Beyond Power and Will

Then every thing includes itself in power,

Power into will, will into appetite;

And appetite, a universal wolf,

So doubly seconded with will and power,

Must make perforce a universal prey,

And last eat up himself.

– Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, Act 1, Scene 3[i]

Living in the era of the Tudors, Shakespeare knew a thing or two about power, will and appetite. It can be a deadly combination which leaves a string of corpses in its wake. And like some alien creature in a horror B-movie it ends up eating itself. It’s almost uncanny that in a few lines the Bard could foresee one of the dominant motifs of modernity’s path to self-destruction: the lust for power of a Napoleon, the insatiable appetite of a Marquis de Sade, the deranged will of a Hitler. And yet, somehow, we haven’t gone over the abyss. What is it that has kept us in check? We have to be thankful that something else has been in play. That something else has its representative figures: Shakespeare himself with his capacity to diagnose the malady of unbridled power; Dostoevsky who opposes willfulness with humble love; Solzhenitsyn who stands up for truth no matter the cost; Etty Hillesum who proclaims the beauty of creation in the midst of the horror of a concentration camp. Martin Buber who reminds us of the sanctity of every Thou.

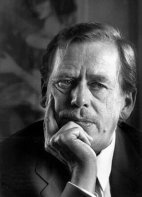

And yet, the abyss hasn’t gone away. Power, will and appetite are still a deadly force. Perhaps what’s required is that all of us become representative figures. Of what exactly? In a speech given in Philadelphia on July 4th 1994, Vaclav Havel outlined what he sees as the essential need of our times if we are to avoid catastrophic conflict. The two great achievements of modernity are the discovery of the scientific method and respect for the rights of the individual. And yet, according to Havel, our postmodern condition has shown up the limits of what we have achieved. With our rationality and our sense of justice we have given to ourselves the position of supreme beings in the universe. That means an eclipse of any form of transcendent reality which could ground our ultimate meaning and purpose. We are not subservient to anything but what we tell ourselves. But that sounds suspiciously likely whistling in the graveyard to convince myself I’m not afraid. Western democracies pride themselves on their espousal of human rights, but with what legitimacy? If our scientific worldview reduces all living beings to “selfish genes” struggling for survival, why should I respect your right to exist if it impinges on my freedom to live as I please?

Havel advances what he acknowledges to be a “provocative” argument. Namely, that we de-throne ourselves as masters of the universe, and find a new transcendent ground for our search for the true and the good. This means recovering, “the awareness of our being anchored in the earth and the universe, the awareness that we are not here alone nor for ourselves alone, but that we are an integral part of higher, mysterious entities against whom it is not advisable to blaspheme.”[ii]

Only in this way can we hope to save ourselves:

“Yes, the only real hope of people today is probably a renewal of our certainty that we are rooted in the earth and, at the same time, in the cosmos. This awareness endows us with the capacity for self-transcendence. Politicians at international forums may reiterate a thousand times that the basis of the new world order must be universal respects for human rights, but it will mean nothing as long as this imperative does not derive from the respect of the miracle of Being, the miracle of the universe, the miracle of nature, the miracle of our own existence. Only someone who submits to the authority of the universal order and of creation, who values the right to be a part of it and a participant in it, can genuinely value himself and his neighbors, and thus honor their rights as well.”[iii]

But can a turn towards the transcendent really save us? In his talk, Havel alludes to Heidegger’s “only a God can save us now”, but the tone of Heidegger’s comment seems to tend more towards despair than hope. Perhaps a crucial element in what Havel is calling for is that he is not proposing another ideology. The history of the twentieth century has tragically demonstrated their murderous futility. Instead, he is calling for personal conversion.

Self-transcendence or openness to the divine ground is a radically personal choice. No one can do it for you. And unlike an ideology it is rooted in reality. So much so, that in different but equivalent forms, it can be found in all the great religious traditions. Yes, Huntington warned us about a coming clash of civilizations. But when we look at concrete cases of actual violent conflict that are taking place in the world today whether it’s Kashmir or the Congo, Syria or Sudan, what we are witnessing are not just disputes between civilizations. They are also age-old, raw and bloody expressions of power and will. None of this is going away soon, but we can have reason to hope in the seeds of the true, the good and the beautiful that can be found in every culture. That means there is a space for dialogue and the mutual exchange of patrimonies. By transcending our differences and accessing our uniquely human capacity to embrace what is other than ourselves, we can live harmoniously in a common world. This is what Havel is counting on:

It logically follows that, in today’s multicultural world, the truly reliable path to coexistence, to peaceful coexistence and creative cooperation, must start from what is at the root of all cultures and what lies infinitely deeper in human hearts and minds than political opinion, convictions, antipathies, or sympathies – it must be rooted in self-transcendence:

1. Transcendence as a hand reached out to those close to us, to foreigners, to the human community, to all living creatures, to nature, to the universe.

2. Transcendence as a deeply and joyously experienced need to be in harmony even with what we ourselves are not, what we do not understand, what seems distant from us in time and space, but with which we are nevertheless mysteriously linked because, together with us, all this constitutes a single world.

3. Transcendence as the only real alternative to extinction.[iv]

Notes

[i] http://shakespeare.mit.edu/troilus_cressida/full.html.

[ii] Vaclav Havel, “The Need for Transcendence in the Postmodern World”, Independence Hall, Philadelphia, July 4, 1994, http://www.worldtrans.org/whole/havelspeech.html.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.