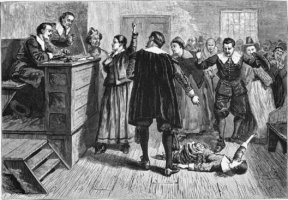

Were the Salem Witches justly Hanged?

On February 29, 1892, a large audience gathered at the Essex Institute in Salem, Massachusetts to reconsider the infamous Salem witch trials from the distance of two hundred years. One of the speakers, Harvard Professor of English Barrett Wendell, rather shockingly suggested that the condemned witches deserved their fate. It was, more often than not, their “moral due.” Wendell based his conclusions on experience with contemporary occultism and the demanding nature of seventeenth century Puritanism. The trials were not an example of religious intolerance or material greed, but the genuine presence of evil in Salem.[1]

Wendell stalked Harvard yard for decades with the likes of faculty colleagues like Irving Babbitt and George Santayana. Born into a wealthy family blessed with that most Brahmin of names – Oliver Wendell Holmes was a cousin – Wendell failed at a legal career but found his real calling in the classroom, teaching composition in Cambridge for thirty-seven years and influencing two generations of students, including W. E. B. DuBois and T. S. Eliot. Indeed, his influence lingered for years after his 1921 death. His 1891 English Composition remained in print through the 1940s. Wendell left behind a host of books, some collected speeches like Stelligeri (1893), The Temper of the Seventeenth Century in English Literature (1904), and Liberty, Union, and Democracy (1906), as well as stand-alone volumes, most famously his magisterial Literary History of America (1900). His particular interest, however, was New England Puritanism, as witnessed by his 1891 biography of Cotton Mather. In Puritanism, Wendell saw the usable past and historical precedents from which to critique the political, social, and cultural abuses of an industrialized democratic America. If Henry Adams and Ralph Adams Cram looked to Gothic cathedrals for succor, Wendell turned to the humbler environs of the New England meetinghouse.[2]

The second half of the nineteenth century brimmed with interest in psychic phenomena. Beginning with Christian Science, mind-healing, and New York’s famous rapping Fox sisters (who claimed contact with the dead through mysterious knocking from walls and furniture), the spiritualist movement expanded after the Civil War, as many Americans sought encounters with sons and fathers who died on Southern battlefields. Séances and trance sessions became highly popular, often led by women who saw their role as medium as an important source of social leadership in the years before full suffrage. Critical scientific investigations of the new occult made little progress in lessening its appeal. In March 1889, the New York Sun reported:

“The tendency to refer material results to supernatural causes seems to increase rather than decrease under the influence of the scientific criticism which is strengthening agnosticism in the other direction. On one side we have no belief, and on the other a belief in spiritual agencies which equals, if it does not exceed, such faith during any past period of modern history. Men and especially women of intelligence and cultivation are unquestioning in their reliance in the faith cure and the prayer cure, and the movement to create the anomaly of a spiritual science receives ardent support from thousands of people who take much pride in their reasoning faculties.”

Wendell used the February 1892 commemoration of the Salem witch trials to step into the affray and, by using the trials by way of comparison, to clarify the real meaning of occultism.[3]

Wendell’s study of Cotton Mather pushed him to reconsider the witch trials and brought him to a startling conclusion: “I am disposed to believe not only that in 1692 there was existent in New England, under the name of witchcraft, a state of things quite as dangerous as any epidemic of crime, but also that there is, perhaps, reason to doubt whether all the victims of the witch trials were innocent.” He then observed three popular types of contemporary occultism – materialization, trance-mediumship, and automatic writing – to understand Salem in a new light and “to dissent from the rationalistic view of the tragedy of two centuries ago.” Materialization struck him as “an indubitable fraud.”

A group sat in total darkness and was whipped into hysteria by organ music and “uncanny shapes” that appeared around the room to interact with participants. “You could not see how the trick was done, but the trick was essentially like what any number of travelling magicians perform,” he recalled. The materialization method also prayed on the melancholic. In one case, a distraught father claimed to have embraced his dead son, recently deceased from suicide. Yet, while it was a fraud and the mediums genuine “knaves and charlatans,” they also appeared to believe what they practiced was true, like “some mysterious subjective experience that had to them a semblance of fact.” Wendell believed the entire experience debased its joiners and he heartily agreed with a friend, who told him, “he had no shadow of doubt that if they were spirits they were devils.”[4]

Trance-mediums channeled the dead and mentioned names and facts told to them by the departed. The one Wendell visited seemed like a perfectly good person, he reported, mentioned some facts pertaining to his life, and “in a vague kind of way, she seemed to follow my line of thought.” It looked like mind reading. At the session’s conclusion, she began to spasm and fit, grasped his knees, and begged him not to let the spirit take her away. A jarred Wendell declared, “You would have said she saw the Devil himself waiting for her.” Despite the frightening performance, he believed her to be an honest woman, who had fallen into “a very abnormal state, honestly self-deceived; and in this abnormal display and in this self-deception was a quality of debasement, more subtle, less tangible, than I had found in materialization, but, if you granted the supernatural hypothesis at all, equally diabolical.”[5]

Finally, Wendell tested automatic writing in private, when he found himself doodling and scrawling lines without any willful guidance. After a time, the lines finally presented themselves, amusingly, in the composition of one word: “sherry.” He soon ceased these writing experiments, saying they “left me in an irritable nervous condition for which I can find no better name than demoralized . . . will, intelligence, self-control, temper, were alike inferior things after the experiments to what they had been before . . . the further I got in my very slight excursion into occult experience, the further I was from intelligence, veracity, and honesty.” Considered together, the three occult practices combined into a kind of “mental or moral disorder,” materialization being the worse, an “elaborately dishonest mummery.” It was a series of practices that led normally honest people into debasement and fraud.[6]

Fresh off his Mather biography, this occultism felt oddly familiar to Wendell. He read Charles Wentworth Upham’s books on Salem witchcraft, as well as the trial evidence, and was stunned about how witchcraft hysteria looked so current. “[T]he controlling spirit, the atmosphere of this grotesque tragedy was something I had known in the flesh.” His experience of materialization mirrored charges made in 1692: “There is fraud in both, terribly tragic fraud then, grotesquely comic fraud now, but in both the fraud is of the same horrible vaporous kind; and in both there is room for a growing doubt whether there be not in all this more than fraud and worse.” True, the Salem court convicted people on “worthless” spectral evidence and when it was condemned as unreliable, the trials ended. Spectral evidence rebounded “against the witnesses themselves.” Clearly, however, there was hypnotism or self-hypnotism afoot amongst the young women of Salem drawn into a state of delirium. Wendell detected a likeness between the convulsing trance medium and the Salem accusers. The medium almost certainly hypnotized herself – isn’t it conceivable Salem women did the same?[7]

Wendell also drew from Christian Science, which he disliked, the belief that concentration of the mind could have physical effects. Accused Salem witches stuck pins in a doll (or “poppet”) to hurt people, and in so doing focused their attention on a victim and believed they could harm him in a tangible way. Wendell believed this demonstrated the methods prevalent in 1692 were alive in his own time. “[H]ow much more credible witchcraft is than it used to be, now that we see these honest, intelligent mystics all about us”:

“I have neither the scientific nor the historical learning necessary to make anything I should say more than suggestive to better and wiser students. But this evidence, typical of much more that can be dug out of those bewildering old documents, will show you the sort of thing that has led me both to believe that there was abroad in 1692 an evil quite as dangerous as any still recognized crime, and to wonder whether some of the witches, in spite of the weakness and falsity of the evidence that hanged them, may not after all have deserved their hanging.Some citizens of Salem did indeed engage in “unholy experiments.”[8]

What happened when mediums and their Salem progenitors fell into a hypnotic state? The answer lay with evolutionary science, a consistent theme in Wendell’s speeches and books. Predestination and the idea of an elect represented Puritan insights into natural selection centuries before Darwin, he believed. Wendell proposed that our human ancestors might have had “certain powers of perception which countless centuries of disuse have made so rudimentary that in our normal condition we are not conscious of them.” In the medium’s fanciful spasms, it was not unreasonable to believe those older characteristics found their way back into current consciousness. These revivified human conditions had two qualities.

First, since they existed when pre-social man lived in a Hobbesian hell, “we should expect them to be intimately connected with a state of emotion that ignores moral sense.” Second, they also predated the use of “articulate language,” thus we should expect these conditions to manifest in non-verbal ways beyond the description of language. This is at least partially why we perceive occultism as nonsense. Mediums and witches may apprehend things others cannot, but “they perceive them only at a sacrifice of their higher faculties mental and moral not inaptly symbolized in the old tales of those who sell their souls.” Hence for Wendell, the Salem witchcraft trials were a sign of genuine evil, not necessarily for the executions, but the willingness of some in seventeenth century New England to, if you will, sell their souls.

“If this be true, such an epidemic of witchcraft as came to New England in 1692 is as diabolical a fact as human beings can know; unchecked, it can really work mischief unspeakable. For unchecked it would mean that more and more human beings would give themselves up to deliberate, or perhaps instinctive, effort to retrace the steps by which human intelligence, in countless centuries, has slowly risen from the primitive consciousness of the brute creation.”

The real witches were just as often the accuser as the accused. Through self-hypnosis, they reached into this pre-rational evolutionary past and accused others of witchcraft to cover their own guilt.[9]

To answer the question of why otherwise pious New Englanders would turn to self-hypnosis, Wendell pointed to the rigor of Puritanism. Witchcraft emerged out of the intense introspection required by the Puritan creed to discover whether believers were one of the “saints,” God’s elect. Imagine the anguish hanging over desperately searching Puritans, who were unable to discern salvation, and in distress dabbled in the occult and hypnotism as a source of power and meaning. They turned to the devilish arts after failing the seventeenth century “survival of the fittest.” God had not chosen them. Was this not akin to melancholic Americans in the late nineteenth century, searching for meaning in a frenetic materialist democratic world where God was dead and everyone competed to be among the fittest?

“In a world dominated by a creed at once so despairing and so mystic, it would not have been strange if now and then wretched men, finding in their endless introspection no sign of the divine marks of grace, and stimulated in their mysticism beyond modern conception by the churches that claimed and imposed an authority almost unsurpassed in history, had been tempted to seek, in premature alliance with the powers of evil, at least some semblance of the freedom that their inexorable God had denied them. It was such an alliance with which the Salem witches were charged. It is just such miserable debasement of humanity as should follow such an alliance that pervades the evidence of the witch-trials, just as to-day it pervades the purlieus of those who give themselves up to occultism in its lower forms.”

The fate of the hanged witches, though established with spurious evidence, was their “moral due”[10]

The trials blunted American interest in occultism for more than a century. Had they not, Wendell believed it would have “demoralized our national character” in the eighteenth century age of revolution and independence. By 1892, it had returned, and while he never called for a new round of trials (based on something less spectral, like evolutionary science), he hoped sunlight on fiendish occult practices would condemn them to the shadows for another two centuries. The new condemnation would come, not from Judge John Hathorne or Cotton Mather, but from Charles Darwin and a Harvard English professor.[11]

Notes

[1] Boston Evening Transcript, March 1, 1892.

[2] Michael J. Connolly, “Barrett Wendell: New England Orderly Idealist,” Modern Age 48, no. 4 (Fall 2006): 320-323.

[3] New York Sun, March 25, 1889.

[4] Barrett Wendell, “Were the Salem Witches Guiltless?” in Stelligeri, and other essays concerning America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1893), 66-69.; Parts of Wendell’s 1892 speech were taken directly from his Cotton Mather biography of the previous year.

[5] Ibid, 69-71.

[6] Ibid, 71-73.

[7] Ibid, 74, 76-80, 86-87.

[8] Ibid, 81-83.

[9] Ibid, 83-86; Connolly, “Wendell,” 326-327.

[10] Wendell, “Witches,” 75-76, 87-88.

[11] Ibid, 89.