Saving Superman: A Daunting Lesson from Old Christianity

“The private life is dead”—thus spoke Strelnikov, Pasternak’s infamous prophet of a new “manhood,” in Doctor Zhivago. The private life is supposed to entail a selfishness to be immolated on the altar of a socialist ideal, a dream to be realized beyond all poetic openness to divine transcendence. Indeed, absolute closure to divine transcendence is the conditio sine qua non for the realization of Strelnikov’s dream: only by killing poetry as denounced by socialists—a poetry open to God—can the new man emerge, “beyond good and evil”. Dr. Yuri Zhivago’s poetry, in particular, is too ambiguous, too dangerous for socialists, including Major-General Evgraf Zhivago, the doctor’s half-brother. Evgraf is secretly attracted to Yuri’s poetry, to the horizon it opens up before its reader, but he represses his attraction, lest it expose a dimension of Evgraf’s being that resists assimilation to socialism’s dream of a new, neo-Machiavellian manhood.

Pasternak’s villains are all but alien to the conflict underpinning the universe of comics’ idealistic super-heroes, foremost among them, the world-renowned Superman. The conflict in question is not the one between justice and injustice, or between good and evil (at least not as these are typically represented in comics and films), but between an ideal and privacy, continuously struggling against each other, neither being powerful enough to overcome its opponent. The ideal, usually conceived as “justice,” is a universal dream to be realized, whereas privacy remains a function of sentiments, fear-bound sentiments. No more can the lofty ideal overcome all sentiment, than the latter can dispense with the former. The private and the public are continuously—and creatively—at odds with each other, never allowing each other to escape their battlefield onto higher grounds. The resolution of the conflict is systematically out of reach, given the manner in which private and public interest are conceived, or framed. Had public interest been sought in terms of a natural, or an original common good, private interest would not have been condemned to frustration; the public would have been sought as the perfection, not abolition or destruction of the private; not, then, as an ideal rising above the ashes of privacy, but as a “Paradise Lost,” a now hidden origin presupposed by our present condition, or by the world in which we find ourselves lost.

Our modern superhero knows nothing of a Paradise Lost, which is now obscured nostalgically by the dream of Krypton, a planet long destroyed. Since there is no sense to returning, progress is hardly a choice, but practically a destiny. There is no trace of regret in Superman’s embracing of his future-oriented destiny, especially insofar as what is lost was not nearly as good as what the future might be. And yet, the future demands a “socialist” sacrifice that the superhero is not willing to make, if only because he fears that in abandoning his privacy (represented by his private identity as Clark Kent), he would no longer be able to fight for his universal cause.

There is something dreadful, even diabolical, about an ideal uprooted from any and all privacy, as a universal pretending to be cut off from particularity; something far too abstract to demand that we keep fighting for it. Whence the suspicion that the ideal stands or falls over the survival of private life, which might very well be the ideal’s own justification; hence the question begging to be asked: does Superman fight ultimately to defend privacy? In other words, is the ideal a (Machiavellian) mask of private interest, a mask that private interest is in dire need of? If so, then the two—privacy and its mask—would be ineluctably intertwined. Hence Superman’s double-life and his seemingly ineluctable frustration.

Superman is, as it were, condemned to being torn between two lives. On the one hand, pursuing private life alone would be suicidal; on the other hand, the ideal of public interest cannot perfect private life any more than a mask can replace its living support. As long as the public (ideal) and the private remain in tension, Superman will live on and, with him, frustration. Yet, frustration drives Superman to choose between one pole and another of his life; the superhero is continuously tempted to settle matters, either as Pasternak’s uncompromising socialist, or as a “normal” bourgeois entirely assimilated to the status quo by having renounced to questioning it.

Not any kryptonite, but frustration and the perplexity underlying it, constitutes Superman’s ultimate weakness, that which exposes him continuously to the loss of all dignity. Superman’s weakness is, of course, not his alone, but that of modern man and thus, too, of his democracies. It is that same weakness that invites us to reconsider a public interest perfecting, rather than destroying privacy; much as the “grace” that, in St. Paul’s footsteps, Thomas Aquinas defends as “not abolishing, but perfecting nature”. The discovery or rediscovery of such a public interest would confirm the thesis that the perplexed life is neither our only, nor our best alternative to moral or political suicide.

How are we to understand Aquinas’s appeal to a perfection of natural inclinations, beyond any socialist ideal? Aquinas’s “grace” perfects nature in the respect that nature possesses and presupposes its own divine perfection: grace is not a public ideal imposed upon our private life, ex machina. Thus does St. Thomas write: “since grace does not abolish, but perfect nature, it is becoming for natural reason to serve faith; just as the natural inclination of the will follows from love” (cum gratia non tollat naturam, sed perficiat, oportet quod naturalis ratio subserviat fidei; sicut et naturalis inclinatio voluntatis obsequitur caritati).[1] Being divine gifts, Aquinas’s faith and love (fides et caritas) exemplify grace, so that “since” (cum) grace does not replace nature, neither does faith replace natural reason, nor does love replace our natural desire (naturalis inclinatio voluntatis).[2] Neither does our loftiest end impose itself upon our will, nor does it demand that we abandon our will. On the contrary, our loftiest end is none other than the perfection presupposed by our natural desire; our natural desire’s own source. The divine foundation of our nature does not dispel, but sustain our imperfect nature. In this respect, Aquinas invokes faith as guide of our natural reason, a reason that is after an end that it presupposes, even as it fails to fully comprehend it.

A certain modern prejudice might lead us to misconstrue Aquinas’s fides as repressing reason. What alternative reading makes sense? One that understands fides as the “divine confidence” thanks to which natural reason can proceed—not confidence in reason as “natural,” to be sure, but confidence in reason’s own presupposed divine(d) end, or “original” perfection (telos). Aquinas’s divine faith or confidence makes sense only insofar as it points directly to divine perfection as the foundation of reason itself. Fides is a gift stemming from the very ground of reason. Divine perfection must be compatible with natural reason’s own free exercise and thereby even with confidence in natural reason as such: confidence in the divine end of reason does not deflate, but sustain both natural reason and our confidence in it—our confidence in our own powers of understanding. Far from driving us to dispense with the proper, human end of natural reason, the divine gift of fides confirms that end natural to man, or the role most proper to reason in this world. In sum, the divine end does not replace, but disclose our human end, as a poetic creation of natural reason, a creation serving as indispensable mirror of divinity.

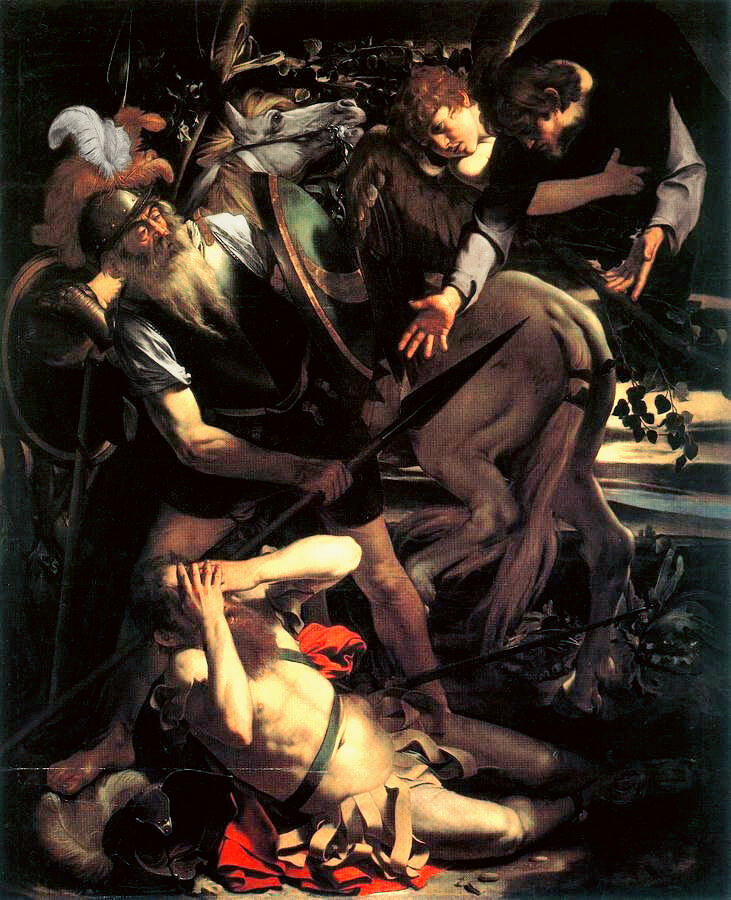

Natural reason alone, natural reason devoid of the divine gift of confidence is most likely to lose itself in its own constructs, not being spurred to rise further, especially backwards to question itself, to understand itself as meaning what it presupposes. Natural reason requires confidence especially when it comes to turning back to natural reason’s own ground. There, confidence is outright courage. What is it that encourages natural reason to transcend its natural limitations, if only by seeing its objects, no longer as future-oriented answers, but as origins-oriented questions? Aquinas’s Christian answer is, “miracles”: only extraordinary, miraculous signs can draw natural reason to free itself from remaining trapped in its own musings; for, only marvels can awaken the confidence that can save us from taking our present condition for granted.[3]

Unaided natural reason is an “outward” quest in the fundamentally unquestioned medium of the senses: our natural reason orders the senses, without questioning their ground, even as it may divine it. Where, in the face of the extraordinary, natural reason turns back upon itself reflectively, or as a question (thus, where natural reason becomes a question for itself), it comes to face the illusory character of the sensory world; what had appeared to be self-evident or “natural,” now appears constructed, even feigned: the sensory emerges even as a poetic fiction, so that “genetic” explanations no longer speak for themselves.[4] Natural reason seeks its cradle elsewhere.[5]

Yet, mere awareness of the illusory character of the sensory does not suffice natural reason to dispense with the sensory, which we will still need as an “enigmatic mirror” of truth; whence the Scholastic insistence that the human mind does not understand anything to which it was not moved by the senses (nihil est in intellectu, quin prius fuerit in sensu). Our natural, original, or proper capacity to choose (“reason,” as defended by Milton),[6] or shall we say, the marrow of our own humanity, tends towards an end that it necessarily sees “in part” (ἐκ μέρους), or as an “other” mirrored enigmatically (ἐσόπτρου ἐν αἰνίγματι), as St. Paul would prophesize, even as that end is, in itself, none other than the seer; not, to be sure, the seer that sees only alterity, but a prior or presupposed seer who sees alterity as itself.[7] Such is the end that faith presents us as the mystery of our desire, namely divine love, the caritas or “care” that Aquinas invokes as consummation of our thirst.

Faith, however, does not displace, let alone replace natural reason; rather than rendering our senses expendable, it sustains natural reason as a capacity to order the sensory in properly human terms, or so that the sensory bespeak the divine. Even the “revelation” of caritas via fides does not call our natural reason away from the senses; on the contrary, it helps natural reason gather the sensory teleologically, in the interests of the disclosure of a political universe, a pious world of civil consciousness, or of a poetic imitation of divine caritas. In short, divine faith is the confidence that raises natural reason to meet the challenge of reading the natural universe as a moral mirror of divinity. The miraculous is thereupon understood, not as opposing the “natural,” but as confirming nature’s divine ground—as a sign of what nature really is, or of what nature is “face to face” (St. Paul’s πρόσωπον πρὸς πρόσωπον). Natural reason alienated from the divine confidence it must ultimately presuppose, will not recognize the miraculous, or nature as divinely grounded. In this respect, Lessing is right in suggesting that faith and the miraculous are intertwined to the point that natural reason accepts miracles only through faith.[8]

No sooner do we understand faith as a divine gift presupposed by natural reason than we are no longer fettered by the perplexity characterizing modernity. Instead, we are well placed to rise above all perplexity and thus, too, above Superman’s frustration, back to an ancient appreciation of the mutual compatibility of man’s two ends, the political and the theological, or, to speak with Dante, Monarchia (Imperium) and Ecclesia.[9] Beyond readings of Dante as Latin Averroist,[10] we can appreciate Dante’s appeal to religion in the light of the foregoing reading of Aquinas, whereby our divine end is a divinely given “gift” (gratia) disclosing our freedom to pursue our human end, namely moral-political order as poetic imitation of divine order—a mirror, to return to St. Paul, in which we can know, if only in enigmatic terms, truth itself.

Old Christianity shows us that Superman can be saved—and with him, our modern republics—insofar as our ideals are never ends in themselves: the public good (Cicero’s utilitas communis) is not an “ideal” to be socially engineered by leaving religious ends behind, but the poetic mirror of a divine order. What would it take for Superman’s world to reacquire appreciation for that mirror, thereby transcending our peculiarly modern limitations? What would it take for us to regain the confidence needed to support natural reason in the systematic pursuit of its proper end? The first Canto of Dante’s Inferno suggests a formidable answer: what we need is a marvel more daunting, indeed more earth-shattering than anything—macroscopic or otherwise—that our social engineers could ever fathom.

Notes

[1] Summa Theologiae, I, Q. 1, art. 8, ad 2.

[2] For a further exploration of Aquinas’s argument, see my upcoming “Dante and Christianity,” in Mediaevalia: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Medieval Studies Worldwide, Vol. 42 (2021).

[3] For a parallel discussion, see the Buddhist Discourse of the Awakening of Divine Faith (大乘起信論Dasheng Qixin Lun), Taisho Tripitaka Vol. T32, No. 1666. The title term dasheng, ordinarily translating the Sanskrit “Mahāyanā,” is rendered here as “divine,” to distinguish its faith from “self-confidence,” or 自信zishin. The 大da of大乘dasheng is arguably best understood in the light of the classical Chinese 大學daxue, entailing a shift from our ordering of things to an order presupposed by our ordering, namely 物格wu ge. See also 邵雍Shao Yong, The Contemplation of Things (觀物Guanwu), Ch. LXII.

[4] Modernity’s “evolutionism” would make no sense to Aquinas, for whom the sensory world is not ordered mechanistically, according to quantifiable “natural laws,” but poetically, both by man and by a divine mind.

[5] Compare Kant’s “transcendental” turn spurred by Hume’s skepticism. Kant does not turn to the divine awakened unreflectively by a marvel, but to “formal” (read, empty) conceptual structures, “awakened” by criticism and thus in the medium of reflection. On the nexus between the miraculous and fear, see my “Autobiography as History of Ideas: An Intimate Reading of Vico’s Vita,” Historia Philosophica: An International Journal, Vol. 11 (2013): 59-94. Vico returns to divine fear as means for our awakening to the metaphysical foundations of our experience. For Vico, modern “Cartesian” philosophers are not radical enough.

[6] See Milton, Paradise Lost, 3.108, echoing the central thesis of Aeropagitica.

[7] 1 Corinthians 13:12.

[8] Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, “On the proof of the spirit and of power,” in Lessing: Philosophical and theological writings. Translated and edited by H. B. Nisbet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

[9] Dante Alighieri, Monarchia, esp. Book 3.

[10] A recent example is found in Christopher Lewis Lauriello, “Church and State in Dante Alighieri’s ‘Monarchia’”, Boston College, 2015. http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104155.