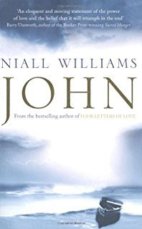

John: A Novel

John: A Novel. Niall Williams. New York: Bloomsbury USA. 2008.

“The question came to me out of the blue,” Irish writer Niall Williams writes. “What was John doing the day before he wrote the gospel?” Williams’s answer has produced arguably one of the most satisfying novels since Flannery O’Connor scribbled her “grotesqueries” on her front porch at Andalusia.

The book is both stark and explicit, reminiscent of Hemingway’s best prose, and presents its story in what French critics describe as a mise en abîme, a “casting into the abyss . . . successive, perhaps concentric, layers of space as analogous to the various strata of experience that are constitutive of mystical space.” It reveals “God is both ‘enclosed’ within the mystical soul, and he is the ‘enclosure’ that the mystic enters spiritually.”

The story begins on the bleak and barren isle of Patmos where the now ancient John (The Apostle, the son of Zebedee, the brother of James) and a handful of his disciples have been exiled by the Roman Emperor Nerva. Christianity finds itself in reduced circumstances, its more vociferous advocates decorating the various Roman roadways throughout the empire, and its teachings competing with a plethora of demonic distortions.

John’s disciples wait. He has not preached in a long time, he is blind and crippled with great age, cared for by the devoted Papias, his “Revelation” long since recorded by the scribe Prochorus. Their faith has reduced itself to the promised return of Jesus Christ, but He has not appeared. One of John’s younger followers, Matthias, proposes what we would today call a sort of Arianism: “The Son of God would not play with children, would not learn the trade of carpentry. For what?. . . The truth is, Jesus was as you or I.”

Williams has set his story at a time when the phenomenon of the “Christ event” is neither doctrine nor dogma, but rather an accounting of a recent experience, when reality is understood in the “fullness of Passion and Resurrection.” John is the living testament, the last of the disciples of Jesus Christ. He has loved and been loved by the Christ, the Son of the living God.

Yet, even now, with the scribes’ ink barely dry on the pages of the Gospels, there rises the skeptic. Faith is immersed in doubt. The scribe Prochorus has fallen ill. John seeks his healing: “He prays in silence, moves slightly back and forth on the stool so its joints sing thinly. And still nothing happens. How often is it to be so? To the ten thousand prayers they pray these years on the island what answers come? No miracles attend them. No signs that they are cherished, or that the long suffering of their faith is considered, that their sacrifice is measured and in the hereafter will be rewarded.”

Williams’s novel is not only art, in the sense of his mastery of prose, his formidable moral imagination, and his talents as a storyteller, but it is also an expression of his profound wisdom in understanding that our purpose as existent and created beings is to live in the love of the Creator.