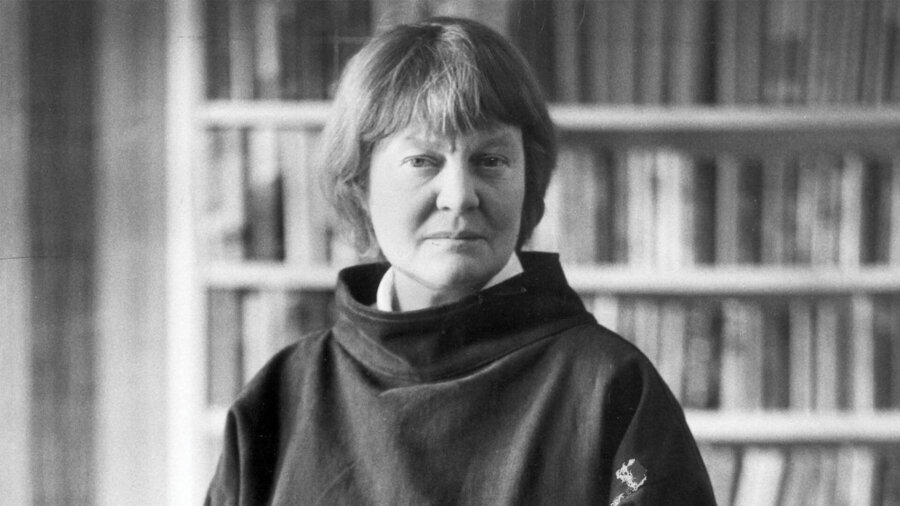

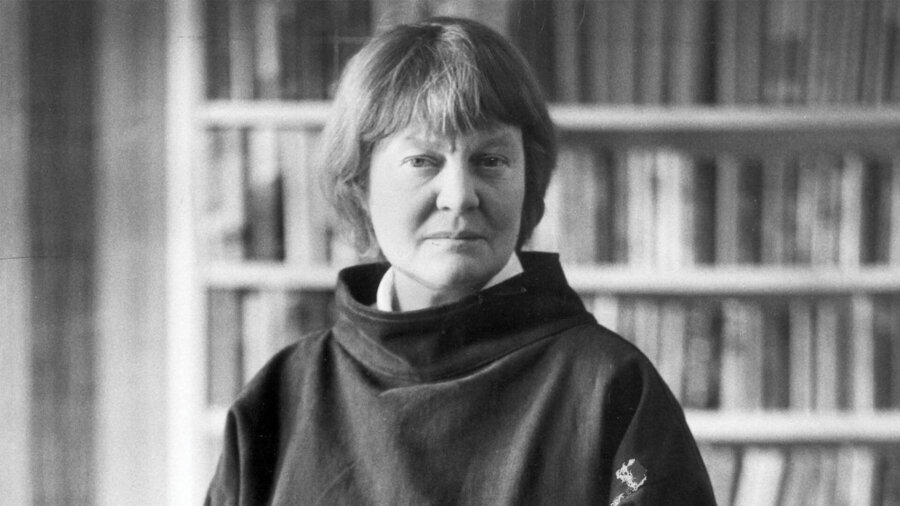

When Jerry and I fly to California for another round of my neuropathy treatments, we each bring something to read en route. Obviously our selections have to be in paperback and short. Since I’d become curious to know more about the four women philosophers – Iris Murdoch, Philippa Foot, Elizabeth Anscombe, and Mary Midgley – whom I’ve recently written about here, my airplane book was Iris Murdoch’s Sovereignty of Good.

Each of these women brought to philosophy a refreshed awareness of what real people go through day by day and over the course of time. Their pathbreaking had drama because, when they first began to write and speak, philosophers in the English-speaking world were especially keen to get rid of all that they deemed “nonsense” – which is to say any assertions not backed by sense perception or else not following validly from their premisses.

This swinging scythe had been brought over from Vienna and popularized by A. J. Ayer, in his 1936 bestseller, Language, Truth and Logic. As a method for avoiding what it called nonsense, it had the name of “logical positivism.”

Much of our lives could be cut down as “nonsense” if approached that way. That includes serious stuff: like whatever you might regret on your deathbed or the one good deed that, dying, you might take to redeem an otherwise misspent life.

Since what I am calling “the scythe” was still swinging when I was a grad student, to face it down took more grit than I had. Its adherents would swing at any utterance that failed to meet its criteria by asking, with long-drawn-out puzzlement, What do you mean? Since people ordinarily draw on a whole background of assumptions, habits, and memories when they say anything, it’s easy to produce stupefaction by lifting a single utterance out of its human context and demanding that the speaker justify it alone.

Here it might be of interest to say a word about Ayer, the man who made this way of doing philosophy widely accepted in the mid-twentieth century. Toward the end of his life, funnily enough, he had a near-death-experience during which, – as he confided to his doctor – he “saw God.” Not only that, but he had the hardihood to describe certain features of his experience (not the seeing-God part) in London’s widely-read Sunday Telegraph, in an article he called “That Undiscovered Country” but the editor retitled, “What I saw when I was dead.” The philosophers I knew all shook their heads, agreeing that “Freddie had lost his cool.” I’m the only one I know of who took his about-face to be brave and philosophically consequential. I even published an article “What Ayer Saw When He Was Dead,” in the October 2004 issue of Philosophy: The Journal of the Royal Institute of Philosophy, spelling out why I thought this.

But all that lay far in the future. Meanwhile, the four women philosophers were pioneering the effort to bring the human story back into the arena of philosophic consideration.

Murdoch is better known as a novelist but, up till now, I’d never felt drawn to her literary output. Her best-known novel has the title A Severed Head (1961), which may explain my reluctance to read her. I like novels and films where we get at least the possibility of a happy ending! Now, despite its awful title, I’m more curious to read it.

In The Sovereignty of Good (1970), Murdoch’s opening essay, “The Idea of Perfection,” strikes me as the most realized of the three essays in that collection. Here she is trying to give an idea of what’s going on when we choose to act morally.

When philosophers write, they often have an opponent in mind. The contest frames the discussion. Murdoch’s opponents – whom she calls “existentialist” even when they’re British – all suppose that we do have freedom of the will, but that our freedom operates in a vacuum. Nothing informs or justifies our most telling moral choices. We just decide.

Murdoch argues that moral conduct isn’t like that. Rather, it’s a response to what we come to see and know over a period of time. As we approach the action point, two features come into focus: what’s at stake in the situation and what we can contribute to it.

Only one act survives this reflective process: the one that’s the best I can do in that context. (This processing can happen rapidly, as sometimes it must, but it is still a process of seeing and knowing.) Therefore, moral choice is not arbitrary willing. It is not vague. It is not approximative or blurry. The right act will be, as Aristotle says, like the arrow winged to its target.

Just as the right word cannot be replaced by a different word, the right brushstroke must put the color just so, the right note must sound on the beat – so the act called for here and now is the one that I must do.

What Murdoch has noticed about moral choice – and splendidly underscored – is this dramatic and complex fusion of discrete elements which could be summed up as follows: seeing what’s at stake, reviewing the relevant experiential layers, figuring out whether this one “has my name on it.” I don’t know of any other recent philosopher who has done this.