The Soviet Union of 1944–1991 in the Historiography: Representation of a Polyethnic Political Society

The Soviet Union of 1944–1991 in the Historiography: Representation of a Polyethnic Political Society. Nikolay Konstantinov. Ekaterinburg, Grif Press. 2012 252 p. (in Russian).

Note to the author’s translation of the synopsis of the book: I translated with some corrections the fragments from the book to present the analyzed in the book issues. Notes and references were mostly omitted; in a few cases, when they are kept, they are in the square brackets. Also I added numbers of pages in the book in the parentheses after each fragment.

Introduction

Recognizing of the fact of human diversity is basic for the anthropology in all its variations, that originated as a science to the end of the 19th century. But the banality of the statement is in contrast with the actuality, that despite the triviality of the idea of diversity of humanity, and that it is desirable to take this fact into account both in human sciences and in social institutions, the idea have accepted very slowly. The 20th century was spent on comprehending the significance of the fact of human diversity as a significant element of social life. (p. 4)

In human sciences have been acquired a much experience of academic description, analysis and representation of polyethnic societies up to the 21st century. The landmark in the systematic study of polyethnic societies was publication, from the end of the 1930s, by a British anthropologist John Furnivall his works on the Southeast Asia, that became one of the testing areas for analysis of ethnic heterogeneous societies in contemporary science [Furnivall, J.S. Netherlands India: a study of plural economy. Cambridge,1939]. In his works Furnivall suggested the concept “plural society” for description of situations when a few societies with different ways of life, united by the supreme power in one polity, coexist together without common political culture. That is why the only site for interactions among them is a market as a place for exchanges. As an example of such type societies Furnivall provided an example of the European colonies. In a situation of absence of civic communication between the individuals both logic of market and right of force overpower logic of mutual aid. The sequence of such plurality of society was its disorganization. Later, the concept “plural society” have been lost its original connection with social and economic issues, and it was applied for description of multicultural societies, cultural heterogeneity [for example: Lijphard, A. Democracy in plural societies: a comparative exploration. New Haven, 1977] (6-7)

In the 1960-1980th, in addition to new polyethnic countries of Africa and Asia, the countries of North America and Western Europe had got into the focus of the analytics, who regarded them as cultural and ethnic heterogeneous. (7-8)

The 1990-2000s were the time of recognizing and growing awareness of the fact that cultural complexity of political societies is normal state, not anomaly. The bloody ethnic conflicts in the ex-Yugoslavia, Post-Soviet states, study of experience of post-colonial Tropical Africa were demonstration of the fact that creation of new national states is not the only proper mean for avoiding bloody interethnic conflicts. (8)

In the USSR due to the fact of its scale and role in planetary historical processes, the vanguard of which it used to be represented officially and recognized by the observers, many of the listed problems were actual, recognized and solved, although in the other ways, than in the other countries. For example, the problem of status of the representatives of other races was less actual for the Soviet sociologists than for the American thinkers. Due to lack of overseas territories and of officially accepted colonies the options for transformation of ex-Russian empire into the Soviet Union were different than, for example, in case of transformation of French colonial empire into the French Union . . . The problem of typology of the USSR as an anthropological phenomenon by the limited conceptual means is not unique. The same difficulties had and have political thinkers and observers of processes in such polities, for example, as British Empire of the first half of the 20th century, European Union, and in recognized as the national states – Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States of America. (9)

In the title of the book the Soviet Union is designated as a political society. This characterization may be considered as one of possible appearances of such multidimensional phenomenon as was the USSR. But it is significant, because in the USSR ethnicity was closely connected with collective life. Political society is not only a fact of the external world that may be investigated by an external observer as a natural phenomenon, as a social system, for example. For its members the society is the environment for their activity, consciously constructing and sustaining. Perception of society as the wholeness cannot find a basis in ordinary experience, in case if its boundaries beyond the horizon of individual experience. An image of human community as a phenomenon that is independent from its members, who construct it, is an outcome of description of a structure, created in the course of their interactions by means of inherited and elaborated symbols. Self-description of a society’s structure and interpretation of symbols are concurrent with process of constructing and reconstructing of human organization by presenting the latter as an object of consciousness and intentional activity. An existing community is, first of all, a component of internal life of its bearers and only than an observable fact of external world. [Note 11: Veogelin, E. The New Science of Politics. Chicago, 1987; the concept “political society” had been already applied to the Soviet Union . . . About a political society as an outcome of co-constructing activity of its members as an intersubjective phenomenon see: Habermas, Jurgen. Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action] (11-12)

Self-description of community is a significant condition for its sustaining and development. In the USSR self-description was an objective of the social scientists. External description of community is mirroring its perception from the point of view of other experience. External description of the USSR was an object of the Sovietologists. When community is ceased to exist, it is described historically, in the perspectives of political communities that replaced it. An image of a society is constructed on the ground both of articulated knowledge about human and collective life, and elaborated for representation of society symbols. In the course of intellectual communication this symbols may be transferred in a new environment and get a new meaning, as it was with such concepts (and, simultaneously, symbols) as “nation,” “nationality,” “empire.” (12)

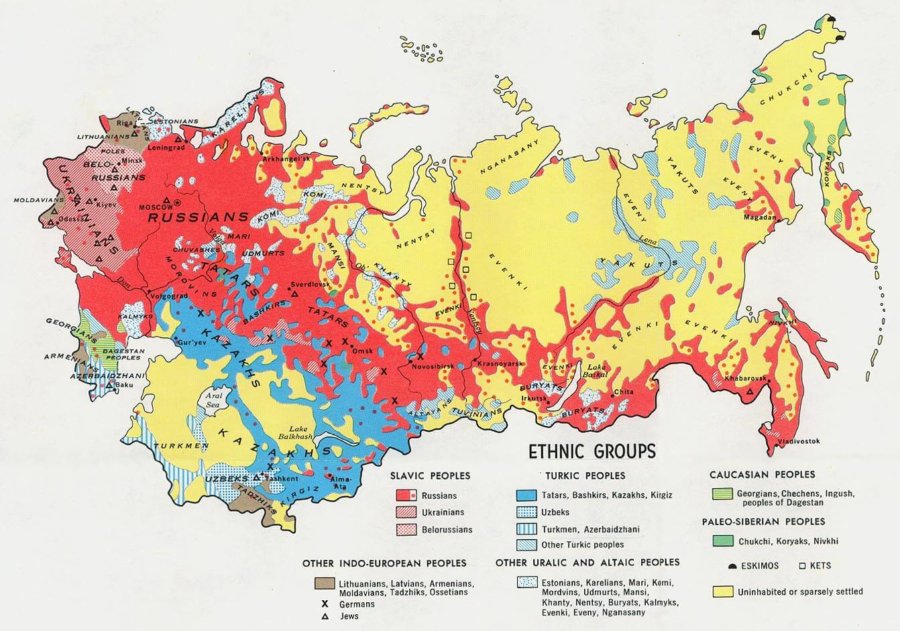

The USSR is regarding in the book as a polyethnic phenomenon, that is why the category of ethnicity is pivotal and it is taken as merely as a fact, as an element of academic practice. (13)

Ethnic heterogeneity of the USSR as a historical and anthropological phenomenon was not subject for investigation of a historian of knowledge despite the fact of existence of huge amount of primary material for analysis. (17)

Essay I. Issues and Categories for the Studying of Polyethnicity of the Soviet Union of 1944-1991

May be assumed, that, although. the prognosis about the “Islamic treat” was not validated directly, implicitly, by mediation of the analytic’s works, including foreign, as a possibility, it had been taken into account by the Soviet establishment during selection mode of reorganizing of the collapsing USSR. (73)

Essay II. Typology of the Polyethnic Soviet Political Society

In the historiographical picture of the USSR, constructed by the soviet historians, had been presented three types of subjects of historical and political process: collective social, collective political, personal. The subject of the first type was “people,” “peoples masses”: since the Soviet Union had been represented as the first country in the world where not hereditary aristocracy or natural aristocracy but the ordinary persons, earlier had been oppressed by the formers, had become the creators of history. The subject of the second type was the “party” – CPSU, that defined as a mean for organization of masses for the governed transition to the future communist society, where the logic of history of the ages of class formations would be exhausted; as the organization that was created by the revolutionaries who have comprehended the logic of history and sustained by their successors. In future the difference between this two types of subjects would be eliminated, because comprehension of the laws of history by every individual would be of such extent that organized separation of those who know would be needless, as any guiding by force or surveillance.

That is why status of the subject of the second type was ambiguous. From the one side its existence as the separated should be limited in time, from the other side, this subject articulated and realized the program of constructing communism by incorporating and mobilizing different groups of multimillion population for reaching the set goals. But the human mass is heterogeneous, there are many differences in it: language, confessional, class, race. In the age of rapid development of technologies and related to them radical changes in a material component of ordinary life and propagation of egalitarian mindset, choice of language by the bolsheviks from the list of traits was logical. Language is not only a mean for communication between the individuals, it is mean to appeal to masses, especially to illiterate, mean for feedback with them, a mode to spread the ideals of egalitarianism and democracy by incorporating in power not only educated polyglots but ordinary persons, speaking only native languages. That is why development according the principle of power of people meant development not of the abstract mass, but diverse population of the Soviet Union, that was designated as “the peoples of the USSR.” Each of them was regarded as a subject of the historical process in the boundaries of the USSR with the status of socialist nation or, in case of small number, of socialist people, with their own national state . . . (81-82)

Regional cultures were considered as the means for rising of level of education of the mass to the necessary, that is why it was presumed that language and culture no more than the means of indoctrination with the universal truth of the Marxism-Leninism . . . Communist society of the future should be planetary or, for the beginning, continental, that is why there should be common language for participation in building and sustaining of the communist society on the supranational scale. (83)

. . . one of core propositions in the soviet model of “socialist multinational state” was the statement of its qualitative difference from all other types of polyethnic polities. In the soviet social science of the 1940-1950s the polyethnic states designated as the multinational states. In the 1960s Solomon Bruk suggested to classify them as the “ethnopolitical formations” . . . Modern age European empires as Austro-Hungry, Osman Empire, contemporary polyethnic states as Third Reich Germany, British Empire, France, and USA were characterized as “bourgeois multinational states”. . . Simultaneously the soviet social scientists considered the USSR in historical succession of the polyethnic polities of past with the pretension to universalism beginning from the empire of Alexander of Macedon and Roman Empire. The difference of the USSR from the pre-Modern and Modern polyethnic universal polities was seen in the uniting principles. Soviet social scientists considered that the political unity of the non-socialist polities was grounded on coercion and compulsion, while in the USSR it was founded on free will. (84-85)

The principle of friendship of peoples was connected to the principle of internationalism. The idea of internationalism was meant that class, horizontal solidarity is more advanced than national, vertical solidarity. Class solidarity was defined as struggle of the oppressed, that are united around proletariat, with the exploiters. Assumed, that during this struggle and after liquidation of exploitation would be created rational communist culture, that is grounded on technology… The idea of friendship of peoples was an interpretation of the principle of internationalism on a language comprehensible for an ordinary inhabitant of the USSR. (86)

The idea of friendship of peoples was grounded on the assumption that main subjects of history are groups, collectives, in this case are peoples, not individuals, who were viewed as the epiphenomenons of nation (or group) and acquired the qualities of subject only due to extent of connection, identification with a group. That is why in the 1940-1950s the Soviet social scientists paid main attention to study of relations among the Soviet republics [that they regarded as national states]. When in the 1960s the Soviet researchers-ethnosociologists had begun to study the “interpersonal national relations” they expressed doubts that the investigation of the former issues is justified. (87)

There were two main interpretations of connections between polyethnicity (“multinationality”) and territoriality in the Soviet social science of the 1940-1980s. The focal point for the discussion was the proposition that in future the nations would merge, integrate into the united communist humanity. At the center of the discussion were the problems of the speed and the stages of this process. (88)

There were two modes of official representation of the USSR as the polyethnic polity: the official and the semiofficial, and in the latter had been reflected organization of the power, not of the federation. (101)

Up to the end of the 1950s have been arisen again the problem of articulation and legitimation of further steps for integration of heterogeneous population of the USSR in coherent unity. As the sequence was announce of the conception of the “Soviet people” at the 22 CPSU congress in the 1961, that has been argued after the 24 CPSU congress in the 1971, and thus became the significant component of self-description of the Soviet political society . . . Earlier, the concept of the “Soviet people” used to be a metaphor in the official rhetoric for description of unity of the population of the Soviet Union . . .

The reference point for solving the problem of self-description was the Stalin’s definition of nation as the unity of territory, economy, language and culture. According to the image, social integration of the Soviet space and formation of the common economy had been accomplished, only the spheres of language and culture had been viewed as should be integrated. The idea of the composite nationalism or the hierarchy of subject nationalisms that was expressed by Nikolay Trubetzkoy, was too unusual to the Soviet view of the concept of nation. That is why one nationalism should exclude the other. That is why the suggestion to use the term “nation” for the description of the Soviet polyethnic society, and not only for the designating of the constructed on the base of ethnic groups socialist nations, was perceived so ambiguously, that it was not accepted. Instead was accepted the idea that “in the USSR has formed the new historical community – the Soviet people.” (116-117)

As the result of lack of consensus in the ruling class the word “people” was chosen instead of the concept of “nation.” The word “people” in the vocabulary of the Soviet social knowledge was much more a political symbol than an articulated concept. And this was its advancement, since it was easier to use it for articulation a new concept and symbol for description of the Soviet political society. The word “people” in the Soviet vocabulary used to be connected with the collective subjects and, especially, with the phenomenon of mass. The Soviet political society was represented as the first in the history society in which the masses had become the conscious creators of history . . . In the 1955 the Soviet historian Anatoliy P. Butenko had written that “the people is historically transforming community of persons, consisted from such parts of the population, who by their objective state can commonly participate in the solving of the tasks of progressive, revolutionary development of the country in the concrete historical period.” At the end of the 1960s P.M. Rogachev and Matvey A. Sverdlin have noted that “in the conditions . . . of the socialism “people” is always wider than “nation” because the former include all the builders of the communism of all the nationalities on the territory.” Thus was suggested the difference between the view of “nation” as extraterritorial, ethnic, extra phenomenon or “ethnos,” and the image of “people” as territorial community. (120-121)

The conception of the Soviet people as a communal territorial non-national community was articulated and as its subject had been viewed individual or, precisely, individuals in their multitude. For example, the Soviet historian Maksim Kim had characterized the Soviet people as “the first in history free union of free workers, the first socialist collectivity of persons.” This articulation [with attention to an individual] had been connected with the preserved tradition in the Soviet social knowledge of the view of ethnicity as a phenomenon of the pre-industrial age. An industrial and urbanized communist community was imagined as founded on solidarity of its members, on the principle of internationalism… From the other side, the view of the internationalism as the union of individuals united by common interests and collective fate was complemented by its view as the unity of socialist nations. (121-122)

During the discussions of the Perestroika age the disputants have discovered that the country’s cultural and social diversity was much greater than they thought before. The state of “homogeneity,” the reaching of which had been viewed as one of main achievements of the Soviet history, had been regarded in the new situation as the “obstacle on the way of development” and as the “administrative myth.” (127-128)

The other way of solving of the problem of classifying of the Soviet Union was related with the emerging of the new states in Africa and Asia in the course of decolonization, that was fostered by the Soviet foreign actions… (128) The resemblance of the USSR with the countries of the South Asia was noticed . . . (131)

The new perspectives on solving of the problem of typology were discovered by comparison of the Soviet Union with the United States. In the mid of the 1960s Zbignev Brzezinski and Samuel Huntington have noticed, that the USA and the USSR were the first significant countries in the world, that represented themselves as the pure political unities. The reference to geography in the name of the USA is symbolical because to be the American, as to be the Soviet, means to resemble the ideal. Citizenship in this cases is much more than only loyalty to the national community . . . The writer and social thinker Alexander Zinoviev had noticed resemblance of the structures of the USA and the USSR. He noticed, that in the USSR the comprehending of the difference between its structure and the structure of the national states was the foundation of the Soviet policy for creation of supranational society in contrast with the USA, that continued to self-describe itself as the national community. Alexander Fursov has noticed, that “the Soviet Union was an attempt to construct principally new than imperial or nation-state type of polity, principally new type of social and economy community – supranational, proto-global (the “Soviet people”). It resembles to the American nation that is “in the project is proto-global community too, although of the other type than the ‘Soviet people.'” (132)

In cases when in the focus of attention was not the community of citizens, society but the state, territorial dimension, the USA and the USSR are compared as the states-continents, states-worlds. Petr Bizzilli was one of the first in historiography who has paid his attention on the differences in the internal structures between the Russia/USSR and the USA, from the one side, and the European nation-states, from the other side. He underlined, that nation is the phenomenon of the European history and its widespread is limited by the boundaries of Europe. Hy has noticed that the USA and the USSR were the states-continents type, whether they would be described as the nations. And that is why new approaches for their description, other than the conventional, are desirable. European political thinkers Hannah Arendt and Raymond Aron noticed the principal differences between the USA and European national states too. In the Soviet social/political science the USA and the USSR much more had been opposed one to the other, then had been compared. Although the Soviet sociologists used to define the American political society not as a nation but as a meta-ethnic community [or identity]. The main difference between the states-continents and the European national states is considered to be grounded on less differentiated substrate in the latter . . . In the states-continents the substrate is very complex and include multitude of the elements with the diverse trajectories of historical development each of which could be considered as the analogue of the classical European nation; that is why a goal is creation of a supranational community. The American historian Frederick Turner had written on this occasion, that since the USA are comparable with whole Europe “it must be thought of in continental, and not merely in national terms. Our sections constitute the American analogue of European nations.” (132-133)

The concept “Soviet people” officially used to represent one of two dimensions of the Soviet political society – community of citizens. The second dimension is state – officially represented as multinational. (133)

The Soviet Union was viewed [in the Soviet social science] as a direct outcome of the social engineering, creating the rationally organized society. (136)

In case of approaching the project of constructing of the Soviet people in comparative perspective may be find at least one analogue, with all the differences among them: it is the idea of “constitutional patriotism,” had been expressed by the German political philosopher Dolf Sternberger in the 1979 and developed by Jurgen Habermas. The common trait of both ideas, although by different reasons, is the endeavor to transcend national identity and particular ethnic identities. In case of the USSR it was intention to overcome the boundaries of ethnic diversity. In case of Habermas the aim was to elaborate the principle that could be common ground for loyalty of citizens to a state, in his case to Germany, both from the side of immigrants and Germans, without reviving nationalist ideas, that were a cause for the Second World war and genocides of some European peoples, including Jews. (143-144)

. . . “communism was degenerating into empire because it was the only ready form” [Petr Vail] for perception of the changes in the USSR, that had been elaborated both in the emigration and Sovietology up to the mid of the 20th century. (160)

The concept “Soviet system” was an element of self-description of the Soviet political society. It had been implemented in the period, when the Systems approach was only in the state of formation, but had been recognized, that the new age of history had begun. (174)

The Soviet ethnologists in the 1960s-1970s made an attempt to elaborate an alternative system of categories for description of polyethnic political societies for, firstly, distancing from historically articulated types of self-description, that regarded as dangerous political symbols (especially “empire”); secondly, for classifying of diverse variations of polyethnic communities. But this categories didn’t spread out of the boundaries of Soviet ethnology (179)

Up to the beginning of the second decade of the 21st century the triad of classical types [nation, multinational state, empire] was supplemented by multiple intermediate types and alternatives to them (as ethnopolitical community, for example). Nonetheless analytics are in the situation of circle, transition from applying of one type to the other type . . . The example may be constructing of typology of polyethnic polities on the national states and the states-nations by Juan Linz snd Alfred Stepan [Linz, J., Stepan, A.C. Crafting state-nations: India and other multinational democracies. Baltimore, 2011], that is an analogy of the classification on the national states and the states of nationalities that had been suggested by Karl Kautsky and Karl Renner (Rudolf Springer). The other example may by rising of interest to the multinational polity type but in the corrected form as a multination [Kymlika, W. Multicultural citizenship within multinations // Ethnicities. 2011. Vol.11. No.3. P. 281-302] (179-180)

There are may be imagined at least two ways to come out from this vicious circle. The first one, as in case of the Soviet Union, it may be an articulation of alternative concepts. But, as may be concluded from the Soviet ethnology experience, this way may be rejected by academic community. The second one is critique of key categories of analysis and the “nation” first of all . . . Someone may follow the suggestion by Valery Tishkov “to forget the nation,” that is a reaction on ambiguity of this category. (180-181)

For the phenomenon, that Hans Kohn designated as “civic nations,” common past is secondary to common future and common everyday activity as the means of binding of members of political society . . . By studying of the particular pictures of the past researchers investigate actually the ethnic phenomenons even in cases, when they designate them either as the “nation” or by the other concepts, for example, the “people.” As the result, the category “nation” actually is designation for an ethnic group that holds its own sovereign state or seeks to get it. [Note 486: The other question what are the reason for this practice that is not bounded by the studies of the societies of Post-Soviet Eurasia. May be it is one of the forms of expression of the crisis of democracy of the edge of the 20th and 21st centuries in the academic discourse, and originating and wide-spreading the phenomenon that is designated as “post-democracy”, one of the indicators of which is weakening of the significance of images of the future as the factor of binding of members of political societies] (182)

Essay III. Aspect change in the studying of the USSR polyethnicity

[Nikolay Girenko considered that] one of the traits of any society is diversity of levels of development of its subsystems. In case of the USSR it appeared in the difference of its subsystems, both regional and functional, by extent of their rationality and openness, their capability to coordination, that is minimal in “closed,” rigid societies. In the USSR such “closed”, non-adaptive subsystems were the societies of Caucasus and Central Asia, and the subsystem of government. (194)Benedict Anderson as Clifford Geertz and Nikolay Cheboksarov had specialized on study of the new societies of South-East Asia, including Indonesia, that have become the testing area for study of polyethnic societies in humanities of the 20th century . . . Because of confessional, cultural, language diversity, endeavor to construct the common identity, the USSR by its structure more resembled originated in the course of decolonization the new states of Africa and Asia, than the classical national states of Western Europe, that was noticed by some observers. (195-196)

Mikhail Gefter recognized ontological primacy of individual differences over any collective unities. It means primacy of diversity, as non-reducibility of differences, against variety, as derivation of differences from the common observable origin. Ignorance of this fact, as a fundamental condition of human existence, even with good intentions, may be a cause of violence . . . That is why Gefter noticed that “insisting on the one correctness leads to such outcome that instead of universal humanity we will get universal death by mutual rejection and for that we will not even need nuclear explosion” (198-199)

Societies of different stages of development hardly reconcilable one with the other. That is why a new model of development should be constructed on the premise of necessity for simultaneous and sometimes common coexistence of societies of different types. The common norm of economics can’t be a robust foundation for such complex society . . . Neither could be law . . . Neither could be ideology, since it nothing more than an ideal model of interactions. And when it is implemented compulsory even with best intentions, as it was in case of the USSR, it will be condemned as containing in itself a seed of unification. That is why a new cohesion of humans may be grounded only on the ethical interactions between them and only then will follow ethical interactions between their assembles. In mind this shift may be appeared as transition from historical thinking to evolutionary as once had been transition from mythopoetic to historical thinking. (205-206)

By taking as the object of analysis by Geertz, Gefter, Girenko not collectivities, as ethnic groups or states, but individuals emerged new means for describing the USSR and its experience in new perspective, that may be designated as anthropological. In its foundation there are academic, practical and intuitive knowledge about human behavior, modes of identification, changeability optimum: modes of interactions, modes of communication and transfer of information in space and time. In this direction it is possible to allocate the elementary units, forms of culture, that may be considered as the ‘genotype’ of collective life, by which is determined its architectonics in all its multidimensionality. (208)

Current approaches to description of polyethnic societies may be distinguished on classical and non-classical. Classical approaches framework is focused upon collectives, groups such as nations, nationalities, ethnos, as in case of the USSR, that are considered as initial to individual structures, that may be categorized by objective, external features (as physiognomic, language, behavior, material culture) regardless position of an individual. Collective phenomenons are considered as the bodies that may unite with other, engulf them or disunite. Consisted from this structures polity is designated as polyethnic. According to mode of relations between its components, it is categorized by one of the common types: national state, multinational state, empire . . . An alternative to classical approaches are non-classical. In the framework of the latter at the focus of a researcher is an individual and, first of all, her consciousness and psyche. Collectivities are regarded as an outcome of interpersonal interactions and function of mind. Phenomenons of collective life as ethnicity, for example, are viewed as unstable and flowing. Social complexity considered not as an exclusion, but as a norm. That is why traditional typology is hardly applicable to such societies. Classical typology is applied more by inertia.

For example, Clifford Geertz, Mikhail Gefter, Nikolay Girenko sometimes used to define the USSR as an empire, although by context of their statements it is comprehensible, that it is much more an image, and applying is the sequence of necessity to classify the phenomenon in some way [Note 530: the good example may be using the category “empire” for designating of the European Union. After the reservations of the uniqueness and incomparability of the EU with polities of the past the EU is classified as an “empire”, although with the adjective for underlining its principal differences from the past empires: as “non-imperial empire” by the president of European commission Jose Manuel Barroso in 2007, or as “post-imperial empire” and “cosmopolitan empire” by Ulrich Beck and Edgar Grande] (209-210)

This shift of attention from the collectives, groups to mind and behavior of individuals as factors of evolvement of societies may be designated as aspect change in study of complex anthropological phenomenons. (210)

In the aftermath of the aspect change new issues in study of complex societies were set. In the framework of classical approaches the subjects of investigation are structures, external to an individuals, and their interactions. Such issues are studied as interethnic relations; ethnic and national processes (as consolidation, acculturation, assimilation, divergence of groups); national history; modernization. (211)

essay IV. Ethnocultural complexity of Soviet Eurasia, the Mid-1940s-1991: Modes of Representation

The first mode of description is the elimination of ethnocultural complexity, which is considered as transient, ceasing phenomenon . . . The example of such approach may by idea of “melting plot”, through prism of which the Soviet actuality used to be percept by the first American Sovietologists. (218-219)

The second mode of analysis is the fixation of ethnic and cultural groups boundaries, that are considered as immutable. History, in this case, is interpreted as the process of interactions of such groups categorized by the interpreter in the boundaries of the country . . . Individual is regarded as not an autonomous phenomenon but as an element and epiphenomenon of a group. That is why is unimaginable changing and shifting of the boundaries as the outcome of interactions of individuals . . . Subject of historical process in this case is an ethnic group acting in the boundaries of a native (“ethnic”) territory with the outcome in an ethnic (in Soviet vocabulary – “national”) state of this group. (221)

. . . [the idea of a] egalitarian territorial (republican) community (that designated as a “laborers of republic”) in which all the members of all nationalities would be in equal condition was hardly consistent with the preference to the status of one group [“title”]. The only alternative was the mode of elimination of cultural complexity. That is why [the Soviet] analytics oscillated between the Scylla of ethnocentrism and Charybdis of integrationism when the underlining both of them simultaneously was obligatory. (223)

In the framework of the third mode of analysis as the unit of analysis is token a social territorial community of individuals, who live at the territory irrespectively of their ethnicity, culture, confession, that are regarded as secondary . . . The key categories in this case are citizen and political . . . First attempts to represent the postwar Soviet society in this way belong to the 1960s when a few investigators proposed the statement that the nationality factor diminished in the course of the constructing of communism and crystallize in the conception of the “Soviet people.” (225)

Civic-political model may be characterized as inclusive, that is permanent expanding of a community’s boundaries by the inclusion of new groups and individuals, who are considered as “others,” not “aliens.” (227)

The first three modes have applied to description of the USSR from the beginning of the period but applying of the fourth mode is a new trend. In the framework of the fourth mode is the recognized cultural and ethnic complexity and differences as the value in itself. History regarded as the process of permanent restructuring of groups and shifting boundaries between them, creating of new and ceasing of previous in the course of interactions of individuals. Countries are regarded not as a homogeneous wholeness but as “conglomerate of differences, deep, radical and resistant to summary” [Geertz, C. Available Light: Anthropological Reflections on Philosophical Topics.2000. P. 224] . . . Thus, an individual is regarded as a subject of history. (227-228)

Conclusion

Community is, first of all, an element of internal life of its members and only than is observable element of the world. With ceasing of the image of the society and its replacement by the image of the other society the former as the fact of external world supersedes from the sphere of interactions and transforms into an object of reminiscence and continue its existence for some time in form of shatters of the former. (234)

Both the Soviet government and the Soviet academic environment were not autonomous neither from the opinions of their compatriots, nor from the world of intellectuals on the other side of the “iron curtain,” whose attention was closely focused to the Soviet Union. Foreign researcher suggested their interpretations of the processes in the USSR, especially, of the Soviet model of development of Central Asia region and its typology . . . By joining of the Soviet social scientists to discussion with their opponents even by objections, ideas of the latter had become factor that influenced on the academic (and non-academic) self-description of the Soviet political society. In cases when this ideas had been regarded as suitable, as in case with the idea of A. Toynbee that the USSR was the model of the world, they had become an element of self-description and representation of the Soviet Union. (234-235)

Although many of aspects of the process of articulation of the Soviet political society is not clarified yet, one may say that there were a lot of participants of this process: the government, the Soviet scholars, foreign Sovietologists, dissidents-publicists and, after all, everyman. In this meaning someone may talk about the USSR, the Soviet political society, by applying the concept suggested by Jurgen Habermas, as an inter-subjective phenomenon, as the outcome of collective co-construction and interactions of those, the object of whose consciousness was the USSR. And each of them, whether consciously or not, have contributed more or less to the process of its existence. Participation of foreign observers in such intersubjective communication is normal. (235-236)