Try to Remember, Artfully

A few weeks ago, we touched on The Art of Memory, by Frances Yates, well known scholar of the Renaissance.

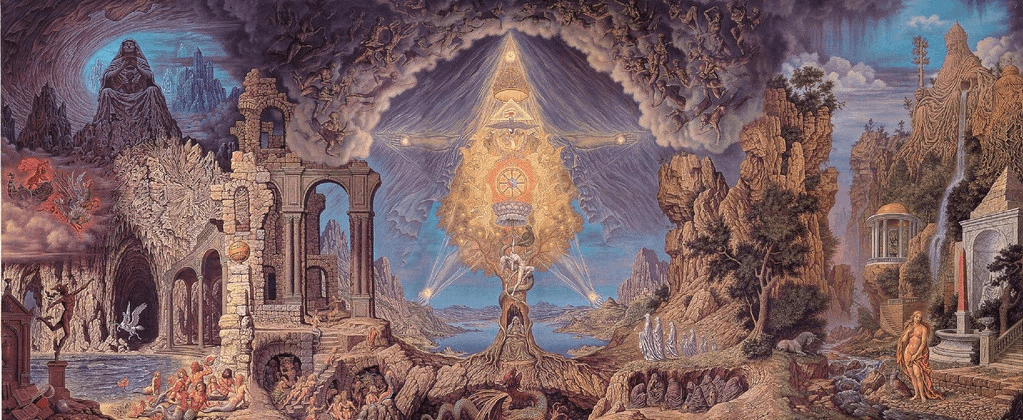

When that book came out in 1966, it caused some stir. Her subject, the history and kinds of mnemonics, was novel to the public; moreover she argued that the traditional use of these techniques fed, eventually, into the world of Renaissance magic, citing Giordano Bruno (a popular intellectual martyr) and even the Globe Theatre!

We make mention of The Art of Memory on this particular site, because it seemed to bear on EV’s studies of the somewhat louche roots of modern philosophy and scientism. Also because it is a neat topic.

In 1990, the subject was revisited, with a new slant and on a much larger scale, by Dr. Mary Carruthers of New York University.

It is this book,The Book of Memory, for which we now ask the indulgence of your consideration.

We plead two excuses.

The writer of this column found the book a profound shock, and has been mining the material in it for about ten years, we believe with profit. Hence, there is a simple missionary impulse operating here, the instinct to wave one’s arm at something and shout “Hey, look at that, fellas!”

Secondly, because it bears, I believe, on EV studies in three ways.

But, first, a brief summary of the book itself.

The matter is the use and influence of mnemonic techniques, from ancient times through the Middle Ages.

There are seven chapters.

The first two introduce the topic and its history, and discuss how the ancients and those of the Middle Ages thought of the mind (as far as memory).

Chapters three and four take up elementary memory design (there is charming material on Hugh of St. Victor) and the “arts” of memory.

Chapter five, a rather difficult section, ties memory and ethics together, and chapter six, still tougher, takes up memory and authority, and the role of memory in the creation of an “author,” that is, an authoritative text.

The last chapter, a little more relaxed, discusses how manuscripts were designed and marked up with a view to systematic recollection. Those who like to write in the margins of their own books (not library books, of course) will find this entertaining and edifying.

The Book of Memory is large and somewhat dry, and it covers a good deal of ground. If it has an overall thesis, it is that our ancestors thought, and thought that they should think, on rather different principles than we do. The point is illustrated by considering how we, and they, went about being “original.”

We find originality in tracking down a problem to its elements, reworking the elements, and then rebuilding from the new set of assumptions. The shining example of this technique is the creation of non-Euclidean geometry.

Implied in this approach is the ability to stand “outside” our own thoughts, and by objectifying them, controlling them.

Dr. Carruthers argues that the ancients and their successors built their originality on a deliberate basis of “remembering.” Originality, in their case, flowed from understanding a tradition and reworking it ad hoc and ad decorum, as it were.

The past, in their view, is not simply the past as available timber, much less something that has to be overcome—that exists, in fact, chiefly to be overcome—but the past as having an ethical claim on the present.

We do not use the past and what we have inherited. We are the past, and we are our inheritance. A similar theme, by the way, works in The Abolition of Man by C.S. Lewis.

All this bears on EV studies in three ways.

First, of course, it reflects on EV’s concern for “mindfulness”, as most famously developed in his remarks on Hesiod. “Remembering” is giving a fact an appropriate weight in one’s calculations.

Secondly, the mnemonic techniques outlined in the book have practical value, and we think they would be handy, among other things, for a better mastering of the huge amount of material that EV wrote. We humbly confess that at times we have trouble remembering which essay is which in the vast corpus Voegelinianum. There are indexes (very good ones, too) but nothing beats the index in your own mind.

Thirdly, consideration of this topic leads to a better understanding of the mental landscape of the famous writers on whom EV touches, that is, on their own experiences.

Not the least aspect of all this is one of Dr. Carruther’s subsidiary arguments: the use of mnemonic techniques requires not only establishing mental topoi but an emotional response to the subject at hand. Your columnist can testify that this does, in fact, greatly enhance the power of these tools.

Try this book . . . You’ll enjoy it. We found it a life-changer.

In our next essay, we would like to again consider Chesterton—as he appears to us from a distance of almost a century.

Finally, our apologies to all who were hoping for some barbeque on the Friday of the conference. We were ready, but flu intervened. One can only sigh, and reflect that’s its hardly the first time, and that no doubt lots of people in Honolulu had elaborate plans for that Sunday afternoon in 1941.