Guess Who Came to Dinner: Van Loon’s Lives

[The local children] . . . soon sensed that there was something mysterious about [their guests] . . . that they had gone through certain experiences which had left deep marks upon them . . . and . . . they tried to reach out to them by being very nice to them.

That we might speak to the dead is a wish universally felt. In fact, most of us have spoken to the dead, albeit only in dreams, and have woken with a sigh. To remit death’s overbearing interruption of our social intercourse gives the psychic his victim, and the theme of conversations with the dead in literature is as old as Homer, and probably much older.

One of the most charming examples of this innocent literary genre is a book we recently obtained from under a pile in a very messy second hand bookstore: Van Loon’s Lives by Hendrik Willem van Loon.

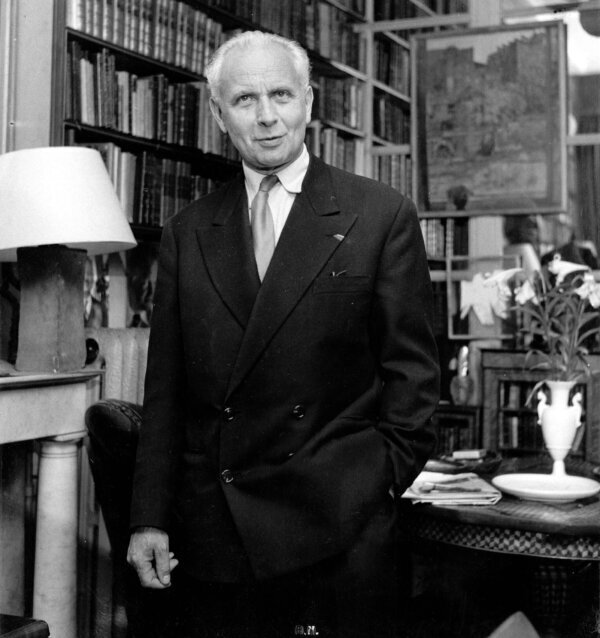

Van Loon (1882 to 1944) was born in the Netherlands, emigrated to the United States in 1902 and became a professor of history at Cornell. He made his mark however, as the author of a long series of popular works, including The Story of Mankind, which won the first Newbery award in 1922. He sold a lot books, for he wrote well and with a generous spirit. He is now forgotten.

The premise of Van Loon’s Lives (he pronounced it Van Loan, by the way) is this: Van Loon, writing from 1942, looks back to 1929, when he and his family were living in the provincial town Nieuw Veere in the Netherlands. A close friend and he decide that what they need in this isolated burg is some dinner company, and they decide to invite Erasmus. Yes, that Erasmus. And Erasmus arrives.

In fact, Erasmus has such a good time at dinner that he takes a sabbatical from the afterworld and moves into town. He then acts as mentors to the friends as they arrange a long series of dinner parties with very mixed company.

The guests, usually but not always two at a time, include, among others:

William the Silent and General George Washington;

Descartes and Emerson;

Robespierre and Torquemada (not a successful evening);

The Greatest Inventor of All;

Plato and Confucius (Confucius brings his grandson in the 42nd degree to translate);

Emily Dickinson and Frederic Chopin.

There are lively incidents.

Torquemada figures he could keep forty prisoners in our friends’ cellar; Benjamin Franklin wants to dry it out.

Erasmus, as a surprise for his friends, invites the Bach and Breughel families and the whole village enjoys a jam session and a sketching party fuelled by sausage, sauerkraut and beer.

Napoleon demands an invitation, and his reluctant hosts plan a dinner party with everything the Emperor hates.

This sounds like fun, and so it is. Still, the book takes some getting used to. The sections on the dinners themselves are relatively short. Most of the book is taken up with preparations for the dinner parties (what to serve their guests is a constant problem) and with fairly long historical essays by Van Loon (the pretext is that these are research to fill in his friend on the background of the guests) and the essays are a little slow and very opinionated.

Modern taste, I think, asks for something less discursive and more dramatic. And yet, given patience, and a willingness to accept the book on its own standards, the book, old-fashioned as it is in style, becomes increasingly charming and unexpectedly moving.

Especially tinged with melancholy is a Saint Nikolaas party for the lost children of history (the princes in the tower; the dauphin; Virginia Dare; the Hamelin children; the child crusaders). Our opening quotation describes the reaction of the children of the village to the marks of suffering in the faces of the guests.

And it is after one has completed reading the series that the point of the long interruptions becomes clearer. Van Loon’s concern is not their time (Plato’s, Dickinson’s, Thomas Jefferson’s) but his own, 1929 and 1942.

The author looks from 1942, and times of catastrophe, back to times of threat. As the dinner parties are planned and carried out, the clouds in the background, mentioned in passing, become darker and darker. As the last dinner party is planned, Hitler becomes chancellor of Germany and the author and his friend make plans to flee.

Now the point of the long discursions becomes clearer. We begin to see that each guest is a representative of past times of trouble, and that their historical backgrounds bear on the growing present peril. As for the historical essays, these too are of their time, for Van Loon was a popular writer, and writing for a people for the most part not blessed with advanced education or easy access to historical information. There was no looking up people on Wiki in 1942.

In as far as the structure of the book looks from one time to another, Van Loon’s Lives is oddly reminiscent of the greatest of all imagined dinner parties, the Symposium of Plato.

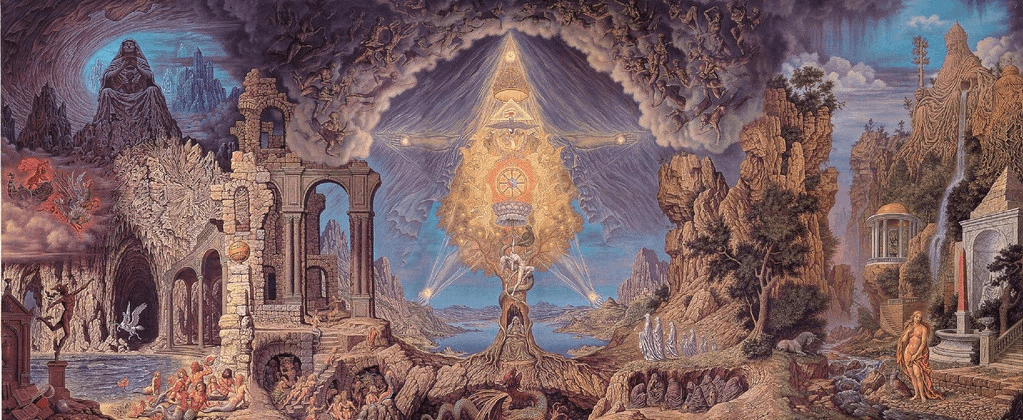

The Symposium is called a dialogue, but it has elements of a ghost story. That story, too, is narrated through layers of memory from a time before catastrophe. In fact, most of the dialogues of Plato have this flavour. It may be that something of this sort, a distancing, is necessary for a successful attempt at this genre.

Eric Voegelin thought it necessary for a successful dialogue that one of the speakers should be divine. The divine and the dead are not the same, but when they speak to us, there is implied in conversations between the living and the dead an assumption that the dead step out of a continuity that underlies our history into the movement of our time. To meet them with equity we must become to a degree ghosts ourselves. Moreover, this works to achieve the absolute necessity of any great work of art, that it should in some way unsettle us, and get under our skin. The edge of sadness and the flavour of strangeness in Van Loon’s Lives is one of the ingredients that has kept it alive in the memory of those who know this work.