Gnostic Reality and Horror Theology: Matt Cardin’s Guide to Modernity’s Apocalypse

The horror genre, despite boasting literary classics such as Frankenstein, Dracula and the Castle of Otranto (to name but a few), is not often associated with high intellectualism or any great degree of sophistication. This is largely due to the recent preponderance of horror novels, comic books, films and video games which offer nothing but comically over-exaggerated gore, generously sprinkled with gratuitous violence and tasteless, superfluous, nudity and pornography. That the horror genre has been in decline for some time, especially from the 90s onwards, is not a controversial position to take. One only need revisit the Scream film series, which, in their self-parody, brought the seemingly terminal malaise of the horror genre to the fore. Ever since, there has been a feeling that the genre has exhausted itself into irrelevance, having collapsed under the weight of its cliches and contradictions.

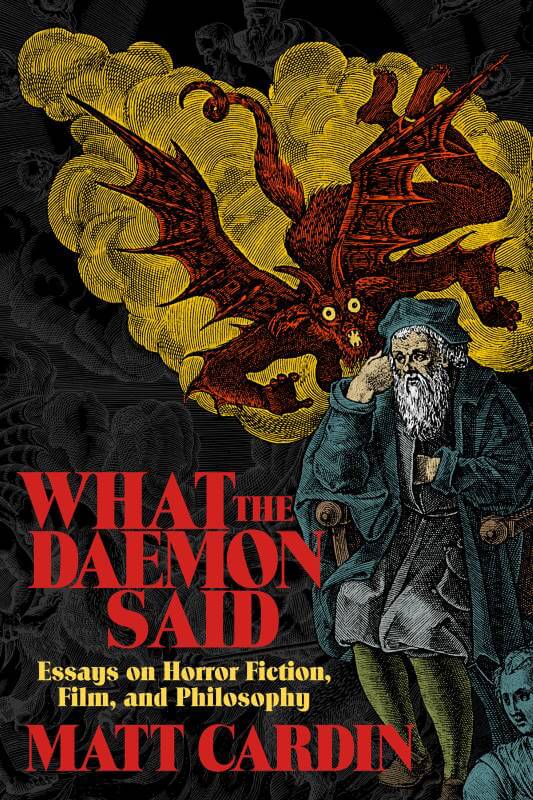

Matt Cardin’s What the Daemon Said: Essays on Horror Fiction, Film and Philosophy shows us that not only is the above an unfairly limited synopsis of the world of horror, it is, in fact, a genre that is intellectually versatile, profound and in many ways essential to our understanding of modernity, and worth our re-consideration. Horror deals with the timeless subjects of the human condition but in a very specific context: that of post-Enlightenment modernity and the domination over society of the Whig-Darwinian (prototypically Baconian) paradigm, whose defining features are those of alienation, revolution, and secularization. Never before in history had there been such a renunciation of the past, of the very concept of order, and of any sense of Transcendence. This process and ideology have served, ever since, as a justification of what amounts to an open and brutal war against nature itself, be it that of man, plant or beast. In this sense, horror’s role as a cultural phenomenon, as implied by Cardin’s conclusions, is threefold: it is modernity’s harshest critic, its most profound and descriptive narrator and, ultimately, its punishment for its transgressions. Horror is the judge, jury, and executioner of modernity. It has also, paradoxically, become reality itself.

The world in which horror is thriving, as described by Cardin both as a horror writer and cultural and literary critic, is fully consistent with Erich Voegelin’s description of the core pillars of Gnostic modernity. These are: alienation due to a sense of lack of fulfilment in life; a revolt against the conditions in the world that are felt to be the source of this alienation; belief in esoteric (also alchemical-scientific) knowledge and political action as the cure to all of the world’s ills; and, finally and logically, the rejection of Transcendence and with it any possibility of Good (leaving us only with Evil).

As Cardin explains in the interviews contained in the book, though brought up as a devout Protestant in a strict and observant household and holding an MA in religious studies, his religious beliefs are rather eclectic and include a pronounced fascination with Gnosticism and other esoteric theologies (both within and outside the Christian tradition). Modernity’s alienated, secularized Gnostics as understood by Voegelin, and also the ancient ones who saw the material world, including their own bodies, as a form of evil imprisonment, experience life in the world in a state of living horror rather than goodness, evil rather than blessedness. But what do we mean by horror? It is not that of mere terror or fear but of something that:

rips through what sociologist Peter Berger called the ‘sacred canopy’ of our understanding of the universe, and the result is pure horror…defined as a combination of fear and revulsion’’ a violation by “things that should not be-these cause horror because they punch through that subjective-objective divide and threaten to assault us at our core.

Ironically, those of a Darwinian-evolutionary disposition come worst off in this for they would have to admit the reality they believe in and promote in books such as The God Delusion and God is Not Great is one of horror where:

we are the unluckiest beings on the planet, since our particular set of biological adaptations has resulted in the development of a nervous system capable of self-aware thought, which is now able to recognize with full, stark, staring horror the awfulness of our situation, cosmically and ontologically speaking. ‘Consciousness is a disease’ and all that.

The sub-genre of “cosmic horror,” to which Cardin dedicates a large portion of his book through his thoughtful essays on the works of H.P.Lovercraft and Thomas Ligotti, represents the reality of the world of total secularization and atheism. That is, if secularism and atheism were honest with themselves and not clinging to the aesthetics and ethics of Christianity, while jettisoning the very metaphysics which gave us the aesthetic of Beauty and ethic of fraternal love. The universe is not an indifferent Newtonian machine characterized by a sense of detachment and “scientific’’ decorum. Instead, it is a malign entity, an active foe of humanity—the whole universe has become our enemy. There is no escape for humanity; outer space is controlled by demons, the seas and oceans are the realm of the evil deity Cthulu. The monsters are in control of the universe and are out to destroy us. A world created by monsters for monsters is both malign and indifferent, for it only cares for mankind only in as much as it seeks out its destruction. The nihilism of this proposition is self-evident, for what is sought is annihilation for the sake of annihilation, not a rebirth or a new beginning. What remains in such a world is nothing but a combination of despair, terror, and disgust. In another word: Horror. As Thomas Ligotti put it in The Bungalow House, in such a world “there is nothing to do, and there is nowhere to go, there is nothing to be and there is no one to know.” This is nihilism beyond nihilism in the existentialist sense. It is also an accurate assessment of life in the shadows of the Baconian experiment.

Cardin also convincingly asserts—in the many astute and profound essays in this collection, covering the works of authors such as Ligotti, Klein, Lovercraft and Shelley, George Romero’s zombie films, as well as subjects such as angels, demons and vampires—that horror, as a genre, has a deep connection with spirituality. It is not only the exploration of spiritual themes that is relevant. Significantly, theological truths such as Hell, eternal punishment for sin, humanity as cursed, Satan and his demons, fire and brimstone upon the unrighteous, now forgotten or mocked in the secular West, re-assert themselves in the best examples of the genre. As Cardin himself puts it, and it is necessary to quote him at length:

…the dark and horrific side of Christian theology, and also, I think, of world religion in general, is central to the whole thing. But as you point out, it’s not openly acknowledged by a lot of people. How come? I think it is something to do with the softening and sanitizing of the human race that has occurred during the past few centuries. The post-Enlightenment attitude and worldview based on universal rights and dignity represents a brand- new meme of human history. By the antiseptic standards of our current Western and Westernized nations, every civilization in history has been inconceivably violent, not just in act but in attitude, and this includes their religious conceptions. Today we denizens of Western consumer society have largely cut ourselves off from such things, although the worldwide resurgence of fundamentalism, and also the increasingly bloody and trippy nature of our mass entertainments, shows the same impulses reentering through the back door.

To elucidate this point, Cardin analyses the Old Testament book of Isaiah in light of the genre, and finds that (to modern sanitized man) the book of Isaiah would appear to be the most extreme form of horror. This is unlikely to be contested by figures such as Richard Dawkins, whose constant complaints about the “brutality” of the Old Testament are now an accepted part of the New Atheist canon. This is because Dawkins, deep beneath his faux smile of benign atheism, lives in a world of horror because of his scientific atheism.

In his essay “A Brief History of the Angel and the Demon,” Cardin provides an illustrative example of his notion of “sanitization.’’ Whereas the demon has remained a creature of horror, the angel has been subjected, from at least the Renaissance onwards, to a process of artistic degeneration, having found “itself trapped in the bodies of chubby babies and doe-eyed androgynes.’’ It is now through horror that the angel has re-appeared as his true sublime self, a soldier of God and battler of evil (Satan and the demons) consistent with Second Temple Jewish and early Christian angelology. After all, one must not forget that in traditional iconography angels are depicted as imposing, fearless soldiers carrying swords and spears, fighting the good fight against the devil and his minions. Cardin’s notion that repressed, long-forgotten theological and moral truths re-appear and re-assert themselves through and as horror, is both profound and compelling.

The two best essays in the book are undoubtedly “Those Sorrows Which Are Sent to Wean Us from the Earth: The Failed Quest for Enlightenment in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein” and “Loathsome Objects: George Romero’s Living Dead Films.” Though they deal with a variety of different subjects, their common theme is as conspicuous as it is irresistible: the failure of the Baconian project, institutionally, intellectually, and philosophically, and, of course, the truly horrific consequences of its collapse. The dream of scientific utopia has turned, in its failure, and failure is inevitable, into dread horror and death writ large.

Fundamentally, Frankenstein’s monster is identified as a figure of potent critique of Francis Bacon’s open war against nature. Bacon ushered in the notion of “power-knowledge’’ which as described by Roszak and cited by Cardin amounts to a desire to “break faith with the environment, establish between yourself and in the alternate dichotomy called objectivity and you will surely gain power…in a true natural philosophy human knowledge and human power meet in one.” In other words, knowledge and the lust for power have become one as well as interchangeable. In Voegelin’s terms, modern thought’s abandonment of humble inquisitiveness and its replacement with the will to power, is the essence of Gnosticism, and also the core difference between ancient philosophy and modern philosophy (best represented by Bacon). Modern man no longer seeks to understand but only to control and dominate; Nietzsche, in this regard, was at least an honest expositor of modern philosophy whereas men like Dawkins and Neil deGrasse Tyson hide behind the ancient appeal of seeking truth while pushing techno-scientific domination and conquest.

Bacon’s scientized culture of “objectivity’’ has led human beings to being quantified in a multitude of ways, reducing the human experience to a set of statistics and observations. As Cardin points out, it is not surprising that modern philosophy has questioned the very existence of notions such as “the self’’ and “consciousness.” On a more practical level, the most recent and manifestly disastrous examples of “power-knowledge’’ were the inhumane Covid restrictions of the last few years, where the individual’s life and liberty were sacrificed at the altar of the impersonal, yet quaintly collective idol known as “Science.” That we have reached this stage was only to be expected, for “the history of Western culture subsequent to Bacon is a history of increasing human alienation from self and world as technical expertise grows ever more stupendous through the application of the scientific method to all areas of life.’’ The motto “Trust the Science” really means Accept Your (grotesque and horrific) Domination. And moderns, weak and pathetic as they’ve become, accept this fate.

Victor Frankenstein’s monstrous creation represents the abandonment of wisdom for Bacon’s lust for power over reality. Victor’s attempt to control nature through “forced objectivity… through a blend of naturalism and control’’ is the cause of his self-alienation. He moves from wanting to discover nature’s secrets to boasting he will conquer death. The fruit of the combination of the lust for power over nature and a proud intellect is the monster. The abomination Victor has created is a metaphor for the most radical self-alienation, for the relationships that are severed by the monster “include everything and everyone Victor has ever held dear.’’ He finds no consolation in the joys of art, literature, the seasons and even love. The Baconian monster he has created in turn remakes Victor into an “alienated figure, cut off from his own humanity as well as that of other people around him… he is all mind and no body.’’

If Victor is now a creature of pure intellect defined by “power-knowledge,’’ the monster is his lost irrational body. In contrast to the world of “objectivity,” the monster is pathological and extreme in disposition, and “is capable of both exceptional tenderness and exceptional cruelty.” He mercilessly kills Victor’s younger brother yet saves a girl from drowning; he both loves and hates Victor; he destroys Victor, only to then weep profusely over his dead body. If Victor is the embodied intellect, the monster is his complementary opposite, Victor’s “discarded visionary powers…his whole complex spiritual state.” Cardin concludes that, ultimately, the Baconian revolution has led to nihilism and the triumph of science is the triumph of nihilism. Frankenstein is “a parable about the failure of the Romantic quest for enlightenment in an age of scientific rationality…it is about the demonic power of science to prevent the fulfilment of the eternal spiritual quest.” For Cardin, there can be no doubt the ultimate message of the novel is one of despair as there is no redemption with the God of the Old Testament, the God of righteous Goodness who smites Evil and Sin, now gone from the cosmos.

The true end of the Baconian project, however, is not to be found in Frankenstein but in the zombie apocalypse as portrayed in George Romero’s Living Dead films. Romero’s zombies are not the creatures of Voodoo magic, where a necromancer revives and commands innocent people to do his bidding. Instead, they are “pure evil, out to eat the flesh of the living and controlled by nothing but their own instinct.’’ What’s more, they are portrayed as the perfect Baconian machines, purely “objective,’’ defined by nothing but “pure, motorized instinct…deep, dark, primordial instinct.” They do not need food to live; they kill and eat purely to satisfy their urge to consume, they are nothing but “cannibalistic eating machines.’’ What makes them even more horrific is that their cannibalism is “thoroughly pointless.’’

Romero’s genius is that he shows the complete failure of modernity’s institutions and beliefs to counteract the zombie apocalypse; what is worse, they cannot even explain the cause of what is happening. On another hand, this failure opens the door, with an even greater relevance, to the explanation suppressed by our culture of “power-knowledge’’: the spiritual one. Cardin offers a spiritual interpretation of Romero’s films. (It should be pointed out that Romero was raised Roman Catholic and his films deal with, even if only in oblique ways, Catholic themes.)

In all three films, Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead, “institutionalized authority is invariably portrayed in a dismal light.” The representatives of the military and law enforcement are portrayed as brutal, incompetent, sexist, racist and sociopathic. They are unable to distinguish man from zombie and zombie from man, and the only salvation from their brutality is their ultimate incompetence and inability to defeat the zombies. The manager of the television station in Dawn is happy to keep outdated rescue information on his show as it will attract viewers. The representative of science, Dr. Logan (also known as Dr. Frankenstein by everyone) quite openly states that the main purpose of his research is to find a way to control the zombies. Control, not knowledge, is the goal of modern science. Despite this professed “power-knowledge’’ objective, we later learn that his gruesome experiments with the zombies, amounting to little more than butchery, are motivated by repressed hatred for his parents. The explanations for the apocalypse, and solutions, offered by science, the media, and the military-industrial complex are defined by incoherence, inhumanity, incompetence and a lack of persuasive force. Welcome to the 21st century.

In contrast, despite making no claims to “objectivity’’ or calling upon evidence, the spiritual explanations sound more plausible, and have greater emotional potency, than anything the failed institutions of modernity can offer. In Dawn Peter (and the name is not a coincidence, as Cardin points out), offers “an explanation of the zombie plague that is short, apocalyptic and to the point: ‘When there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth.’’ In Day John (again, the name is that of an Apostle) offers a longer explanation to Sarah (another biblical name), the main female protagonist and a scientist, why she will never figure out why the zombie apocalypse had happened. John’s explanation is that the zombie apocalypse is a punishment from God and “so we might get a look at what hell was like.’’

Cardin implies that modernity has created a true hell on earth, one that it is unable to stop and even less able to understand. The consequences of modernity’s collapse, the zombie living machines, is hell in the truest sense of the word as there is no hope left, there is no salvation and no escape. In the world of modernity, as portrayed in the films “no God, father, or president, no military, scientific, political or religious form of authority guarantees or in any way promotes the survival of the living.’’ For Cardin, the spiritual message of the films is that “with no outside agencies left to aid us, we must face this nightmarish world of ravenous walking corpses without the possibility of redemption, without the possibility of being saved.”

So why then, as Cardin puts it, is there a “missing rainbow,’’ and “no cavalry racing to the rescue,’’ with “a bloody death the only possible outcome’’? It could be that the zombie apocalypse is not intended as a warning or a correction as were other biblical plagues visited upon the pharaoh, but is, in fact an act of final punishment. But then, would modern man turn to God at all in such a situation, the only path still open to him, or has he completely closed off that possibility? After all, the post-industrial era is, as Cardin cites Roszak:

The first period of human history in which spiritual alienation has been divorced from the possibility of anything better… until our own time, alienation has always stood in the shadow of salvation…it carried with it the implications of transcendence. Ours is the first culture so totally secularized that we descend into the nihilist state without the conviction, without the experienced awareness that any other exists.

As Cardin demonstrates, modernity has failed and has unleashed horror upon us. However much we pretend we can suppress the moral and the real, it will re-appear as horror. As a result, and as we can see in the state of the world around us, instead of the promised New Atlantis, what we got is hell on earth.