Determinism and the Good Life Are Incompatible

This article is a continuation of an interaction with a blogger calling himself Robot Philosopher. RP is a polemicist and likes to pepper his arguments with snide comments directed at me personally. Since these asides add nothing to the debate and are simply ad hominem, I have removed them. Determinists are forced into their untenable and reflexively self-contradictory positions by their assumption of materialism and a belief in a mechanical universe. In engaging in argument on this topic at all, agency is implicitly assumed by the determinist both on the part of the person doing the (not so) rational persuading and on the part of the person who is supposed to be rationally persuaded, in direct violation of the determinist’s beliefs. Without agency, at best the determinist is simply a machine following its programming, as RP happily and continually asserts, with no ability to assess the value of his arguments or to change them if they are deficient. According to the tenets of a determinist, he has no choice but to believe what he believes and thus is behaving identically to a mindless machine. And then the “person” he is persuading, from his point of view, likewise follows its programming and is being buffeted by mechanical and physical processes from which he is metaphysically indistinguishable. Without agency there are only “sequences of events” and no one is arguing with anyone and persuasion is an illusion. Many physicists seem to be determinists. This failure of logic on their part – in fact – rejection of the existence of logic as a causally efficacious meaningful thing, hopefully is not reflected in their physics. If it is not, then at least their physics has value. When philosophers adopt determinism, and free will and determinism are a decidedly philosophical topic, they have failed at the only thing they are supposed to be doing; philosophy. More shame on them. It might not matter if physicists are bad philosophers, but it matters if philosophers are bad philosophers!

Paragraphs in quotation marks are quotations from me to which RP is responding. And anything bullet-pointed is my reply to RP’s criticisms. The argument continues with a quotation from me:

“What on earth would “a good life” mean for a mindless automaton with no free will? Or, if it has a mind, a mind that is trapped within the automaton with no ability to alter a single thing about its life?”

Again, experience matters. Whether or not we make actual choices, we still experience good or bad. We didn’t decide what we experience as good or bad, but we still DO experience.

Iain McGilchrist in The Matter With Things[1] points to studies concerning the negative effects of believing in determinism. They involve an increase in antisocial attitudes and behaviors, increases in deceitfulness, aggressive behavior, selfishness, lower achievement levels and increased susceptibility to addiction.[2] In other words, determinism predictably gives rise to antisocial fatalistic nihilism, contrary to RP’s assertions. Lower achievement levels seem obvious, since why make an effort if the outcome is predetermined? A belief in determinism is inherently disempowering and counterproductive, as any fatalistic attitude will be.

What makes a good life good is a far-reaching topic. Some suggestions from the past are that a good life is a flourishing life where we realize our human potential. We develop friendships, engage in self-chosen projects, make mistakes, learn from those mistakes and act differently next time, and we fall in love and have children. Without agency, none of those things are possible. If I decide to cultivate someone as a friend, it is important to me that it is me making that decision and also that their friendship is voluntary. If it is compelled and, for instance, someone is forcing them to be friendly, or perhaps bribing them to spend time with me, then that would ruin what was good about any of it. Determinism means all human thoughts and actions are regarded as compelled.

If determinism is true, I cannot actually do If consciousness and thus experience is supposed to exist, then not only must I be completely passive with regard to the world, under determinism, even how I react to these experiences has been determined by something else.

Imagine there is someone you love. I, for instance, love my son. If I had the choice (a real one) between him dying or him living in a deterministic universe, I would prefer that he die. I would have to say to him, “Look, Nick. Your consciousness can continue on but not in any way that you are currently familiar with. It will be completely passive. It will be a kind of bare awareness. You will lack all agency. Someone or something else will make every single decision about every single aspect of your life, from the most trivial to the most important. You will not get to choose who you will date, or whether you will have sex with that person either. Should you have sex, it will effectively be rape, both on your part and the person you are having sex with since the consent of either party is meaningless in this context.[3] You cannot decide on your job, or your friends, or whether to play a musical instrument, or to look at a sunset. Not even whether to, or when, to brush your teeth. No element of your existence will be too trivial for someone or something else to decide for you. Prisoners in jail will have infinitely more freedom than you ever will. But it gets worse…

Stoicism, particularly the kind espoused by Epictetus, is an extraordinarily passive philosophy but it still has more truth to it than determinism. Epictetus had been a slave, though he was later freed. As a slave, he needed to find a way of coping with a life he had no control over. He suggested treating life as though one were playacting, interestingly, in the manner of schizophrenics who feel this way spontaneously. Epictetus wrote that if one finds that one is poor, short, and ugly, one should be the best poor, short, and ugly person one can be. Good actors are only too happy to stick on an ugly nose and play the role they have been assigned. The trouble with this view of things is that it is too passive. The Serenity Prayer says, “O God and Heavenly Father, Grant to us the serenity of mind to accept that which cannot be changed; courage to change that which can be changed, and wisdom to know the difference, through Jesus Christ our Lord, Amen.” The prayer distinguishes between things we cannot change and things we can. Epictetus does not. He treats all things as things he has no control over, presumably as an adaptation to living a life of slavery. Most of us are not slaves, so this attitude would be foolish.

But, the one thing we can change, and thus have agency over, is how we respond to life experiences and Epictetus has some very interesting and profound things to say on that topic. He suggests, for instance, that if someone calls you insulting names, you should respond in a positive manner and never get annoyed. If the insults are false, one can merely point out that they are false, but you could say, “that is not true, but I have other defects you have not mentioned yet,” and then list some. If the insults are true, one should simply own up to them. How can someone saying something true about you harm you? If you are male and 5’4” tall and someone calls you short they have not harmed you. If you are 6’4” and someone calls you short, you can simply point out that they are mistaken. If you find yourself getting annoyed, then this person has identified a wound, a sensitive spot, in you and you should thank them for providing this educational experience.

Under determinism, the level of passivity reaches its maximum. Not only can you not decide anything at all about how to live your life and who to befriend, but you cannot even choose how you react to anything. You cannot follow Epictetus’ advice about how to respond to insults because you cannot do You are a mannequin, a marionette, with something akin to a photoreceptor cell attached recording experiences.

Imagine you take a date out for a meal and you find her enchanting, delightful and interesting. Under determinism, none of that has any meaning. You did not choose to take her out, and there is no real “you” finding her enchanting. The latter point is complicated because as with preferences, perhaps only a relatively small part of finding someone charming is voluntary, but as Winstonscrooge says, we only need that small part for free will. Regardless, your response to your date has nothing to do with you per se, but is merely part of a chain of causation.

Under determinism, you could be taking Miss Piggy from the Muppets out, not because you wanted to, and deterministic forces will make you feel her to be the most wonderful person you have ever met; or not.

The life of an automaton with no ability to alter a single thing would be hell on earth. Euthanasia for such an entity would be the greatest kindness.

Under determinism, our metaphorical programming decided what the experience would be. Then our “programming” decided what “we” would think about that experience. The “we” of course being effectively a bunch of circuits indistinguishable from a robot.

We can quite easily make a program with machine learning, these days. In such programs, we provide a reward for achieving tasks we wish them to achieve, which reinforces the behaviors the code performed. If they fail, there is either a “punishment” or no change – I forget.

The use of the term “reward” in this context must be metaphorical to the highest degree possible. “Reward” is an essentially mind-dependent phenomenon involving incentives. I’ll come back to this shortly.

Cognitive scientist Gary Marcus points out that what is described as A.I. mostly involves “look up tables.” If the answer cannot be found there then, since the machine cannot reason, it is stuck. If, for instance, you saw a man carrying a stop sign and you had never seen that before, you would probably know how to respond to that novel situation, but a computer would not. Marcus comments that driverless cars are supposed to be on the horizon because, after forty or fifty year’s work, scientists can now get cars to stick to their lanes. “We’re almost there,” they say. But, Marcus comments, a ladder to the moon will never get you to the moon. You can get a little bit better driverless car, or a program for detecting sarcasm, so they can seem good in a directional way, but really, you are no closer to your actual destination. With regard to A.I., Marcus compares the situation to climbing K2 when you really want to climb Everest. The only way to get up Everest is to go back down K2 and start again. Since, as I will explain below, A.I. as it currently exists lacks any understanding of what it encounters, it will never get there. At the core of the problem, since intelligence cannot be reduced to algorithms, writing more algorithms will never get you to where you want to go, no matter how clever and sophisticated. Large language models, for instance, are “autocomplete on steroids” says Marcus. They are predicting the next words in sentences, but it is just not the right solution. K2 not Everest. You ask, “What do you like to do in your spare time?” And the AI says, “I like to spend time with friends and family.” It has just found those words in its database, but has no idea what “friends” or “family” means. If you ask it, it will just assemble some words from its database again. Since we do not know how a child learns language, how it connects, for instance, the concepts “go” and “went” and thus understands the concept of time, we cannot get a machine to do it.

This video, How Machines Learn, was sent to me by my computer programming son. Algorithms determine what YouTube videos will be suggested to you. In the old days, we gave bots instructions that humans could explain. But many things are just too big and complicated for humans to program. Out of all the financial transactions going on, which are fraudulent? Of the octillion videos that exist, which eight should the bot recommend? Also, related to the comment above, we do not know how people and even little children learn to distinguish a 3 from a bee. So, we build a bot that builds bots and one that teaches them. Builder bot assembles more or less at random. And teacher bot cannot tell a bee from a 3 either. If it could, we would just use teacher bot. The human gives teacher bot millions of pictures of 3s and bees and an answer key (look up tables) as to which is which. Teacher bot tests student bots. The good ones are put to one side. The bad ones discarded, as judged by the answer key. Builder bot is still not good at building bots, but now it takes the remaining bots and copies them while making changes and new combinations. The teacher has thousands of students and the test involves millions of questions. As the student bots improve, the grade needed to survive to the next round gets higher. Eventually, the bot is pretty good. But, neither the builder bot, teacher bot, the human nor the student bot itself knows how the bot is doing what it is doing. The student bot is only good at the types of questions it has been taught. It is great with photos, but cannot handle videos and is baffled if the photos are upside down. And that’s the problem. Humans can easily handle something upside down, and something it has never encountered along those lines, but where humans have not anticipated a particular scenario, the bot will likely not be able to make up for the deficient training by improvising. No complete set of rules can be written for driving situations, just as the workers at the front desk of a hotel cannot be given written instructions covering all eventualities. They need discretion to be able to do their jobs well. Concerning the bot, things that are obviously not bees, it is confident that they are. All the teacher can do is include more questions to include the ones that the student bot gets wrong. More data = longer tests = better bots. The human directs teacher bot how to score the test.

The student bot has no idea how it does what it does. The same could be said about humans, in many instances. We do not know how we distinguish bees from threes. However, the goal-directed nature of machine learning is determined by humans and the test questions are also determined by humans. Thus, machine learning does not involve understanding or teleology. It is dependent/parasitic on human understanding and human teleology. Machine learning is a mere tool for us. It can mimic some human abilities to a limited degree, while remaining completely dependent on humans to function. It is climbing K2, not Everest. At no point can machine learning become self-driven and self-assessing because it is not heading in that direction. Real interesting learning by humans has no predetermined outcome. Real advances in human knowledge are adventures into the unknown. And these are made by the auto-didact, perhaps after a formal education. Einstein or Max Planck have to have “a-ha” moments that involve actual novel insight into the structure of physical reality, which is not something a computer can do because there is no algorithm, no full-proof written instructions, into how to penetrate deeper into the nature of physical reality than ever before.

On the philosophical significance of machine learning, the following is from A.I. and the Dehumanization of Man:

Following algorithms does not require real understanding. The instructions are provided by the programmer and the machine does what it is told. The phrase “machine-learning,” however, sounds like some way out of this dictatorship of the programmer.[4]

With bottom up algorithms, a procedure is laid down for the machine to “learn from experience.” The system must be run many times, performing its actions on a continuing input of data with the rules of operations being continually modified in response.

The goal of this “learning” has been clearly set in advance, e.g., to identify a person’s face, or a species of animal, or to diagnose cancer from an X-ray. After each iteration, an assessment is made and the system is modified with a view to improving the quality of the output. This assessment requires that the correct answer is known beforehand.

But “the way in which the system modifies its procedure is itself provided by something purely computational specified ahead of time.”[5] This is why the system can be implemented on an ordinary computer. In real human learning from experience, no one knows what he will learn in advance. Nobody would call being told beforehand what the right thing to think was “learning from experience.” That would be learning from someone else. And then when it is added that exactly how you will use data to reach this foregone conclusion is also determined by someone else, this resembles learning by rote. Real learning from experience, has no goal known in advance, nor is it set in stone how learning will take place. The phrase “machine learning” sounds like the machine will be learning by itself, and reaching its own conclusions. It is not. Neither the conclusion, nor how the conclusion will be reached, is self-determined. Real learning from experience is very interesting because no one knows what conclusions experience will teach. That is why it would be fascinating to consult one’s eighty-five year old self about many topics because no one knows what life lessons will have been learned by that point in one’s life.

Penrose writes that the key distinguishing feature of bottom up programming as opposed to top down is that “the computational procedure must contain a memory of its previous performance (‘experience’), so that this memory can be incorporated into its subsequent computational actions.”[6] It should be noted that mistakes and machine learning are inextricably interlocked. Without “mistakes” the system could not function. It is only with top down programming that computers have significantly outperformed humans such as numerical calculation or calculating games like chess.

Machine learning does not really change anything and neither does parallel versus serial processing. Whether computational actions are performed one at a time or a task is divided into sections and the sections are tackled simultaneously makes no philosophical difference.

Roger Penrose provides a pithy summary of why artificial “intelligence” is a misnomer. There is no intelligence without understanding, and understanding requires awareness.[7] An operational definition of “understanding” is not sufficient because, for instance, a mathematical algorithm can be followed with or without understanding. Only the person who understands would be able to formulate a new algorithm for achieving the same task since the person in the dark does not even know the purpose of the algorithm.

Computer programs, as products of human intelligence, can thus appear to be intelligent themselves. But effective computer simulations almost always are exploiting some significant human understanding of the underlying mathematical ideas. Computer algorithms that can differentiate knotted string from simple heaps depend on very complex and recently developed (twentieth century) geometric ideas – though a person can often test the string with simple manual manipulation or common sense.[8]

The concepts of reward and punishments do not make sense in a deterministic universe. These are yet more things a determinist is not allowed to have without contradicting his own metaphysics. Physical determinism involves cause and effect pushing from behind. A reward or punishment would resemble a goal in relevant ways. Goals exist in the future and pull us towards them, as do rewards, rather than being pushed from behind. It can be described as backwards causation. In the case of punishments, the goal would be to avoid getting punished. However, goals and purposes have been eliminated by modern science. At least, that has been an aim (goal!) of scientists. Their elimination is, in fact, a defining feature of what makes modern science modern. At best, goals and purposes are commonly regarded as placeholders until a fully mechanical explanation has become available.

Rewards and punishments depend on the existence of minds. Dog training typically involves rewards. Dogs have minds. But, for nonsentient entities, the concept of “reward” is simply inappropriate. You do not “reward” water for running down the drain the right way, or your car for a good performance. You do not “punish” hurricanes to deter them from destroying cities.

Talking about “reward” in the context of a computer algorithm as though the computer scientists are meaning anything like “reward” in human beings is misleading.

If you give someone a reward, you are giving them something that they want. Computer programs do not want anything. “Hey, computer. If you do what I want you to do, I will reward you with a memory upgrade. How would you like that? Now will you do what I want you to do?”

A likely response from a determinist is, “Well, human beings are just robots following their programming, so if reward does not apply to robots/computers, it does not apply to human beings either.” That logic would be correct. Either way the concept of “rewards” is eliminated as redundant and inaccurate.

Regardless, here is an example of your apparently enigmatic “good life” for a “mindless automaton”. Reward.

“Reward” is not a meaningful concept without minds and agency. It assumes that I have choice and that my behavior is goal driven, namely to earn a reward and that without that reward I will have made a different choice.

If minds are causally efficacious, then we have escaped from the confines of physical determinism.

The term “reward” in this context is a very odd metaphorical use of it. In humans, it indicates a good feeling, perhaps a smile, a dopamine hit. No such thing is happening in machine learning. Machines feel nothing.

If reward just means another manipulation of the automaton by its ruler and programmer then this is not a desirable thing. There is no “good life” for someone whose life is significantly worse than the most pathetic slave, since a slave’s thoughts and feelings, his experiences, are his own. In Brave New World, people are manipulated by pleasure and take a drug Soma whenever they start to feel down. No one thinks the life envisaged in Brave New World would be good or desirable.

What a “reward” might mean for machine learning and what it would mean for a human being cannot be plausibly compared.

In 1984, Winston Smith is tortured by fear to the extent that he supposedly learns to love what his torturers want him to love. This defeat of the human spirit at the end of the novel represents the worst of outcomes. Dying with dignity is at least admirable.

With that simple variable, I have solved your philosophy riddle, prof!

We humans experience the good life as a sufficient amount of reward, with a minimal amount of punishment.

A reward for what? Dogs, in training, are rewarded for their actions. What am I being rewarded for? The dog can think, “I’m a good dog.”

A reward has to be the reward for something. I have not done anything.

I have no choice in any of my behaviors, if determinism is true, thus I am not being rewarded for making good choices nor punished for making bad choices. None of this language has any legitimate referent in this context. A reward implies I could have done otherwise.

It does not matter that we didn’t choose what rewards would satisfy us or by how much. It does not matter if you think we shouldn’t possess a sense of self if this were true. It’s irrelevant.

I dispute those assertions with every fiber of my being.

I encourage anyone who thinks this to read Brave New World and 1984, and for the father of both, We by Yevgeny

We are separate entities that can experience reward, just like our basic A.I.’s can. And you would agree that (for now), A.I.’s do not have free will, yes?

I.s are not conscious and thus do not have free will. They also cannot experience rewards since they do not experience anything at all.

So, what is the reason that even in your world, where determinism does not exist, machines can act exactly how I’m contending the world works, and yet you deny this could possibly be the case with human experience as well?

I am not sure exactly what RP is referring to when he says, “machines can act exactly how I’m contending the world works.” Machine learning, for instance, is completely reliant on human intelligence and cannot be fully automated. This is related to the Halting Problem and our inability to completely formalize mathematics by turning it into symbol manipulation with no requirement that those symbols are understood as having any meaning. If math could be formalized, understanding would be redundant. Only then could machines do what humans can do.

David Chalmers imagines that there could be someone behaving just like him, but without consciousness. The fact is that there never has been such a person and, I would claim, there never can be. Machines are rule-following devices. You can have a rule only for things you can predict. We are unable to predict the future, so we are routinely faced with finding solutions to novel problems. Sometimes we succeed, sometimes we fail.

The difference between a conscious person and a machine becomes a matter of pain when dealing with computerized customer service devices. Almost always when I have bothered to call some company it involves a problem that the computer cannot solve. When the Amazon website asks why you are returning a product, the list of options is simply not long enough. They have not anticipated the reason for every return, and they could not do so. Computers have no common sense and they will not be able to improvise a solution that will please a human being in this context. Whereas humans can do this easily.

What specific rule would you cite here why robots regularly do exactly what you purport humans incapable of – which is follow their programming, without additional spooky Deepak Chopra woo woo magically providing us with free will?

RP does not seem to be making sense here. I have never disputed that machines can follow their programming.

Human beings do not literally have “programming” so they cannot follow it in the manner of computers.

Robots/computers cannot do what humans are capable of. They rely on humans to assign their goals and to assess their performance.

I accept that for free will to exist something spiritual must be introduced. That I also have never disputed. That is why free will cannot be proved. Arguing for determinism, however is a performative contradiction. Arguments exist to persuade. Persuasion does not exist for determinists. Persuasion operates on minds and reasons. If minds are independent of physical causation then determinism is false. If minds are nothing but physical processes then persuasion is nonsense. Only causation exists.

If the unprovable metaphysical position called “materialism” is true, and minds are causally inefficacious, then determinism is true.

Where do we gain free will? At what point? What variables? What did we freely choose that affects our decision making?

Buddhists posit the 10,000 things as emerging from Emptiness. Emptiness has an unstoppable creative impulse and takes something from the no-thing and creates. To do that, it takes something from itself and makes it into something that appears not to be itself. Emptiness is Form, Form is Emptiness.

We can tune into this creative impulse; we have it within ourselves too, and direct it in our chosen directions.

Jacob Boehme posits something similar: the Ungrund. The causeless cause. Meonic freedom. The non-ground of Being. It has the urge to create and creation requires freedom. Creation takes something unknown and makes it known. It cannot be an algorithm because following a set of instructions is not creative.

The idea is that God the Creator and Father emerges from the Ungrund since the Ungrund is the precondition for creation.

The Ungrund is a potentiality that manifests physical and other spiritual realities out of itself. Potentiality is the infinite, and infinitely bigger than mere actuality. All that exists is finite and limited, thus Ungrund does not exist. It precedes existence.

Human beings have a connection to this infinity within themselves allowing us to escape physical constraints and to tune into what is creating physical matter in the process. Matter emerges from mind. Mind is not an emergent phenomenon from complexly organized matter. The related concept of panpsychism is apparently becoming increasingly popular with many scientists.

From: Does the Concept of Metaphysical Freedom Make Sense?

“What proceeds from The Great Mystery must be causeless in order to be free – otherwise physical determinism is simply replaced by spiritual determinism. If creativity were explainable, it would no longer be creativity. Freedom too is inexplicable. And it is the postulate that is the precondition for postulating anything since only agents can postulate. Berdyaev uses the phrase “creative dogmatism” at one point in his writing. If ever there were a right moment for creative dogmatism, the postulate of Freedom is surely one of them.

Though the Ungrund is by definition The Great Mystery and unknowable, one way of thinking about it that could make it a little more imaginable, is to compare it to another dimension that you can reach into, like a wormhole. It is another dimension that you cannot see inside, but you can reach your hand in and pull something out. What you pull out will be related to you, and your desires, preferences, personality, knowledge, and life experiences. Einstein had to know a lot about physics and mathematics to generate the theory of relativity, and he had to have a great imagination. As a young teenager, he had read an encyclopedia that combined physics and biology and in it was the thought experiment of what it would look like to ride a beam of light. He never forgot this and it inspired thoughts that led to his breakthrough discovery, along with working in a patent office where clocks were being patented, getting him to think about time in a new way. What Einstein discovered was also related to his knowledge, desire to know, and life experience. When Beethoven composed music, he knew a lot about previous music, and also a great deal about music theory. His style of music reflected him, his personality, his cultural environment, and his preferences; and even the nature of his creative and imaginative impulses. Einstein’s insights into the Logos; the beauty of Beethoven’s music, represent something transcendent. Highly trained composers can compose in the style of Beethoven, but this is strictly imitative. It is possible to pull from the Ungrund something similar to Beethoven, but only in conscious imitation of him, and the results are derivative. What each musician pulls from the Ungrund, ideally, is a reflection of him and his interaction with the Great Mystery. It is a gift from the divine; a gift uniquely chosen for the recipient and in cooperation with him.”

The left hemisphere focuses on discrete objects, the right hemisphere on intuitive awareness of context. The RH is also what connects us to reality. The LH only involves concepts, maps of reality, and foregrounded aspects of a broader background. As such, LH breaks reality into bits. Determinism is very much a LH phenomenon. It is a theory, not something derived from experience. No one experiences determinism. And, in typical LH fashion, it imagines reality as broken into chunks; as separate events in which events are conceived of as causes and effects. Iain McGilchrist argues that reality is actually a continuous flow and in the process he resolves Zeno’s paradoxes. An arrow reaches its target because it is in a state of constant movement. If one freezes the arrow and imagines it occupying some particular position in space, movement is eradicated from the conception of the flying arrow and then the arrow will never reach its target. This is actually how Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle functions. To know the position of a particle is not to know its speed. And to know its speed, is not to know its position. By conceiving of the particle as stationary, as being in particular spot, one can no longer perceive its motion. The particle or the arrow is not moving through an infinite series of “points” either. Those imaginary points have no dimensionality. A line is not a series of points; it is continuous. By misconstruing a line as a series of juddering points, the arrow then needs to move past all those points. Since there is an infinity of them, the arrow never reaches its target. But, of course, it does reach its target. Non-dimensional, non-extended points, are nothing. Because they lack extension, they cannot compose a line, in a similar way, straight lines, no matter how small, cannot make curve.

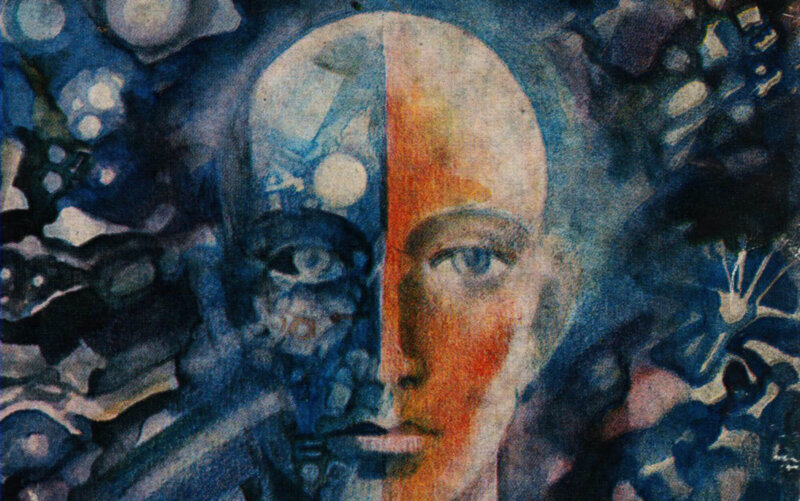

The image that comes to mind regarding determinism is to think of reality as akin to an explosion of dynamite that sets off another explosion of dynamite – discrete moments of cause and effect. If reality is instead a flow, then this cause/effect paradigm goes out the window.

The modern concept of cause and effect is highly artificial. Aristotle identifies four causes. Formal, efficient, material, and final cause. The formal cause of a house is its blueprint. The efficient cause is its builders. The material cause are the materials used in its construction. And the final cause is the reason the house was built in the first place; namely, to provide shelter for humans. The final cause is the most important because without it the materials will not be purchased, the blueprints will not be drawn up, and the builders won’t be engaged. We tend to focus on the efficient cause only, but Aristotle’s account is more complete. It is also not mechanical or deterministic.

Isolating “a” cause is also a strange LH abstraction for other reasons. The universe is a complex whole; a Gestalt. The universe has to be pretty much as it is in order for something to happen the way it does. If someone asks, “Why did that happen?” The real answer would be something like, “Well. In the beginning was the Big Bang. Due to slight deviations of uniformity from the plasma that emerged, gravitational forces brought some of it into lumps that became stars creating heavier elements through the process of fusion and bringing light to the cosmos. Then…” In other words, the whole history of the universe had to occur as it did. Our solar system had to come into existence and life had to emerge and then human beings needed to evolve and on and on. It is not practical to recite all this every time something happens, so we focus on a little part of it and act like it is taking place in isolation. This makes it seem like reality is starting and stopping all the time rather than unfolding in flowing time. The starting and stopping jerkiness thus created in the imagination then gives rise to the determinist mechanical picture of reality. We take a re-presentation of reality done for practical purposes and confuse it with the continuous flow of reality itself.

Lee Smolin points out that the theories of physics cannot be applied to the whole universe. In order to study some part of the universe, we regard it as dynamic and changing, while the rest of the universe is treated as though it were static. But, the truth is, everything is dynamic and changing. Stasis is postulated for practical purposes only; it is a kind of pretense making physics possible.[9]

When analytic philosophers try to explain the difference between mere correlation and real causation they cannot do it. They point out that saying given a cause X, the effect Y “necessarily” follows, does not mean logically So, in what sense is the effect necessary? It is not. The most one can say really is that the effect does follow after the cause. But, correlated events simply “do” happen too.

Symbolic logic is completely unable to capture causation either. So, any sense of causation is simply lost as soon as symbols are introduced. If-then hypothetical statements have nothing to do with causation. In logic, if the consequent is true, then the entire statement is true and that makes a nonsense of common sense or causation. For example, “If hula hoops were invented in 1963, then the current offerings of Netflix are pitiful.” So long as it is true that the current offerings of Netflix are pitiful, and it is, then the entire conditional statement is also true. Never mind that the statement is stupid and antecedent and consequent are unrelated.

If determinism depends on causation for its meaning and we cannot define causation then determinism is on much less firm ground than it would like.

“If you did not choose a good life, why should it worry you if you are denied a good life? I have no choice about how I argue, or what I do, and neither do you. What does “you” are “worried” mean in this context anyway? Automatons are neither “you” nor “worried.” The illogicality of determinists is one of the most abhorrent and repulsive aspects of determinism. As a fan of logic, properly applied, I admit I find this distressing.”

“A good life”, put another way, is simply satisfying one’s preferences. You are incapable of “choosing” anything except attempting to satisfy your preferences. People have chosen lives which they’ve mistakenly thought would lead them to their preferences, but nobody has ever consciously chosen a bad life for themselves, where they knew their preferences wouldn’t get met. We are not actually capable of doing such a thing.

So, we are back to preferences again. This article: The Metaphysical Status of Preferences is my response.

We try to determine, using our minds, what we think the good life will look like. This we choose. Our preferences often follow these freely chosen goals. So, while the preference might not be chosen per se, what it is a preference for

Plus, as stated before, we choose if and when to follow our preferences. To imagine otherwise is to commit a self-sealing fallacy. It is a common experience that we often do things that we would prefer not to.

I wonder if this is the reason Sam Harris chooses “preferences” as the thing that means we are not free? Sometimes, I do what I need to do rather than what I prefer. I drive my spouse to the airport, though I might prefer to sleep in. Someone can then say, that just means your “real” preference is to not make your wife angry or disappointed with you. Whatever you actually end up doing expresses your real, overriding preference. But, that becomes a tautology. It becomes true by definition that we follow our preferences. Since no exceptions can be found, due to the meaning of the word “preferences,” one is no longer making a statement about how the world functions, but just the meanings of words. As such, no counterexample will ever be possible. In the world of facts, however, hypothetical counterexamples are always possible. That is how we know we are dealing with the world of empirical reality.

In an earlier piece, RP repeatedly asks me to provide a single example of someone not following his preferences. He only does that because he has already defined any action as something that follows one’s preferences. He has set up his No True Scotsman fallacy and is encouraging me to step into it with him. In other words, it is a trick.

Later in a separate piece, RP claims that it is axiomatic that we always follow our preferences. An axiom is supposed to be self-evidently true. Since the concept of a preference has nothing to do with being forced to act on this preference, it is not remotely axiomatic. We have lots of preferences that we do not act on. And we can all agree that we routinely do what we would prefer not to, such as cleaning the bathroom, taking the dog for walk in the freezing cold, and so on. Something cannot be axiomatic if anyone can come up with plenty of exceptions.

And if you argue against that, you’d reveal your ignorance of how determinism actually works,

I am arguing against physical determinism. RP seems to have a kind of preference determinism in mind which I am satisfied I have refuted as being mind-dependent, while determinists regard conscious experience as causally inefficacious.

““Preferences” are irrelevant. Who gave you those preferences? You are a slave, a mechanism, and a nullity. Its do not have meaningful preferences. You cannot act on those preferences, since only agents act. You, unfortunately, are caught up in a meaningless charade. You are not enough of a determinist. Get with the program!”

You say: “Its do not have meaningful preferences”. What does “meaning” have to do with anything? This is skirting an appeal to emotion. Because you don’t find it “meaningful” enough, it therefore must be untrue?

It has been explained over and over why RP’s attempts to appeal to “preferences” are nonsense given his metaphysical assumptions. As stated right there, preferences only make sense given agency. Being railroaded into an action is the opposite of acting on a preference. What kind of preference is that? It is not meaningful to speak of preferences in such a context. The car does not “prefer” to go forwards when I put it in drive and in reverse when I put it in reverse. It does what it is commanded to do by something other than itself.

RP’s reply is obtuse for that reason.

Calling a statement meaningless is not an appeal to emotion. RP often seems to act as though no reasons have been supplied for an assertion when they are right there staring him in the face. I don’t get it. It becomes a pantomime act. “Watch out for the monster!” Turns around while the monster hides. “I don’t see any monster.” Turns back to face the audience only for the monster to reappear. “There. There.” Makes sure the “monster” has time to hide before turning around again to look at an empty stage.

Nihilism is the belief that life has no meaning; that it is a meaningless joke. It is an understandable position to want to avoid that conclusion. RP is suggesting that it is enough to have preferences to have a good life. I am arguing that meaningless preferences are undesirable because nihilism is undesirable. There is nothing hyper emotional about this claim.

Philosophy necessarily has an intuitive component unless we stick to mathematical logic. Actually, that involves intuitions too. New insights into mathematical logic are derived from creative, intuitive, and imaginative thinking. See Gödel’s Theorem.

If the life of a slave (actually worse than that) and a mechanism do not repulse RP then that is his prerogative. This style of argument is called a reductio ad absurdum. We assume for an argument’s the sake the truth of an assertion and see if we can derive a contradiction. In this case, RP’s claim that determinism is an utterly fine position should conflict with the belief that he does not want to be a slave or a mere mechanism programmed to do what he is told. There is no conflict for RP, supposedly, so the argument does not work in his case.

This cannot all be a matter of mere logic. What we picture as a worthwhile life is relevant to this discussion also. Some of that evaluation will occur on an intuitive and partly emotional basis.

Given RP’s failure to find this repulsive, he is happy to continue being a determinist.

Obviously, neither determinism nor free will can be proven, so one must have a motivation to argue for one rather than the other. My motivation is that I want to continue to lead a meaningful human life where I make my own decisions and suffer the consequences.

One possible attraction of determinism is that it avoids moral responsibility. People do not like the feeling of guilt and determinism provides a handy way of avoiding it.

Subjective meaning, too, has no bearing on the truth – for any argument.

That would be true if we were debating a mere matter of scientific fact. But, we are doing philosophy. In particular, we are debating the meaning of human existence. RP seems to have been arguing that a good life is a reward of some kind and that lots of other things do not matter, like the fact that we will not have chosen that life, and that someone or something else has decided that such and such is a reward. That is a judgment call and thus subjective. When someone introduces subjective elements like that, and we both have, you can try to nudge them in your direction by asking questions like, “Do you really think such a life would be worth living?” RP’s answer is “yes.” Mine is “no.” And I am busy providing reasons for that “no.” Some of them have to do with feelings since we humans care about such things.

You may think it’s meaningless. I don’t. Regardless of whether you find preferences you did not choose “meaningful”, you possess them. You experience them. And sure, this may, indeed, be a charade of sorts, but if programs can feel a sense of reward for meeting preferences they did not choose, why do you insist we cannot? What law of logic or nature is that breaking?

RP and I have fundamentally different intuitions concerning meaning here, hence partly why we are on opposite sides of this debate. I don’t want my life to be a charade and will fight to avoid that outcome.

I disagree that programs feel anything, let alone a sense of reward for meeting unchosen preferences.

I dispute that the word “reward” applies to machines in any relevant sense to this discussion for reasons already stated.

“There is no you. There are no choices. Every single determinist will back me on that one. Choice is a pure illusion. It does not exist! You already said so in your opening statement. You are doing what you are programmed to do by genes and environment, but really, the Big Bang. Please make up your mind if you really want to be a determinist or not.”

I’d like to talk to these mystical “100% of determinists” who believe that. Strange, then, that none of the big names or any of the smattering of lesser names in this discussion that I’ve read/heard has ever mentioned not being allowed sense of self. No real choices, sure. You’re conflating that with “no sense of self is therefore possible”, as you feel it makes determinism much easier to defeat. Aka: Strawman.

The position that there is no meaningful “self” is one I am claiming is logically implied from the position of determinists. It is not one actively embraced by most determinists, although it is adopted by Sam Harris (see below). As stated elsewhere, without agency, all that really exists is a sequence of events. There is a stream of physical cause and effect and what we call “you,” and “I” are metaphysically indistinguishable from that stream. Except, RP thinks experience is significant, though it is not an experience that belongs to anyone to any real degree. I have analogized it to “locked-in” syndrome and thus a kind of living hell.

Sure enough, by the end of this discussion RP accepts that “I” and “you” are meaningless concepts designed to make us feel better about living in a deterministic universe. Never argue with someone who violates the law of non-contradiction. I have done so anyway in the hope of finding something edifying in addressing an extended argument by a determinist.

Sam Harris in his podcast #159 on the topic of consciousness with his wife Annaka Harris agrees that there is an essential connection between freedom and the existence of the individual. Since Harris does not believe in free will, he does not believe in the self. A key part of RP’s argument is that we must always follow our preferences and we do not choose our preferences, which seems to be derived from Harris’ book on free will. So, the Harris’ denial of the existence of a self seems particularly important. In fact, both spouses adopt the “there is no self” position, seemingly inspired in part by Buddhist meditation, too. Annaka Harris asserts this position in her podcast with Lex Fridman #326. She prefers to refer to herself in the third person, saying something like, “this assemblage of body parts and behaviors known as Annaka Harris.”

If this is how you are presenting determinism to your students, no wonder they think it’s batshit.

There being no self is the least of it.

Actually, I present to them two main articles proving that arguing for determinism is a performative contradiction and one of the more insane things philosophers have ever proposed. The articles are this one and this one. It is right up there with denying the existence of consciousness.

My students are not sanguine about the existential consequences in the manner that RP is and that is another reason they do not embrace determinism. The studies cited above show that the consequences are in fact horrendous.

We choose things but have no choice over what we choose. “Pick a number between one and one” is not a free choice.

“So, you have “preferences.” What does that even mean in this context? Who cares? Does a computer have “preferences?” No. You are a computer. Nothing more.”

Yes, computers do have preferences, as discussed. I wrote all of the above before I read this sentence and now I fear that you might not actually know how computers work.

Computers do not have preferences in any way analogizable to human preferences. They are, by definition, rule following devices. They do what they are programmed to do. They do not follow their “preferences.” If this happens, do this. If that happens, do that.

I have been careful to make sure I thoroughly understand what an algorithm is and I have spent months of my life making sure I understand Gödel’s Theorem and The Halting Problem and thus the limitations of those algorithms. I have published the results of those efforts and been corrected by one of the commentators. An Indian physicist directed me to Brains, Minds, and Computers by Stanley Jaki to improve my arguments and understandings and he notified me that I had failed to distinguish axioms sufficiently from Gödelian propositions partly because they share the common property of being clearly true, but unprovable. I also made a thorough study of The Emperor’s New Mind and Shadows of the Mind by Roger Penrose in preparing those articles.

“There is no “I.” Just circuits. So, no there is no “I” perceiving anything.”

Sorry to beat a dead horse, but I just want to clarify your thoughts: You obviously take EXTREME issue saying “I”, or anything of the sort. I get that. But would you agree that there is something – some entity – doing some kind of perceiving, yes?

I’m not going to agree that there is a deterministic entity that perceives. Perception takes place in minds. We perceive through our eyes, but with our minds. Kepler “solved” the problem of perception by stopping before it got to the mind. See this article here.

That is “I”, for future reference.

“What exactly is “experience?” I do not believe that is well-defined. That would require consciousness and an “I.””

I’m not sure I could concisely define “experience”, either, but what is it when a computer program can perceive data? Record data? Recall data? Interpret data? I’ll ask again: Does a computer have consciousness? Do you think they a “them”? No, right? Yet they can do the exact same things as would be included in any definition of human “experience”, and yet you also maintain that a conscious and an “I” is required. Arbitrarily. It’s a double standard.

The words “perceive,” “record,” “recall,” and especially “interpret” as applied to computers is strongly metaphorical and not what human beings are doing. A computer has no understanding and thus all these things we are projecting onto the computer from our human point of view. The zeros and ones might have meaning to us as “recording” something. The computer has no such conception. In fact, it has no concept of anything.

Experience takes place within consciousness, although the degree of awareness differs. Aristotle makes a distinction between passive and active nous (soul). Signals from our skin inform us about the feel of the shirts on our back, but we usually pay no attention and it forms no part of our experience. It remains a potential only. That is passive nous. Active nous is when we actually pay attention to those perceptions and they enter conscious experience. Computers are not, as yet, conscious.

If human beings are computers, then I deny them the honor of personal pronouns. We turn computers off. If humans are computers, we can turn them off too. The only thing stopping us would be some woo woo magical thinking.

I know you haven’t yet answered, but I’m expecting some form of moving the goalposts in response to this. What else could you do which would preserve your beliefs?

“At this point in the argument, you are describing a horror show. You admit you have no control over anything. Events are simply happening.”

More appeals to emotion. Why “horror”?

At this point, I find RP’s emotional obtuseness also horrifying.

I have done absolutely everything I can to communicate how distasteful, nihilistic, life and meaning destroying I find the thesis of determinism. The studies cited above reveal the life harming consequences of believing in determinism. It is an atom bomb dropped on life as we know it. The consequences are all negative for embracing this belief. Horrific is merely descriptive. I wonder which emotionally neutral term RP would prefer? And would the same meaning be communicated? I imagine he would prefer “suboptimal.”

I am attempting to persuade students and other readers that RP’s depiction of human existence is absolutely horrible. The horror entailed by his worldview is relevant.

Imagine that someone has to choose between two realities to inhabit, and they must inhabit one of them. If I care about this person, then an entirely neutral and “objective” description will not be sufficient if one of those realities turns life into a meaningless joke. In that reality, all behavior is compulsive, all decisions made by mindless physical forces and even how you feel about it decided by physics.

The objective and neutral description would be actively misleading if an active life choice must be made.

It would be like explaining to a child, or an alien, that they are about to be eaten alive by a wild animal and this individual has no conception of what that would actually be like. Saying “your pain receptors will be activated and your amygdala will be more active than usual” as an act of communication is simply not good enough. We are not robots. We feel things. And determinism, if embraced, is absolutely dire.

I imagine many people have seen science fiction scenarios where prisoners have their minds altered to think that they are enjoying their captivity. Most viewers will find this especially creepy. It is one thing to be a slave. It is another thing to be compelled to enjoy it and maybe sing songs of praise to your master. This is the kind of thing the determinist envisions.

Compulsory sex is rape. Is it still rape if you enjoy it? Yes. And there can be only rape where consent is impossible.

RP regards mention of rape in this context as absolutely unconscionable and emotionally manipulative. I am entirely within my rights to mention this fact about the logical and moral consequences of determinism. It might set RP’s hair on fire, but that is acceptable. RP thinks I should stick to writing about emotionally neutral topics, presumably like eating tuna sandwiches and the like, that won’t set anyone’s amygdala off.

I am indeed trying to appeal to RP’s right hemisphere which is relevant here since we are partly debating what a worthwhile life might look like. And what a horrible life might be like. Intuition and emotion necessarily come into those topics, not mere facts.

Emotion and intuition are necessary for understanding the world. Those who are emotionally impaired due to organic problems in their brains simply cannot function properly. Autistic people fall into this category and their lives are worse for it.

Concerning agency, it doesn’t matter. There is a clear delineation – as far as human experience is concerned – between human action and a puck on a plinko wall. We collectively refer to that difference as “agency.” If you don’t want to define it that way, so be it, but the rest of the world does.

RP appears to be arguing against his own position and in favor of mine here. I agree that human experience and human action is significantly different from inanimate objects, in particular, we humans have agency and pucks do not.

It is RP and determinists who reject the idea that humans have agency, not me.

“The world” defines human action as agential because “the world” has not adopted determinism as its philosophical position. In fact, even many determinists admit that society could not function at all properly if determinism became a widespread belief. Determinism gets rid of moral responsibility for a start and thus the crime of murder and rape could no longer exist, since both rely on intent, and duress obviates legal guilt.

“In this mixed up way of thinking, “you” are somehow conscious, but trapped. “You” have “experiences,” whatever those are, since they have not been scientifically defined, and you think some are “good” and some “bad.” But, someone/something decided that for you.”

And you disagree? I know I’ve asked this already but provide me right now with where your preferences which guide your beliefs and subsequent actions come from.

“Your opinion (again there is no you, but let’s just run with it) that something is “good” or “bad” has been assigned by someone or something else.”

You start to catch on, here. You don’t believe the self can coexist with determinism, and yet even you are capable of saying “I don’t agree with this, but this language is useful for explaining what I’m trying to explain, therefore […]”. Something certainly exists, even if determinism also does. It’s the same thing you begrudgingly refer to as “you” in your above quote.

I’m not catching on to anything. I am doing a “for argument’s sake” move. I don’t agree with this, but, counterfactually, assuming it were true for a second, then…

“They could have assigned you to think something else.”

A bit off the path but no. There is no “they”. It is physics – nothing else.

I was being a bit poetic. Let’s just go with physics. Treat my “they” there as being a placeholder for whatever RP wants to put there, which is what it was intended to be.

“There is no “convincing” if determinism is true. There are merely sequences of events. You move that way. I move this way. You feel X. I feel Y.”

You just explained the psychological mechanics of “convincing” someone within determinism whilst pretending you cannot convince someone within determinism. And you’re exactly right in the mechanism – that’s what it is to convince someone. I say x, you perceive y, and you reevaluate. I then might say z, “move that way” and you “move this way” and you’ve become convinced.

There are no “psychological” mechanics here. In a world of automatons with no free will, psychology is a meaningless category. There is no such thing as “reevaluating” given the limits of RP’s metaphysics. RP cannot make mind causally efficacious when it suits him while believing that physics alone is what makes things happen. Mind, and “convincing” are just meaningless phrases in this context.

Such an “explanation” merely explains “convincing” as an activity away and makes it indistinguishable from any other non-psychological event.

There are literally “arguments” in computer programming.

There are not. Unless, the scare quotes around “arguments” are taken very seriously as indicating that they are not really arguments at all. Programmers might write an argument and put it in a computer, but that it is the programmer’s argument, not the computer’s.

A person cannot be said to be arguing if he has no understanding of the words he is using. Computers have no understanding of anything. They are mindless machines following their programming.

Twenty years ago, another person tried to tell me that computers have arguments and he also had a background in computer science. Is there something about programming that leads to anthropomorphizing computers?

A computer no more argues for a position than a toaster.

Computer virus code can ‘argue’ with antivirus code. If the virus code successfully “convinces” the antivirus, it will let it in the system. – An example of a deterministic, causal, mechanical “automaton” successfully “convincing” another.

These are very obviously metaphors and nothing more. Even people do none of those things in physical determinism, let alone computer programs.

Again, RP gives the game away by scare quoting “argue.”

If I reply in phonetic Mandarin but I don’t know what I am saying, I cannot be said to be arguing even if what I say is in fact a premise supporting a conclusion to someone who does speak that language. I am, however, verbalizing.

“You wrote: “When the robot makes a “choice” to veer left to follow the line, it has done nothing but reference its programming and equations and variables to their inevitable conclusions.””

I thought it obvious, but I was using “choice” the way you do.

This whole debate is about the existence of choice. There is a reason RP put scare quotes around “choice.” Obviously, we do not use that word in the same manner. I believe in choice. RP believes in “choice.”

Humans do the same thing – follow the same mechanism – when making decisions as does this robot, and yet we call one a “choice” and one “following programming”. My point is that they are literally the same thing. There is no additional magic sprinkled by an invisible wizard which makes our choices free of causes we did not choose.

I understand that RP thinks they are the same thing. Obviously, I do not, so I am not going to concede that they are the same thing!

We both have difficulties with our positions. Arguing for RP’s involves a performative contradiction. Arguing for mine involves something uncomfortably close to an “additional magic sprinkled by an invisible wizard.” I would love to say otherwise, but I cannot. Since we are in fact arguing, to be consistent, then in bothering to argue RP is accepting that additional magic. I need a little magic, while RP describes a life of utter nihilism and pointlessness of the sort described by autistic people and schizophrenics who have lost the sense that either they or the people around them are real, and instead experience everyone as a robot and imposter; as mere automatons simulating human beings. Choose your poison.

“A preference implies goals and purposes. I prefer wine to sewer water. I prefer pleasure to pain. I intend to strive for one rather than the other. There are no goals and purposes in determinism. Determinism is predicated on cause and effect, not goal-driven behavior.”

We can know with absolute certainty that this is false, as computer programs have goals and preferences, and we both would agree they have no free will. Therefore, goals and preferences necessarily are possible within a deterministic system. Not to mention: Why do you arbitrarily believe that cause and effect cannot lead to goal-driven behavior?

Computers have no minds to have goals or preferences. Since they understand nothing, they just follow their instructions presented by others. Programmers have goals and preferences and use computers as tools to achieve them. Demis Hassabis agrees with this “tool” description.

Demis Hassabis, CEO of DeepMind Technologies, responsible for AlphaGo and AlphaFold (protein folding) has been described, by Lex Fridman, as the person most likely to preside over the emergence of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) were that to ever happen. In his interview with the roboticist, former Stanford professor, and podcast host, Lex Fridman, Hassabis made two pertinent comments. One, computers are tools and nothing more. Two, he has never seen any evidence of sentience in a computer program. He regards the existence of life and consciousness as a complete mystery. Hassabis thinks that intelligence might be separable, in principle, from consciousness since he does not think dogs are very intelligent. I disagree. Hassabis does not pretend that his claim is anything other than speculative. We have no evidence that intelligence and consciousness can be separated. And, Hassabis is perhaps overloading the term “intelligence” when he claims that dogs are not intelligent. They are goal-driven, like all organisms, and can improvise intelligent solutions to problems, just as single-cell organisms, such as white blood cells, can and do. Hassabis calls dogs unintelligent only in comparison with humans.

It is not arbitrary to think that cause and effect cannot lead to goal-driven behavior. Causes push from behind. Goals pull towards the future. Goals are yet-to-exist states of affairs. If something does not physically exist, it cannot cause anything in the manner of physical determinism. Teleology has been eliminated from the scientific approach to the world. Science, in general, denies the existence of goal-driven behavior. Aristotelian “science” included “ends” (a telos) and goals. Modern science lets “goals” exist only as a place-holder until a mechanical explanation can be found. Once it has been found, they eliminate any talk of “goals.” Unfortunately for scientists, biology is completely unworkable without reference to goal-driven behavior, depending on the specific area.

“That does not make your preference good. It gives no reason for thinking your preferences should be satisfied. And, incidentally, there are no “shoulds” in determinism.”

Absolutely true, on all 3 points. I never claimed otherwise, unless I misspoke with a rogue “should”, or something.

A little far afield, again, but Kant’s hypothetical imperative works perfectly fine within determinism. Nobody can say they ought to have the preferences they have, but IF they are trying to satisfy their preferences, there are certain “oughts” that can, more or less, be proven – though not necessarily very specific ones. Maybe that’s too off topic.

Hypothetical imperatives involve goals. See above. Goals can, however, be provided by programmers, though it is their goals, not the computer’s.

“Computers cannot “attempt” anything. That is a word borrowed from the language, metaphysics, and ontology of agency. That is intentional language involving goals.”

Entirely incorrect. “Attempting to establish a connection…” What is going on there? What is the computer actually doing, then? I mean, I realize that a human wrote that message in the code, but what else would you call it that the computer is doing? I’m just trying to figure out if this is more a semantic point or if you genuinely believe that a computer doing something that resembles in every way an “attempt” to do something is not actually an “attempt”, somehow.

In many instances, using intentional language is highly efficient. However, it becomes problematic if we are trying to figure out something’s metaphysical status. Then, we need to be extremely careful with our language and not introduce mental categories into inorganic entities. An ax, a tool, is not attempting to cut down the tree, the woodsman is. A computer does what it is programmed to do and it is convenient to call that “attempting” for the purposes of communicating what the programmer wants it to do to other humans. It is, of course, not literally attempting anything for real.

I realize that RP does not think we humans are literally attempting anything either. Our actions are perfectly mechanical and robotic for the determinist. A leads to B, B leads to C, and so on. Philosophically, it would make more sense for RP to eliminate words like “attempt” both from descriptions of humans and computers. In daily life, however, it will remain useful to retain intentional language in both instances.

“Nobody can be convinced of anything if free will does not exist. “You” can cause “me” to alter my programming, but “you” are not actually “doing” anything and neither am “I.” A sequence of events has occurred. End of story.”

If you want to think of it like that – a sequence of events – fine. Your cross to bear. The rest of us use language most suited to conveying the ideas we wish to convey, and in a manner that pleases us – satisfying preferences. “You”, “me”, “doing”, and “I” are certainly among them, and not at all mutually exclusive with the possibility of determinism.

As I say, one mode of speech is suitable in one context, and another in another. I don’t believe in any of this deterministic stuff, so I don’t use that language at all, except when interacting with determinists on the topic of determinism!

The language that pleases RP, in this context, is enormously misleading and simply muddies the water of what we are attempting to discuss.

Your view of how determinism would work:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. A series of events happened. The end.”

Except without the concepts of “best” and “worst.”

Strangely, that is not as rewarding to us humans as pretending we all have agency and free will and all of that which you are clutching to your chest. Our preferences are better met with all the gooey middle parts. With pretending we have vast choices and wallowing in our ignorance of the complexity of cause and effect. With heaping meaning onto our inevitable fates. That’s why we use words like “we” and “I” and “convince” and “goals” and such. But it is nothing more than a reward system attempting to satisfy our preferences.

RP gives the game away entirely in this paragraph. After arguing that we still have agency if determinism is true, that personal pronouns still make sense if determinism is true, that words like “convince” and “goals” still make sense if determinism is true, he admits that none of this is true. It is “nothing more than a reward system attempting to satisfy our preferences.” Except “rewards” and “preferences” do not exist under determinism either. See below.

Determinists are hypocrites. They say one thing and do another. A good test of what someone really believes is how he acts.

Most determinists seem to acknowledge that they cannot live their philosophy.

Some pretty good comedy could be garnered from having a determinist talk to his girlfriend in a manner consistent with his determinist beliefs. The left hemisphere is mostly devoted to the perception of, and thinking about, inanimate objects. Since girlfriends would have interiors of no real significance under determinism, a character playing the determinist could say, “My serotonin seems to be edging upward, my dopamine is at levels indicating that my system is enhanced by your proximity. I guess this means my biological processes are pushing me to say things like “I love you,” whatever that means.”

We don’t have any choice about what we pretend and don’t pretend under determinism. That particular contradiction, that we have a choice about whether to use a certain kind of language or not and so on is one of the things I most dislike about determinists. My metaphor for this behavior is that determinists point to a river of causation leading to its inexorable destination, and then they pretend to step out of that river and make real decisions concerning real choices.

Determinism is nihilistic. Since it is an unprovable hypothesis, just like the existence of free will, positive optionality suggests going with the option that does not render all of human existence meaningless.

“But it is nothing more than a reward system attempting to satisfy our preferences.” Thus, I was correct to isolate the topic of preferences and give it its own little article. I disagree that “preferences” make any sense under determinism, or “rewards.” They have no more ontological reality than “I,” “we,” and “goals.” Preferences and rewards make sense as concepts only in a world of causally efficacious consciousness. They are, by their nature, mental items implying top down causation; the mind affecting the body. “Rewards” are incentives to a certain kind of behavior. And “incentives” imply minds. We do not talk about rewards and incentives when it comes to inanimate objects with no minds. It would seem to make the most sense for determinists to deny the existence of life as an unnotable and unidentifiable element in the vast causal stream of events. One I know does, describing it as a “poorly defined concept.” Rejecting the existence of things that cannot be defined is a distinctly left-hemisphere tendency. We cannot define knowledge either, and yet knowledge can and must exist, especially if one claims to know that knowledge is impossible. No such thing, rewards and preferences, exist for a hardcore consistent materialist, and thus determinist, so they must revert back to physical causes only.