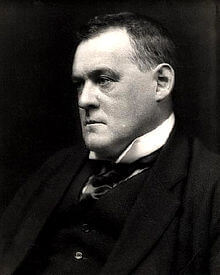

The Problem of Belloc

I wonder why I don’t read more Belloc?

In the ordinary way of things, if one likes this (Agatha Christie, Shakespeare, or cheddar), it would seem reasonable that one would like that (Ngaio Marsh, Ben Jonson, or stilton) which seems so similar.

G.K. Chesterton, whom we read often, worked so long and so closely with Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953), particularly on issues of the Distributionist economic movement, that G.B. Shaw called them Chesterbelloc. They were a sort of intellectual tag-team.

Belloc lived by his pen and he turned out a Missouri River class flow of topical journalism, history, alternative history, poetry, children’s poetry, novels, and social commentary and, as might be expected from one who had to please or diet, it is lively stuff.

There is still a Distributionist movement (very small) and one of his books, The Servile State, is very much alive, as background influence, especially in libertarian circles, comparable to the better known Road to Serfdom.

Another, lesser known work, Characters of the Reformation, is reinterpretation of some well-known historical figures, such as Elizabeth I, a reinterpretation so radical that like Matilda’s lies,

“It made one gasp and stretch one’s eyes.”

And yet, today, while lots of people read Chesterton, and he wields influence sufficient to be seriously annoying to “The Times Literary Supplement” and “The New Yorker,” Belloc, except for his children’s poetry (on which we hope to touch in another segment), is a minority taste.

One patent reason is his reputation for anti-Semitism. Belloc was a polemicist, and judged by current taste, some of his statements are definitely offensive. One can only sigh and concede the point and remind the court, in mitigation, that, when Hitler appeared and when his character became clear, even before the assumption of power by the Nazis, Belloc repented of his former words and denounced the tyrant, which ought to count for something.

But, may we suggest that what makes the difference in the fates of our two authors may be a root political vision.

For Chesterton, everything grew out of the local and the specific. As I mentioned in a previous column, he was the Aristotelian’s Aristotelian. Chesterton was English, and England meant this or that specific place.

Belloc was a naturalized English subject — he was born French, and he seems to have followed a political mythos that might be called “The Lost Empire of Faith,” a vision of Europe united and informed, one might almost say en-souled by Catholicism.

One is particularistic, almost sacramental, the other is universalist. And note what follows therefrom.

The message of the first view, Chesterton’s, says “Reality is right in front of you. Observe, understand, judge and act responsibly. Reality is shot through will the light of heaven. Rejoice.”

The message of the second view is “You are the last knight of the vanished kingdom. You are surrounded by enemies. Smite them! ”

Now of these two views, the first is do-able. The duties are immediate and the rewards just as immediate. The second position puts you at war with almost everyone, and not on general principles but for a specific political goat. One is on permanent crusade.

So Belloc became a polemicist and a powerful one. Wrath flares through everything he writes, like a fire behind a screen. It is very exciting in modest doses, but it won’t do as a steady diet. It wears on one. Moreover, the crusade to which Belloc invites us, his vision of the lost harmony of Europe, a sort of college of Christian Nations with the Pope as Dean, is not now achievable, has not been achievable for a long time and will not be so unless there is a cataclysmic change in the order of things. The world moves on.

So, we read Chesterton all the time.

Belloc, with that one exception, hardly at all.

It is perhaps not a happy outcome. But it is reasonable.