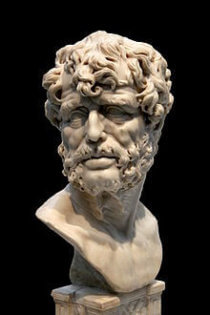

Seneca

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (c. 4 B.C.-65 A.D.) was a late, Roman Stoic who contributed to the concept of a cosmopolitan community governed by a global ethics. As a Stoic, Seneca conceived of the world as a single living, rational animal. This world animal had earth at its center and was identified with the Roman god Jupiter whose mind was perfectly and completely rational. Apart from the gods, the only other rational animals were humans. The power of reason not only was a bond between humans and the gods, but it also provided a sense of solidarity and common purpose for all of humanity. This was at the core of Seneca’s Stoic philosophy and the basis for his understanding of natural law. For Seneca, the natural law made humans capable of reason and thereby able to form a universal community that transcended geographic place, social position, or national citizenship. Even slaves were able to partake in this universal, philosophical community, as Seneca wrote in On Benefits, for the slave was bounded to his master only in body but not in mind. This universal or cosmopolitan community was available to every human who was willing to actualize his or her potential of rationality.

Seneca continued this theme of the cosmopolitan community in two other essays: On the Private Life and On Peace of Mind. Addressing the question whether the philosophical or political life was superior, Seneca wrote the need for both kinds of lives in order to flourish fully as a human being. Both philosophy and politics represented two aspects of a single world to which humans simultaneously belong: the world of politics was the particular and local realm in which humans lived; the world of philosophy was the universal and cosmopolitan world of which humans were members. Philosophy enabled humans to partake in the universal community of reason, restored a peace of mind in the contemplation about such truths as virtue was the only good, and provided humans a code of ethics to guide their actions. Politics was the practice of performing good deeds to people in a particular community as one’s ethical duty required. Although Jupiter may control the course of nature, this did not mean that humans should confront life passively; rather, as endowed with reason, humans should use it to take control over their lives as much as possible. Thus, the choice between the philosophical or political life was a false one for Seneca: both were needed to be a human being in one’s community and in the world.

However, it is important to note that the actual outcome of one’s action was inconsequential to Seneca. After recognizing the norms that nature had laid out for them from their reason, humans should strive to realize these values in social and political action. But if they were unable to achieve those objectives, failure was not the outcome, for the gods did not intend it (of course, if one were successful, then life would have better than before). Seneca’s beliefs included a deeply embedded recognition that once someone has done his or her fullest and best, the outcome always would be positive for that person irrespective of the result because what counted the most was the development of one’s capacity of reason. Whether the actual outcome was successful was immaterial as long as one’s reason continued to be cultivated. The criterion for good or bad therefore ultimately rested upon the development and use of one’s rational capacities.

Seneca’s cosmopolitanism consequently was fundamentally apolitical in spite of his requirement for political action since outcomes are inconsequential. Not surprisingly Seneca has no conclusions for the authority and forms of government, institutional reform, or divisions of powers because what matters more was the moral character of rulers and citizens. The development of one’s rational capacities provided a path of liberation and entry into a cosmopolitan community in a way that politics could not. Whereas the political life was dependent upon circumstances for success, the philosophical life was not and therefore allowed humans fully to control this aspect of their existence. The political life was necessary for human flourishing, but Seneca recognized that humans could not control this aspect of their life completely, unlike the philosophical life. The result was that Seneca’s writings have the character not only of a moralist but of an inward-looking moralist.

According to Seneca, the ideal person did not have emotions because emotions were irrational and therefore harmful to the development of one’s rational capacities. Instead of emotions, one had rational affective reactions and dispositions. The passions, such as anger, were the greatest threat to the development of one’s rational capacities. In On Anger Seneca rebutted the position that anger was necessary for both political and military life as an appropriate public response to evil. For Seneca, humans were born for mutual aid, while anger aimed for destruction. Furthermore, one can be motivated to action by duty and virtue alone: anger was not necessary to prompt a public response to evil. In fact, when one stepped outside the boundaries of reason and lost control, one was prone to excessive violence and cruelty as sparked by anger. Anger therefore was not only unnatural but it was not necessary.

Because the ideal person was motivated by duty and virtue as dictated by reason, he or she can perform positive social and political actions like mercy, as Seneca urged rulers like Nero to do in On Mercy. The practice of mercy not only honored the ruler but ensured the safety of the state by promoting friendship even among enemies. One should punish people for either consolation of the injured party, improvement of the guilty party, or for future security; however, since the ruler has no equal, he cannot strengthen his position by punishing others and therefore should consider mercy as a viable option. Some other social and political actions Seneca advocated were benefiting others (On Benefits) and to be useful in public life as much as possible after one retires (On the Private Life). Although Seneca was concern for others and the well-being of the state, he ultimately believed that these goals were internal to a person’s character and, as a result, one should spend the most time on cultivating one’s rational capacities.

Seneca’s contribution to global justice was his understanding of a cosmopolitan community based on the development of a person’s rational capacities. The recognition that regardless of social position or national citizenship, all humans have this potential to develop their reason and therefore deserve dignity and respect made Seneca a forerunner in the development of human rights. Although Seneca had a universal code of ethics as informed by natural law, he was not a forceful advocate for its implementation because his conception of cosmopolitanism was fundamentally apolitical. Thus, he has little to offer in addressing questions of distributive equality or institutional reform. Nonetheless, Seneca provided the path toward answering these questions in his Stoic philosophy that called for the fellowship and solidarity of all rational beings.

Further Readings

Bartsch, S (2009) Seneca and the Self. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Cooper, J (2004) Moral Theory and Moral Improvement: Seneca. In: Cooper J (ed) Knowledge, Nature, and the Good: Essays on Ancient Philosophy. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp. 309-334

Griffin, M (1992) Seneca: A Philosopher in Politics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Inwood, B (2005) Reading Seneca: Stoic philosophy at Rome. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Nussbaum M (1994) The Therapy of Desire Theory and Practice in Hellenistic Ethics. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Seneca (1913-2004) Works: Loeb Editions. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA

Strange, S (2004) Stoicism: traditions and transformations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

This essay was originally published with the same title in Deen Chatterjee, ed., Encyclopedia of Global Justice (Springer Publishing, 2011), 993-94.