappy administration.

One major twist achieves an intersection of several stories. The three white boys (wearing blackface) come across a huge Ku Klux Klan ceremony in the woods at night. They soon realize that the main event is intended to be the lynching of none other than Tommy. They manage to free Tommy, kill one of their oppressors, and break up the Klan’s party. Remarkably enough, they are wearing blackface since they were hiding in the woods at night. Whether they realize it or not, they have helped to bring about the downfall of Homer Stokes, who is the red-bedecked Grand Wizard.

Both candidates are at the big live performance which ends up saving the day. Stokes recognizes the boys as the “miscreants” of the night in the woods, and expects the crowd to support him in a desire to lock them all up. The crowd is loving the music, wants it to continue, and clearly wants the boys to remain free. Stokes plays the racism card, confident that it can’t miss: he’s sure the boys aren’t 100% white (otherwise why would they have acted as they did?); it was a solemn Klan ceremony that they interrupted (although he doesn’t say the name of the Klan); and the one “colored” boy, according to a good authority, has sold his soul to the devil. None of this impresses the crowd, which cheers as Stokes is carried out of the room on a rail. Pappy, seeing his chance, joins the boys on stage, asks Everett to confirm that they will give up a life of crime, pardons them, and promises them big jobs in his administration. Homer, the former front-runner, is finished; Pappy the cynical incumbent, is a shoe-in. One can pick and choose which part of this story is the most incredible.

MacDonald and Craig see many connections to the Odyssey, but also see that there are great differences between the book and movie. The “boys” in the movie don’t seem ever to have been involved in war in any way; “for the ancient Greeks and Romans, it would be inconceivable to illustrate heroic virtue separated from war” (78). Inconceivable? There is at least an argument that Odysseus achieves a peak of virtue that is different from that of Achilles—more a matter of thinking, less of doing. (Odysseus is a warrior, but he avoids the great one-on-one duels in which one’s odds of survival seem to be about 50/50; he seems to be better at persuading some of the other guys to suit up and get out there). He may even represent a step toward Socratic virtue, in which war seems to play a minor part.[29]

It would be a bit much to expect a first-rate commentary on Homer alongside a kind of philosophic review of the Coen movie—the Coen brothers, always a bit enigmatic in commenting directly on their movies, have denied that they made any kind of careful study of Homer during the making of “O Brother.” It would be tendentious to go on about the role of the gods or the divine in book and/or movie (a bit mysterious in both cases, it turns out), or the difference between aristocratic and democratic heroism. (Everett seems to know from the beginning he can’t succeed on his own, and he learns even more deeply of his dependence on others in the course of the movie). Christianity is very much a part of daily life in the movie, but to say the least it is often hypocritical, and seems to be particularly cruel as it is practiced by the one-eyed bible salesman (kind of a Cyclops as in the Odyssey) and the KKK. The Greeks may have had nothing quite like this.

Everett wavers as to whether he believes his cleverness is enough to succeed—in which case, he can probably do without religion. At the end of the movie, the strangest part of a prediction by an old seer or sage (an elderly blind black man—of course a bit like Tiresias) seems to come true: a cow is found standing on the roof of a cotton house (after a flood). Everett seems more than ever shaken out of his faith in rationalism (68-9, 76, 80). This is at least somewhat reminiscent of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, and the prophecy that Macbeth will never be conquered until a forest called Birnam Wood climbs up Dunsinane Hill; Macbeth takes this as reassurance that he cannot be defeated, but when hostile troops on the move disguise themselves with branches from that very Wood, the prophecy more or less comes true.[30] We have a classic Western text with a hero who has to deal with a domineering wife; but of course the comparison should not be pushed too far. Everett doesn’t kill a king or strive to be king; at most he helps defeat a popular front-runner, and get the marginally superior incumbent elected.

It is worth noting that MacDonald and Craig go to the trouble of indicating that Everett/Ulysses in the movie is not a good candidate to be considered Nietzsche’s last man (78), indicating that they have at least had some doubts on this score. They are probably right about that. Everett is in many ways an ordinary person, clever, sometimes too clever for his own good, but he surely shows a capacity for leadership, and for enduring and overcoming a series of challenges, some of which are unpredictable. He may be something of a modern-day hero. We have already indicated that other Coen characters, in other movies, are better candidates for the last woman or man.

Music, Art, and Justice

Sometimes our authors spend a lot of time on possible connections between the movie and a text, and less time on what seem to be important elements of the movie itself. Perhaps the major part of the movie that is missing from MacDonald and Craig’s account is the music–which is all-pervasive. Bluegrass songs are playing in much of this movie—the soundtrack made more money than the movie itself. Certainly in the 1930s, and even today, this is primarily the music of whites, drawing from deep wells of inspiration in the South. There is an authenticity to this—the characters with speaking roles are almost all white. In the dramatic triple reversal—the boys getting jobs with pardons, the governor gaining the upper hand in the election, and Everett winning back his wife—it is the music that seems to have this power to change people, and bring about transformative events. There is an undeniable sweetness and power to the bluegrass that we hear; an appeal to common humanity, and often to God. Several songs are about seeing the best in things: looking on “the sunny side of life,” and celebrating a beloved (“You Are My Sunshine,” a song co-written by an actual Governor of Louisiana). Even if one has suffered a great deal in life, one can dream of “The Big Rock Candy Mountain” (the song that plays over the opening credits). The most central and repeated song, “I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow,” presents a sufferer whose ordeals somewhat resemble Everett’s. He looks forward to “sleeping” in his grave, and then to meeting his beloved “on God’s golden shore.”

It is difficult not to wonder if the Coens think music, or a special kind of music, or social events and attitudes that develop around the music, might have caused dramatic improvements in the lives of people. Or is such a thing only likely in the movies as opposed to real life? The boomers are used to thinking that “their” music has made the world better and more just; such music has something to do with making the Dude the Dude in “The Big Lebowski.” Since this is all taking place in Mississippi in the 1930s, one has to ask further: if it is at all likely that music can made people more attached to each other, more inclined to seek justice, how would this apply to relations between whites and blacks in the Jim Crow regime of segregation?

MacDonald and Craig remind us that the real U.S. South of the 1930s would have displayed far more violent racism than we see in this movie. When Pappy promises jobs to all the “boys,” it seems clear that he includes Tommy, and it may be that “the crowd requires” this move on his part. In the movie, “the crowd has come to see what Pete, Everett, and Delmar already knew: segregation is an artificial and hateful construct” (76). A strict reading of the “triple reversal” scene might indicate that the only reason the white audience rejects the Klan is in order to hear more of the music; neither they nor the Governor who is now likely to be re-elected has any intention of shutting the Klan down, or ending segregation. Nevertheless, we might hope. The movie “ennobles the Jim Crow south, especially the south of the poor whites.”[31]

There are brief references to the Jim Crow laws of the day. At one point when the police catch up to them, the three whites soon find that Tommy has already “lit out . . . scared out of his wits.” Whatever goes badly for hopeless lawbreaking whites is likely to go even worse for a black man, whether he has broken any law or not. Everett foolishly tells the blind radio station/recording studio operator that three of the four “boys” are Negroes, possibly thinking that “black” music is better than “white” music. The producer actually refuses to record “Negro music,” claiming there is no market for it; so it may be that Tommy’s only chance of making money is to play with white performers. (Tommy does get to perform a nice blues number at one point—just for the boys). Otherwise, though, our white heroes are so badly off—so unable or unwilling to plan for the future, so naïve about the people they are up against, so familiar with poverty and even starvation—that they never seem all that much better off than many of the blacks they see around them. The chain gangs are not segregated by race—even if the blacks outnumber the whites there. The three grave-diggers near the end are all black, and they sing a beautiful spiritual—the first one we hear in the movie. This may be a job that whites cannot make their fellow whites do, except in a real emergency.

There is a constant threat of lawlessness, affecting both whites and blacks. Tommy is nearly lynched on his own; but Pete is also nearly lynched by a sheriff’s gang, and all four of them come close to being lynched in the last minutes of the movie. The three white boys are reported to the authorities by Pete’s close relative who is hoping to collect the bounty; later the Sirens, who at first seem barely human, turn Pete in for the same reason. It is apparently not worth anyone’s time to turn Tommy over to the authorities. The sheriff who has been pursuing them—who is much more interested in runaway convicts than a free black—is not impressed by the law, which he says is a “human institution”—presumably meaning purely conventional, not natural nor ordained by God. Surely this is the spirit of the Jim Crow regime: the people in charge will make chosen victims suffer, usually on the basis of race combined with poverty; they will use the law as a cover or pretense; but they will change the law as necessary in order to do as they like.

Now the incredible part: for at least a sizeable group of people in Mississippi in the 1930s, one hit song, culminating in one live performance, holds out the hope of changing all this. The people no longer have any allegiance to the Klan or a racist, lawless regime; they want to recognize not just the equality of human beings, but the right of talented musicians of any race to be recognized, so that everyone can enjoy their music. It is not even a case of white people being won over by black music, such as spirituals or Delta blues—a phenomenon that came about in the 50s and 60s.[32] Rather, it seems that white people can be inspired by the beauty and truth of their own music to transform their political and social world, making it more just and loving. “Constant sorrow”–in a place where more or less everyone is poor, and trying to make the best of it, and where living in prison isn’t all that much worse than freedom with starvation–knows no racial distinctions.

One might say this exaggerates the power of show business to do good, or make the world more just. One might say it amounts to a strange summary of events in the Jim Crow south in the 30s: thank God the white people were there with their music to save the day. Why the focus on white people and their music rather than black people and their music? To show black people singing and enjoying momentary pleasures, as the white people mostly do in the movie, would be to imply that blacks were basically satisfied to live under Jim Crow—their thinking was so co-opted or controlled by whites, they couldn’t imagine anything better. Music alone, it might be suggested, provided solace for, and somehow even compensated for, a lot of suffering. This would have been much more of a defense of Jim Crow than the Coens provide—something in the spirit of Disney’s “Song of the South” (1946), which Walt Disney apparently believed was going to be his great classic.[33]

If there was a kind of alternative future available for the South, in which music brought whites and blacks together, why did such a change not happen? If the potential was there, why did the South remain stuck until it was forced to change, to some extent by “outside agitators,” and the U.S. federal government, in the 1950s and 1960s? The boomers have often suggested that they contributed to ending injustice in the South simply by supporting—and paying for—various kinds of roots music, and then the “rock ‘n roll” that combined some of them. Do the Coen brothers actually think music is better—more likely to improve the world—than their own art form, the movies?

The three white boys see a movie together in a theater—Pete, unfortunately, for the time being once again in a chain gang. We see an attractive young woman taking off some of her clothes, and then performing a kind of dance for a few men—presumably some kind of audition. The movie is “Laughter in the Air” (1933), about a group of theater people trying to put a show together while the new female lead is pursued by both her male co-star and a lecherous producer who has put up the needed money. The actual stage show might show a woman in a somewhat skimpy outfit, dancing, but there would be no reason to show her undressing for an audition, with ominous overtones for her, or for vulnerable women in general. In the movie the lightheartedness of the show, perhaps what seems the innocence of a woman undressing in a “business” context, conceals, but is linked to, the grossness of some of the human beings behind it. Obviously something similar could be true of a musical show, but there may be something more objective in whether music is good or not, or pleases an audience or doesn’t. Movies, by showing or promising female nudity, have raised moral debates from the pre-Code days until today’s MeToo movement.

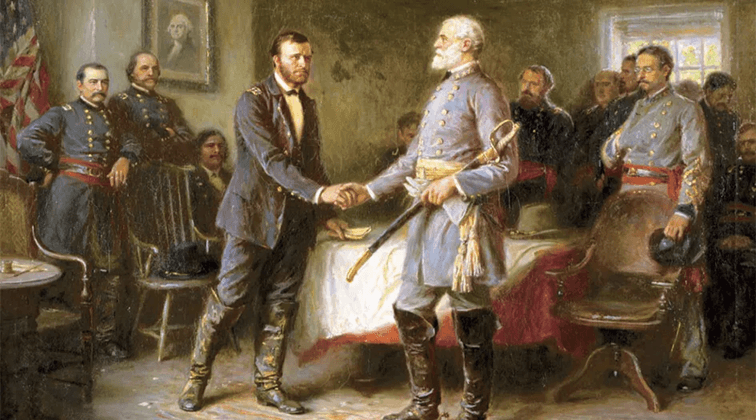

Given the moral issues that are raised in this movie, why do the Coens not attempt to comment on previous movie depictions of the South? As soon as one asks the question, one thinks not only of “Song of the South,” which came out a decade after the events of the movie, but of “Birth of a Nation” (1915), a silent movie which was hugely popular, including in the South. According to Wikipedia, this film still stands as one of the landmarks of film history—the first American motion picture to be screened in the White House (for Woodrow Wilson, whose support for “the self-determination of peoples” may have had some exceptions or limitations); its release one of the events that inspired the reformation of the Ku Klux Klan. The movie may have been responsible for the clarification and popularization, for many people, of the view of the white South as “the lost cause,” that fought the Civil War in a more noble way than the North did, and was forced to subjugate people who were not qualified or able to achieve freedom. “Gone With the Wind” (1939), released after the events of the Coen movie, probably took the mythic and sympathetic view of the South even further. Clearly there was a receptive audience for all this—a justification for the white South inflicting deliberate, often lawless cruelty on many people, and for the North doing little or nothing about such events after the time of Reconstruction.

There have been so few movies based on events in the Civil War that are pro Union, it has been said that the Union is “Hollywood’s lost cause.”[34] Possibly Buster Keaton’s greatest film is “The General” (1926); he plays a railroad engineer who is desperate to join the Confederate army but is declared unfit for active service. He manages to perform heroic service for the South despite setbacks, using his skills as an engineer along with his usual ingenuity and physical agility. He apparently explained his decision to make his movie pro-Confederacy by saying “It’s awful hard to make heroes out of the Yankees.” In “Our Hospitality” (1923), another masterpiece set in the 1830s (decades before the Civil War), Keaton plays a southern lad named Willie who is raised in New York in order to keep him out of a Hatfield and McCoy type family feud. On the train ride south to claim his inheritance, he falls for a girl who is from the “other” family; her brothers keep trying to kill Willie. It is against the rules of Southern hospitality to kill him when he is inside the “other” family’s home; tremendous efforts are made to kill him somewhere else. Generally speaking, Southern males in this movie have a kind of crazy obsession with violence. One might think the constant presence of slaves might help to explain this attitude, but Keaton doesn’t really go in that direction. Willie’s old family estate is a pathetic shack (like the place where Everett grew up); perhaps if the South could give up the feuding and violence, they could make some economic and material progress.