Utopian Forgetfulness of the Depth (Part II)

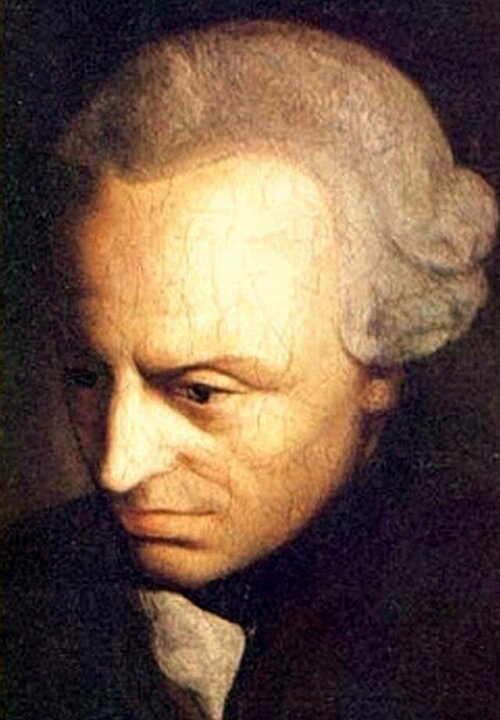

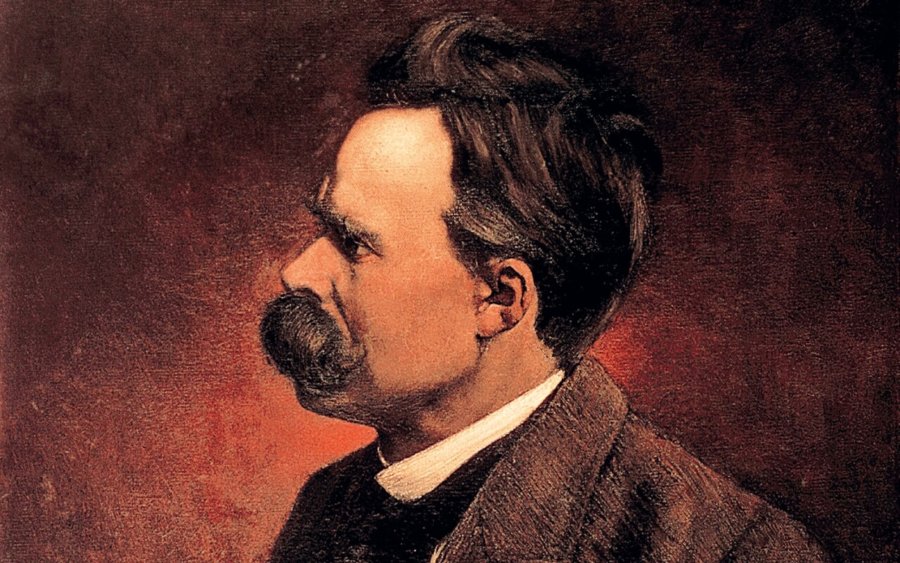

All of the critiques point toward the fundamental objection that Nietzsche was to express so powerfully. That is, that liberal politics had cut itself off from its own roots in philosophy and Christianity and had no comparable motivating appeal to put in their place. His prediction of its impending collapse has still not materialized but that does not negate the force of the warning that he has only been the most prominent in sounding.12 Without the formative spiritual traditions that produced order in the soul, liberal democracy seemed only to provide the outer shell that concealed the hollowness within. The liberal construction had merely been a secularization of the philosophic-Christian understanding of the person, but once it cut itself off from those roots it cut itself off from its own means of support. That step had been taken when the liberal ethos came to regard itself as self-sufficient.13

The process by which this self-subversion took place was, of course, gradual. Eighteenth-century liberals were still aware of the innovation they were taking in de-emphasizing the dependence of the legal order on its transcendent authorization. “Is there a possibility,” John Adams asks, “that the government of nations may fall in the hands of men who teach the most disconsolate of all creeds, that men are but fire flies, and this all is without a father? Is this the way to make man as man an object of respect? Or is it to make murder itself as indifferent as shooting plover, and the extermination of the Rohilla nation as innocent as the swallowing of mites on a morsel of cheese?” Even Robespierre is perhaps not disingenuous when he declares that a legislator cannot be an atheist since he depends on a “religious sentiment which impresses upon the soul the idea of a sanction given to the moral precepts by a power greater than man” (quoted in Arendt, On Revolution, 192). Such observations strike a particularly somber note when read, as Hannah Arendt suggests, from the perspective of our own “ample opportunity to watch political crime on an unprecedented scale, committed by people who had liberated themselves from all beliefs in ‘future states’ and had lost the age-old fear of an ‘avenging God’ ” (192).

Yet it was not the intention of the liberal founders to lead us into the nihilistic wasteland. They were convinced, with considerable justification, that a public order could be erected on the basis of the human capacity for self-government, and that the experience of self-responsibility would be sufficient to promote the virtues that would be necessary to sustain it. A liberal public order would not have to depend on any overtly transcendent grounding, although it would certainly draw on the virtues that continued to be formed through the uninterrupted influence of the Christian churches. The virtues required in the public order could be derived from this indirect source and immediately from the practice of liberal politics itself. This is the genius, Arendt insists, of the American founding that recognized that “it was the authority which the act of foundation carried within itself, rather than the belief in an Immortal legislator, or the promises of reward and the threats of punishment in a ‘future state,’ or even the doubtful self-evidence of the truths enumerated in the preamble to the Declaration of Independence, that assured stability for the new republic” (200).

The act of foundation develops its own legitimacy. Auctoritas in its original meaning, Arendt explains, is to augment and preserve what is already there. She looks back to the Roman parallel in the convergence of authority, tradition and religion. Religare always meant to bind oneself back to the order that had already been there and in the process to augment and preserve it in the present. The authority is therefore derived from the practical reevocation of the tradition today. “From this it follows that it is futile to search for an absolute to break the vicious circle in which all beginning is inevitably caught, because this ‘absolute’ lies in the very act of beginning itself” (205). There is no beginning that does not itself derive from a beginning that is not already there, but in the taking of action both its beginning and its principle are rendered transparent. “What saves the act of beginning from its own arbitrariness is that it carries its own principle within itself, or, to be more precise, that beginning and principle, principium and principle, are not only related to each other, but are coeval” (214).

The American innovation, on this view, was the separation of power from sovereignty. It was no longer necessary to rely on a source of absolute sovereignty, with its transcendent valorization, as the only reliable locus of political power. For the Americans such absolute sovereignty was not even properly speaking power. It was no more than a paltry imitation that had usurped the only genuine power that is derived from the reciprocal and mutual agreement of individuals. The necessity for joint action had taught them that “power comes into being only if and when men join themselves together for the purposes of action . . . . Hence binding and promising, combining and covenanting are the means by which power is kept in existence” (174). The division of power, far from weakening it, was the indispensable means by which it was strengthened through the necessary conjunction of wills in its exercise.

Yet despite the formidable force of this conviction in the foundation of the American regime, its clarity has generally not been sustained. With the exception of the Supreme Court, whose authority is derived from its continuity with the founding actions, itself “a kind of Constitutional Assembly in continuous session” (Woodrow Wilson, quoted 201), the public space for freedom of action has shrunk markedly in the American and all other modern states. In language strikingly similar to Oakeshott’s strictures against the state as enterprise association, Arendt complains of the overwhelming of the political with the demands of the social. The latter represents the dominance of production and consumption, which arises when politics admits the exigencies of man’s physical necessities as its primary concern. Such an invasion is invited through compassion, but it becomes virtually irresistible under the pressure of the modern technological reduction of all activities to their instrumental value.

The root failure she sees as the inability of the liberal revolution to ensure a continuing space for public action, once the revolutionary action itself had passed. There was no longer an arena in which the citizens could act in the same concerted manner as in the assertion of their political liberty. All had contracted to the preservation of civil liberty, the private pursuit of happiness. Arendt singles out the neglect of the townships, with their communal self-government, as pivotal to the loss of the public space within which free political action is possible. The pattern is repeated in all the modern revolutions where the spontaneous self-organization of society into councils or wards is quickly suppressed in the name of the efficiency of national or central order. This may have been an effective way of marshaling the resources of society toward the collective welfare, but becoming the blind instruments of the governing elite did nothing for the self-responsibility of the citizens. “Wherever knowing and doing have parted company, the space of freedom is lost” (268).

The astonishing aspect is the illusion that nevertheless a liberal political order can survive. Even the preservation of civil rights, the guarantee of being left alone without paternal interference in the running of our own lives, presupposes the recognition that human beings ought to be responsible for themselves. The possibility of sustaining the practice of political self-government can hardly survive the disappearance of all substantive opportunity for the exercise of common political action. If the people are no longer free, but only their representatives, then it can hardly take much time for the sense of self-responsibility itself to disappear. They cease to be individuals who are capable of making their own decisions and willing to participate in the deliberative pursuit of their common good. Instead they sink to the level of the mass man, an obstreperous bundle of impulses and passions, who can no longer be swayed by rational argument but must be manipulated by the techniques of behavioral control in the panoply of forms created by the twentieth century.

Without membership in a variety of self-governing intermediate institutions, the individual is reduced to the isolated atomistic membership in the mass. Nothing intervenes between this disconnected individual and the sovereign government at the top. Besides the radical lostness and loneliness of such individuals, whose identity is increasingly defined by their relationship to the abstract government above them, they are particularly disadvantaged by the lack of any experience in public action by which to measure the events around them. It is the state of utter disorientation that Arendt had earlier diagnosed as the fertile ground for totalitarianism. The experience is that of the individual who is not only politically isolated but also fundamentally lonely, without the contact with other men that would confirm his identity and their common sense of a common world. All that remains is the capacity for logical reasoning working away on the abstractions of ideology. “It is the inner coercion whose only content is the strict avoidance of contradictions that seems to confirm a man’s identity outside all relationships with others” (The Origins of Totalitarianism, 478).

There is an eerie familiarity to Arendt’s description of the superfluous individuals who, lacking membership in any tangible community, exhibit a “passionate inclination toward the most abstract notions as guides for life, and the general contempt for even the most obvious rules of common sense” (316). We recognize the disturbing echoes of our own mass democracies in which the anonymous television audience is manipulated by the media and political elite to generate an emotional activism about such grand national issues as the budget deficit or health care reform. The problem is not that the issues are not real, but that the citizens lack any meaningful frame of reference within which to judge them. Even when the issues are of a more concrete nature, as in the numerous moral failings of public figures, the public reaction is often so shrilly moralistic that it bears no relation to the common sense acceptance of an imperfect world. The important thing after all is whether a political representative is competent to fulfill the duties of his office. But without the experience of concrete participation in responsibility how can we expect voters to act on the basis of a realistic assessment of the circumstances?

Unsustainable Without Tradition

The unsustainability of a liberal order is driven home in the baldness of the assertion that it is a tradition that is not a tradition. This gives rise to the improbable expectation that the unfolding of liberal democracy, which the originators considered to require a most fortunate blending of moral and political conditions, can be counted on to continue its autonomic progress indefinitely. It is the one practice that does not need to be sustained through the practice of it. Instead, it provides the overarching neutral framework within which competing traditions of the good must struggle toward realization, but the liberal state itself exists in splendid impregnability beyond the fray. That is because there is no liberal good toward which it strives and because there are no liberal virtues on which it depends. The liberal order itself is not threatened because it has become a wholly permeable medium.

The bursting of the bubble of liberal neutrality and independence is, as we saw in Chapter 1, the core of the crisis currently afflicting it. The increasing inability of liberal politics to sustain itself has made it painfully aware both of the degree to which it depends on a certain conception of the good and that it cannot survive if liberals no longer experience this orientation as good. Such compulsory self-examination does not, as we saw in the last chapter, mean that the liberal construction is evacuated of all moral authority. It still contains the residue of moral truth that has sustained it from the beginning, and it has shown itself through history to be capable of remarkable efforts of resuscitation. But now it is called to move beyond such ad hoc rejuvenations by articulating the existential depth from which it has always drawn its inspiration. The previous liberal strategy of remaining silent about the roots of its own conviction can no longer work because the erosion has now reached the point where skepticism about its convictions is rampant. Is there a liberal good?

In this chapter we have examined why contemporary liberals are not well placed to deal with this question. They have played the neutralist tune for so long that it is doubtful they have any other notes. Indeed, they have shown themselves captive to those very liberal tendencies that in the past have mitigated against any prolonged meditation on what inspired it. An unreflective sense of their own evident rightness and an inclination to believe in historical progress conspired to remove the urgency to attend to the existential underpinnings of liberal order. But now that such comforting illusions have begun to lose their hold, the question is whether liberals are up to the task of articulating an account of the good that has guided them. Can we expect an evocation of the liberal tradition of the good from thinkers who have never properly understood the nature of a tradition?

Alasdair Maclntyre is not sanguine about the possibility. Liberal theorizing began as the attempt to define a tradition-independent morality that would be universally compelling irrespective of circumstances. The result has been that “liberalism, which began as an appeal to alleged principles of shared rationality against what was felt to be the tyranny of tradition, has itself been transformed into a tradition whose continuities are partly defined by the interminability of the debate over such principles” (Whose Justice? Which Rationality? 335). It has become the tradition whose essence is its self-negation as a tradition. This is, as Maclntyre perceptively explains, the function of its emphasis on the heterogeneity of goods, on the individualism of the actor, of the indecisive making and unmaking of decisions, and of the continuous philosophical debate on principles that is always promising but never conclusive. All the features work to preserve the liberal tradition of autonomous self-determination but in such a way as to render its validity inherently unstable. What, after all, is the value of promoting self-responsibility if all of the justifications proffered seem to dissolve into incoherence?

Everything turns on the possibility of liberal society recognizing what it means to acknowledge its own dependence on a tradition. The liberal order would have to acknowledge that the liberal failure to elaborate a self-evident neutral ground is “by far the strongest reason that we can actually have for asserting that there is no such neutral ground” (346). Nothing can be established on the basis of its plausibility to individuals of every conceivable persuasion and none. Nor can we expect that the strenuous efforts required to sustain a liberal democratic order will be forthcoming if its appeal is only to the mixture of episodic altruism and recurrent self-interest that is the prevailing image of its citizens. Moral and political order does not exist in the bare skeleton of promises and contracts. It is rather the living conviction of the necessity of having and abiding by agreements that makes them possible and is the real source of their life. The explication of a liberal order consists in the thematization of the living tradition that underpins it.

The difficulty with this recognition is that its articulation will involve a transformation of the liberal self-understanding as a nontradition. It will necessitate the recognition that the liberal conception can be sustained only if it recognizes itself as a tradition that is willing to defend itself against the alternative traditions posed against it. The way to consolidate liberal convictions is not to abandon the conflict of positions as an irresolvable clash of perspectives but to engage in the dialogue as rationally and comprehensively as possible. Maclntyre clarifies the nature of a rational tradition as one that is willing to confront epistemological crises, acknowledge what is valid in its rivals’ critiques, rearticulate its own principles in such a way as to take account of them, and then elaborate an account of order that demonstrates its superiority over its rivals. He concedes that the dialogue does not always extend so far, but he insists that the possibility of its rational resolution must be preserved.

The alternative is the perspectival claim that no tradition can vindicate its claim to truth. That recurrently liberal proclivity “fails to recognize how integral the conception of truth is to tradition-constituted forms of enquiry. It is this which leads perspectivists to suppose that one could temporarily adopt the standpoint of a tradition and then exchange it for another, as one might wear first one costume and then another, or as one might act one part in one play and then a quite different part in a quite different play” (367). That is the pathology of the “nomadic thinker,” whose homelessness would prove fatal if it engulfed a whole society. What sustains a tradition is the conviction that it is true or right, and that cannot survive if the possibility of truth itself is abandoned. Truth must remain the measure, even if it is not fully attainable, if the seriousness of the quest is to be preserved.14

The great strength of Maclntyre’s analysis is his insistence on the presupposition of truth as a necessary precondition for the viability of a tradition. “Only those whose tradition allows for the possibility of its hegemony being put in question can have rational warrant for asserting such a hegemony. And only those traditions whose adherents recognize the possibility of untranslatability into their own language-in-use are able to reckon adequately with that possibility” (388). If liberal order bases itself on the confession of the impossibility of truth, then its public hegemony is a hegemony of power and like all such assertions inherently unstable. It cannot rest its authority on the claim to truth but must perpetually guard against the raising of the question of its own legitimacy. Only a tradition that is willing to put its own hegemony to the test of truth can acquire the stability of rational self-confidence.15 With traditions as with everything else, only those who are willing to lose their lives will save them.

The challenge is to admit that the testing of the truth of traditions opens us up to the testing of ourselves as well. It involves the more substantive risk of our own self-exposure in light of the truth disclosed by traditions. Not only do we test the traditions but the traditions in turn test us as well. That acknowledgment is crucial to the possibility of establishing their claim to authority. There is no neutral language into which all the rival claims to truth can be translated; the greater cogency of one calls into question the validity of another. There is no Archimedean skybox from which to view the debate. We are involved with the contest, and it is the coherence, rationality, and reality of our way of life that is at stake. The only means available to us for rendering a judgment about the truth or falsity of the various positions is through our own struggle toward truth. The only method available to us is the testing of the claims in the juxtaposition of what Dostoyevsky called the truth of “living life.”

The notion that we are in possession of a means of evaluating truth that does not involve our own inchoate struggle toward it is one of the great distorting conceptions of our world. “This belief in its ability to understand everything from human culture and history, no matter how apparently alien, is itself one of the defining beliefs of the culture of modernity” (385). It is evident in the conceit that all the richness of traditional meaning can be captured through our meager placement of them in museums, lists of great books, or under the impoverished rubrics of aesthetics. The governing assumption is that all historical wisdom can be absorbed in ways that do not fundamentally challenge the shallowness of our own world. The culminating expression of this approach is reached in contemporary deconstructionism, which no longer even regards texts as wholes and permits us to interpret them freely without any controlling reference to historical context or authorial intention.16

Recognition of their untranslatability into contemporary language pulls us up sharply against the limitations of our modern worldview. It reminds us of the existential depth from which all symbolization arises and knocks the supports from the modern conceit that we can have a language that presupposes nothing. All constructions of meaning, even the minimal constitution of liberal neutrality, arise from the way of life through which liberal meaning is rendered transparent. Without reference to the practice of the tradition we can neither make sense of nor sustain the meaning subscribed. The hermeneutical challenge then becomes not finding a philosophical Esperanto in which the least common denominator can be expressed but testing that our own existential-symbolic horizon is rich enough to include all the types it seeks to interpret. If our own tradition of meaning is not up to the level of the texts we attempt to read then we face an impasse. It can be broken only if we permit the texts of our inquiry to expand our horizons sufficiently to include them.

At that point we will, in Maclntyre’s conception, have taken seriously the nature of a tradition. We will have entered at least imaginatively into the way of life of a tradition and acquired the basis from which to understand the rationality that forms its coherence. Rather than going along with the typical liberal tactic of “reformulating quarrels and conflicts with liberalism, so that they appear to have become debates within liberalism” (392), we will have taken the first step of putting liberal conviction itself to the test and thereby evoke its own living foundations. That will be the indispensable means by which substance is restored or perhaps rediscovered in the hitherto hollow appearance of liberal principles. The way will then lie open to the recognition that liberal practice too is a tradition and that it is sustained principally through its capacity to evoke existential order within its adherents.

The story of the liberal persuasion has been the story of its progressive amnesia toward its own sources. The sequel of its recovery must follow the correlative path of an anamnestic rediscovery of its own inspiration. As Oakeshott and Arendt (and Rawls and Rorty in their own way) emphasize, liberal order is a practice that is sustained by the virtues endemic to the practice itself. More important than any principles or foundations beyond liberal order is the reality constituted through the engagement with individual and communal self-government. That is what forms the core of the liberal tradition, and its continuance depends on that recognition. Like every tradition, liberal order must insist that it can be understood only from within and refuse to concede the interpretation placed from the outside. Participation in it, also like other traditions, must be conditioned on the ability and willingness to enter into its way of life. The exercise of authority must be strictly limited to those who have clearly demonstrated their virtue in sustaining the tradition’s order. Only in this way is it possible to preserve an order that, not being something that can be maintained indifferently by every human type, depends for its flourishing on the capacity to evoke those qualities in its citizens that are its living foundation.17

Insufficiency of Critique

The problem with the recommendation that liberal politics acknowledge its own dependence on a tradition is that Maclntyre does not seem to think it can be taken seriously. He does not appear to believe that liberal practice is capable of understanding its historical unfolding. The liberal mind-set is too unalterably opposed to the whole notion of a tradition, in his view, for it ever to acknowledge its own self-constitution in-depth. Instead, he looks to the liberal encounter with more substantive rational traditions to bring about first “an awareness of the specific character of their own incoherence and then accounting for the particular character of this incoherence by its metaphysical, moral, and political scheme of classification and explanation” (398). This is also the reason that he is somewhat vague about how this transformation of the liberal tradition into one of the earlier, more coherent traditions is possible. He allows as it is likely to come about only through a fundamental “conversion,” since it will involve the detached liberal self becoming “something other than it now is, a self able to acknowledge by the way it expresses itself in language standards of rational enquiry as something other than expressions of will and preference” (396-97). How such a conversion might come about and how the process might be set in motion are considerations beyond the limits of Maclntyre’s reflections.

In this regard he is representative of a very formidable movement of thought that has been gaining momentum since the beginning of the century. The discovery of the richness and depth of premodern philosophical traditions, such as the classical and the medieval, has convinced many thinkers that only the infusion of truth from these sources can save the liberal ethos. Left to itself, the tradition remains irretrievably bankrupt. This is particularly the conclusion of the generation of European emigres, such as Leo Strauss and Eric Voegelin, who witnessed the corruption and disintegration of liberal democratic regimes before the onslaught of totalitarianism. Arendt, too, often sounds as if she is speaking from a Greek perspective, with her emphasis on the immortality of publicly effective action. The long-standing Catholic critique of liberalism from Leo XIII to John Paul II is similarly rooted in the conviction of the superiority of natural law and solidaristic perspectives over liberal atomistic individualism.

They are all friendly critics of liberal democracy in the sense that, unlike the now largely defunct revolutionary ideologies, they wish to see it improved rather than abolished. Like the Canadian critic George Parkin Grant, they concede that the liberal construction is “the only political language that can sound a convincing moral note in our public realms” (English-Speaking Justice, 5). But they cannot see any way that the moral residue of liberal order might be coherently expanded to secure it against its inherently centrifugal tendencies. Only one of the traditions with “more substantive presuppositions of truth” possesses the requisite durability to withstand the corrosive relativism of egalitarianism. A tradition requires the fortitude to be able to insist that not everything within it is equally accessible to everyone, if it is to preserve the conditions in which the substantive rationality of practice can be maintained. In most respects the liberal tradition struck its most serious friendly critics as a poor candidate for the position. It is simply too difficult for the emphasis on individual autonomy to be corralled by the authoritative requirements of a practice.

Yet despite the evident merit of this assessment, it is also difficult to avoid the suspicion that the evaluation too is tinged with a certain utopianism. True, the charges directed against the liberal construction are largely valid, and the greater cogency of premodern spiritual and philosophical traditions is indisputable, but is there not an element of escapism secreted in the very heightening of the contrast between such juxtapositions? A trenchant critique of liberal politics is an indispensable first step, but can the meditation afford to rest there? It is almost as if the critics have given up entirely on the effort to remediate the liberal framework from within and are now confined to recording its inexorable descent into the maelstrom. One is struck by the absence of much serious reflection on how liberal self-understanding might be modified to accommodate the critics’ insights. An impression is conveyed of having already abandoned the effort at remediation.

This is a perpetually tempting possibility, especially for those who have reached a personal viewpoint of greater meaning and depth. The task then becomes to find a modus vivendi that will enable the life of reason to be carried on in a world that is pervaded by unreason; the challenge to do what one can to bring about a growth of the soul within that world is declined. The tendency to dismiss responsibility is increased by the very power of the critique of liberal hollowness, which strongly reinforces the sense of the critics’ own superiority to contemporary vacuity. Whether reading MacIntyre, Strauss, Voegelin, or Arendt, one comes away with a very strong sense of the power of the Platonic or Thomist viewpoint on the world and of how paltry the confused gropings of modern liberal philosophy really are by comparison. There is little encouragement to consider the substantive achievements of liberal order or to think through the way it might be internally redirected to overcome its manifest defects. Even the realization that the liberal conception is the only option available to us for the foreseeable future is not often made.

Such blithe dispensation creates the air of unreality that Rorty has pilloried as “terminal wistfulness” in the various shades of communitarianism. Without some concrete indication of how liberal democracy might be nudged toward the transformation, it is difficult to resist the conclusion that the discussion has been merely an exercise in longing for an irrevocably vanished past. After all, what is the purpose of reflecting on the superiority of the premodern traditions if it is not to draw them into this world as a source of order? If that is the intention, then some attention must be given to the question of how capable the liberal ethos is of absorbing such insights and how the insights might be organically promoted within the liberal construction. A mere assertion of premodern truth, without any attempt to mediate it in language that renders it minimally intelligible from a liberal perspective, would be futile. A way must be found to give the philosophic-Christian tradition a public voice; otherwise, it will go the way of all traditions compelled to shrink to a wholly private level.

It is one of the principal contentions of this study that such a means is available, although not sufficiently recognized, in the traditionalist critique itself. The very act of critique contains within it the implication of what is required to remediate the defects. By undertaking the resistance and diagnosis of what is at fault within the liberal polity, we correlatively evoke a vision of the alternative that would overcome it. The therapeutic growth of the soul is the means by which disorder is defeated by order. That process is, moreover, not one that occurs simply in the critics of liberal thinking but is, as we have seen, an unfolding that has also emerged from the crisis within liberal society itself. The analysis of the critics and the self-diagnosis of the liberal tradition are convergent, even if they are not coincident. They provide the opportunity for the critics to inject their more profound diagnosis at a stage within the intraliberal conversation that will enable the dialogue to move forward toward a horizon beyond the contemporary liberal preserve. This suggestion is simply another way of stating Maclntyre’s account of how one tradition manages to integrate its rivals “in such a way as both to correct in each that which … by its own standards could be shown to be defective or unsound and to remove from each, in a way justified by that correction, that which barred them from reconciliation” (Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry, 123).

The difference between my approach and Maclntyre’s is that I do not consider the liberal conviction to be an unalterable fixed quantity. I take seriously the suggestion that it is a tradition and that, like all traditions, it rests not on its overt formulations but on the underlying resonances that give its principles life. Thus, the possibility remains of expanding the admittedly limited existential base that now underpins liberal order. By building on the fragments that still constitute a liberal tradition, it is possible to discover the firm reality on which to build a greater development. Anything else, as Oakeshott has reminded us, will be utterly ineffectual. It would comprise only the erection of a superstructure on a foundation of air, unconnected with the real living world of human beings today. The principal object of this study is to show how such a meditative expansion within liberal politics can take place. Beginning with a reflection on the state of crisis within liberal theory and practice, we move through a consideration of the nature and source of the crisis to a realization of the direction that must be pursued in its resolution. It is crucial that we at no point depart from the liberal self-understanding. The outcome is then one that, even if it is several stages removed from the contemporary liberal conception, is intimately connected to it as its own meditative unfolding. It cannot be disavowed by the liberal mind, and it provides a trajectory of the way by which the liberal tradition itself might be transformed.

The first stage has consisted of the self-recognition of the crisis and the outline of the parameters in which the liberal order is both an enduring source of moral authority and incapable of acknowledging the depth of conviction from which it springs. The next stage is to delve more deeply into the liberal tradition to discover what resources might be available to renew it from within. This will begin naturally with a reflection on the source of the liberal contradiction between its convictions and their acknowledgment, which seems to be the core of the instability of the whole construction. Why is it that liberal conviction is so constitutionally incapable of mounting a coherent defense of the principles that it so manifestly holds? With that deeper understanding of its nature in mind, it will then be possible in the third stage of the meditation to take account of the limitations and strengths that conjoin to form the liberal tradition. In that way we will have a means of exploring the extent to which the limits can be expanded and the strengths exploited to constitute a more substantively moral politics. The conversion that Maclntyre and others look to must, like all true conversions, occur within the soul of the penitent.

Notes

12. It is interesting to note that Pope Leo XIII issued the same kind of warning at almost the same time in his 1888 encyclical on liberalism, Libertas Praestantissimum; the text is available in The Church Speaks to the Modern World: The Social Teachings of Leo XIII.

13. A similar objection to the brittleness of liberal rhetoric seems to be the essence of the communitarian critique. Liberalism teaches respect for the distance of self and ends, and when this distance is lost, we are submerged in a circumstance that ceases to be ours. But by seeking to secure this distance too completely, liberalism undermines its own insight. By putting the self beyond the reach of politics, it makes human agency an article of faith rather than an object of continuing attention and concern, a premise of politics rather than its precarious achievement. This misses the pathos of politics and also its most inspiring possibilities. It overlooks the danger that when politics goes badly, not only disappointments but also dislocations are likely to result. And it forgets the possibility that when politics goes well, we can know a good in common that we cannot know alone. (Sandel, Liberalism and, the Limits, 183).

14. It is interesting to note the degree to which John Paul II has emphasized the constitutive role of truth in his most profoundly philosophical encyclical on the crisis of morality, which is appropriately titled Splendor Veritatis.To the affirmation that one has a duty to follow one’s conscience is unduly added the affirmation that one’s moral judgment is true merely by the fact that it has its origin in the conscience. But in this way the inescapable claims of truth disappear, yielding their place to a criterion of sincerity, authenticity and “being at peace with oneself,” so much so that some have come to adopt a radically subjectivistic conception of moral judgment, (par. 32).

15. This is a point earlier developed by Wilmoore Kendall. The proposition that all opinions are equally — and hence infinitely — valuable, said to be the unavoidable inference from the proposition that all opinions are equal, is only one — and perhaps the less likely — of two possible inferences, the other being: all opinions are equally — and hence infinitely — without value, so what difference does it make if one, particularly one not our own, gets suppressed? This we may fairly call the central paradox of the theory of freedom of speech. In order to practice tolerance on behalf of the pursuit of truth, you have first to value and believe in not merely the pursuit of truth but Truth itself, with all its accumulated riches to date. The all-questions-are-open-questions society cannot do that; it cannot, therefore, practice tolerance towards those who disagree with it. It must persecute — and so, on its very own showing, arrest the pursuit of truth. (“The ‘Open Society’ and Its Fallacies,” reprinted in John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, 154-67).

16. MacIntyre quotes (Whose Justice? Which Rationality? 386) the following illuminating passage in which Roland Barthes rejects the possibility of a coherent, contextually relevant meaning to texts.

That is not the case with a work (oeuvre): the work is without circumstance and it is indeed perhaps what defines it best: the work is not circumscribed, designated, protected, directed by any situation, no practical life is there to tell what meaning to give to it . . . in it ambiguity is wholly pure: however extended it may be, it possesses something of the brevity of the priestess of Apollo, sayings conforming to a first code (the priestess did not rave) and yet open to a number of meanings, for they were uttered outside every situation — except indeed the situation of ambiguity. . . .” (Critique et Verité, 56)

“This is a splendid description,” Maclntyre goes on to observe, “of what traditional texts detached from the context of tradition must become, presented by Barthes as though it were an account of how necessarily texts always are” (Whose Justice? 386).

17. Charles Taylor has recently provided an excellent sketch of just such an approach, in which he sympathetically takes up such contemporary liberal preoccupations as respect for difference and multiculturalism, but points out that their realization depends on the presence of a common horizon of meaning.

To come together on a mutual recognition of difference—that is, of the equal value of different identities — requires that we share more than a belief in this principle; we have to share also some standards of value on which the identities concerned check out as equal. There must be some substantive agreement on value, or else the formal principle of equality will be empty and a sham. We can pay lip-service to equal recognition, but we won’t really share an understanding of equality unless we share something more. Recognizing difference, like self-choosing, requires a horizon of significance, in this case a shared one.” (The Ethics of Authenticity, 52)

This excerpt is from The Growth of the Liberal Soul (University of Missouri Press, 1997). It is the second of two parts, with part one available; also see “The Growth of the Liberal Soul”: part one and part two” and part three.