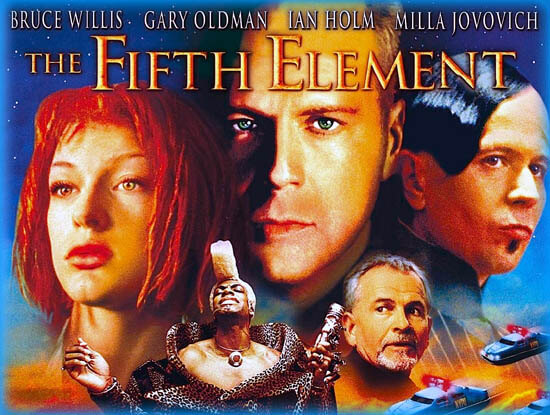

“The Fifth Element”: Unconscious Christianity & Science Fiction

Luc Besson’s now cult classic The Fifth Element gave us a retro-futuristic take on the apocalypse and messianism which was suffused with Christian motifs and symbolism. In my essay “HAL Unplugged,” I mentioned how the 1990s was a decade in which science fiction worshipped at the altar of technology. What made the Fifth Element unique, beyond its psychedelic punk rock and dystopian consumeristic future, was the fact that it challenged the technological fetish of the 1990s and offered that deeply Christian, though eroticized, theme of love saving the world in place of space adventure and scientistic salvation.

The 1990s was a decade of euphoria and liberal triumphalism. The Iron Curtain had collapsed. China was internally liberalizing its economy and becoming integrated into the world market with the anticipatory hope by many of making the great leap into the liberal democratic world. The specter of nuclear holocaust had been lifted off the shoulders of the world. Francis Fukuyama posed the question asking whether we had reached “the end of history.” The apocalypse was seemingly averted; new horizons beckoned.

Looking back on that decade of euphoria, the Fifth Element brought us back to our senses with its gritty portrayal of a future that was hardly worth celebrating. Rather than celebrate an end of history, Besson’s film returned us to even more primal fears of the final apocalypse where a “Great Evil” threatens to destroy all life as we know it.

As the apocalypse approaches, we realize that all the powers of technology and government prove incapable of saving us. A heavenly sent savior, the “Fifth Element,” the “perfect being,” is that which will bring forth salvation from the Great Evil which threatens to consume the cosmos. It is, perhaps unconsciously, symbolic that the film opens in Egypt on the eve of the First World War. Egypt was the land where the infant Christ and the Holy Family had gone into hiding to escape Herod’s tyranny and bloodlust. Moreover, the imagery of Egypt and an archeologist professor trying to unlock the mysteries of cosmic struggle evoke the quests of finding the historical Jesus. The Orient, more than the Gothic cathedrals of Europe or the open-air environments of American revivalism, seem to tap into our psyche of the holy and sacred and give us a sense of the old divine we have drifted extremely far from. The alien, it seems, is always the repository of the mysterium tremendum et fascinans in the modern age—especially when tied to the sands of the Orient.

*

The Fifth Element, like most classic science fiction films, portrays for us certain archetypes, tropes, and narrative progressions that are common to the sci-fi genre as a whole. We see technological alienation and tyranny, the tyranny of technology (and corporatism) especially represented for us in Gary Oldman’s Jean-Baptiste Emanuel Zorg. Moreover, there is a relationship between technology and militarism in the film; Zorg as a “great” industrialist is also a “monster” who profits on destruction and war. We also see the struggle for love and love’s redemptive and salvific spirit in the two leads, Korben Dallas (played by Bruce Willis) and Leeloo (played by Milla Jovovich). The theme of love as the salvific fifth element also manifests the apotheosis of Korben Dallas from the distraught, alienated, and often angry individual he is initially introduced as into a being-for-others. While not uncommon to sci-fi, political incompetence and corruption are also major themes in the film but we will largely pass over this third leg in Besson’s film; but before doing so I would stress the truth of what Besson portrays in this third part of the troika: politics cannot save us as the film bluntly shows.

The sacrificial savior and sacrificial salvation is one of the enduring images of closure in science fiction filmography. While The Fifth Element doesn’t portray this undeniable religious impulse for us, what it does portray is the centrality of love in entering our corrupt and fallen world (Leeloo), love’s relentless pursuit by political authorities (the police chase), and the role of love in human salvation (principally through the union of Korben and Leeloo at the end of the film). Immediately, we can recognize the unconscious—though admittedly eroticized—Christian inheritance moving the film’s narrative to its conclusion. The Fifth Element doesn’t rely on the instruments of science and technology to save us. Those instruments only bring us closer to annihilation. Instead, it is the theological-anthropological reality of love—the “perfect being” and the “fifth element” beyond material things (earth, wind, fire, and water)—that brings forth the world’s redemption and salvation. Redemption through love, as any student of religion, theology, and philosophy knows, is a deeply mystical and religious belief.

Additionally, and perhaps befitting Besson’s Frenchness (and therefore, by genealogical inheritance, his cultural Catholicism), The Fifth Element also insists that the Divine needs man’s assistance. Korben, after all, must come to love Leeloo and show Leeloo that humanity can love and is therefore deserving of salvation. What wounds Leeloo, as what wounds God in the Bible, is unfaithfulness that leads to war and bloodshed. Is life worth saving when all humans do is engage in fratricide and genocide as Leeloo tells Korben? What is good in this world that is worth saving? Love. But Leeloo doesn’t know love and must come to know love through Korben’s intimacy and union with her. The divine’s relationship with man, in the film, through our in-situ archetypal representatives (Leeloo and Korben respectively), is unmistakably Catholic in spirit.

So the film moves to the only conclusion it can reach—a conclusion, common in much science fiction—that only love can save an imperiled world and that love, not science, not technology, not brute force of will, makes two separated, alienated, and isolated beings one in unity. The implicit metaphysical—indeed, even theological—implication of this is drawn only from the Christian tradition. While there is a certain strand of Neoplatonism which can claim a distant second place in this notion that love brings two things together in unity, even in Plotinian Platonism (the very type of Platonism that influenced the Church Fathers and the Christian tradition) still sheds away the material and the earthly in its ascension to the Transcendental One. It is the human to divine ascent that guides the Neoplatonist who sheds his earthly trappings from the pure transcendence of the spirit.

The Fifth Element, however, more vividly portrays the Biblical alternative: Perfection’s coming into the corrupt and fallen world and affecting the union of two becoming one in love while also suffering in the process. Korben must profess his love for Leeloo and, in doing so, help a beleaguered earth and humanity in the face of destruction. The love that Korben has for Leeloo has consequences that extend far beyond themselves. Their love touches the whole of the world.

*

This brings me to another point concerning Christ-figures, soteriologies, and love in science fiction more generally. Whether the myriad of films I have discussed in other essays—from The Day the Earth Stood Still to Star Wars to Interstellar, to name a few—we find deeply religious, theological, and, indeed, Christian themes permeating through them. There is a corrupt or dying world; this world has fallen so far from its ur-paradise and this fallenness has wrought alienation to our main characters. This, of course, is lifted straight from the traditional Christian understanding of the Fall of Man.

Then there is the cataclysmic, apocalyptic, event that waits on the horizon. Whether “the Great Evil” or a meteor or some technologically advanced alien species, Armageddon is near at hand. The impending destruction of the earth, and therefore humanity, necessarily leads to the question of salvific deliverance.

Concerning salvific deliverance, science fiction often moves in two directions—though, sometimes, these two routes are mutually tied together. One route is through sacrificial salvation where the lead character, or characters, engage in some act of sacrifice on behalf of the common good and humanity which permits life to flourish because of the act of sacrifice. From darkly powerful and profound films like Godzilla and Twelve Monkeys to cheesy action-entertainment sci-fi like Armageddon, sacrificial salvation has become one of the reliable hallmarks of science fiction filmography. The other road taken to bring forth the act of salvific deliverance in science fiction is redemption through love. In redemption and salvation through love, two characters so far apart when introduced are brought together in a union of two become one—and in that union through love their love brings deliverance to the world in peril. It is this second route that The Fifth Element takes and portrays for us.

Lastly, there is a generally aversion toward science and technology—the ideology which we might now call scientism—as being good for us. On the contrary, science and technology are often portrayed as threats to humanity and to love more specifically. Science and technology, united in its unholy spirit of militarism (whether, in some cases, human; or, in other cases, aliens), serve as the dark and demonic forces bringing death and destruction to the world or even the cosmos. Science and technology cannot confront the superior techno-scientistic spirit of death that guides much of science fiction. In fact, in The Fifth Element we learn this through the use of missiles launched at the beginning of the film which only enlarge the Great Evil and through the Great Evil’s alliance with Zorg, a techno-industrial capitalist who destroys. Even in films where science and technology play a positive role in humanity’s deliverance (like Independence Day, Armageddon, or Interstellar), it still takes an act of loving sacrifice to complete the deliverance of humanity from what threatens it.

*

The Fifth Element is not a consciously or explicitly Christian film. That is not the contention I wish to make. I would say, however, that a close deconstruction of the archetypes, imagery, and narrative arcs that move the film, reveal unconscious Christian elements to it. Only in a culture once steeped in the religion of love is love the “fifth element” that saves the world. Only in a culture once steeped in the religion of love’s entrance into the material world is this narrative retold (however fancifully, and erotically, reimagined as it is with Leeloo). Only in a culture once steeped in the religion of love as binding two together as one is this notion of love repeatedly utilized (as witnessed in Korben and Leeloo’s union). Only in a culture once steeped in the religion of salvation through sacrifice is this enduring and eternal image used over and over again to bring an act of salvific deliverance to a troubled world.

For whatever faults one might find in The Fifth Element, I would hope that another look at the film can reveal something mysteriously enchanting about it. The basic narrative movement of the film relies on Christian themes and realities. And with the veil torn back and sacristy of the science fiction genre open to us, we can begin to see the Spirit of Truth still percolating through it. There remains, even today, in our increasingly “secular” and “secularizing” world, an unconscious inheritance that still points back to the Incarnation and to that hill at Calvary.