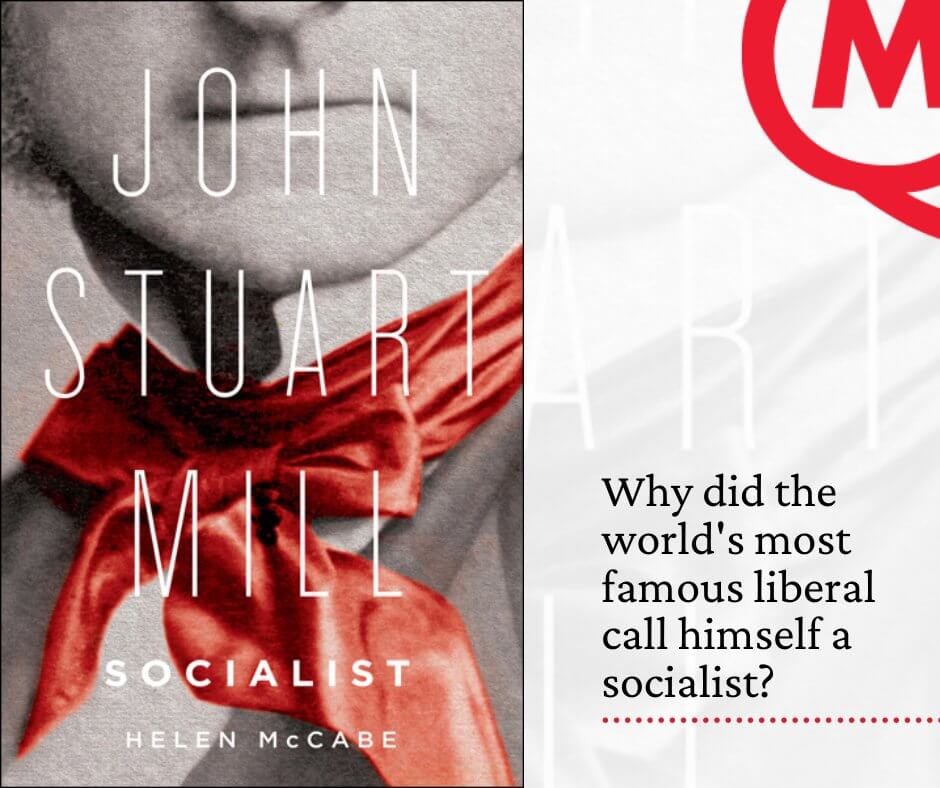

John Stuart Mill, Socialist

John Stuart Mill, Socialist. Helen McCabe. Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021.

Helen McCabe states that the primary goal of John Stuart Mill, Socialist is to demonstrate that Mill’s self-characterization of his views as “socialist” should be taken seriously and literally. Contrary to entrenched views of Mill as a major representative of classical liberalism and/or a libertarian advocate for individual freedom, she argues that Mill, as he himself claims in the Autobiography, is most accurately categorized as a Socialist.[1] A secondary aim of the book is “to introduce [readers] to a vision of the future that has much to recommend it. . .” (268). The author seeks to enlist Mill in the contemporary cause of socialism by uniting his putative “liberalism” with his “socialism.” She clearly assumes that such a cause will be strengthened by demonstrating Mill’s commitments to socialist ideology; the tone of the work is self-congratulatory and even triumphant. Be that as it may, she is undoubtedly correct in perceiving such a unity. The author’s central thesis is correct—Mill was deeply enamored of socialism and socialist aspirations and values shaped his views in a significant and enduring manner. Her book serves as a much-needed corrective to what can only be called Millian mythology.

The work is divided into five chapters: Mill’s early influences; his criticisms of private property and capitalism and of contemporary socialism; Mill’s socialist principles; and his “utopian’ vision of an ideal society. McCabe begins by identifying the chief influences that led Mill to his ultimate advocacy of a “qualified’ socialist ideal. These stem largely from the young Mill’s encounter with French socialism, including and especially the St. Simonians and Auguste Comte. She highlights the two chief St. Simonian concepts that would permanently shape Mill’s vision of socialism: the St. Simonian philosophy of history and the belief that one of the alleged ‘laws’ of economics (the so-called “law of distribution”) was not in fact an immutable law but rather a product of human construction and thus amenable to change.

The St. Simonians conceived history as developing in line with a series of alternating “organic” and “critical” periods, which engendered the conviction that all existing social institutions were merely provisional stages in the path of history towards its “final age.” Those familiar with Eric Voegelin will recognize the secularization of the “three-stage” theory first elaborated by Joachim of Fiora in the twelfth-century and evident in the thought of various eighteenth- and nineteenth-century thinkers. Mill embraced a version of such theory throughout his life, regarding his own era as a “transitional” “critical” stage on the verge of initiating a new and improved “organic age.” Such a view was central to his embrace of socialism, since it led to his conviction that all existing institutions, including capitalism and individual private property, were merely provisional stages in the movement toward the ultimate and ideal society, in Mill’s case, a “distinctive and unique” version of socialism.

The other St. Simonian concept that shaped Mill’s embrace of socialism, as said, was the denial of the immutability of the so-called economic “law of distribution.” The distribution of the fruits of production, unlike the immutable “law of production,” was said to be susceptible to social construction on the basis of human will and preference, opening up vast possibilities for increasing human happiness. Under contemporary capitalist economic arrangements, the alleged “law of distribution” resulted in an unequal distribution of material wealth. Such inequality, Mill came to believe, was inimical to human happiness and also unjust in significant ways. Such injustice was significantly related to existing and previous laws of inheritance and the more or less forced labor of workers who themselves owned no capital. While Mill himself does not employ the term “wage slave,” he, like Marx and other socialists of the era, came to see workers as fundamentally oppressed by capitalist owners of the means of production, as well as the land-owning aristocracy. Mill’s movement toward socialism was impelled by his demand for a “higher justice”— “social justice” —which he believed was embodied in the socialist ideal.

McCabe does not attempt to attempt to evaluate the validity of Mill’s claim that the “law of distribution” is strictly a matter of human construction and preference. The fact that he embraced such a view is offered as seemingly prima facie evidence of its truth. As we shall see, this is a flaw that saturates the book as a whole. There is little to no attempt to evaluate the truth or soundness of Mill’s convictions, which rather are generally presented as if they are statements of fact, more or less beyond criticism.

*

According to McCabe, Mill held utility, defined as the maximization of human happiness, as a core principle that was informed by other principles including security, progress, liberty, equality, and fraternity. The effort to balance such value commitments, she argues, explains Mill’s ultimate preference for socialist institutions insofar as he came to believe that only a “qualified” form of socialism . . . will achieve the greatest happiness of the greatest number” (18).

McCabe offers considerable textual evidence of Mill’s hostile critique of the laissez-faire doctrine prevalent in his time, which supported individual private property and a government limited to the prohibition of force, fraud, and theft and the enforcement of contract. He criticized such a “night-watchman” view of government for limiting government to the protection of rights of person and property and regarding government as more or less a “necessary evil.” He himself envisioned a more ambitious and positive role for government; its purpose is not limited to the protection of negative rights but should rather involve the “improvement of mankind.” The pursuit not only of utility, but also of security, progress, liberty, equality, and fraternity, demanded a change of existing institutions, including and especially the laws governing inheritance and the regime of private property. The author further explains that Mill’s famous defense of individual liberty in On Liberty should not be confused with the doctrine of laissez-faire. On Liberty advocates for extensive individual liberty with respect to self-regarding actions, but, as she notes, Mill regarded “trade [as] a social act” which thus falls within a different sphere (45). Nor should Mill’s defense of liberty be thought to conflict with his socialist vision. McCabe argues that, for Mill, liberty is more or less synonymous with autonomy or sovereignty. Workers under capitalism are inevitably dependent on capitalists, and thus unfree, not autonomous or sovereign rulers of their own experience, which impedes the development of their individuality. Their freedom thus requires the attenuation or elimination of individual private property and the achievement of democratic control by workers over the means of production, discussed more fully below.

McCabe is concerned to challenge the received view of Mill as a “liberal” reformer who sought simply to improve and not replace existing institutions. Her argument is that those who view Mill in that light fail to recognize the significance of the broader philosophical and historical framework that informed his views over the decades. As mentioned, under the influence of the St. Simonians, he concluded that all existing institutions and values (including liberty and individual property rights) were merely provisional, destined in the future to be replaced by “something better.” Mill never advocated violent revolution nor did he subscribe wholeheartedly to any of the existing socialist movements of his era. He rather developed his own view of the manner in which present capitalist institutions and values might be transformed by means of gradual and piecemeal evolution away from capitalism and toward the higher ideal of socialism, the “North Star,” as Mill put it, that should guide all efforts at reform. His defense of various capitalist institutions, including his well-known defense of competition, McCabe argues, must be viewed in that light. When Mill says that “laissez-faire should be the general rule” he means “for now” and in the present state of social circumstances and human nature. Both elements, however, are in a state of transition toward “something better.” He supported the “regime of individual property, not as it is, but as it might be made” (52).

Mill criticized contemporary capitalism on various grounds: efficiency and waste; liberty and individuality; and equality and justice. The inefficiency arose, Mill said, insofar as “. . . society’s unproductive labour [distributors or middlemen] . . . [was] devoted to . . . objects [of] little worth.” Liberty and individuality were suppressed insofar as laborers had little choice of occupation or freedom of movement; indeed, half the human race was bound in “entire domestic subjection.” Mill, like Marx, also condemned capitalism on the grounds of equality and justice. Capitalist distribution, wrote Mill, cannot be morally justified: “attempts . . . to defend private property on the ground of justice must inevitably fail [because] the distinction between rich and poor, so slightly connected as it is with merit and demerit, or even with exertion and want of exertion in the individual is obviously unjust.” Throughout his life, Mill yearned for a desert-based justice, which of course is impossible to achieve in a market-based economy. He further believed it was unjust that “some are born to riches and the vast majority to poverty”; that some people were “exempt from bearing the share of the necessary labours of human life” without having “fairly earned rest by previous toil”; and that remuneration was so unequally apportioned, “. . . almost in an inverse ratio to labour. . . . ” Accidents of birth played a large role in contributing to such “prodigious inequality,” such injustice. (52—53).

Mill also criticized capitalist society for its inability or unwillingness to secure subsistence for all persons. Such insecurity of material provision led to a kind of “dog-eat-dog” social ethos where people had to claw their way to the top. The lack of “equality of opportunity,” in contemporary language, created an unlevel playing field, preventing “all from starting fair in the race.” Moreover, Mill was a proto-environmentalist in certain respects, condemning the destruction of untouched nature under the jaws of modern capitalist technology and its underlying values. Even more, as said, he condemned what he regarded as the “social ethos’ prevailing in capitalist society: the endless “struggling to get on . . . [by] trampling, crushing, elbowing and treading on each other’s heels which forms the existing type of our social life.” It would be much better if “while no one is poor, no one desires to be richer, . . . [if] there is a well-paid and affluent body of labourers [but] no enormous fortunes.” Mill also criticized what he regarded as the capitalist obsession with the pursuit of growth—increases in wealth and productivity—the metric of success, he believed, by which capitalist societies measure themselves. He concluded that society needs, not “increased production [but] a better distribution.” Capitalism was also denigrated for preventing the development of the all-important “social feeling”— “fellow-feeling and community of interest”—among all members of society. He too wished that “cash-payment should no longer be the universal means between man and man.” Contemporary capitalism was focused on the wrong thing—material wealth for a few—and it fostered the wrong kind of relations among people: competing and conflicting interests and a willingness to “elbow” others out of the way for personal gain. He concluded that in comparing socialism and capitalism, we ought to consider “not contemporary capitalism [but] the regime of individual property . . . as it might be made” (54-56).

The various criticisms of capitalism and individual private property made by Mill throughout the years stem mainly from his animus toward what he terms “unearned” wealth—chiefly wealth earned by inheritance rather than “personal exertion.” He has the traditional British aristocracy in mind, along with “middlemen” or “distributors” operating within the regime of individual private property. The existing distribution of wealth, he believed, arose from centuries of injustice and cannot be justified on moral grounds. Moreover, it creates unfair advantage in the “race” of life. Indeed, as noted, he complains that the least desirable and most strenuous work often receives the lowest financial remuneration while the leisured class, who may not expend any effort whatsoever, receive a lion’s share of society’s wealth; such a distribution, he believes, is transparently unjust. The regime of individual private property is further criticized for rewarding those who possess natural abilities and talents over those not so endowed by nature. This results in an unequal distribution of wealth, unearned in Mill’s estimation. It is yet another unfair advantage, along with inheritance, achieved not by “personal exertion” but the mere accident of birth.

*

According to McCabe, Mill’s “solution” to the alleged injustices of capitalist methods of production and distribution was the creation of decentralized “co-operative associations,” democratically controlled by their members. He envisions the voluntary pooling of resources by members of such independent cooperatives, who will jointly own and control the capital thus created, democratically electing managers and democratically determining the rules of justice under which the fruits of production will be distributed (which may vary across cooperatives). He envisions a process that over time will lead to the elimination of individual ownership of the means of production and the development of a society constituted by numerous such cooperative associations, both of producers and consumers. All members will not only have ownership and thus control over the means of production (and consumption) but will have a strong interest in the success of their particular cooperative. Such associations will thus prove more productive than capitalist institutions in which workers feel alienated and exploited by the owners of capital and land. Such an outcome, Mill predicts, will lead, through a competitive and voluntary process, to the eventual demise of private ownership by capitalists. Mill also wished to attenuate the laws of inheritance in order to prevent unfair advantages accruing merely to the accident of birth. We have seen that he also regarded natural talents as inherently unjust, providing undeserved and unearned advantage by mere accidents of nature. Such unfair disadvantage might be rectified by the construction of novel laws of distribution, democratically devised by the various cooperative associations. Mill, as mentioned, was also an early proponent of the “no-growth” economic policies of the contemporary Left. He valorized the so-called “stationary state” (wherein, he theorized, the rate of profit has fallen to zero) as beneficial to the cultivation of human values higher and more noble than the vulgar commercial values that allegedly impel capitalism. The absence of a malignant “profit motive” would encourage the cultivation of a higher type of human being than the selfish and ignoble type shaped by capitalist institutions.

All such economic progress, however, depends on even more fundamental progress—the improvement of human nature—particularly the overcoming of human selfishness and the enlargement of human sympathy to include all of humanity. Selfishness, self-interest, greed, materialism, individualism, narrow parochialism, and other such vices must be rooted out and human nature radically transformed. In particular, the “social feelings” must be cultivated. This can be facilitated by the widespread embrace of a novel secular religion—the Religion of Humanity that he absorbed from Comte and fellow travelers—and early education directed toward instilling in every person a desire for “unity with Humanity.” Such moral improvement will take time, perhaps centuries, but Mill has no difficulty conceiving its possibility and desirability.

*

Such is only a small sample of the extensive textual evidence McCabe provides in support of her thesis, namely, that Mill was a Socialist, however “qualified” his particular version, who conceived the achievement of socialist values and institutions as following from a gradual and evolutionary process unfolding over time. One must conclude that McCabe has made her case. Her book is essential reading for anyone who seeks to comprehend Mill’s role in the development of the Anglo-American liberal tradition.

That said, the book is flawed in various respects. First, while the writing is generally clear, the chapters are often repetitive and redundant; the book would benefit from rigorous editing. More important, it is almost devoid of critical or objective analysis. It begs the question of whether socialism is a desirable or workable set of arrangements for a free people. McCabe assumes, without considerable argument or evidence, that it is desirable and workable. She seems oblivious to the scholarly contribution of seminal thinkers who have demonstrated the theoretical flaws of socialist systems, as well as the historical record of societies that have implemented socialist ideals since Mill’s era. Socialism is merely asserted to be the ideal toward which all human beings should strive, and Mill’s authority is harnessed in support of that view. His views are generally presented as authoritative and beyond criticism, although both theory and history suggest otherwise.[2] While the presentation is inherently biased and subjective and, at times, superficial, displaying little insight into the preconditions of human flourishing, McCabe nevertheless succeeds in achieving her main goal: demonstrating that Mill was a truly radical socialist who wished nothing less than an all-encompassing “transformation of society” in accordance with his preferred vision. The “improvement of mankind” is a vast and near-boundless endeavor: Mill sought to transform not only economic arrangements, but also morality, political organization, family; marriage; religion; tradition; and human nature itself. Mill falls squarely in the camp of the ideological dreamers whom Voegelin so deftly dissected.

Perhaps the widespread failure to recognize Mill’s grandiose ideological aims stems in part from his unique position in the liberal tradition. Mill, unlike a Comte or a Marx, was fluent in the language of the liberal tradition and used his knowledge to good purpose, uniting traditional liberal symbols with socialist aspirations. He was a pivotal figure in the transmogrification of the liberal tradition over the course of the nineteenth and following centuries. He had one foot in the classical-liberal tradition and, from time to time, authentically liberal values are supported in his corpus. But, in his most important incarnation, Mill should be recognized as the first “Modern Liberal.” Indeed, McCabe’s case could have been strengthened by tracing the development of “liberalism” as it follows in the wake of Mill, especially in the United States. “Liberalism” in American society has been transformed from its classical advocacy of limited government and inherent rights of person and property into its antithesis, a philosophy of “Big Government” and extensive governmental direction, if not outright control, of the social process. One can clearly see such a development by the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century; L.T. Hobhouse’s Liberalism (1911) is representative. So is the American Progressivism of the era, which would eventually appropriate the time-honored term “liberal” to describe the advocacy of greater governmental direction of the social process. As is increasingly evident in contemporary American society, American “liberalism” and “progressivism” are little more than synonyms for one form or another of socialism, however “qualified.” There is a clear line of evolution from Millian “liberalism” to Fabianism to progressivism to modern liberalism. All such movements envision a greatly expanded role for government in society, typically, like Mill, employing socialistic means toward the end of “improving mankind” in some fashion or other. McCabe is correct: Mill was a “qualified socialist.” But he may just as readily be labeled a modern liberal progressive, and the “liberal” tradition that develops in his wake may just as readily be labeled a type of “qualified socialism,” certainly in the United States. Such a trajectory confirms McCabe’s analysis, and it is odd that she does not emphasize that in her book.

*

We end this review with a rather startling statement by the author which appears in the conclusion of the book and which demonstrates the unbounded scope of modern liberal/progressive/socialist aspirations. It is clear throughout the work that McCabe is herself a radical socialist who seeks the destruction of capitalism and traditional society in all its manifestations. As said, she clearly believes she has won a victory in enlisting Mill in that struggle. Whatever its value in that regard, however, few scholars will deny that Mill’s corpus is marked by a profound sense of moral superiority (if not breathtaking arrogance). McCabe’s concluding remarks betray a similar sense of self-importance: “. . . [W]e [the contemporary radical reformers] are the only people who can, in the end, save humanity and the world in and on which we live. [This] may be a difficult truth to swallow, but that does not make it less true” (169).

McCabe seems oblivious to the devastation wrought by modern ‘secular messiahs’ of all stripes, a phenomenon so brilliantly elucidated by Voegelin. Her book clearly reveals that the ideological impulse that led throughout the twentieth century to the destruction of untold millions of human lives and irreparable harm to millions more is far from dead.

Notes

[1] As he there tells us, “My new tendencies . . . consisted . . ..so far as regards the ultimate prospects of humanity, to a qualified Socialism” (cited in McCabe, 19)

[2]His errors, for instance, are almost too numerous to list. A small sample would include his (false) view of the “law of distribution” and failure to recognize the subjectivity of economic value; his embrace of the St. Simonian philosophy of history; the belief that capitalism is inherently unjust and exploitative; the failure to recognize the benefits of inherited wealth; his belief in the plasticity of human nature; his inability to recognize the dependence of the free society on inherited religious values and tradition more generally, to name only the most obvious.