The Alcibiades of Our Time

We now have two presidential candidates each appealing to their bases with head-fakes to an ever-diminishing center. Donald Trump has tapped into the political, economic, and cultural discontent of the white working class who are tired of the condescension and contempt of our elites, while Hillary Clinton had her own conversion to Bernie Sanders on the road to Philadelphia, not to mention to her call of identity politics to be the first woman president, a call reminiscent of Barrack Obama’s 2008 campaign of being the first African-American president. With the slicing and dicing of the electorate and the micro-targeting of voters for the past twenty-five years, presidential elections are no longer about mandates to govern but rather schemes about turning out one’s base and the demoralization of the other to win. Instead of deciding what constitutes the common good for the country, presidential elections have become emotive exercises of self-expression for the candidates and their voters.

The public’s dissatisfaction with either presidential candidate goes beyond the corruption, lying, and lack of character in Clinton or the cluelessness, misogyny, and racism of Trump: it reveals the limits of identity politics as such where appeal to one’s own is not enough for the body politic to function. One hears in conversation, “because my identity is X, therefore I support Y,” as if this were sufficient to be an argument in and of itself. But instead of pointing out the logical consequence that if you are not part of a particular tribe, then you no longer care for its members, most Americans, at least among our elites, kowtow before the gods of multiculturalism, nodding in silent affirmation because they have been taught to feel guilty and atone for their ancestor’s sins. Instead of partaking in a genuine conversation about the common good, our political elites and pundits speak only to rally their own members and intimidate the opposition. The result is that our public institutions are discredited, perceived as only a partisan tool for those in power and where our citizens apply arbitrary, ideological litmus tests to them to see whether they are worthy enough to join (e.g. the anti-vaccination movement; the privatization of our prisons, law enforcement, and public education).

This loss of faith in our public institutions is illuminated in today’s popular culture, the substitute of parents in the rearing of our children. A recurrent theme in recent television shows and movies is the fetishization of the family and how this value triumphs over all others, even political ones. Traitors, spies, and criminals are excused for their behavior because a family members was held hostage; it becomes understandable that presidents, politicians, and generals to sell out their countries because their children are at risk. But this failure to put the political over the familial prevents the possibility of public sacrifice, when citizens accepts the tragic outcome of their personal lives for the public good (think of the last time you were asked to sacrifice anything by our political elites). The ethos of a shared sacrifice has been replaced by right-wing libertarianism and left-wing statism where citizens believe they can do whatever they want or be micro-managed by the mandarin class. Tribalism has triumphed over public values: what matters more today is loyalty to one’s own rather than persuading others for a common cause.

Our two presidential candidates, Clinton and Trump, are the epitome of this new code of conduct among out elite, with both putting their private fortunes ahead of the public interest. Despite her rhetoric of caring for the country, Clinton’s actions of paid speeches and pay-for-play foundation make any of her statements about the public good laughable, even though the media does it best to portray it otherwise. And when her intention is genuinely exposed, Clinton resorts to a Nixonian paranoia of blaming right-wing conspiracies and anti-feminism forces to rationalize her actions. By contrast, Trump does not even attempt to hide his self-interest at the expense of the public good; instead, he makes it the centerpiece of his campaign in a weird and strange way of elevating it as a virtue for him to be elected. He and his followers fail to recognize that being good at business (i.e., pursuing one’s interests) does not equate into being good at politics (i.e., pursuing one’s interest and the common good at the same time). And yet millions of Americans have ignored the Aristotelian dictum and have supported him.

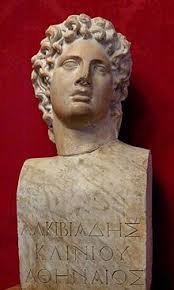

Regardless of who wins the election, the fundamental trajectory of our country will not change with elites enriching themselves at public expense. Clinton and Trump are the latest manifestation of a string of presidential candidates in the past twenty-five years who put private interests ahead of the public good. Our elites have become the Alcibiades of our time, the fifth-century prominent Athenian statesman, orator, and general whose talent, ability, and promise led him to the highest offices only later to be ostracized because of his ambition to gain wealth and reputation by any means necessary. After his expulsion, Alcibiades worked for the highest bidder – Sparta, Persia, and Athens again – to further his own ambition and glory. He was a citizen of the world, a cosmopolitan, whose interests appear global but in actuality were entirely parochial. From Bill Clinton to Hillary and from George W. Bush to Trump, we have had a series of presidential candidates whose ambition, ability, and connections have led them to pursue their private pursuits in public office.

However, our elites recognize that to say such things is too stark for themselves and the public, so they dress up their desires as a type of cosmopolitan idealism (Clinton) or nostalgic patriotism (Trump). Yet they can claim these ideologies not because they necessarily believe in them but to protect their own interests, for, at the end of the day, they are insulated from the consequences of their own actions, whether it is free trade agreements that destroys our manufacturing base, relaxed immigration rules that drive down wages and leads to a disregard to the rule of law, or a social agenda of diversity that only exacerbates our country’s racial and ethnic conflicts. It is our elites’ belief that the free flow of labor, commerce, and capital, along with an ethos of human rights, multiculturalism, and political correctness is good for the world under their leadership, even if it hollows out and culturally excludes our middle and working classes.

This presidential election has shown that the traditional ideological divide between left and right has now been replaced by globalists or cosmopolitanism, on the on hand, and localists or parochialists, on the on other; or, to use the more prejorative and media-preferred terms, open and closed. Those who belong to the former camp are elites who favor globalization and multiculturalism; those in the latter are the working class who are patriotic and culturally particular. The class that holds the center, the ever continually-shrinking middle, aspires to be globalists but fears that they will become localists. The result is perpetual conflict with each side waging war against the other in the belief that their party represents the true America.

Whether this new ideological division between globalists and localists will hold take root will probably take another fifteen years to see. But if the globalists are successful, the political implications for democracy is troubling, for globalists claim to know what is best for people – after all, they represent the world’s interests and what could be more noble than that? – even if the people do not want it. And when non-elites disagree with globalists, they will be labeled as morally unworthy (i.e., racist) and therefore excluded from any political process.

This globalist ethos pervades our elites and institutions today, especially in higher education where universities have become paradoxically both globally-ambitious and insularly undemocratic (e.g., the trend of setting up campuses overseas while denying due process for students at home). Given this situation, we should not be surprised that two-thirds of young people in the West no longer think democracy or civil rights is an essential factor in where they would want to live.[1] This openness to authoritarianism already has been primed in them by our education system that does not permit dissent and promotes cosmopolitanism and by a popular culture that values tribal loyalty and rejects shared sacrifice. The rise of popularity in the ideologies of libertarianism and statism is the logical outcome of such a culture. Without a shared moral language, which makes people open to persuasion to partake in the common good, cosmopolitans like Clinton will continue to rule as a type of self-entitlement only to be resented by localists.

By contrast, Trump represents the democratic grievances of localists in wanting our elites to be accountable to us instead of the Hague or Harvard; but the solutions he offers are not serious policy prescriptions and marred by his divisive and misogynist remarks. He has tapped into the resentment, even the rage, of the governed but does not offer anything than anger. What localists require is a candidate that can articulate a political vision that is grounded in a realism that holds our elites accountable while providing for the common good of this country; otherwise, globalist rule will remain, as it has for the past quarter century and the cycle of ideological division, voter mobilization, and lack of mandate to govern will continue. The country needs someone other than an Alcibiades to be our leader, if we wish to avoid the fate of fifth-century Athens. Who that person will be and whether we as a country are capable of cultivating one remains to be seen.

Notes

[1] Roberto Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk, “The Danger of Deconsolidation: The Democratic Discontent,” Journal of Democracy 27.3 (July 2016): 5-17. Also available at http://www.journalofdemocracy.org/article/danger-deconsolidation-democratic-disconnect.