Symbols in Painting

“The second fabling-talk [parlare], which corresponds to the Age of Heroes, the Egyptians indicated to have been fabled [parlato] through symbols; to which are to be retraced Heroic Achievements; and those must have been the mute likenesses, which by Homer are called the signs, with which Heroes wrote; and consequently they must have been metaphors, or images, or likenesses, or comparisons; which then, with articulate tongue, make up the whole apparatus of Poetic Speech.” (SN44, Bk. 2, « Corollaries about the origins of languages… »)[1]

Who better than Hyeronimus Bosch has let symbols speak in painting? But what are “symbols”? Giambattista Vico exposed the “heroic” sense of the term. With respect to its etymology, the symbol (symbolon) is a “convention,” or “alliance” standing between the vulgar and the sacred, as an enigmatic mirror of what is hidden. In or through it, the vulgar or earthly is somehow gathered or cast back into the divine. The painter himself produces the symbol as poetic medium allowing the painter to gather all that is Low (the sensory) so that it may reflect what is High (the noumenal).

If, for the painter, the symbol is none other than the painting itself, how are we to understand its conditions of possibility? In response to what does the painter draw “material” into a painting? The classical “Platonic” answer suggests that all painting presupposes a turning toward eternal Ideas, forms that the painter somehow responds to. Do Ideas guide painters, if only unbeknownst to them, into forging their symbols—their paintings? Does Platonic philosophy expose painting as a divine calling?

How does the painter paint, or “manage symbols,” in an original sense? Platonism suggests that he does so by “heroically” (Vico) gathering our moral-political universe to “signify” the otherworldly. The heroic painter would not take his bearings from a pre-moral/political material, to thereupon “express himself” or “his feelings” in public; he would not publicize the private. Instead he would convert, or restore the public from the corrupt plane of vulgarity (“the physical”) onto the integral plane of sacredness (the noetic)—and this act of “transposition” of a mortal city of vice into an immortal city of virtue would be performed speculatively: the painter would turn physically decaying humanity, or our mortality, into a poetic mirror of divinity, a symbol looking back to a lost origin or Paradise. If Platonism corresponds to man’s proper or original telos, then the painter redeems his world, if only by pointing back to its lost goodness.

Modernity teaches otherwise, insofar as it relegates the symbol to the role of translating the particular into the universal—the merely-physical into an ideal conceptual abstraction and so into a human construct, as opposed to a natural or original ground. In the context of modernity, the painter is compelled to serve a socialist dream, or the realization of the universal society dreamed of by modern man—a society grounded in mercantile principles replacing classical divine law. The mercantile or “material” is supposed to be presupposed by the simply legal.

The classical alternative that modernity obscures entails the poetic quest to reflect the divine as transcendent dimension of the physical. With modernity, the physical is merely that, as a mere “raw fact” (factum brutum), a datum begging to be smothered ex machina, from without. Nature is a physical or sensory indetermination we are compelled to conceal by applying a mask over it, by erasing its face, defacing what is supposed to harbor the greatest threat to “the machine,” to the ideal standing over nature. Instead of waiting gently for nature to reveal her secrets, we impose our voice upon her. In a word, we repress nature.

The repression of nature frustrates the machine, which soon falls back upon itself in search of a voice—of answers. Indeed, the machine must give or sacrifice itself for a return, investing its own resources to acquire new fuel. Now, insofar as “the machine” represses nature’s “voice,” the machine is starving itself, merely extinguishing its own powers.

The problem at hand is illuminated by the Biblical account of Eden. There, Adam receives the forbidden fruit from, or rather through Eve. Through Eve’s senses, indetermination enters into Adam’s naming reason, his reasoning about types. Now, what happens when the indeterminate enters into the determinate? Thereupon, the latter can no longer remain the pure Garden of good or divine determinations. The good has been exposed, if not to evil, then to the possibility thereof. Adam now knows that he can die, or lose determination. He has forsaken the purity of determination already in the act of seeking it outside of the Garden of divine determinations. He has “brought in” indetermination the wrong way, or from the serpent and thus through a devious, sophistic, deceiving discourse, as opposed to the upright, illuminating discourse of an unnamed God. Instead of letting the divine speak to him through sensory nature within reason’s own bosom, Adam lets the serpent, the absence or betrayal of the divine, speak through Eve—Eve, the senses that have been “extracted” out of the full reaches of Adam’s reason.

The result of Adam’s gesture is horrible, even if God steps in to redeem it by blessing Adam’s art of camouflaging his nakedness, or mortality. Through art, Adam can perfect his poetic education, his education to a language allowing Adam to receive the indeterminate without being forced to abandon the determinate and so without falling into indetermination. For such a falling would be evil, the loss of good par excellence.

As Adam exercises his art(s), as he shapes his world, he comes to recognize that he does so through God’s own speech, or that human production is achieved providentially. Our art can help us perfect our language insofar as a “prior” language—whether God’s own or the serpent’s—is at work within art from art’s very inception. Art is then necessarily ordained, or justified by a transcendent (or “trans-descendent”) agency, even as this agency acts within art’s own work, as its latent mover (energy).

Even where art is moved by the serpent, it does not lose its original inclination towards the good; it merely mistakes, if only for the flash of a moment, divine indetermination for the good simpliciter. Adam’s fault (his “forgetting” evil) is understandable, even though it is not necessary. Mistakes do happen, even if there was more to Adam’s fault than an impersonal happening. Adam sought respite from his work and in resting he was drawn to transcend his ignorance availing himself of the first means “ready at hand”. Had the serpent not approached Eve, Adam would have sought “the beyond” through God’s own counsels. Yet, the serpent was there to insinuate its devious speech through Eve’s senses and into Adam, to mislead his reason; and so, Adam committed his culpa, his “fault”: he caught a fleeting glimpse of totality, retaining little more than a bitter sense of death.

The biblical account of Eden has taught us that there can be no art without God, that art is ultimately or originally good, and perhaps most urgently that Adam, the anthropos, is not meant to abandon the quest for metaphysical heights or depths in favor of a mechanistic appropriation of nature as mere-surface. Adam’s natural or hidden desire for “being like God” is not to be fulfilled on the plane of human existence, for its only justification derives from our capacity for artful, heroic participation in divine indetermination, where art is divinely inspired to reflect the divine in man, and ultimately, as St. Paul’s Letters to Corinthians signal with unsurpassed vigor, where man is art, the mirror (or “mask”) itself–man as divinely inspired reflection of the divine.

What is objectionable about the snake’s craft or art pertains to the problem of place. The snake induces Adam to lose his proper place, as it were. Both Adam’s forbidden fig and his own intention are good. Yet, by eating via the snake Adam projects himself outside of the Garden, somehow placing himself in a situation of danger, or instability, where he is naturally prone to fear, sensing himself as naked—mortal. By acting via the snake’s discourse, man reminds himself of his mortality, scaring himself back into the Garden in search of a refuge (as Vico never tires of reminding us). Here the Garden appears to us as a hiding place, a way to escape from death, rather than as an unqualified blessing. We do not love it simply for its own sake, or as a good in itself. We love it because it helps us conceal our mortality, as a provider of leaves concealing our nakedness. We love the good because of what we can do with it. So, the Garden is no longer really good in our eyes. We have thus lost our original place in the Garden, taking our bearings from means, rather than ends, or projecting ends into a realm of possibilities presupposing the actuality of means.

The same problem emerges mutatis mutandis in Dante’s Inferno, where residents are met hiding, apparently from punishment, unaware of their fault. Indeed, Dante meets some of his dearest old friends who do not betray any consciousness of their fault; nor does Dante bother reminding them of any fault. Might they be where they are in spite of themselves? Could a snake have been responsible for placing them where they do not deserve being? No more than Job deserves being tortured, or Jesus crucified? Is Adam expelled for our sake? Because he had seen what God sees? Is God jealous and thus like Adam’s children? What alternative understanding might the Bible invite? What is wrong with seeing as God, or seeing without “protective gear”—as if in outer, deep space where no atmosphere envelops us? God had said that the Garden was good, not good for something else. Man was meant to recognize the Garden as such, independently of evil or of the problem of evil. Yet evil is always lurking; a window of opportunity is always open to it in the very midst of the good—as both the Bible and Virgilian paganism remind us—as a snake in high grass (latet anguis in herba).[2] The Garden as such is not enough to escape from the threat of evil. Human intervention is needed; man must learn to partake in divine action.

Adam’s Fall signals that escape from evil is only guaranteed through art mediated by God’s original logos, logos we must plunge back into as a way of life and truth itself. This logos is key to the artful way of life leading back into the infinite depths of the logos. Art and divine discourse together save us from falling into a bad or wrong place, a place where we can no longer be ourselves, or where our freedom is considered a sin. To tie our art back to God’s own logos or “Way” is the work of human logos, or the presence of the divine in human art. That is none other than Dante’s own poetry, an enlightened poetry that is at once philosophy properly understood: not love of wisdom through the serpent’s devious talk (means distracting from the good), but love of wisdom as end in itself—not of wisdom as a stepping stone to eternal life, or to escape from death.

Dante’s logos shows us that our primordial desire is not sinful, or that desire for wisdom is not antinomian. Adam did not sin out of his own hubris, for he had none; nor was his error seated in Eve’s senses, in which evil merely reverberated. Evil is seated in the serpent, or is manifest through the serpent, repository of possibilities transcending human determinations, or human naming. The serpent exposes us to what falls outside of our jurisprudence—the unforeseen and essentially unforeseeable. The serpent is then the anti-Christ who incarnates the possibility of evil, just as the Christ incarnates the possibility of redemption from evil, which is to say, the possibility of integrating evil within the Garden of good things. Only God can redeem evil, for only He can make good use of it. What is evil, here? It is the amorphous material that God orders into what deserves to be called good. In its primary sense, evil is not a determination, then; evil becomes a determination only through the serpent, or where man tries to integrate the indeterminate within the determinate; when man attempts to “redeem” or domesticate the unlimited. Man’s failure is signaled by the Fall of an Adam who had accepted unreflectively the counsel of relatively independent senses. Divine involvement in logical reflection would have spared Adam all rude awakening to his nakedness. Similarly, by letting the divine intervene in the use we make of sensory data, or by exposing philosophy to divine transcendence, we complete philosophy, or philosophical poetry: we perfect Adam’s effort to integrate evil into the good, which is to say, to use the indeterminate as a “providential” opportunity for good.

God’s intervention as mediator of knowledge of both the Garden and divine indetermination appears as a punishment to an Adam who, having faced death as evil and having thereupon concealed his mortality, fears being unmasked by God. He senses that God sees behind any and all mask, risking to expose what Adam does not bear to face. Indeed, Adam is not mistaken. Not only does God see him naked behind his fig leaf; what is more, God banishes Adam from the Garden of unmasked goodness, to “fall” into a world in which all goodness is mediated by masks (as all ends, by means). There, however, the art of “masking” is blessed by God, who provides the first sown hides for Adam and his companion to wear. Yet masks seem to presuppose a name. So, prior to God’s clothing her, Eve is named by Adam. It is perhaps in view of clothing, or the art of clothing, that Adam first names his equal, Eve. Adam is apparently done learning how to name inferior animals, even though he does not yet appear fit to name superior life forms. Be that as it may, language remains of the essence for art, or human life.

There is something profoundly heroic about the life God calls Adam to live. The Garden’s snake obscures divinely inspired heroism by luring us to embrace a surrogate form of heroism, an atheistic “heroism” aiming at reducing divine indetermination to the determination of a “new man” beyond (the distinction between) good and evil, a man who has established a “garden” without borders, a world embodying all that transcends it, a realm integrating all threats, all enmity, into a single, totalizing art—a mask that points back to itself as consummate truth.

The hypothetical upshot of the serpent’s crafty manipulation of man invites the thought that the Bible’s God condemns the serpent for having used Adam’s reason to conceal truth, thwarting, if only for a moment, God’s effort to raise man’s reason to partake in, to “breathe” or live truth—between life and death, between good and evil as the possibility of the good’s loss.

Man is given the good, but also the possibility of losing it. It is faced with that possibility, with the problem of losing the good, or with the idea that he might err, that Adam desires art; it is only in the face of death that man ultimately turns himself into a mask, recognizing his own life as his own art. Man’s supreme calling is to conceal death (indetermination) for the sake of mirroring the eternal as creative, providential agency essential to all art, above all the art of creating our Garden. Contrary to what Eden’s serpent seems to imply, the eternal is not indifferent to the constitution of the Garden, or to the determination of all good things. That is why the “heroism” the serpent invites must be unjust: in placing us on the path to establish a new garden, the snake obscurs the original meaning of our being “placed” in the Garden; he distracts us from the original meaning and goodness of place—of being-somewhere, of determination.

How is the heroism invited by the biblical God related to the painter’s effort to convert the Low into the High, the “vulgar” into the “sacred”? The painter shapes a shelter for our mortal eyes in the face of an otherwise blinding totality. The shelter tells us that eternity is the ultimate creative source or provider of the shelter, reassuring us that our proper place is a Garden that does not risk being burned down by unforeseen dangers (Dante, Inferno 2.91-93). The painter would then be somehow rehearsing the creation of the Garden, of the world “prior to” man’s fall into a valley of death. The painter’s proper task would not consist in “describing” or “illustrating” the Garden, but in mirroring it—inviting us to turn back toward it, to discover its rootedness in eternal, divine indetermination. In order to see the Garden as good, we need a painter sheltering us from the blinding effect of divine light. Between divine light and blindness, as between Apollo and Icarus’ demise—between salvation and perdition—the painter discloses (and thus exposes himself to the discovery of) a heroic middle, the place defining man as man. That place is a poetic Garden between light and dark, a Garden of penumbra presented, however, not as a mere derivative synthesis of light and dark, but as original key to both light and dark, or rather to their distinction. For the painter is not merely using light and dark to raise the Low unto the High, i.e., to humanize the sub-human. The painter as such discovers, or makes an effort to discover, penumbra as the heroic/poetic place where the “low” is restored to its original (human) dignity and irreducibility. Penumbra is an underlying problem the painter can access beneath the apparent conflict between light and dark, between the divine and death.

It is by diving, in the medium of logos, into death as the indetermination of matter/nature, that the painter can discover the divine, not as a blinding force above the human, but as that mysterious penumbra in which Dante evokes his “Castel of Nobility” (the nobile castello of Inferno 4)—the penumbra of the divine partially hidden within the properly human (i.e., ethics), or of God as the truth about Man. Penumbra, then, stands for the original revelation of the divine, as the place where the divine shows itself in the act of hiding and indeed as that which hides by its very nature and that, in hiding, shows itself.

No painting announces the heroic encounter of man with the divine more brilliantly than Raphael’s School of Athens (1508-12), not ostensibly a heroic painting, but a prophecy of heroism: Raphael’s fresco stands to heroism as John the Baptist stands to Jesus; in pointing to heroism, Raphael does not yet point to what heroism points to—to what stands behind the Cross, as it were. Not altogether unlike the Saint Francis depicted in Jacomo Pontormo’s 1516 Pucci Altarpiece, Raphael evokes truth as an image: his gaze is turned to heroes, rather than to what heroes see, even though Raphael does not remain altogether under the dominion of an image—for the image he turns to looks back upon the viewer, as the child looks back upon the maternal eyes that nourish him.

Even in his final work, the Transfiguration (1518-20), Raphael paints heroism without being fully heroic: he does not yet discover penumbra as key to the tension between light and dark. Instead, not unlike one of his painting’s characters, Raphael points to the Christian prototypical hero, who, in turn, looks further up. To be sure, Raphael does not invite us to look upon the “resurrected” guise of the hero; indeed, the painter warns us that, qua image, the truth about the hero is blinding, so that it can be contemplated only as something otherworldly: the only two characters seeing it without being blinded are lifted above death, or into the heavens, as carriers of religious doctrine—in one case, Mosaic Law, in the other, the Gospels. For, the hero having risen above death is the consummation of all religious discourse.

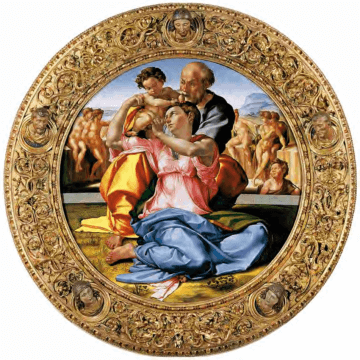

There is nothing “Romantic” about Raphael, insofar as he looks upon the heroic, not as an answer, but as a question inviting us to be, ourselves, heroic, in the classical, Platonic tradition. Raphael’s paintings are invitations to heroism, even if they are not yet heroic, themselves. They do not rise to the heroism of Pontormo’s 1525 Supper at Emmaus, which invites us to look upon the “Eye” hidden “geometrically” behind the Christian hero. The real subject matter of Pontormo’s painting is vision, not as a fixed element, but as a path: vision as the heroic path to truth. We are invited, not to stare in passive contemplation as an unarmed Jesus—who is staring at us, viewers—but to penetrate into the “bread of life,” armed, as it were, as the only character of the painting who turns in the direction of the geometrically inscribed divine Eye. For Pontormo, the blessing of the bread, or of nature, stands only as preface to the cutting through nature, the “aesthetic” penetrating of nature to discover providential vision, therein. As in the case of Michelangelo’s Tondo Doni (1506-07), Pontormo orients us specifically towards the Ideas standing behind divine images—even as in Michelangelo, the characters or personae do not yet look upon us to testify to the painter’s own presence.

While in both Michelangelo and Pontormo the agency of the painter is key to any adequate understanding of divine forms, Michelangelo’s Christ—that of the Tondo Doni, no less than the Herculean one of the Sistina’s Last Judgment—remains too lofty, too “Platonic” to deign to look upon mere mortals. Pontormo’s Jesus is not worthy of imitation. Divested of his Apollonian allure, he begs the viewer to achieve what the Christian persona is said to have achieved. Whence the Pucci altarpiece’s intimations: young Jesus, Mary and St. John the Baptist, are well aware of their theatrical context, inviting us ironically to turn beyond the painting, to an agent that is, however, not yet heavenly, as in the case of Botticelli’s paintings.[3] Compare Pontormo’s alterpiece, where Mary points to what Jesus sees, to Botticelli’s Calumny of Apelles (c. 1495), where Beauty (as the painting itself) points upward to ethereal truth. With Pontormo, truth is no longer ethereal in the sense that it does not hold the prestige it holds under the Medici. Botticelli’s sylva (Politian) or “Garden” (most notably the so-called Primavera) is exposed as radically theatrical, or poetic: even the divine (biblical) justification of the painter’s creations is framed by poetry, thereby acquiring an ironic character.

In sum, Michelangelo and Pontormo are both heroic painters, while Raphael may be considered a proto-heroic painter. As for Botticelli, heroism is still dependent upon a political regime; whence, for instance, the role of the painter in the Calumny (not to speak of Botticelli’s other paintings’ various references to the Medici), or Mercury’s turning (in the poetic “Garden”) to the heavens as enlightening mirror of political things.[4] Botticelli’s hero is still naked, “exposed” in his fragile decorum, as a crystal gem, too pure to be armed as will be Pontormo’s hero, or Pontormo himself, who has descended from Michelangelo’s Platonic heavens to set the stage for politics or public discourse itself. Pontormo makes no concessions to Botticelli’s vulnerability, since for Pontormo the hero is no longer exposed, but hidden, if only at the heart of human things. He stands on safe grounds. Whereas Botticelli projects himself in his paintings, or, to be more precise, in the beautiful aspect of his paintings (as poets do in their muses), Pontormo conceals his hero as backstage director, leaving the stage bathed in ambiguity: the painting is no longer the “Garden” Botticelli painted in Dante’s footsteps, a place where the painter thrives, if only by testifying to the injustice he endures in the “outside” world (outside of Parnassus); Pontormo’s painting is the place where the painter hides. Whence the “ambiguity” of the stage; a stage dominated by heroic penumbra, the painter’s preferred hideout.

Pontormo’s penumbra is not, to avoid misunderstandings, the product of a strategic mixing of colors, but the manifestation of the painter’s heroism, the painter’s consummate discovery of the divine through his effort to resolve the riddle of life and death, the tension between God’s eternal life and our mortality. As a painter, Pontormo has dived into the realm of the dead (nature) in search for the Ideas (the divine hidden in man) that he could “draw out,” thereby translating them into a painting, a symbolic repository of divine forms. But as a full-fledged heroic painter, Pontormo has achieved more; for, having found the Ideas (not merely reacting to Ideas discovered by others), the painter has “hidden” them in his paintings, or in the “mirror” of the paintings’ enigmatic penumbra. The painting is not merely echoing divine Ideas, for the Ideas themselves have entered into the painting through the logos. Otherwise put, the logos has succeeded in restoring Ideas at the heart of human life and order. Yet, the logos is none other than the natural articulation of Ideas, inviting us to conclude that the Ideas themselves have journeyed logically into the heroism that provides for civilization in the face of all loss thereof. With Pontormo, the Ideas have become the painter’s own virtue as enshrined in its painting.

It is true that Pontormo calls us to rise outside of the painting to his own heroism, but that heroism, that “outside,” is right beside the painted scene, as its immediate backstage, allowing the painting to bespeak heroism: not merely to announce its “coming” (Raphael), but to “ironically” (Socratically) pronounce its mysterious lingering, its half-concealed presence. The painter is present within the painting as God is within the Garden of Eden.

What makes Pontormo’s “innovation” possible is his actual encounter with divine Ideas (“the light shining the dark”) as the original seat of the human, or as the painter’s birthplace, his “natural place,” his homeground. The discovery of the Ideas in the depths of death is none other than the discovery of man as the problem of everyday life, par excellence. What Pontormo discovers—or what discloses itself in Pontormo—is the permanence of the human in the empirical world and thereby the impossibility of any world—of any garden—aside from the human. Thereupon the painter emerges as unassailable philosopher, having transcended his dependency upon philosophers’ opinions, including the best of them. As Dante himself had invited us to do, Pontormo rises from the image of Ideas, back to the Ideas themselves, in the medium of logos. He is no longer vulnerable (Botticelli); for he no longer hides within heavenly Ideas, or on Parnassus, exposing himself to being displaced by some unforeseen forces. The heroic painter has “descended” in our midst to take up the role of “director” of our common walk of life; Pontormo is now the living symbol in which the Ideas themselves (our permanent problems) converge to speak and in speaking create and govern the stage of human or political things. In sum, Pontormo discloses our world as the painter’s own theatre.

Pontormo’s heroism entails, then, the surfacing of the painter as noble repository or living symbol of eternal forms: the painter is no longer merely the student of Ideas (Botticelli), but the site where Ideas speak, defining the contents of our world, which is to say, ordering sensory indetermination into a “garden,” where everything may be said to be good. Thanks to the painter, the world is purged of all evil, not because the possibility of evil has been banned, but because the painter presides over that possibility, guiding our freedom into a poetic context, to purge or convert it into virtue.

Figures

1. Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (detail), 1490-1510; 2. Raphael, School of Athens, 1509-11; 3. Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci), Pucci Altarpiece, 1516; 4. Raphael, Transfiguration, 1518-20; 5. Pontormo, Supper at Emmaus, 1525; 6. Michelangelo, Tondo Doni, 1506-07; 7. Michelangelo, Last Judgment (detail), 1536-41; 8. Botticelli, Calumny of Apelles, 1494-95.

Notes

[1] ”Il secondo parlare, che risponde all’Età degli Eroi, dissero gli Egizj essersi parlato per simboli; a’ quali sono da ridursi l’Imprese Eroiche; che dovetter’ essere le somiglianze mute, che da Omero si dicono , i segni, co’ quali scrivevan gli Eroi; e ’n conseguenza dovetter’essere metafore, o immagini, o somiglianze, o comparazioni; che poi con lingua articolata fanno tutta la suppellettile della Favella Poetica”.

[2] Virgil, Eclogue, 3.93.

[3] Joseph and John the Evangelist turn their gaze to that which Jesus sees, yet, unlike Mary, Jesus and John the Baptist, neither man is smiling. John the Baptist, in particular, turns to Saint Francis ironically suggesting that he should look beyond the image of Jesus.

[4] See my lecture “The Symbolic in Painting” (01/29/21) at <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pw1GoLI9YmI&t=3873s>