The Universal Search for Human Dignity

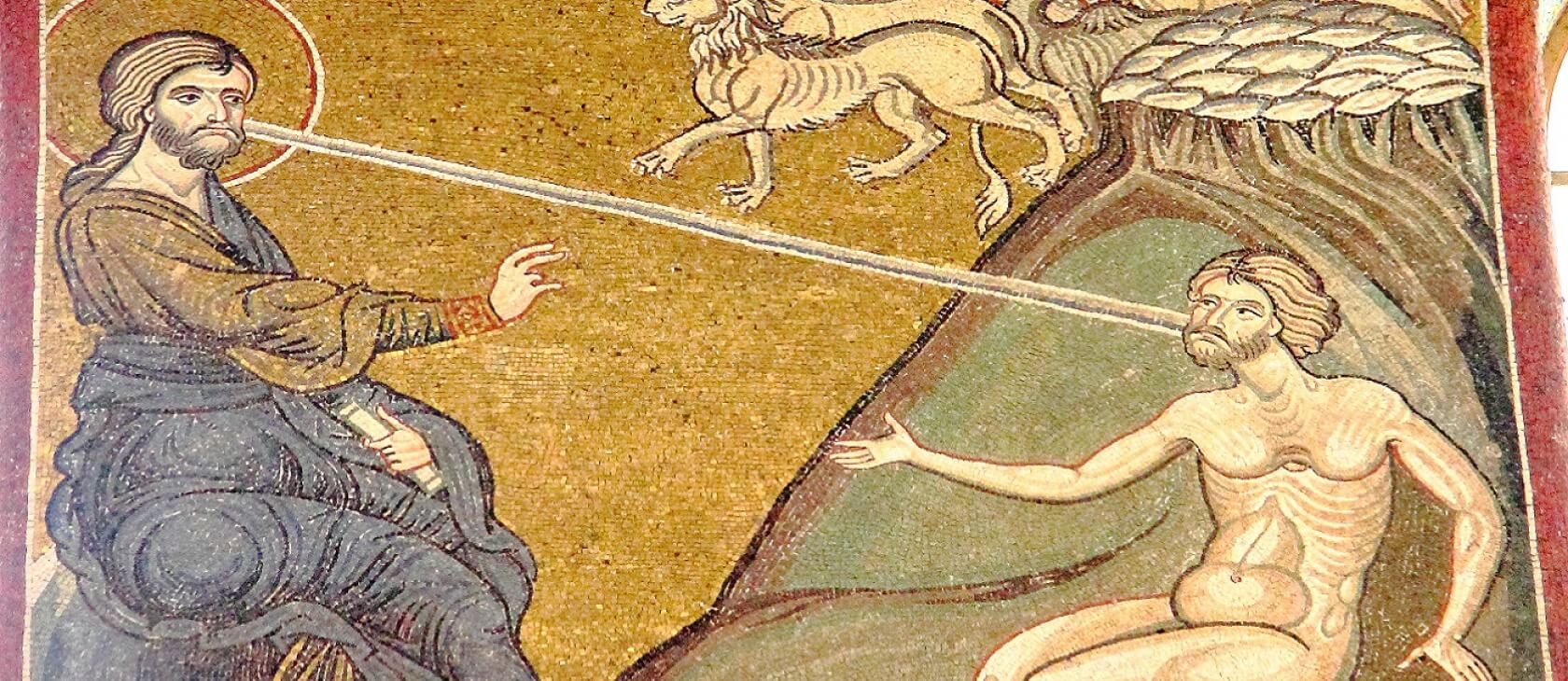

Most people, understandably, have not reflected systematically on the idea of their own inherent dignity: what exactly it consists of, and why it is “inalienable.” Even fewer have taken the trouble to consider why this particular “worth” makes all human beings equal to each other. And fewer still have concerned themselves with the fact that a truth of equal, inherent personal dignity presumes human participation in transcendent value.

On the other hand, since a basic awareness of personal value is intrinsic to humans as self-conscious, every mature person has a desire to live in a way that resonates with that awareness—and thus has developed some ideas about what achieving a dignified existence involves (while they recognize too, of course, that people develop wildly varying notions on the matter). Individuals are motivated and drawn forward by these ideas—ideas resting on multiple sets of images tied to very strong feelings—because every person seeks not only to feel that their existence is meaningful (as Viktor Frankl has explained so well), but also seeks to feel their living is dignified.

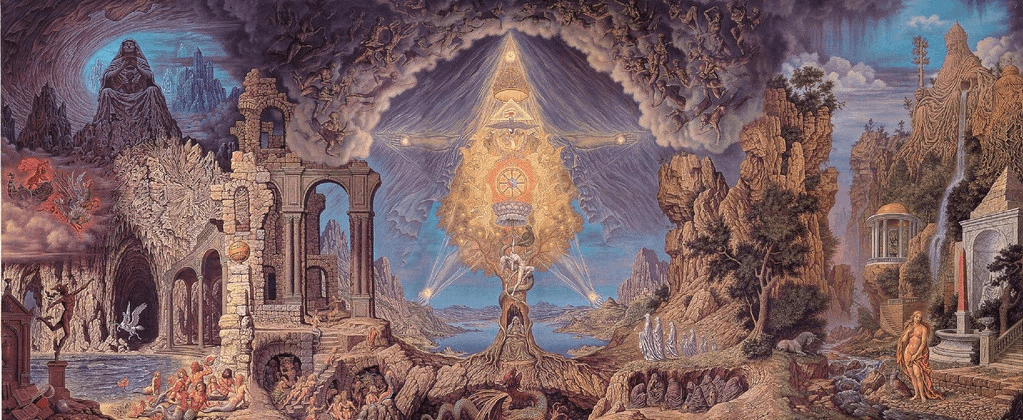

Any sufficiently rich account of human existence indicates that the pursuits that can dominate the pattern of a life—for example, a striving for the greatest amount of pleasure (see Kierkegaard’s portrayals of “aesthetic existence”); or the longing for security above all things; or the struggle to attain wealth and power (portrayed so often in films and novels, not to mention the daily newspaper); or a hunger for knowledge in matters practical or speculative; or efforts to achieve a life of virtue as exemplified by historical and cultural heroes (or family members)—all serve the purpose not just of filling one’s consciousness with a sense of meaningfulness but also of estimableness.

This is because we all sense, as Eric Voegelin points out, that human existence is “participation in a movement with a direction to be found or missed,” and no one in fact wants to miss the path of meaning and value: no one wants to feel pointless.

Lonergan makes the same point by saying that our overriding concern in life is a “dramatic” concern: we desire to turn in a meaningful performance that is admirable (and even at its best beautiful), but at the very least a performance that doesn’t seem, to ourselves or others, completely ridiculous and hollow.

Now, our performances in life are a matter of putting our freedom into play. We cherish our freedom; we glory in it; and we use it to make our lives feel purposeful and estimable, that is to say, dignified. This shaping of our lives is a kind of artistry, since art is, most broadly speaking, an exploration of the possible uses of freedom—in this case, of the possibilities of what a concrete human existence (myself, this “I”) can be. Hegel described Shakespeare’s greatest characters as being “free artists of themselves,” and this is what we all are, to some degree. The search to achieve a dignified existence is a search for artistically manifested dignity in the performance of living.

If one asserts, as Lonergan does, that this search for dignity is a universal human characteristic, the response may be one of skepticism. There appear to be two principal objections.

First, it is pointed out that many people engage in “lifestyles” and pursue goals that can hardly be described as dignified in any typical sense of the word. The appropriate answer to this is that every person identifies “the good” with spontaneous or habitual objects of desire; these objects of desire are imagined in terms of successions of varied “acquisitions and attainments” (in Lonergan’s phrase); and the acquisitions and attainments that persons actually associate with meaningful and dignified living can reflect imagination that is immature; damagingly limited by circumstance and situation; benighted; perverse; shot through with resentments (conscious and unconscious); or riddled with biases.

In other words, there are—to judge in comparison with the achieved dignity of the most virtuous persons (Aristotle called them spoudaioi, “morally serious” persons)—a large variety of mistaken or shallow notions of dignified living whose imagery effectively inspire human performance.

In present-day culture, consumerist greed, vanity-prodded hedonism, and a fascination with and longing to “touch” celebrity are a few of the drives absorbed and adopted as the stuff that makes life charmed and worth living. In considering the universality of the search for dignity, then, we need to recognize that here again “dignity,” or “dignified living,” functions as a heuristic notion. “Dignity” in this context can be heuristically defined as: “that which a person aims to artistically manifest through free performative choices.”

There is a second, more radical objection to affirming the universality of the search for dignified living. This objection directs attention to the not-infrequent human indulgence in, and enjoyment of, self-debasement and self-degradation. People can, and some do, take satisfaction in humiliating their own thirst for esteem, in ridiculing and lacerating their own longing for truth and goodness, in reviling and attacking their own sense of worth. To recognize how even this can be understood to be a perverse form of the search for dignified living requires a bit of dialectical subtlety—and, of course, a sense of irony. Not surprisingly, perhaps, we find a helpful clue provided by that master dialectician and ironist, Friedrich Nietzsche.

One of the epigrams in Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil states: “Whoever despises himself still respects himself as one who despises.”

The existential irony of this insight is transposable to our topic as follows: “Whoever degrades himself still respects himself as one who degrades.” And it is not difficult to identify in what this essential self consists, the self who is still respected as the one choosing its own degradation. It is the self as freedom.

We can indulge, even revel, in the creative freedom we have to attack and debase our own dignity. Sometimes this is done to outrage our sense of dignity because we feel that our idea of it—the sets of images spontaneously called to mind by the idea of “worthy” behavior and “valuable” living—has been imposed on us, and so we associate living up to it with hypocrisy, or with oppression, or with failure. (Adolescent rejection of parental examples of dignified living, by way of “self-harmful” behavior, is an everyday example. Think, too, of those situations, in any period of history, where cultural ideals of “achieved dignity” that are foreign to those of a native culture, and as a practical matter unlivable by them, have been forced on native communities: a free rejection of one’s sense of personal value is an understandable reaction, even if not a predominant one.)

And sometimes, self-degradation is engaged in to outrage the sacred source of human dignity, out of indignation at the dependence of our freedom on transcendence—on the mysteriously free ground of being which has given our freedom to us.

For our freedom really is freedom, although we did not grant it to ourselves: it is our independence. And it can be felt that the only sure way, the only really convincing way, of proving to myself that I really am free is to reject not just the socially-expected but, more profoundly, the transcendently-intended goodness and meaningfulness that obliges my freedom. (Dostoevsky has explored this topic with typical thoroughness; the character of Kirillov, in The Demons [aka The Possessed] carries this rejection as far as it can go.) At the limit we find the Sadean persuasion, which derives from the insistence that I can only have real worth if I resist my life in “the Good” as this is grounded transcendently. (Those who intentionally set out to damage or destroy the life stories of those who are innocent, virtuous, or simply striving to be good—a theme examined brilliantly by Abigail Rosenthal—is another way of rebelling against the transcendent value to which humans are existentially obliged for their freedom and for moral standards, Kant’s “categorical imperative” among them, to be found in conscience.)

But all this, too, is patently an effort to achieve a sufficiently free, sufficiently self-constitutive performance in life.

Self-degradation is no exception to the search for dignified living.