The Uses of Plato in Voegelin’s Philosophy

Exegesis vs. Interpretation

While it may be that God is the measure of human beings, Plato is certainly the measure of anything written about God, human beings, and their relation. So much so that when one studies and writes about Plato, one unavoidably reveals more about oneself than about Plato.

A platitude, perhaps. Nonetheless, I believe it to be true of Eric Voegelin’s work–the later writings as well as the earlier ones. This is not to suggest that we do not learn anything about Plato from reading Voegelin: we do. But it is very much Voegelin’s Plato we encounter throughout. And that is my topic: not Plato per se, but rather how Voegelin uses Plato in his own work, and more specifically, in his philosophy of consciousness.

Plato is always central to Voegelin’s philosophy: but it is a highly selective Plato–often no more than a few favorite passages within a rather extensive collage of references to the various things that were important to Voegelin at one time or another. The task I have set myself is to explore what may be learned about Voegelin’s philosophy of consciousness by examining his unique reading of Plato.

On occasion, Voegelin presents his reader with extensive analyses of Platonic dialogues that may be studied alongside the texts, Volume 3 of Order and History being an example. More frequently, however, Voegelin discusses Plato not by way of explication de texte, but rather in authoritative summaries of Plato’s meaning, presented both as self-evident interpretations of various passages in the dialogues, and also as instances of important elements of Voegelin’s own philosophy of consciousness.

My reason for emphasizing the difference between these two ways of discussing Plato is to point out what is perhaps best described as a rhetorical matter: the latter way is often presented as if it were the former (explication de texte) when it is not. More specifically, Voegelin’s use of terms such as epekeina and metaxy is not sufficiently grounded in the exegesis of Plato’s texts; despite his insistence that they were quite conscious and deliberate technical terms for Plato, they were not–at least, not in the sense that Voegelin claims.

Another reason for emphasizing the difference between these two interpretive strategies is to point out what I take to be a fundamental ambiguity in Voegelin’s treatment of Plato: the Plato of his textual exegeses, the subject of his analysis, is not quite consistent with the Plato of the philosophy of consciousness in which Voegelin uses Plato’s writings as a means to illuminate other subjects of analysis.

It is one thing to use Plato and the Gospels as ostensibly equivalent instances of a theophanic movement that can be counterposed to the modern egophanic movement represented by figures such as Hegel and Marx; but it is quite another thing to demonstrate their equivalence, without reference to a common inferior alternative, by means of sustained analyses of the dialogues and the Gospels themselves. And Voegelin’s attempts to do so in essays such as “Gospel and Culture”–for all their brilliance–always leave a reader with the impression that Plato is not quite up to the mark.

Is “Compact” to “Differentiation” as Philosophy is to Revelation?

Allow me to give just one example. In “Gospel and Culture,” Voegelin writes: “though Plato’s homoiosis theo is the exact equivalent to the filling with theotes by the author of Colossians, Plato’s spiritual man, the daimoniosaner, is not the Christ of Colossians, the eikon tou theou. Plato reserves iconic existence to the Cosmos itself (in the Timaeus . . .). Thus, the barrier becomes visible which the movement of Classic Philosophy cannot break through to reach the insights peculiar to the Gospel.”1

Voegelin’s broad comparisons of philosophy and revelation are usually more ambiguous than this passage suggests. A reader is often left with several contradictory impressions at once, all rather common in such sorts of comparisons, but seldom seen together: first, that Plato and a few other favored Greeks are being baptized; or that the superiority of Biblical revelation to philosophic noesis is being argued quite subtly, despite claims to the contrary; or the opposite, that the superiority of noesis to revelation is being argued subtly, despite claims to the contrary.

As evidence of the lingering impression of baptizing the Greeks, I mention only that the “leap in being” ostensibly performed by Parmenides, among others, was first performed by Kierkegaard as a “leap of faith.”2 And as evidence of the impression of the superiority of revelation, I mention only that the familiar argument concerning equivalent experiences, distinguished by degrees of compactness and differentiation, ultimately persuades no one about “equivalence” proper because it simply restates the superiority of revelation in a different set of technical terms.

In other words, the relation of compactness to differentiation is the relation of natural philosophy to supernatural revelation, or the relation of Classic philosophy, limited by the barriers of cosmos and polis, to the theology of the Gospels, maximally or properly oriented toward the divinity beyond the cosmos and cosmopolis. And if the scale of compactness and differentiation is not intended to carry this meaning, it is, then, a questionable bit of literary criticism.

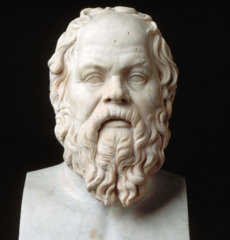

Finally, concerning the impression of the superiority of the Greeks: as Voegelin himself points out at the beginning of “Gospel and Culture,” some Christians are suspicious of any questioning whatsoever.3 My own reading is rather different. Far from arguing convincingly for their superiority, I think that Voegelin sells the Greeks short, if anything. Plato’s dialogues are more than merely equivalent to the Gospels; they are far superior, without the limitations Voegelin finds in them, and possessing resources he overlooks. Plato does not “[reserve] iconic existence to the cosmos itself,” though the Pythagoreans might have done so; and his daimonios aner, Socrates, is thankfully not the eikon tou theou, the Christ of the Gospels. But I anticipate the argument.

Voegelin’s Invention of Epekeina and Metaxy

Let me return to my earlier point: are epekeina and metaxy Platonic technical terms in Voegelin’s sense? I will discuss Plato’s use of epekeina first, and metaxy afterwards. Epekeina appears twice in the Republic (509b9, 587c1), and nowhere else in Plato.4 Its first use is in the dramatic or dialogic context in which Socrates attempts to instruct Glaucon, with little success, about the significance of the “good beyond being.” That there is an ultimate reality or divinity beyond the being-things of the cosmos is hardly a new insight, though it would be new for Glaucon to accept it as such.

What is important at this point in the dialogue is not this insight, but rather Socrates’ entire account of the good, in all its details; the shifting dialogic relation between Socrates and Glaucon; and the literary features used by Plato to present such matters, some of which indicate a great deal about how the Republic should be understood, as a whole and in relation to other dialogues.

In such a context, one cannot take Plato himself to be referring to anything like “the epekeina;” this formulation is, instead, Voegelin’s hypostatization of a single word, treating it as if it were a technical term carrying the full meaning of the passage and context in which it appears. It does not. The sense of something beyond the cosmos is there, of course, but hardly innovative, as I mentioned. And in hunting for such technical terms, Voegelin misses the full significance of the passage and its context.

One of the philological matters he overlooks about the word itself is quite interesting. The double use of epekeina in the Republic is deliberately intended to be part of a series of parallel terms. The good beyond being is contrasted to an extreme opposite: the worst possible pleasures, “beyond” even the bastard pleasures Socrates does mention, which the tyrant who has fled law and reason takes as his paradigm.

The contrast is obvious, but not worked out in all details in the Republic itself. The “flight” of the philosopher who takes the good as his “paradigm” is described in the Theaetetus (176a-7c).5 And the two opposed paradigms between which human beings live their lives are in turn described as “measures” in the Theaetetus and the Laws.

The paradigm of the good beyond being toward which the philosophic soul ascends is described as taking God as the measure in the Laws (716c-e)6; the paradigm of the worst possible pleasures toward which the tyrannical soul descends is described as taking a dog-faced baboon as the measure in the Theaetetus (161c). The Protagorean understanding of human being as the measure (frag. 1 D-K) is not a limiting paradigm7: it must give way to one or the other.

Obviously, many of the main features of this analysis have been captured in Voegelin’s account of the Laws, but the dialogues are far richer, and the philological implications far more suggestive–especially for ethics–than his account would suggest. To paraphrase Hegel’s remark about Schelling, Voegelin conducted his philosophical education in public, that is, in print. I intend no criticism with this remark, as Hegel did. But I do think that it should be admitted to be the case, because there is a good deal left to be done. Voegelin’s work is not complete in any philosophical sense, nor even complete as it stands, in that much of his textual analysis will have to be redone, if not undone.

The Apparent Change from Ideas to Symbols of Experience

Even Voegelin’s explicit self-corrections are not without their problems. There are two well-known instances: the first is Voegelin’s turn from the study of “ideas” to the study of “symbols of experience,” which led to Order and History as we have it; the second is the turn, between Volumes 3 and 4, from understanding history in the developmental sense associated with notions of linear time (at least concerning the history of what Jaspers calls the Axis-time period) to an understanding of history as the permanent presence of the mystery of human existence.

These two turns in his work are perhaps too readily taken at face value and too little analyzed. Voegelin’s frequent remarks notwithstanding, I do not think they are the decisive or pivotal events they are made out to be, in that the “new” understanding is quite evident in the earlier writings, and–what’s more important for understanding Voegelin’s account of Plato–in the later writings, the past “errors,” such as they were, are never completely overcome.

Consider the turn from “ideas” to “symbols of experience.” Is it a turn from words or abstract concepts to symbols, or from the intellectual generally to the experiential (and does the experiential include or exclude the intellectual)? And in what way does a symbol differ from an idea or a concept, given that Voegelin seems to identify a symbol with an author’s deliberate and conscious use of a specific word as a technical term?

Furthermore, one would assume Voegelin’s late, meditative writings to be the most attuned to experience and its symbolization, but this is not the case. His analysis of the “meditative complex” is focused on “consciousness:” the mind, and not the psyche in Plato’s sense. The components of consciousness are intentionality and luminosity: the former is a rather modern Husserlian epistemological category; and the latter, I believe, is taken from a dubious notion first developed in Augustine’s De magistro8 (11.37 ff.) as a response to the Roman philosophical schools, and too frequently used by Voegelin as little more than an experiential substratum for consciousness as intentionality.

Whatever type of experience luminosity might be, it seems to result in strictly intellectual investigations that in turn result in symbols, understood as neologisms, which differ very little from concepts or ideas. In my opinion, Voegelin’s account of intentionality and luminosity is not as insightful or precise in detail as Buber’s comparable account of “I-It experiences” and “I-Thou relations;” and Voegelin’s narrowing of the range of symbols to something like the set of all historically significant technical terms needs to be augmented toward, say, Northrop Frye’s more conventional definition of symbol as any feature of a text–from the placement of punctuation to the structure of the text as a whole–that is intended to convey the author’s meaning.

Voegelin’s Results are Nevertheless Platonic

What saves Voegelin’s account of the “meditative complex” and makes it comparable to Buber’s philosophy of consciousness is his use of Plato. He introduces the terms epekeina and metaxy to account for aspects of experience that cannot be covered by intentionality and luminosity. The resulting account is roughly Platonic in character, but only as a result. None of the specifics are strictly Platonic: there is no discussion of “consciousness” per se in Plato, nor of intentionality or luminosity; and the term epekeina is not a category, as I have mentioned.

Voegelin’s use of epekeina is intended to provide human consciousness with a “ground of being” that is more than a perspectival horizon. In Buber’s terms, the “ground of being” is the Eternal Thou; we might say God, simply. And Voegelin’s use of metaxy is intended to describe the nature of the relation between consciousness and the ground, among other things.

It is not immediately evident how luminosity, as Voegelin describes it, is related to “the epekeina” or God. Again, in Buber’s account there is no difficulty: the Eternal Thou stands at the end of a range of Thou-relations that might, in Voegelin’s terms, also be described as luminous experiences. In Augustine’s account, luminosity and God are related in the Christian manner, through the exclusive mediator: luminosity is possible as a supplement to intentionality only when Christ is accepted as savior. But in an attempt to avoid such specifically Christian formulations, Voegelin relates luminosity to God by means of “the metaxy.”

Like “the epekeina,” “the metaxy” is Voegelin’s hypostatization of a single word, treating it as if it were a Platonic technical term. But unlike epekeina, metaxy is quite a common term–a mere preposition or adverb, never (or hardly ever) a noun–that appears in a wide variety of passages and contexts: one hundred, to be precise (according to Brandwood’s Word Index).9 By no stretch of the imagination can the substantive matters of all the passages in the dialogues be related by the fact that the word metaxy appears in them.

To select an example at random: What has Homer’s way of making connections “between” his characters’ speeches (Republic 394b) have to do with what is “between” the midriff and the navel (Timaeus 77b4)? When Voegelin refers to the uses of metaxy in more obviously philosophic contexts, he finds only two; but the same problem arises: What has the realm of the number (arithmos) and form (idea) of things that is “between” the Anaximandrean poles of one (hen) and many (polloi), limited (peras) and unlimited (apeirian), mentioned in the Philebus (16c-17a), have to do with the daimonic realm “between” the gods and human beings, mentioned in the Symposium (202a)?10 There is no self-evident answer; and the substantive matters of the two passages cannot be related, much less identified, simply because the word metaxy appears in both.

Voegelin takes this even further in his article, “Equivalences of Experience and Symbolization.”11 After first hypostatizing metaxy and then using it interchangeably with the Stoic notion of “tension” (tasis), Voegelin goes on to claim that a large range of tensional experiences are strictly equivalent, in other words, identical: the metaxy is ostensibly evident in the tension between life and death, perfection and imperfection, time and timelessness, truth and untruth, amor Dei and amor sui, the moods of joy and despair, and a large number of similarly constructed pairs of antithetical terms.12

Quite simply, these pairs of terms describe widely different experiences, perhaps comparable in the context of a rather extensive philosophic anthropology; and to claim that they are equivalent because they have an antithetical structure that produces an “in-between-the-poles” in every case is to commit a rather obvious logical fallacy. I am fully in agreement with Voegelin that one of the most important tasks of the philosopher is to formulate a philosophic anthropology capable of analyzing the relations among the experiences expressed in such antithetical pairs of terms. But Voegelin’s account of the metaxy as a structure in consciousness is not up to the task. To paraphrase Max Scheler: Voegelin’s metaxy is only the road-sign, not the destination.

Voegelin’s Neglect of Eros

The extent of my agreement with Voegelin may not be immediately evident from these critical remarks. They are intended only in a constructive sense. I know of no clearer description of the human condition and the task of the philosopher than the first pages of Israel and Revelation, in which the “quaternarian structure” of the “primordial community of being”–God and human being, world and society–is discussed.13 And I know of no one who has done more to explore the mystery of human participation in the “order of being”–in its individual, political and historical dimensions–than Voegelin. But there remains a good deal to be done, and some of it requires us to reconsider Voegelin’s work in the same spirit in which he constantly reconsidered his own.

My concern at present is his philosophy of consciousness: in my opinion, its undoubted explorations of the “structures of consciousness” evident in the order of being are expressed in problematic ways; and these difficulties are less errors or oversights in textual analysis than the result of his preference for a critical vocabulary with inherent limitations. The terms in which Voegelin describes the “meditative complex” are less adequate to the task of accounting for the full range of human participation in the primordial community of being than are the accounts given in Plato’s Symposium, Buber’s I and Thou or Scheler’s Ordo Amoris, for example.14

The main difference is that Plato, Buber, and Scheler give primacy to eros in the exploration of the order of being; in other words, the primordial community of being is best described as an order of love, and its exploration is best described–even in its details–as an erotic activity of the psyche, and not as a tension in the relation of consciousness and reality.

In Voegelin’s philosophy of consciousness, “the metaxy” has yet another determination that deserves separate comment. Intentionality is the type of experience that counterposes subject and object; and luminosity is the type of participatory experience counterposed to intentionality. As I have suggested, one of the best accounts of the nature of, and relation between these aspects of existence is given in Buber’s I and Thou. Following Buber, I would say that the term “luminosity” makes no sense if it is taken to refer to something “between” the subject and object of the intentional or “I-It” experience.

Reading into Plato What isn’t There and Neglecting What is

At present, it is very fashionable to formulate “post-modern” critiques of modern scientific rationalism in precisely this manner, the best known of which is Gadamer’s hermeneutic philosophy. And yet Voegelin also uses “the metaxy” in this way on occasion. For example, in describing William James’ essay, “Does Consciousness Exist?” as “one of the most important philosophical documents of the twentieth century,” Voegelin states that its “fundamental insight” is its identification of what “lies between the subject and object of participation as the experience.” And then Voegelin is quick to equate this Jamesian “in-between” with both Plato’s metaxy and his own account of the luminosity of consciousness.15

Needless to say, there is nothing of such an understanding in Plato. The closest similar formulation is the description in the Republic (507c ff.) of truth (aletheia) as the light emanating from the good beyond being, illuminating the object of intellection for the nous just as sunlight illuminates the visible object for the eyes–a difficult passage to interpret, but obviously rather different in meaning from the notions advanced by James, Gadamer and even Voegelin.

Despite these difficulties in Voegelin’s philosophy of consciousness, it is nevertheless roughly Platonic in character. But it is Platonic in character only as a manifestation of Voegelin’s own character, and not as a result of any close textual analyses of the dialogues. As I have attempted to demonstrate, there are problems in Voegelin’s readings, even though he always seems to identify some of the salient points often overlooked by other commentators. But the greatest problem in his reading of Plato is what it passes over or leaves out entirely.

Most importantly, Voegelin’s ostensibly Platonic philosophy of consciousness provides no account of the virtues–quite a surprising omission, considering the fundamental importance of the account of the virtues in the dialogues. Where Plato discusses the capacities given in human nature, their development as virtues and their corruption as vices, Voegelin instead speaks only of a small range of unique experiences whose importance is more historical than ethical, in that they distinguish those who have had them from those who have not, or from those who refuse them in some way.

His favorite example is the distinction between “mortals” (thnetoi), the “spiritual man” (daimonios aner) and “fools” (amathes), which he finds in the Republic, Symposium and Laws, and claims is equivalent to the distinction in the revelatory tradition between those who have accepted revelation and those who have not, the insipient “fools” dismissed by the Psalmist and Isaiah.16 But the distinction between virtues and vices–that is, between the development and corruption of capacities common to all human beings–is simply not equivalent to the distinction between human beings who have had unique experiences and human beings who have not.

Ultimately a Philosophy Lacking Ethical Consequences

Similarly, what one learns about Socrates in the dialogues is not equivalent to what one learns about Christ in the Gospels. Virtue is not a conversion experience and vice is not a failure or refusal of such an experience; and the manifold differences between human beings in history can be analyzed far more accurately with terms that describe the various dispensations of universally given capacities than with terms that describe psychological and historical exclusiveness. Voegelin’s subsumption of Plato’s moral philosophy to categories ultimately derived from the revelatory tradition is more than a problem of textual interpretation: it has left his philosophy of consciousness without significant ethical consequence.

This was, of course, not Voegelin’s intent. If anything, his intent was just the opposite. The gradual “turn,” evident throughout his life’s work, from political science proper to meditative reflections is a turn away from the neutral, scientific objectivity claimed by the academic discipline toward the philosophic life; and the philosophic life is one dedicated to the cultivation of the virtues, the highest of which in Plato’s account are theoretical and practical wisdom, or the excellences of what might be called “consciousness.” For Plato, the psychic and noetic ascent toward the good beyond being is an activity undertaken primarily for itself, but also for its consequences: the ascent is a cultivation of given capacities, and its indirect result is a descent with greater virtue.

All comparable accounts of this ascending and descending movement–I have in mind mystical texts such as The Cloud of Unknowing, frequently mentioned by Voegelin–describe both the turn away from the world, in solitary meditative ascent toward the ground of being or God, and the primarily practical virtues consequent to the ascent that order the living of one’s life in the world and in relation to other human beings. Voegelin’s philosophy of consciousness provides an account of the ascent: consciousness moves toward and is ordered by “the epekeina” or God. But there is no descent. And without a properly grounded account of the virtues, his entire project threatens to become a strictly intellectual pursuit, and thus ultimately a merely academic matter. Without a return from the meditative ascent through ethics, there is no consequence for life.

Voegelin demonstrated such virtues in his own life, of course. That is not at issue. My point is that his philosophical anthropology, for all its brilliance, is insufficient. It remains an unfinished or incomplete aspect of his work. And in order to complete it, we must return to the primary sources–in the first instance, to Plato’s dialogues–in the spirit in which Voegelin read them; but we must avoid the problems of the manner in which Voegelin read them. Voegelin’s first “use” of the sources–his explication de texte–was groundbreaking. But only groundbreaking. Everything else remains to be done; and some things must even be redone.17

Notes

1. Eric Voegelin, The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, Vol.12, Published Essays, 1966–1985 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990), 194.

2. Eric Voegelin, Autobiographical Reflections, ed. Ellis Sandoz (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996), 79.

3. Eric Voegelin, The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, Vol.12, 173-175.

4. Plato, The Republic of Plato, trans. Allan Bloom (New York: Basic Books,1968).

5. Plato, Theaetetus, trans. Seth Benardete (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1984).

6. Plato, The Laws of Plato, trans. Thomas Pangle (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1980).

7. Jonathan Barnes, The PreSocratic Philosophers (New York: Routledge, 1982).

8. Augustine, Concerning the Teacher (De magistro) and On the Immortality of the Soul (De immortalitate animae), trans. George Leckie (New York: D. Appleton-Century Co., 1938).

9. Leonard Brandwood, A Word Index to Plato (London: W.S. Maney and Son, 1976).

10. Eric Voegelin, Order and History, Vol. 4, The Ecumenic Age (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1974); Anamnesis, trans. Gerhart Niemeyer (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1978).

11. Eric Voegelin, The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, Vol.12, Published Essays, 1966–1985.

12. Ibid., 119-120.

13. Eric Voegelin, Order and History, Vol. 1, Israel and Revelation (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1956), 1-11.

14. Plato, Symposium, in The Dialogues of Plato, trans. Seth Benardete (London: Bantam Books, 1986); Martin Buber, I and Thou, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1970); Scheler, Selected Philosophical Essays, trans. David Lachterman (Washington: Northwestern University Press, 1973).

15. Eric Voegelin, Autobiographical Reflections, 72-73.

16. Eric Voegelin, The Collected Works of Eric Voegelin, Vol.12, Published Essays, 1966–1985, 385-386.

17. My contribution to this reworking of Voegelin’s project to recover Plato’s philosophy can be found in the following texts: Zdravko Planinc, Plato Through Homer: Poetry and Philosophy in the Cosmological Dialogues (University of Missouri Press, 2003); “Ascending with Socrates: Plato’s Use of Homeric Imagery in the Symposium,” Interpretation 31/3 (2004), 325-350; “The Literary and Dialogic Form of the Sun, Line, and Cave Imagery in Plato’s Republic,” Eidos Research Group in Hermeneutics and Platonism, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Barcelona, Spain (2010), and Departments of Political Studies and Religious Studies, University of Prince Edward Island (2011); “Aristophanic Themes in Plato’s Republic: A Post-Voegelinian Reading,” forthcoming, Political Science Reviewer (2013).

Also available is “The Real Name of the Stranger: The Meaning of Plato’s Statesman,” “Plato’s Critique of ‘Platonism’ in the Sophist and Statesman,” “Challenging Plato’s Platonism,” “Plato Reconsidered: Planinc-Rhodes Correspondence,” “The Uses of Plato in Voegelin’s Philosophy,” and “One View of Zdravko Planinc’s Critique of Voegelin.”