A Voegelin Literary Criticism

Voegelinian literary criticism is still taking its first steps.

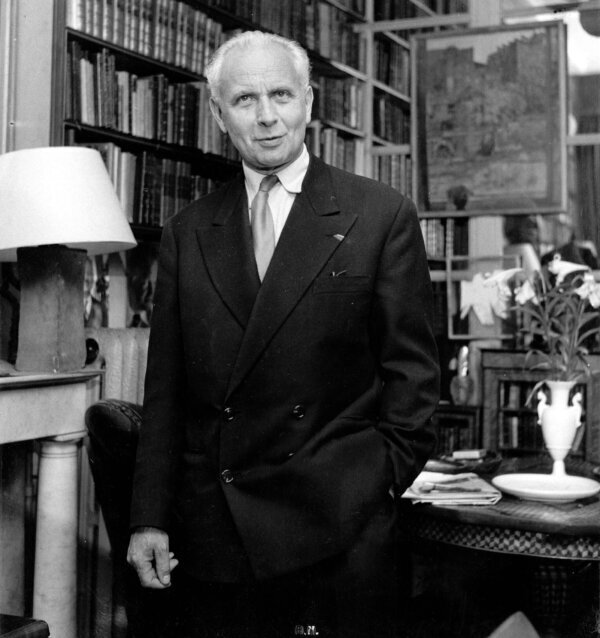

Voegelin himself was a master critic of the philosophical text and — he wrote in a letter to Robert Heilman — an amateur critic of the poem, play and novel. Voegelin practiced literary criticism most assiduously in his discussion of Homer and the Athenian tragedians in The World of the Polis and in his analysis of the Henry James novel The Turn of the Screw in a 1971 issue of The Southern Review.

As early as 1967, an article by Anselm Atkins in Drama Survey, “Voegelin and the Decline of Tragedy,” worked to insert the philosopher into literary criticism. Since then, Voegelinian literary criticism has moved ahead fitfully with the most concerted efforts being made by Glenn Hughes in his work on Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot and Emily Dickinson, and by Charles Embry in The Philosopher and the Storyteller (2008), the first monograph to use Voegelin’s later philosophical vocabulary as critical tools in an analysis of novels from England, Germany and the United States.

A Voegelinian literary critic has to hold three bodies of texts in his mind: his author’s or authors’ poems and stories, Voegelin’s books and essays, and other texts of Voegelinian literary criticism. The current model in Voegelinian literary criticism seems to me to tilt toward the wrong side of the divide in that it scolds authors for not getting right their personal symbolization of the Ground of Being in relation to some “correct” interpretation, whatever that might be.

One of the tropes of this criticism has been to find spiritual illness, pneumopathologies, attachment to Second Realities, in the poems and stories being studied. Reflecting on a Voegelinian essay I wrote on Elizabeth Bishop that is completely in this line, I have begun to question if Voegelinian literary criticism will get anywhere if it continues to apply the “this author is spiritually unwell for this reason” template.

A Voegelin-as-harridan scolding poets who are insufficiently or not “correctly” attuned to the transcendent is not going to convince anybody in literary studies of his utility. The desire to find what’s wrong with an author’s inner symbolization of the Ground of Being is an attitude we could pick up from reading Voegelin. The Voegelin that is being used is “the Cold War, anti-Gnostic Voegelin,” and I believe that Voegelin has less to offer literary theory than “the philosopher Voegelin.” In other words I think a literary criticism inspired by Voegelin has to pass from the present judging phase to a descriptive phase, mostly using terms from Voegelin’s last period as a starting point.

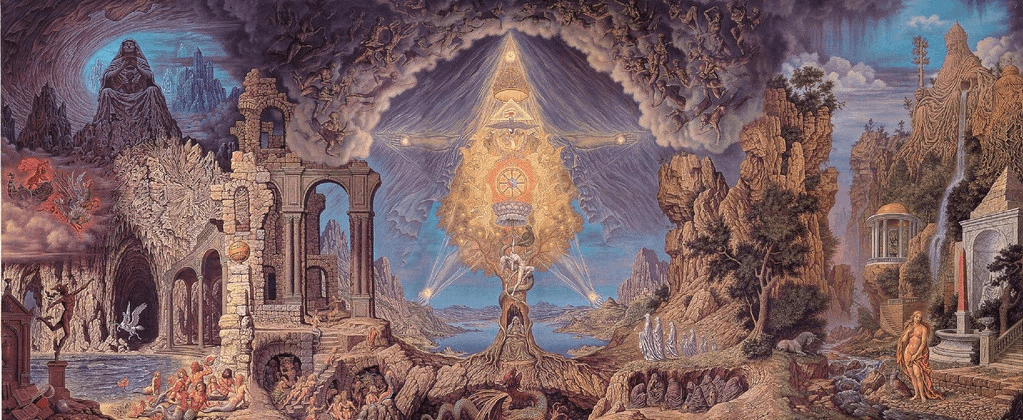

The descriptive Voegelinian criticism that I am proposing would work toward normalizing terms like “the It-reality” (from In Search of Order) and “the Question” (from The Ecumenic Age) in literary studies. How does this novelist express the It-ness and thingness of reality? How does this playwright formulate the Question? How does this poet create an envelope of myths that makes possible, after his death, the creation of a practical government for a long-oppressed people? These are the kinds of Voeglinian questions that might infiltrate literary studies.

We are well aware that twentieth-century literary theories from Northrop Frye’s myth criticism to the Edward Said inspired post-colonialism illuminate for the reader some mystery previously unseen in the text. All of them are both useful and useless: useful in that they shake up passive first readings and useless in that for certain of their practitioners they become a Rosetta stone that explains a text once and for all. A Voegelinian criticism is as susceptible as any other to such misuse.

One must also keep in mind that students of literature are serially inspired by popular philosophers, but not being in the field themselves tend to follow two steps behind the initiated. Hence, a Heidegger, Foucault, or Levinas have their moment in literary theory, leave a mark, and are then absorbed into the critical discourse. Voegelin’s moment of absorption is still in the future.

The temptation to give authors grades based on their spiritual health might be made in passing, but if such grade giving continues as the dominant motif of Voegelinian criticism that criticism may never become an important influence in literary studies. In the twenty-first century Voegelin will take on new forms. Voegelin as an analyst of religions — political, personal, and mythic — will still be useful as Nazism and Communism morph and take on new names. In literary criticism, he can be most valuable if understood as a Virgil leading the critic to more accurately articulated questions concerning the nature of reality and being.