Contra Gopnik

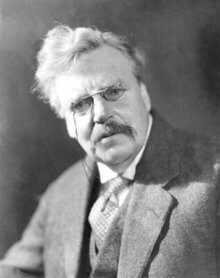

In the 7th of July 2008 issue of the New Yorker , Mr. Adam Gopnik published “The Back of the World” (G.K. Chesterton’s ‘The Man who was Thursday’) and Chestertonians are still sore as a gumboil.

What that has to do with Voegelin? A good deal, I think, but first let’s look at the article, or a bit of it.

By the way, although the whole article is only available on the New Yorker site to those who register, you may already have access. Many Public Libraries offer databases of magazine articles; these may be reached from your home computer with the use of that most valuable civilization tool the Library Card. Ask your local branch.

Mr. Gopnik (a charming writer in other circumstances) makes three charges:

- Chesterton is an anti-Semite.

- Chesterton is a benighted reactionary.

- Chesterton as a stylist is oldfashioned and icky.

The first charge has been chewed over through the years and we won’t go into it except to say that it is plausible bosh.

We will also pass the second point which is manifest bosh.

Point three is the kicker. This will require a longish quote.

” . . . There are two great tectonic shifts in English writing. One occurs in the early eighteenth century, when Addison and Steele begin The Spectator and the stop-and-start Elizabethan-Stuart prose becomes the smooth, Latinate, elegantly wrought ironic style that dominated English writing for two centuries. Gibbon made it sly and ornate; Johnson gave it sinew and muscle; Dickens mocked it at elaborate comic length. But the style–formal address, long windups, balance sought for and achieved–was still a sort of default, the voice in which leader pages more or less wrote themselves.”

“The second big shift occurred just after the First World War, when, under American and Irish pressure, and thanks to the French (Flaubert doing his work through early Joyce and Hemingway), a new form of aerodynamic prose came into being. The new style could be as limpid as Waugh or as blunt as Orwell or as funny as White and Benchley, but it dethroned the old orotundity as surely as Addison had killed off the old asymmetry. Chestertonian mannerisms–beginning sentences with “I wish to conclude” or “I should say, therefore” or “Moreover,” using the first person plural un-self-consciously (“What we have to ask ourselves . . .”), making sure that every sentence was crafted like a sword and loaded like a cannon–appeared to have come from some other universe.”

“Writers like Shaw and Chesterton depended on a kind of comic and complicit hyperbole: every statement is an overstatement, and understood as such by readers. The new style prized understatement, to be filled in by the reader. What had seemed charming and obviously theatrical twenty years before now could sound like puff and noise. Human nature didn’t change in 1910, but English writing did. (For Virginia Woolf, they were the same thing.) The few writers of the nineties who were still writing a couple of decades later were as dazed as the last dinosaurs, post-comet. They didn’t know what had hit them, and went on roaring anyway.”

This is, I believe, the real center of Gopnik’s attack, for the first two points we may argue, but the third point, presents itself as a matter of taste, and therefore closed to criticism.

After all, those who are of the proper party (people like us) will agree.

Those who disagree, well, perhaps they should seek help, like Lassie in the cartoon.

There was indeed a change in style, and Mr. Gopnik describes it reasonably well.

But behind the change in style, is a deep level change in habits of thought.

Anyone who has read a good deal recognizes the old way. We learned it in Latin class. But behind the old rhetorical machinery, with its points of fact, explicit deductions, etc. etc. is a hidden assumption: man has a duty to consent to reason.

This assumption has operated from Homer on: if an argument is convincing, you are supposed to admit its validity, and act on it.

The assumption of the new style is : what is real is your desire . It works on suggestion, implication, implicit understanding between reader and writer. It is thoroughly private. It is arational.

The new way and the old must be at war because they disagree about what man is.

The old style makes his essential characteristic reason.

The modern way, locates his nature in conscious desire.

The old way works from a shared vision of facts.

The new way operates from psychological science and control.

The one is the language of politics, the other of advertising.

That such a writer as Chesterton should be popular must be intolerable.

And Voegelin?

If the influence of Voegelin does grow to the point where it troubles the counsels of the brightest and best connected, the counterattack may come in a shape that resembles Gopnik’s approach, though not the same.

It will be difficult to argue Anti-semitism, but Ant-feminism will serve.

Pointing out the dangers of modernism will be evidence of a desire to bring back the Kaiser.

But the real front will be opened up on a charge of obscurity and turgid style, and it will mask the real charge: Voegelin is reasonable, and that he demands that the reader be reasonable too.

That is unacceptable.