There was a Boy They Called Hillaire

The Scorpion is black as soot,

He dearly loves to bite;

He is a most unpleasant brute

To find in bed, at night.

As everyone knows, many societies have at their root a song book or “hymnal,” familiarity with which unites the members of the club and divides “us” from “them.” The Chinese cherish the Shih Ching, or Book of Odes; devout Jews memorize Psalms (in Hebrew!); Greeks consider those ignorant of Homer as barbarians or Italians.

The point carries on a less grand level too: those who carry around Frank Sinatra in their memory are marked as a slightly different “civilization” than those who nostalgically hum the Ramones.

And, of course, when the members of these civilization-ettes (can we call them cosmia?) pass away, their “songbook” fades too, and declines from Music to a document.

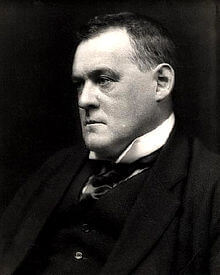

With this in mind, we may briefly consider that sole work of Hillaire Belloc, out of all he did, which still has cultural life.

The Cautionary Verses of Hillaire Belloc, first published as an anthology in 1939, comprised seven collections issued between 1896 and 1930. The illustrators were firstly B.T.B, that is Lord Basil Blackwood, and after, Nicolas Bentley.

What these verses are, are parodies of a Victorian tradition of cautionary verses directed at children, most famously the Struwwelpeter rhymes. Child misbehaves, child meets apocalypse. Let youth note and remember.

Belloc”s parodies, however, fire well over the heads of children at his real target: Victorian and post-Victorian English society, with its snobbery, self-satisfaction and bland cruelty. Under the sprightliness lies considerable venom: Belloc was a first class hater. He may have lived and written in England for the larger part of his life, but I suspect he never much actually liked the English and in this, I think, he differed from Chesterton, who knew that if you are going to satirize something you had better love it first.

It is among these verses that we find a cloud of characters once famous though the English speaking world:

Jim and his nurse and his lion,

There was a Boy whose name was Jim;

His Friends were very good to him.

Matilda,

Matilda told such Dreadful Lies

It made one Gasp and Stretch ones Eyes;

Henry King,

The Chief Defect of Henry King

Was chewing little bits of String

Lord Lundy, who cried, all the time; Tom and his pony Jack; Jack and his pony Tom; the tiger as a domestic apparatus; and our personal favourite, John Henderson:

John Henderson, an unbeliever,

Had lately lost his Joie de Vivre.

From reading far too many books

He went around with gloomy looks.

Despair inhabited his breast

And made the man a perfect pest.

The charm of this is more easily felt than defined. The verses are amusing, and pointed, and stick in the memory, with the aid of rhyme and lively meter. The illustrations, also envenomed, provide able back-up.

A digression: we have seen illustrations to some of these poems by the great Quentin Blake; Quentin Blake can do no wrong as far as we are concerned, but he does not reach the essential souls-of-suet power of the B.T.B.

Beyond this, these faux-fables have something of the insouciance, vitality, and heartlessness of fairytales.They are anything but PC. Sometimes, alas, they carry “anything but PC” a little farther than modern taste allows. In fact, there is note in the edition we have before us (London: Jonathan Cape, 1993) which reads, in part:

Although this book was first published in 1939, many of the poems and illustration [sic] were written and drawn during the Victorian era and reflect some of the attitudes and events of that period . . .

The publisher is afraid of his book.

“Mamma” said AMANDA “I want to know what

Our relatives mean when they say

That Aunt Jane is a Gorgon who ought to be shot

Or at any rate taken away

The generation which adopted these satires we may call the post-Edwardians — people born in the twenties who had to fight the second world war. Among these, the Cautionary Verses became well known and widely known. It may be that, although we certainly did not all read the same things, we read more of the same things than we do now. The father of someone we know used to recite them to his daughters, in the fifties, in Minnesota!

The verses remained popular, though less so in the generation after — the older boomers, if you will and this is natural — they had been read to by their parents. And even now, phrases sometimes still get dropped into the ongoing discourse of publications like the Times Literary Supplement, where they serve as signals to the reader of a shared tradition.

Through these generations, however, came a slow shift of attitude toward that bramble bush of history, power, and culture we may call Western Traditional Civilization.

The Victorians not only followed this tradition, rooted in Rome, they were fully of the opinion that they were that tradition. It was one substance, thank you very much.

The Edwardians, with a little more distance, welcomed it as an inheritance.

The post-Edwardians accepted it as a duty — the Edwardians told them they were supposed to.

To the Boomers it began to feel like an burden.

And, of course, generation Y has no opinion on the matter because nothing before 1985 matters in the least.

The Llama is a woolly sort of fleecy hairy goat,

With an indolent expression and an undulating throat

Like an unsuccessful literary man.

As much as we enjoy the Cautionary Verses, therefore, we suspect that their time is just about up.

Satire, said George Kaufman, is what closes on Saturday night, and these satires have had a longer run than most. The world does move on. The society satirized moves steadily closer to Lincoln”s time than to us. Meter and rhyme make the verse as foreign as Swinburne, and B.T.B. joins James Gillray and Isaac Cruikshank in the neglected volumes of history.

It is a pity but there it is.

And slowly answered Arthur from the barge

The old order changeth, yielding place to new

And God fulfils himself in Many ways

Lest one good custom should corrupt the world.