The Anabasis of Michel Serres: Hermes-Trickster Knowledge and the Ambivalences of Modern Communication Technology

A Preliminary Remark

The background story to this article is not so different from that of my article published on November 1, 2020 in VoegelinView, not told there. There, the article was commissioned for a special issue of a journal – let the veil of forgetfulness fall over its name. The guest editor, a Canadian sociologist sympathetic to the work of Voegelin – thus, a rare one of its kind – much liked the article, and it was accepted for publication. However, in the meanwhile he got sick, could not finalise the issue, the editors changed, and the new editors surgically removed just my article from the special issue. Here, the article was again commissioned by another journal which also commissioned a review on one of my recent books, even asked me whom I could suggest doing the review. Then, here again, the editor changed, and though I even made the – minor – revisions required for publication, the new editor simply and repeatedly failed to reply to my correspondence, just as it happened with the author of the review. All this is just another sad indication of the current state of academic-intellectual life, where due to a combination of ideological and actual-political reasons not just academic principles, but even the minimal degree of courtesy is disrespected. Having been born and raised in Hungary, I’m not new to such developments, but we should not let unchecked, in so far as it is in our ability, the increased sovietisation of our world – not to use a stronger word.

It remains to be argued why this article, on Michel Serres, should be interesting for the readers of VoegelinView. This, however, I hope, should not be difficult. While I do not know about any direct contact, even a distant reference, between Voegelin and Serres, given the academic conditions of the second part of the last century, this should not be surprising –though actually Serres taught in Stanford from 1984, so they missed each other really just by an inch, just as it happened in the case of Foucault, who gave a talk in Stanford in 1979, but Voegelin could not attend due to sickness. Serres by the way came to Stanford on the invitation of René Girard, who was his life-long friend, and the connections between Voegelin and Girard by now are well established, among others due to the work of Stefan Rossbach.

It is enough to mention three basic facts about Michel Serres. First, he wrote his dissertation on Leibniz, one of the recurrent philosophical ‘heroes’ of Voegelin as well, and there explicitly argued that Leibniz and not Descartes should be considered as the central, founding figure of modern rationalistic philosophy. His reward for such audacity was not missing: he was prevented to teach philosophy, being assigned instead a post in the history of science. Second, apart from championing the thinking of Leibniz, he repeatedly attacked modern rationalism at its core, arguing – just as Voegelin did repeatedly, even against his life-long friend Alfred Schutz (about this, see my review of the Voegelin-Schutz correspondence in the 23 and 30 January 2013 issues of VoegelinView) – that the Descartes – Kant/ Hegel – Husserl lineage is by no means the only tradition in philosophical thought (in order to avoid misunderstandings, this was by no means done in Derrida’s way: Derrida was actually his university classmate and a close friend for a time, but then any reference to Derrida completely disappears from Serres’s life and work). Third, Serres also considered as fundamental for philosophy both the return, beyond modern rationalism, to Antiquity, to classical reason, just as the use of literature for philosophising.

Introduction: Another Philosopher Beyond Contemporary Philosophies

Eric Voegelin was not trained as a philosopher, and many – if not most – professional philosophers in our days would not consider himself as such. Yet, Voegelin insisted on being a philosopher, and in the broader scale of the matter – from where much of what is today considered as ‘professional philosophy’ certainly would qualify as cheap and meaningless sophistry – was certainly right. Michel Serres was by all means trained as a philosopher, and yet the gatekeepers of professional philosophy failed to accept him as such. Hopefully, this article can make it transparent that between their works and ideas there are more than superficial similarities.

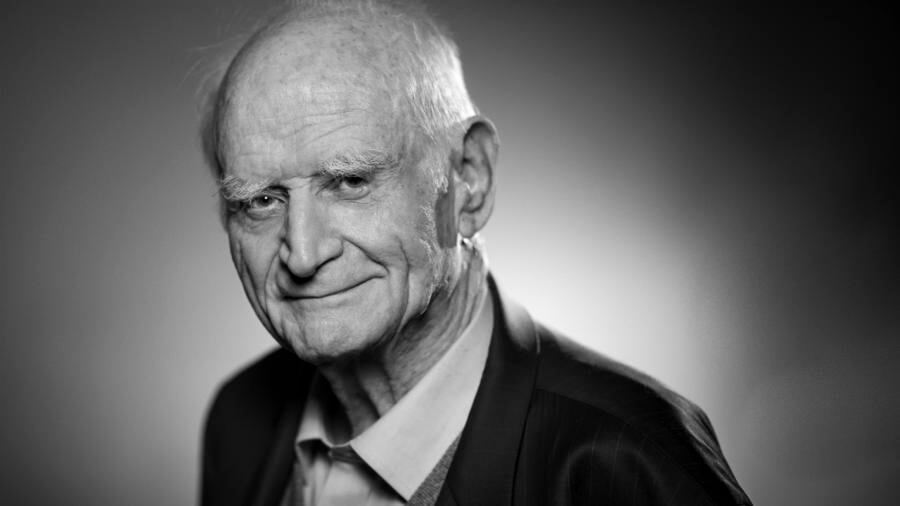

Michel Serres, one of the most innovative thinkers of the past half-century, spent his life in enemy territory, in a both literal and metaphorical sense, thus his life-work can rightly be considered as an anabasis. As he defended his thesis on Leibniz in 1968, also publishing the first of his path-breaking five-volume series on Hermes in 1969, while died on 1 June 2019, his major academic output extended to half a century, during which on the average he published well over a book per year. This is especially astonishing as these books were all quite different, widely adjudicated as difficult to read and digest, and yet also recognised as highly innovative. At the same time, and no doubt having an elective affinity, with such innovativeness, Serres lived most of his life swimming against the currents. Yet, and in spite of this, he did not at all become sour or scornful, rather preserved until the end a genuine joy of life and contentment.

Serres was trained, and always considered himself, as a philosopher, but certainly was a philosopher of a very particular kind. At the heart of his philosophical work was a concern with science, starting from, but not being limited to, the great French tradition of epistemology (Bachelard and Canguilhem). Serres’ interests went beyond the conditions of possibility of science, incorporating thinking science; in particular mathematics and informatics. Such an interest was partly stimulated by revolutionary changes in mathematics, in France associated with Bourbaki, but also the threat of extinction created by the nuclear bomb, which according to Serres amounted to a loss of innocence or ‘original sin’ of Western science (Serres 2014b: 171, 179).

Serres’ uniqueness within philosophy was underlined by two further features of his thinking that were not self-evidently compatible with his interest in philosophising science. On the one hand, and not only in contrast to most contemporary professional philosophers, but even more scientists, he had a great interest in classical Antiquity, frequently referring to antique authors, and considered Lucretius as all but advancing major scientific discoveries; on the other, in his philosophical work extensively used literary sources, arguing that the separation between philosophy and literature is artificial, untenable. One can easily understand that philosophers had difficulty in taking seriously somebody who had impeccable professional credentials but regularly and almost interchangeably used mathematical and scientific theories and models, antique authors, and figures from plays, novels or tales. Even further, while few would accept such a perspective as being philosophical, Serres considered that this is real, lived philosophy, instead of what is being taught as philosophy in most philosophy departments – a point shared with Pierre Hadot; and had no problems in remaining alone, outside both fashionable and establishment circles, having as close intellectual friends only René Girard (who however was not a philosopher) Michel Foucault (not a conventional philosopher either, but from whom he became distanced in the 1970s), and Bruno Latour (who was a step-disciple), as he refused the conformity dominating academic life – including avant-garde or ‘critical theory’ dissent that in some ways is even more conformist that the mainstream. His work was light-years away from Lévi-Strauss, Bourdieu, Lévinas, Lyotard, or Derrida (who was his exact coeval and for a time close college friend), not to mention Durkheim, Sartre or Merleau-Ponty, the dominant figures of university-stamped ‘thinking’ – but strikingly close to Gregory Bateson, another maverick academic outcast.

Understanding Serres’ life-work requires familiarity with his background, where global history, or the macro-macro, and personal experiences, or the micro-micro, are tightly interwoven, helping to follow similar creative tensions in his ideas.

Personal Background and Anti-methodological Methodology

Serres grew into an environment on which the two world wars left an indelible mark. His father’s family was strongly anti-clerical and republican, but based on WWI army experiences his father not only converted to Catholicism, but came to distrust all social powers, including education, viewing any social advancement as yielding to evil, with the Bible being the only book at home (Serres 2014b: 19-22). Just as importantly, he never discussed his war experiences, refusing to talk about what is ignoble (23). While Serres’s thinking is not religious, he preserved an uncompromising moral stance: he only ever wrote down what he personally considered important and true.

This stance was strongly tested in his university years. While formally receiving the best possible education in a supposed French Golden Age at the École Normale Supérieure, it was also a worst possible formation. This is because the ‘post-war intellectual milieu’ formed ‘one of the most terroristic societies ever created’ (1995: 5). His innovative thinking met not encouragement, rather excommunication: when telling Althusser about the coming primacy of information and communication over industry, he was called a fascist, while his thesis defence with Canguilhem in 1968 turned out to be a ‘tragic moment’ (Serres 2014b: 51), as after he was assigned to teach history of science, not philosophy. Serres was thus not only outside the main political and intellectual currents of post-war France, like Marxism, phenomenology, psychoanalysis or structuralism, but took up a position against most of the classical figures of modern Western rationalism, in particular Descartes, Kant, and Hegel, tracing instead his own genealogy through Montaigne, Pascal, and Leibniz.

Modern philosophy, even social science, is much about ‘methodology’, but Serres has little patience for conventional methods. Charging (neo)Kantianism at its core, he refused the primacy of concept formation, populating his works instead with complex, figurative characters (personnages), taken from mythological or literary sources. These figures, like Hermes, Don Juan, Proteus or Arlequin had the advantage of being widely known, concrete but also complex, through which Serres could express and elaborate his ideas. This recalls the way Max Weber developed ideal-types in his sociological classic The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, considering Bunyan or Benjamin Franklin as steps towards such a spirit, even though Weber was not known to Serres, as for a complex set of reasons he was hardly known in France until recently.

Another crucial methodological tool was his use of language. While refusing to develop concepts, words mattered to Serres, more than for those constructing an artificial and unintelligible terminology. His approach lay through the ‘royal road’ of etymology. He consistently explored the original meanings of terms he found helpful, convincingly demonstrating that the wisdom behind coining words is a primary starting point for any serious thinking, instead of assigning arbitrary meanings to constructs, refusing the structuralist dogma of arbitrary signs.

A similarly striking, though potentially more problematic, methodological device is the importance attributed to algorithms, procedures, and codes. For Serres such techniques are important as they enable connections between concrete and universal, local and global, outside abstract formalisations, divisions and exclusions, and generalising deductions. Such procedures are ‘supple and agglutinant’, having the character of ‘walking one step at a time’ (Watkins 2019; see also Serres 2014b: 85-6). These metaphors are particularly interesting, as they evoke the practice of walking and features of the ‘walking culture’ that existed before settlement and the Neolithic (Horvath and Szakolczai 2018), thus during the development of human language for many thousand years; and also agglutinating languages that build complex word structures around few short roots. Intriguingly, the mother tongue of John von Neumann, developer of game theory and computer programming language was Hungarian, which is agglutinating, and he famously quipped that computer language really should have been based on Hungarian.

However, the problem with algorithm and procedurality is they enable a degree of streamlining and control over individuals that abstract methods and theories cannot achieve, thus – especially if combined with Kantian universalism – produce a lethal, easily totalitarian effect. This is why policy-makers and research funders are so keen about them, and there is something sinister about all this. Thus, if Serres even here foresaw the future, our present, better than others, what he intuited was the problem, not a solution. However, it is not always clear that Serres was aware of this fact.

Here we enter the heart of the problems with his works. Within the limits of this article, only one issue is singled out for attention, though arguably the most important: the communication or information ‘revolution’, and the ‘knowledge society’ forming around it.

The Unperceived Troubles with Communication, Information and Knowledge

While these three terms are central, flagship concerns for Serres, with them he apparently failed to pursue his usual etymological investigation, taking them at face value, though each is revealingly problematic. ‘Information’ evokes an absence of form, similarly to ‘informality’, which strikingly has a range of meaning so different from ‘information’. ‘Communication’ refers to rendering something ‘common’. However, before accepting with Serres that basically anything we do is a ‘communication’ of ‘information’, we need to realise that when two human beings meet, what they do is very different from such a – generalised, indeed over-generalised – vision of ‘symbolic exchange’. Whatever they do, beyond the most trivial layers, is most concrete and extremely personal. We humans, in insurmountable difference from machines, don’t ‘communicate’ with each other, but talk: not simply saying words, but making all kind of gestures, intonations, using our whole body, especially the eyes, as first of all we look into each other’s eyes, perhaps only for a short while, or perhaps exactly do not look at the other, especially not into the eye. Saying that all this is nothing else than the ‘communication’ of an ‘information’ we commit the generalising error otherwise Serres is so keen in identifying and avoiding.

The word ‘knowledge’ is just as if not more problematic. Concerning etymology, it goes back to Greek gnosis, a term used for a Hellenistic sect, also as Gnosticism, which attributed to knowledge the power of salvation – strikingly, not so differently from the modern idea according to which ‘knowledge’, through science and technology, will transport us to an earthly paradise, justifying the ‘modern Gnosticism’ thesis of Eric Voegelin. This is also the problematic vision behind the ideas of Bacon and Descartes that Serres identified in some of his most important early work, close to Foucault’s power/ knowledge, but which he seems to have forgotten in his recent celebrations of the information revolution and the knowledge society – though he also recognised the paradox of ‘communication society’, in that it is also ‘a society of the incommunicable’ (Serres 2014b: 122). Furthermore, Plato devoted a most important dialogue, Theaetetus, to knowledge, which is quite conclusive in its inconclusiveness. We simply cannot take for granted what ‘knowledge’ is, and thus Serres’ celebration of the universal and easy access to ‘knowledge’ due to the communication revolution in Thumbelina simply begs the question, even begs belief. Giving only one further example, and related to the meaning of words, ‘knowledge’ is almost identical to ‘acquaintance’ and ‘familiarity’, yet the semantic horizon of the three words is – literally – radically different.

If the heart of Serres’ philosophical interests is in links between science, mathematics, informatics, and technology, then these converge on his visionary insights recognising the importance and understanding the character of the revolutionary changes taking place in communication technology. Since the first book of the five-volume Hermes series, published in between 1969 and 1980, his work explored the shift from the industrial revolution, symbolically marked by the move from Prometheus to Hermes. However, foreseeing a certain development is one thing; its evaluation is quite another. One can foresee a coming new Golden Age, just as an apocalyptic collapse. The way Serres captured these changes, through personnages like Hermes, the parasite or the joker, was not just uniquely perceptive, but highly instructive. Yet, there were certainly problems with his formulations since the beginning, which eventually, under the brainwashing impact of living for long in Silicon Valley, culminated in the deeply disturbing and untenable philosophy of the contemporary expressed in Thumbelina, which certainly not accidentally, though not for good reasons, became his biggest best-seller.

The full complexity of the point can be introduced through The Parasite, culmination of the Hermes series, and easily Serres’ most important book.

A chef d’oeuvre: The Parasite

The book offers a perfect illustration to Serres’s linguistic methodology. The word has three quite different meanings. First, following Greek etymology, it captures someone uninvitedly eating at the table of the others. The second, most common sense is a small being that lives on and feeds from an animal or a plant. The third, French meaning is undesirable noise, interference, or static electricity. The book is built on the tension between these three meanings.

This section will reduce attention to two questions (for further details, see Szakolczai 2019): what can it mean that communication can be, or is, parasitic? And how can such parasitism have a positive and not just negative sense? Before attempting an answer, let’s review Serres’ series of ‘definitions’.

As ‘best definition’, the parasite is – using the terminology of physics – ‘a thermal exciter’, as it enters the body, infests it, being able to adapt to different hosts, always irritating (Serres 2014a: 341-3). The excited organism inevitably reacts, generating flux, acceleration, inflation, fever, or illness, as health is the silence of the organs (353), a recurring concern for Serres. There is something inevitable in the arrival of the parasite; it produces heat and fire, water, turbulence and liquidity; it is ‘an inclination to trouble, to a change of phase of a system’; its main concern is to ‘transform the state of things (l’état des choses) itself’ (353). Furthermore, the parasite starts as a minimal deviation or écart, example for the ‘minuscule’ so important for Serres (Serres 2014b: 79-80, 89), but which under certain conditions, which we would name ‘liminal’ (a term not used by Serres), can grow until it ‘transforms a physiological order into a new order’ (2014a: 358). A few pages later, Serres adds the insight that every parasite lives by provoking crises (375), or ‘forcing’ liminality.

In light of such views, what is the sense in which communication is, or can be, parasitic? This can be captured in two words, repeatedly used by Serres, ‘relation’ and ‘in between’.

‘Relationality’ is one of the main buzzwords in current social thinking, and Serres is often evoked as one of its prophets, Far from simply praising ‘relationality’, however, Serres rather calls attention to the problem posed by mere ‘relations’. Relations do not have a value, and once deprived of a proper substance and meaning they can easily turn oppressive, even totalitarian, mere stakes (enjeux), fetishes, commodities (Serres 1986: 169-70). In this way, we ‘make ourselves troglodytes of our collectives’, being enclosed in the caves of the media, or the caverns of politics, ignoring nothing else but the world, the realness of reality. Reality, the real world, is beyond mere relations, and is rather concerned with love, beauty, harmony, or grace. This is in frontal contrast with the structuralism of Lévi-Strauss. Such concern with real substances was not just central to his works, but to his life and character – this is why he was considered, and remembered, by everyone who knew him as a man of extreme generosity and benevolence – character traits that, as we are increasingly recognising, are central not only in our private lives, but also for understanding the world, beyond competently manipulating it – as without such character traits competence and efficiency, far from being assets, rather become lethal liabilities, springboards for the ecological crisis through destroying nature, of which Serres was a first diagnost.

A ‘relation’ also implies an ‘in-between’ or ‘liminal’ area that is central both for communication and for the parasite. This ‘in-between’ is an empty space, a void between concrete beings, so has no value, even no reality whatsoever. It is through this space that two beings can establish something ‘common’ between them, ‘communicate’ or ‘exchange’ – assuming that they do not belong already, as parts, to a broader unit in which they participate – though of course they certainly do.

At any rate, it is in this in-between that both communication and commerce can develop, establishing communalities if previously these did not exist. Key terms in both communication and economics literally mean ‘in-between’, like ‘media’ or ‘interest’. We can now easily understand the meaning of a communication parasite: it is whatever that takes up, monopolises and abuses for its own purposes the in-between space of communication or mediation between entities. Filling the space, it first renders direct contact impossible, and then, once the entities became used to its mediating presence, it even makes itself indispensable, arguing, with increasing – though still unnecessary and parasitic – justification that in its absence such entities could not communicate; even could not do anything whatsoever. The necessity of mediation, thus of mediators, is a most pernicious modern ideology, whether in business, technology, politics, or philosophy.

As an easy example, we can refer to the much-dreaded transmission error of TV channels, capturing the utmost fright of moderns about television suddenly stop working – until we realise that we have no need whatsoever to look at its transmission, rendering our lives a slave to it, and so it is much better to switch it off – or, even better, not to have it at all in our home. Serres’ work helps to understand that television, but also personal computers, mobile phone and any other gadgets are parasitic intruders into our lives, interfering with our activities and lives, possibly even altering our character if we are not careful enough, thus we should never give up our guard and consider them as benevolent friends.

This example already moves to the second question, a possible positive meaning of ‘parasite’. Beyond occupying a place in space, parasites might create a new space or modality of mediation. Serres explores a number of different ways how this can be done, by ‘irritating’ hosts or producing ‘interference’, with the result that such parasitic activities can become inventive, innovative, creating something new. By placing emphasis on such creative aspects of parasitism Serres ends up not simply hailing the internet but outright arguing that access through mobile phones to ‘information’ contained on the internet renders books and classical education meaningless. Who needs a professor if one can look up everything instantly on Wikipedia?

Anybody involved in teaching 18-20 year old student in these days would immediately recognise that there is something deeply wrong with such a position, beyond members of vested interest groups (read: university professors) defending their monopoly power. Education, as Max Weber and Tim Ingold argue, is not about transmitting ‘knowledge’, but helping to form judgment. Serres produced an extremely important life-work going beyond the inbuilt Sophistry of modern intellectual life. But this is a far cry from seconding the demolishing of the Platonic academic framework, still a foundation of our culture and civilisation.

What could have gone wrong in Serres? One can easily point to his neglect, even marginalisation by the official philosophical establishment, and also the impact of living in Silicon Valley. As a joint outcome, Serres became too distant to the genuine values of academic learning, while losing the distance with respect to certain contemporary developments – against his earlier realisation that he did not want his children to grow up in the US, in an environment lacking any problematisation of modernity.

Even more, his later position ignored his own The Parasite, still safely rooted in the world-vision imparted to him by his parents. This concerned the widespread presence of evil at the core of modernity, and of being apprehensive about anything ignoble. The Parasite, as he came to realise while working on it, turned out to be a book about evil. There he recognised, in its crucial last pages, that the corollary of parasite power is the resurgence of evil. It is to the unlimited, frenetic activities of the parasite that a number of things are attributed, including rumour, fury and incomprehension, violence and killing, misery and hunger, illnesses and epidemics, and also ‘bestial metamorphoses’ (Serres 2014a: 453). Thus, when finally finishing it, he felt as if a ‘horrible insect [would have] slowly left his room’ (454), alluding to Kafka’s Metamorphosis. A parasite is also inevitably something disgusting and ignoble. A parasite cannot be generous or beautiful; we cannot possibly love a parasite. There is something inherently problematic in arguing the innovativeness and creativity of parasitism.

Indeed, when advancing such claims, Serres’s work reaches a number of evident limits. His championing of Hermes against Prometheus is a masterstroke but – fully in line with the recognition that The Parasite was indeed a book about evil – Hermes is just as ambivalent a figure as Prometheus, so such progress is a mixed blessing. The ambivalence of Hermes was explored by thinkers who – well before Serres – discovered the connection between Hermes and modernity, like Károly Kerényi and Thomas Mann, not discussed by Serres. This is all the more astonishing as Kerényi was a student of classical Greek mythology, while Mann a most important modern novelist, fitting perfectly Serres’ overall methodological approach. Kerényi even wrote a Postface to Paul Radin’s classic work on the trickster, arguing that Hermes was a par excellence trickster figure, but this anthropological term is missing from Serres’ radar, as perhaps he too quickly identified anthropology with the indeed problematic approach of Lévi-Strauss. Ignoring the trickster, so evidently close to Hermes, is not an easily forgivable error, as among others the trickster in many cultures is identified as one who creates by destruction, most helpful to problematise the type of creativity associated with modernity, and which he furthermore fails to recognise as legacy of an alchemic way of thinking having seeped into mainstream European culture. Unfortunately there is no space to explore this absence in Serres, which renders intelligible his problematic praise of metamorphosis, an ideological justification of technology. Even further – and here we need to close the argument – one of the most important trickster figures is the spider, famed for setting up a web or net, casting it wide to catch his victims (for details, see Horvath and Szakolczai 2020). The analogies with the internet, which Serres (2014b: 122) makes equivalent with Leibniz’s god, is self-evident.

In Lieu of a Conclusion

Michel Serres is one of the most important and innovative philosophers of the past half a century, among the first to foresee, with Bateson, both the coming ecological crisis and the replacement of the industrial revolution by a communication technology revolution. While in his more recent works he came to exalt this latter development, his earlier work can help us realise its highly problematic, not just ambivalent but outright ‘evil’ aspects, proliferating the pathological and self-destructive limitlessness propagated by modernity, so well embodied in Don Juan, and ‘apparition of Hermes’ and ‘first hero of modernity’.

References

Horvath, A & Szakolczai, A (2018) Walking into the Void: A Historical Sociology and Political Anthropology of Walking. Routledge, London.

____ (2020) The Political Sociology and Anthropology of Evil: Tricksterology. Routledge, London.

Serres, M (1986) Détachement: Apologue, Paris: Flammarion.

____ with Bruno Latour (1995) Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

____ (2014a) Le Parasite, Paris: Fayard.

____ (2014a) Pantopie, Paris: Le Pommier.

____ (2015) Thumbelina: The Culture and Technology of Millenials, London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Szakolczai, A (2019) ‘A Guide in Trickster Land: Michel Serres’, International Political Anthropology 12, 1: 39-58.

Watkins, C (2019) ‘Serres’ algorithmic universal’, excerpt from Michel Serres: Figures of Thought, https://christopherwatkin.com/2019/09/29/michel-serres-book-excerpt-serres-algorithmic-universal/, accessed 16 December, 2019