Is Life Worth Living?

Faith and Hope

Discerning the nature of ultimate reality is a matter of intuition.[1] A religious experience, for instance, needs to be interpreted and understood by the experiencer. Whether an experience is going to count as genuine or not is up to the person. And then, even if deemed veridical, it is necessary to decide what it means. For those lacking such experiences they are relying on someone else’s assessment and of course that assessment of his assessment might be wrong. Infallible arbiters we are not. Coming to know important epistemically foundational truths is a creative process and those truths remain debatable. For instance, a student reported in class that his hospitalized grandmother told his mother that she, the grandmother, had been visited by a deceased relative who reassured her that though the grandmother was dying everything was going to be okay and that her loved ones were waiting for her in heaven. In the same class, a student who had been a long-term hospice worker commented on how common it was for lucid patients to have conversations with deceased people invisible to the nurses – though, in fact, there are also reports of some of these visitors in fact being visible to others. A boy dying of thirst and heat in the Mojave desert, due to his mother following incorrect GPS directions, so-called “death by GPS,” told his mother that his dead grandfather was speaking to him from heaven, and a lady was reading a story to him.[2] Stories of such comforting reassurances are extremely common. In the news article, pertinently, the boy is described as “delirious and confused.” That is one interpretation of the event, predicated on religious skepticism.

To live our lives, we do not have any choice but to make certain unprovable assumptions – to rely on first principles. Demonstrations and proofs of any kind always rely on unprovable axioms.

We have to make certain decisions about the purpose of life, whether we have free will or not, whether morality exists, what a good life might look like, does God exist, might we be living in a Gnostic universe built by an evil demon, a computer simulation, etc. The most basic decision it is necessary to make is whether life is worth living or not and thus whether it is worth your while to get out of bed in the morning. In this matter, we vote with our feet. In continuing to live and do things the decision has already been made in an act of faith and hope.

Truth is created through subjective, interior experience, and intuition. Einstein developed the theory of relativity through a tremendous act of imagination and creative insight. Almost no one could understand it at first. Those who succeeded in comprehending the theory had to fundamentally reshape their ways of looking at things.

Physical reality, of course, is just a tiny part of what is. Man is a microcosm. To understand all of reality, to the degree that we can, we must try to understand ourselves and our relationship with divinity. To evaluate someone’s point of view, have the person start describing human life – probably any aspect of it, and see how he does. If it is compatible with the insights of Shakespeare or Dostoevsky and sits comfortably with their respective visions then the point of view is rich and good. Another good rule of thumb is that the lower never gives rise to the higher. The opposite is true. The higher gives rise to the lower. A bunch of neurons is not giving rise to the sublimity of the starry heavens at night. The sublimity is confronting the viewer, if he has the heart, mind, and will to see at that moment.

Listening to materialists trying to discuss human life can be a frustrating experience. Some of them can come across as having the emotional maturity of a seven year old; as someone yet to experience the complexity and depth of adult life. An autistic statistics professor who was very sweet and naïve once asked a group of us, fellow professors, “When a woman says “Don’t call me, I’ll call you,” is that a good or a bad sign?” He knew he did not know and he intuited that we did. That same professor complained that people compared him to a child, which he was, emotionally – though a very nice, well-intentioned, and harmless child.

Wishful Thinking?

There is a complicated relationship between knowledge of reality and the way we wish reality to be. Aspiration and reality are commingled. If God is good and life is good, then we should wish reality to be just as it is, including the possibility of mundane experience being transformed and transfigured by the noumenal, and for social existence to be less oppressive. Wanting to align one’s desires with the way things are does not mean submission to a static and fixed reality, because reality is in fact dynamic.

There are within us false egos linked to various passions, and the true ego. Telling one from another is no easy matter. In the essay “Why Philosophy is Easy,” Jacob Needleman writes:

In The Guide for the Perplexed (Pt. I, Chap. XXXIV) Maimonides explains why the pursuit of metaphysical knowledge is reserved for the very few, even for them, it must not begin until they have reached fullest maturity. The subject, he says, is difficult, profound, and dangerous. He who seeks this knowledge, which equated with wisdom, must first submit to a long and difficult preparation – mental, moral and physical. Only then can he risk the incomparably more difficult and lengthy ascent to wisdom.

This naturally calls to mind Plato’s plan of education in which the highest pursuit, philosophy, is also to be the last in line. With Plato, as with Maimonides, we read that the direct search for wisdom is to be preceded by a certain training of all the natural faculties of man: the body, the emotions and the intellect.

Plato recommended the study of mathematics for this purpose.

Iris Murdoch writes that learning foreign languages can play a similar role to mathematics. Such learning makes a person submit to an objective reality that is immune to wishful thinking and egoistic desires. Words mean what they mean and the grammar functions the way it does regardless of how one might wish them to be.

I am learning, for instance, Russian, I am confronted by an authoritative structure, which commands my respect. The task is difficult and the goal is distant and perhaps never entirely attainable. My work is a progressive revelation of something which is independently of me. Attention is rewarded by knowledge of reality. Love of Russian leads me away from myself towards something alien to me, something that my consciousness cannot take over, swallow up, deny or make unreal (Murdoch, Existentialists and Mystics, 1997, p. 373)

In learning to deal with true, subjective,[3] spiritual reality, we become more truly ourselves. We must conform to reality while also participating in it creatively.

A Version of Pascal’s Wager

In Pascal’s wager, believing in God is seen as a precondition for eternal life in heaven with a failure to believe leading to eternal damnation if God in fact exists. Therefore, we have everything to gain in believing in God and obtaining eternal life and nothing much to lose if we are wrong that God exists. Conversely, being right that God does not exist has no real upside, but being wrong exposes one to the worst possible outcome; eternal damnation. Since eternal damnation for any reason, let alone merely believing or not believing something, makes no sense, and represents an all too human desire for vengeance, and a violation of our faith that redemption is always possible, then Pascal’s Wager is otiose.

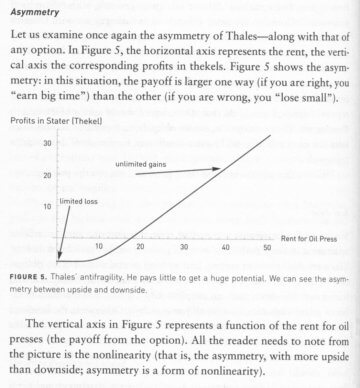

An updated wager that has similar existential implications could concern whether life is worth living or not. For every aspect of life that seems to make life worth living, it is possible to find its opposing mate; for every item like family, health, hope, love, friendship, good books, movies, and music one can oppose horrible families, sickness, despair, hatred, enemies, and bad books, movies, and music. Rationally, the situation seems to be a stalemate. However, the concept of optionality can help us here as seen in Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s book Antifragile. Optionality is Taleb’s suggestion about how to act rationally in conditions of uncertainty. Positive optionality involves exposing oneself to large possible upsides with little downside. In surgery for life-threatening cancer one has much to gain and little to lose. Taking Vioxx for a headache is negative optionality – little to gain, a reduction of relatively minor pain, and much to lose; heart valve damage.

The four possibilities are;

- Life is worth living – right

- Life is worth living – wrong

- Life is not worth living – right

- Life is not worth living – wrong.

If you choose “life is worth living” and you are right, then this would be the equivalent of Pascal’s believing in God and going to heaven. You will live your life believing it to be good and beautiful. You will love and learn, have friends, engage in projects, live a hopefully fulfilling life and die. Best of all, your assumption will be right. It has a massive upside.

If you choose “life is worth living” and you are wrong, you will do all of the above, falsely thinking that love and friendship, health and joy, goals and family are good and beautiful, and then dying, is not good, but it does not seem too bad either. The downside seems minor, whereas being right that life is not worth living does not seem to have any real upside. Someone could perhaps take some dour satisfaction in being right before killing himself to put an end to the pointless misery.

And thinking that life is not worth living and being wrong would be the equivalent of eternity in hell in Pascal’s thinking. Someone would have wasted his life, missing out on everything good or failing to appreciate it. He will have thrown his life away and lost everything. The downside of that bet would be the worst possible outcome.

So, optionality says that rationally, we should bet that life is worth living. There is little to lose and everything to gain. By still being alive and bothering to read this, you have made this bet anyway.

Below is a graph, from Taleb, showing asymmetry of outcomes and optionality.

The trouble with even an updated version of Pascal’s wager is that it seems rather thin gruel, relying as it does fairly exclusively on rationality, and thus the intellect. Perhaps the most favorable interpretation of it could be that even rationalism suggests making a leap of faith. Rationalism, in this case, points to something beyond itself. Yet, in order to fruitfully commit oneself to life someone’s emotions and will must come along for the ride, and the updated Pascal’s wager seems unlikely to achieve this.

Perhaps the argument could be a starting point to finding a proper reason for living that will involve love. Love of people, love of God, and love of some ongoing projects, and the faith that all those things are worth it.

Looking for a Way Forward

If a philosophy or metaphysical assumption leads to a dead end; that would make life pointless, then another assumption should be made and another philosophy adopted. Look for the exit and follow your nose. The philosophy of Mircea Eliade in The Sacred and the Profane, for instance, contrasts “religious man” with “secular man,” and suggests that the only meaningful life is the life of religious man, but then suggests that being religious man is no longer possible. If that is the case, then suicide seems apropos. At that point, start looking for the exit – for a door to another outcome. Such a philosophy is a wrong turn and another way to one’s destination must be found – that destination being a life as good and meaningful as possible.

If truth must be created, then nihilism points to a false ego and a deafness to the nihilist’s spiritual core. Nihilism posits that all paths are dead ends and no positive exit is possible. Since metaphysical truths are not provable, the young nihilist cannot really claim that he has proven himself to be right. It is posturing; wanting to be admired for being so hard core; so brave in facing the truth of nihilism, so careless of his own happiness (and ours), pursuing truth even to the most horrible of outcomes. But really, he has just embraced despair, which is far from heroic.

Contradictions of the Nihilist

Instead of killing himself, the nihilist wants our admiration while he continues to say how pointless it all is. In their earnest way, young nihilists continue to think that it is meaningful to persuade us that life is not meaningful. In fact, they will make it their life’s mission to convince the unpersuaded which they will regard as a worthwhile and meaningful enterprise. Their putative love of truth contradicts their nihilism. They do not regard the pursuit of truth as a stupid and pointless thing; in fact, they consider it good. Hence they are committed to the good and the true.

Nihilism and materialism are assumptions congenial to each other. Certain people seem to think that materialism has been proven to be true. Not so. It is simply a common assumption. The relation between mind and body remains an open question.

Some nihilists contend that we live in a loveless universe that is indifferent to human existence. It is a strange claim, contrary to the facts. Perhaps, it stems from a rhetorical tendency to make a firm distinction between humanity and the universe. But, human beings are part of the universe too. Physically, we are made from stardust, and we can be thought of as the universe becoming self-aware, and turning around and studying itself. Not every part of the universe needs to be conscious for the universe to reach self-consciousness, and not every part of the universe needs to love humanity in order for humanity to experience love, and be loved. Every human being in existence is evidence that love exists and that that person was loved; at least enough to stay alive and not to experience attachment disorder. With food and warmth, but without love and with extreme neglect, as usually only happens in very crowded, badly run, orphanages, a large percentage (30-40%) of babies will drop dead, and those who survive can develop attachment disorder. Attachment disorder renders children similar to sociopaths in their inability to love or to form positive social connections. Ceaușescu,[4] the Romanian dictator, made both birth control and abortion illegal; resulting in thousands of abandoned children in orphanages. Some Americans adopted these children, only to find that their baby had attachment disorder who, when it grew a bit older, would try to strangle other children in their sleep, or throw kittens out windows to their deaths, and who would ignore any attempt to interact with them socially. Sociopaths, conversely, are frequently very charming and engaging and exert a strange fascination for others – though they exhibit the same amoral and sometimes sadistic tendencies. Any person who is alive and does not have attachment disorder has experienced some minimal level of love. Babies are very challenging to look after, it is a very emotionally demanding task, and parents have to make great efforts.

Humans most want and need human love, and that is what most of us get – though sometimes not as much as we would like, and as imperfect as that love, and expressions of that love, can be. Ideally, the universe would provide two agents whose special task it is to take a special interest in you as an individual; to tend, love and feed us as babies; show care and concern for our upbringing, and to do their best to usher us into the world in such a manner that we have the best chances of flourishing. These agents exist and are called “parents.” We may be waiting for the moon to wink at us, or wish that alien races on Alpha Centauri would send a text message, but some local source of benevolence would be best – where it could do us the most good. Actual human love is optimal partly because this is what we long for most and partly because it is the most practical when we are helpless infants. Humans, mostly, know how to look after other humans.

So, people who make the “loveless, indifferent universe” claim seem similar to the famous parable of the man who is told that “God will provide” and who, in order to escape a flood, consequently rejects the offer of a car ride, a boat ride, and finally help from a helicopter, saying in his refusal in each case, “God will provide.” He subsequently drowns. When he quizzes God in heaven as to His failure to provide, God replies that He sent a car, then a boat, and then a helicopter but was rejected in each case. If God were to provide, He would need to do so using some specific method; making use of the means available. And nature, and “the universe,” provide parents for most of us. The same goes for many animals. I sometimes imagine a kitten thinking “Oh, my god, Mom’s a cat.” But, actually, cat mom’s tend to be perfectly loving and capable and kittens are generally in good hands (paws.)

Other Unprovable Metaphysical Commitments

Does God exist?

If the universe exists because of God and God is good, then the universe will exist for a purpose and that purpose will be good. Life can be counted on to be meaningful and scientists can continue to hope that the order of the universe may be discoverable. So, I choose YES, God exists.

Does free will exist?

YES. Without free will, persuasion would be impossible – only causation would exist. So, no one can persuade me that free will does not exist. Also, existentially, I would effectively be nothing but a mechanistic robot doing what I have been pre-programmed to do. My choices would be meaningless. I could neither be praised nor blamed for anything I do and my entire existence would be pointless. Determinism is a despairing hell.

Does morality exist?

YES. I have experienced moral guilt as has every non-psychopath on the planet and thus have direct evidence that morality exists. I believe in fairness and justice, love and mercy, as does every non-psychopath. I believe in these things because I have witnessed them and have no convincing reasons for thinking my experiences are illusory. In addition, choosing this option makes life more beautiful and meaningful. I would not want to live in a universe where being a psychopathic murderer was not a bad thing or where being mean was on a moral par with being kind.

Iris Murdoch would have liked to believe in God but, possibly because of her cultural context, considered it no longer to be a live option. My experience thinking about such things indicates that an atheistic non-nihilist decision-tree does not exist. Fortunately, theism remains a live option for many of us. God has not been proven not to exist or to be an absurdity and there is no contradiction involved in believing in God.

Thomas Nagel has said that he would not want to live in a universe with a God in it. His response to an email asking him about this was “I have nothing more to say on the matter.” So, some people do not see a belief in God as life-affirming.

One gets the impression that people tend to have a gut-feeling one way or the other and then choose their reasons for believing or not believing following their respective intuitions. Some seem not to find the idea of God beautiful. Maybe they simply find that they cannot believe, a terrible state of affairs, limiting their options.

Sometimes people have a moral objection to the existence of God. Since the existence of morals presupposes the existence of God the argument fails. Additionally, there are plenty of wrong ideas about God to criticize. The atheist is really just doing theology without realizing it.

Final Comment

Keep choosing metaphysical commitments that you find to be life-affirming – that seem to offer the promise of leading you on and helping you to feel that you are moving forward towards some positive goal, and especially that positive goals exist. If you find a door shutting in your face and no exit appears in front of you, try making a different commitment. Despair is a permanent human possibility, but it is not a necessary one. If you keep looking, with a bit of luck, you will find a way. Matthew 7:7 “Ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you.”

Notes

[1] Axioms in a science as precise as mathematics are, by definition, also unprovable. Multiplication, for instance, relies on nine unprovable axioms to work, the exact number depending on how the axioms are formulated. An example is P = P. And Goedel’s Theorem proves mathematics above the level of complexity of simple addition generates “Goedelian propositions” that are true, but also unprovable within the axiomatic system. Nonetheless, their truth is evident to mathematicians; intuitively, directly, perceived. That is why mathematics as a science cannot be automated. No axiomatic system, above a minimal level of complexity, can be both consistent and complete. The halting problem – the impossibility of having an algorithm for testing whether all other algorithms are valid (lead to a legitimate result) – proves the same thing.

[2] https://www.sacbee.com/entertainment/living/travel/article2573180.html

[3] The usual subjective/objective distinction is derived from materialism. If spiritual reality is primary, as Plato and Berdyaev thought, and this reality is found in interiors, then the “objective” is derived from the “subjective” and represents a lower level.

[4] Pronounced “chow-chess-queue.”