Unfallen Joy and the Tragedy of Love: “Waterloo Bridge”

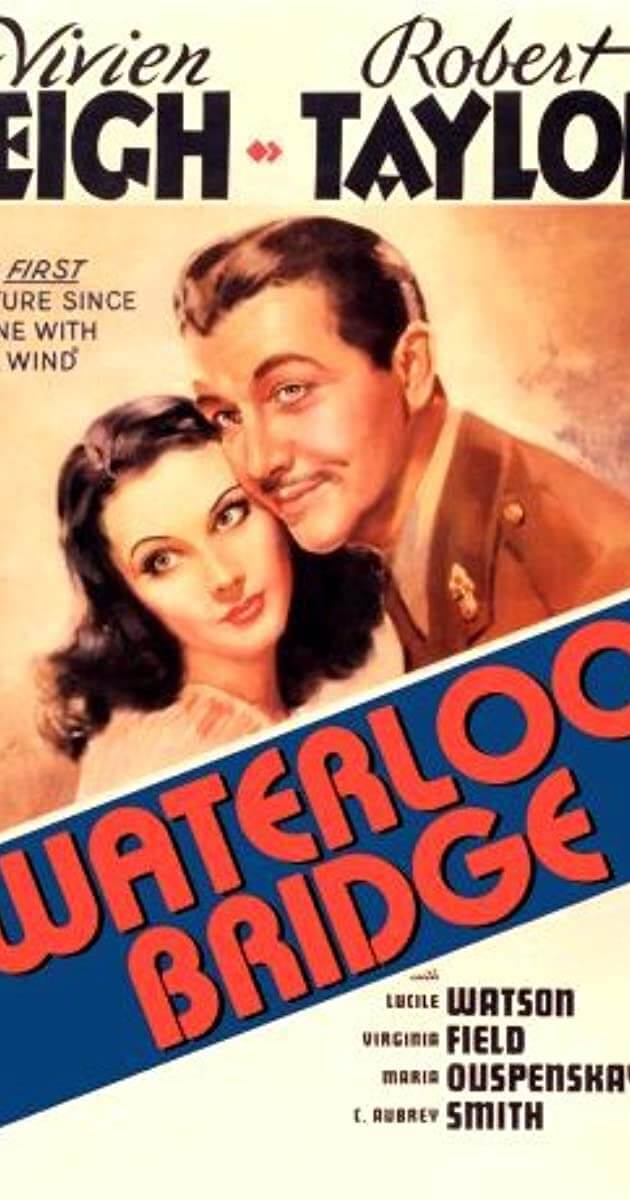

The 1940 MGM adaptation of Waterloo Bridge is one of my favorite films. It stars Vivien Leigh, in the wake of her Gone With the Wind fame, and Robert Taylor, then a rising star in Hollywood. The film deviates somewhat from the play of the same name but the deviations, in my opinion, make the film even more powerful. The sweeping love story is mixed with tragedy, and through the flashback narrative speaks of the power of memory, consciousness, and the place of love in memory and consciousness.

In the Confessions St. Augustine writes about memory and how memory is a repository of love and a defining characteristic of individuality and identity. The ascent to Love, to God, and the peace offered in Love is the essence of the Confessions. The Confessions is the upward ascent of the heart to the wellspring and beating pulsation of Love itself. Why, then, does Augustine shift to discussing about memory in Book X? Augustine’s argument is that we ascend to God by way of memory—and the memory of good things, especially, bring us nearer to God. It is in memory that we have the grandest and fullest ascent to God. Memory, as Augustine explains, contains in it the unconscious and unfallen joy of the love of God that man had in the Garden. Memory is also what defines the self.

When Waterloo Bridge begins the narrator describes the reality that war has descended over Europe once again. The black and white coloring of the film gives it a somber atmosphere which captures the dour spirit of 1939 and 1940. A colonel, Roy Cronin, enters his car to report for his military duties. He is getting ready to report to France. As the car reaches Waterloo Bridge he exits the car. He tells the driver to head to the other side of the bridge and wait for him there; the colonel wishes to walk across the bridge. Halfway across he stops, peers over the night sky, and pulls out a billiken. We hear the voice of a sweet, charming, and innocent young woman and then Roy’s voice in response. The film then cuts to World War I with a younger version of the colonel, then a captain, standing and peering out across the night sky as an air raid siren goes off.

Waterloo Bridge is more than a mere romantic film. It is a film about memory. More specifically, it is a film that touches the unconscious reality of memory and joy which Augustine was describing in the Confessions.

War surrounds the film. The film begins with the declaration of war between Great Britain and Nazi Germany and Roy reporting for duty. The film’s transition to the flashback narrative is also set in wartime and the story is advanced by the frightening prospect of a German bomb raid on London which brings our lead protagonists together in a seemingly random, and chanced, encounter.

Roy meets a troupe of young women, ballerinas, heading to the theatre for their performance when the air raid interferes. As he directs them to the air raid shelter, the purse of one of the ballerina’s falls loose and her belongings fall onto the bridge. Roy rushes over to help her and personally guides her to the shelter. There, the romance between Roy and Myra Lester begins.

Within this narrative is a social commentary on classes. Roy comes from a distinguished Scottish aristocratic family burdened by heritage and social formality. Myra is a working-class girl without a family; the troupe and its crass and crude headmaster, Madame Olga, serve as her surrogate family. Roy is energetic with life, adventurous and sometimes whimsical despite his prestige and heritage. Myra is gentle, shy, and innocent. Roy’s adventurous and energetic spirit brings life to Myra which frees her from her shell and enslavement to Madame Olga. Love, as we witness, knows of no boundaries and certainly of no class boundaries. Love unites.

Yet it is the love story, fixed in the memory of Roy, which moves our hearts. Roy’s 24-hour leave is extended by two days. Roy returns to Myra’s troupe home and the two share another romantic day with each other. Roy even proposes marriage and secures all the rituals and formalities for it—except the church officiation because the law prevents marriage after 3 P.M. Roy and Myra promise to be at the church at 11 A.M. the next morning to tie the knot before his departure to the front.

Bad news suddenly hits when Roy’s leave is cut short. He telephones Myra and tells her he is leaving later that night and wishes her to see him off as he departs. Myra defies Madame Olga and rushes to the train station only to catch a glimpse of Roy as the train departs and they wave to each other. Myra is subsequently dismissed from the troupe, along with her best friend, Kitty, and the two subsequently struggle to live without employment and dwindling revenue. She eventually turns to prostitution to sustain herself and Kitty just as Kitty had been doing to help Myra.

Myra’s hope for marriage and despondent struggle in the aftermath of Roy’s departure and seeming death (incorrectly reported in a newspaper), breaks our heart. The hopeful and lively Myra who so joyously announced she will be married is overcome by the harsh reality of the post-industrial world and the war consuming that world. She becomes a victim of war though she is far from the front. This too, is a great triumph of the film—it shows how civilians, and especially women, are victims of war. The bubbly and energetic Myra awoken by Roy becomes a truly defeated and broken woman. Then, as if by chance—a “miracle,” as Roy says—the two meet again at Waterloo Station when Roy returns home from the war. The promise of a better life reemerges.

However, the return of Roy causes a deep sense of guilt to consume Myra. Roy has been faithful to Myra and his peace in the midst of the maelstrom of war and imprisonment was his memories of Myra. Myra confides to Roy that “I loved you, I’ve never loved anyone else.” Although the guilt that consumes Myra eventually kills her, the love that she and Roy shared is not extinguished as it lives on in Roy’s memory.

Part of the power of Waterloo Station is its portrayal of the Augustinian reality of love and memory. More than 20 years later, with Roy about to embark on another tour of wartime duty, he is comforted by the memory of his love for Myra and Myra’s loving declaration—a truthful declaration—that she loved him and never loved anyone else. The peace that Roy finds on Waterloo Bridge just as the world is being consumed by a new world war is his memory of love for Myra. That memory of love brings a serene stillness in the emerging chaos and darkness.

The flashback story captures a powerful element and reality that the original play, and the first film adaption, cannot capture because they are not works depicting the wellspring of love in the memory of humans. Although the romance between Roy and Myra is over, and it ended in a tragedy, the love which Roy and Myra shared lives forever in Roy’s blessed memory. Roy’s ascent to peace through love is forever with him and guides him—Myra’s loving declaration the still small voice that brings him serenity. In his darkest moments he can always turn to the reality of that joy in his memory.

Love is at once a victim of war but also the one reality of peace in the midst of war. This is what the film so powerfully communicates. Myra’s love, indeed, her innocence, becomes a victim of war. Roy’s love is also a victim of war. But the love that they did share can never be extinguished by war so long as Roy lives.

Roy’s memory holds that original joy he shared with Myra. And that can never be taken away. The unfallen joy of their love lives on eternally in the sacred memory of Roy. Should old acquaintances be forgot and never brought to mind? Waterloo Bridge gives us a very Augustinian answer to that question.