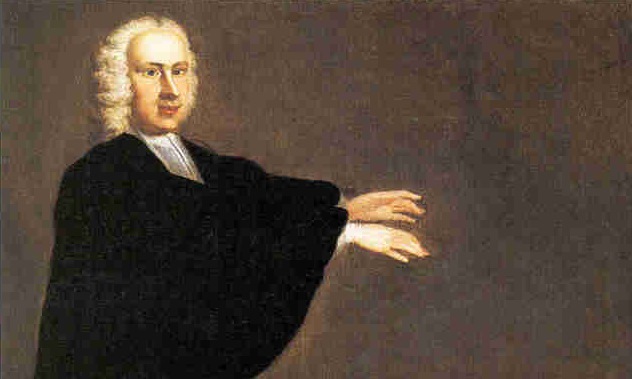

Jonathan Edwards and the Re-Enchantment of the Saeculum: The Puritan and Edwardsian Roots of the Idea of Social Progress

Jonathan Edwards has been called “the American Augustine.”[1] From the threads of introspective piety to the Edwardsian conception of aesthetics, there are strong influences and inheritances from Augustinian philosophy and theology throughout the works of Jonathan Edwards. But in no single area was there a greater, and momentous—indeed, revolutionary—departure from Augustine and Edwards than in their respective philosophies of history. Whereas Augustine envisioned a de-sacralized saeculum of irredeemably mixed plurality: saints and sinners, cupiditas and caritas, wise and unwise, until the Final Judgment which necessitated an agnostic view of History (with regards to “historical and social progress”)[2] that extended to Augustine’s view of the Christian Church in-of-itself (especially concerning his doctrine of the “mixed church”),[3] in History of the Work of Redemption, Edwards re-sacralized the saeculum to provide a re-energized providential reading of History moving to some teleological completion and eventual progress and perfection to society. This change of view has generally characterized the revolutionary and progressivist nature of Protestant historiography,[4] with wide-reaching legacies down to the present day.

William Barret best explained the paradoxes of Protestantism’s relationship with modernity and progressivism:

“At first glance, the spirit of Protestantism would seem to have little to do with that of the New Science…In secular matters, however—and particularly in its relation toward nature—Protestantism fitted in very well with the New Science…With Protestantism begins that long modern struggle, which reaches its culmination in the twentieth century, to strip man naked. To be sure, in all of this the aim was progress.”[5]

The same can be said of American Puritanism and its relationship with modern ideas of progress, progressivism, and revolutionary historicism. While moderns may classify Puritanism as reactionary or conservative, in its time Puritanism was a major departure from inherited orthodoxy and therefore one of the first steps toward revolutionary and progressive philosophy.

After all, Reinhold Niebuhr devoted an entire book on the ironies and paradoxes of American history and the roots of exceptionalism, progressivism, and liberalism all having their genealogical genesis in American Puritanism.[6] David Hume also considered Puritanism to be the first progressive political ideology that resembled a systematic metaphysics than traditional religion (in contrast to Catholicism).[7] Furthermore, Leo Strauss defined the theological roots of secularism by stating, “Secularization means, then, the preservation of thoughts, feelings, and habits of biblical origin after the loss or atrophy of biblical faith.”[8] Likewise, Larry Siedentop has characterized secularism as “the preservation of Christian ontology without its metaphysics of salvation.”[9] To this point, Robert Nisbet reminded readers that “Edwards’s…philosophy of history with its inevitable millenarian outcome cannot be separated from the seventeenth-century Puritan Americans who saw progress as essentially divine.”[10] Even if the latter part of this equation has atrophied in modern society, the relationship between divinity and progress was at the heart of Edwards’s philosophy of history, and at the heart of the notion of Historical Progress in its original inception. To then follow the understanding of secularism in philosophy and sociology as the “preservation of thoughts…of biblical origin after the loss or atrophy of biblical faith” means that modern sensibilities about the history of progress, and social progress more generally, are grounded in deep fideistic roots whether people recognize this or not. Robin Niblett, who was very frank about the role faith in progress has played in the development of liberalism, even wrote, “The liberal international order has always depended on the idea of progress.”[11]

Augustine and the De-Sacralized View of History

There is generally a strong emphasis on “Augustinian strain of piety” in Puritan, and especially Edwardsian, philosophical theology.[12] While this may be true, what is often lost in the claim of the heavy debt that Puritanism, and Edwardsianism, owes to Augustine is the radical break in the philosophy of history between Puritan millenarianism—best reflected in Edwards’s philosophy of history—and Augustinian amillennialism (and his anti-millenarian outlook more generally). Augustine strongly accosted chiliastic Christian outlooks in the fifth century, considering them wrongheaded and dangerous.[13] It is therefore necessary to begin with the general philosophy of history that Edwards is breaking with, which paves the way for what Avihu Zakai called “a new historical consciousness” of “revolutionary character”[14] that will come to define Edwards’s philosophy of history and its inherited legacy and outgrowth.

In his masterpiece, De Civitate Dei (The City of God), Augustine outlined a de-sacralized view of history that he called the saeculum. Reacting against both Pagan claims that Christianity was the catalyst for the Sacking of Rome and Christians who advanced the idea of imperium Christianum, Augustine advances a view of history overwhelmed by libido dominandi—that humans have no role to play in the separating the wheats from tares—and that the ultimate peace and love to be found in God is not to be had in this world:

While this Heavenly City, therefore, is on a pilgrimage in this world, she calls out citizens from all nations and so collects a society of aliens, speaking all languages. She takes no account of any difference in customs, laws, and institutions, by which earthly peace is achieved and preserved – not that she annuls or abolishes any of those, rather, she maintains them and follows them (for whatever divergences there are the diverse nations, those institutions have one single aim – earthly peace), provided that no hindrance is presented thereby to the religion which teaches that the one supreme and true God is to be worshipped. Thus even the Heavenly City in her pilgrimage here on earth makes use of the earthly peace and defends and seeks the compromise between human wills in respect of the provisions relevant to the mortal nature of man.[15]

As Peter Brown aptly summarized, “The most obvious feature of man’s life in this saeculum is that it is doomed to remain incomplete. No human potentiality can ever reach its fulfillment in it.”[16] Avihu Zakai also states, “Divine providence, Augustine believed, is concerned with salvation, not with history as such…the struggle between the heavenly and profane cities, would be resolved only beyond time and history.”[17] R.A. Markus, one of the great historians of Late Antiquity, equally remarked, “The saeculum for Augustine was the sphere of temporal realities in which the two ‘cities’ share an interest.”[18] (That interest being the mutual desire for peace that Augustine writes about in Book 19 of The City of God.)

Augustine’s “pessimistic” view of history, then, is ultimately rooted in his anti-chiliastic philosophy of history. Augustine famously asserted that a republic is an association of rational beings united in love and justice.[19] Despite this, Augustine equally asserted that no true republic can ever be found on earth. The only republic of true justice and love is “found only in that commonwealth whose founder and ruler is Christ.”[20]

There is no separating the wheats and tares in Augustine’s political philosophy, no postmillennial or pre-millennial earthly kingdom that history is working toward. As Augustine himself stated, “[B]ecause God does not rule there the general characteristic of that city is that it is devoid of true justice.”[21] In Augustine’s dialectic, the saeculum of earthly life, politics, economics, and everything in between oscillates between outright libido dominandi and temporary moments of peace until the Final Judgment. Augustine’s realism merely calls humans to action in the defense of whatever temporal and imperfect peace, beauty, and tolerance is found within the earthly city.[22] Since peace is the ultimate aim for all creatures,[23] and since that modicum of peace helps produce a certain level of happiness—this is the best outcome within the civitas terrena that we can hope and work for.

The Edwardsian Revolution

This article is not seeking to address, or highlight, the chasm between Edwards and Augustine to the point of rendering Edwards as a non-Augustinian Christian. Rather, it seeks to highlight and trace the gradual evolution (and secularization) of Edwards’s philosophy of history down to the present and how Edwards departs from Augustine in the field of philosophy or theology of history. In doing so, one should quickly realize how the departure between Edwards and Augustine on their philosophies of history inevitably leads to wide gulf between the formal Augustinians, in the strictest and most committed sense, and the Edwardsians who will slowly embrace greater and greater progressive and social reformist outlooks through the centuries.

It should first be noted that Edwards’s optimistic and progressivist view of history is not unique within the so-called Reformed theological tradition. John Calvin famously prophesied in his reading of Isaiah, “The knowledge of God shall be spread throughout the whole world…He therefore promises that the glory of God shall be known in every part of the world.”[24] There has always been a certain optimistic side to Reformed theology from its very onset, although tied to certain presuppositions of Reformed theology to be sure. Nonetheless, contemporary consciousness concerning the progressive march of history clearly emanates, in some manner, from this theological foundation.[25]

The most important work that details Edwards’s philosophy of history is his own History of the Work of Redemption. In many ways Redemption can be understood as Edwards’s equivalent of the City of God, detailing the work of God in history and the ultimate end to which (sacred) history is moving. The most important aspect of Edwards’s philosophy of history is the intermixing of historia humana with sacred history, something that Augustine rejected in favor of just a strict historia humana over and against the history of the City of God (though intermixed as they may otherwise be). As Edwards begins, “The design of this chapter is to comfort the church under sufferings and the persecutions of her enemies…which shall be manifest in continuing to work salvation for her, protecting her against all assaults…and carrying her safely through all the changes of the world, and finally crowning her with victory.”[26]

In his opening statement, the syllogism of Edwards’s opening reaffirms that the church will be triumphant on earth through history; indeed, history necessarily ends with the church triumphant despite whatever persecutions and sufferings one is suffering in the present. In this manner, human history is sacred history. There’s no other way around the logic of his sentences. And as Michael Hoberman points out, New England Puritans—from the time of the Mathers through Edwards—routinely made connection between New England and New Israel.[27] The result of this was the blurring the lines between “the church” and New England itself. If the visible church existed in New England, then the logic of this necessitates that the success and triumph of New England must be integrally related to the success and triumph of the church in history. To understand the movement of History, one only need look at the “Puritan Experiment” and, in the words of Cotton Mather, “[God’s] New England Israel.”

In Edwards’s philosophy of history there is a greater tendency to read into historical events the unfolding of providential history—as George Marsden aptly summarized, “In Edwards’ scheme of things a remarkable victory over the French was a fitting sequel to the awakenings…Now he had what he considered irrefutable evidence of God’s providential interventions in political affairs.”[28] It is perfectly understandable that Edwards would reach such conclusions stemming from his opening paragraph in History of the Work of Redemption. Furthermore, it fit within Edwards’s larger outlook that “Thus we see how the light of the gospel, which began to dawn immediately after the fall, and gradually grew and increased through all the ages of the Old Testament, as we observed as we went along, is now come to the light of perfect day, and the brightness of the sun shining forth in this unveiled glory.”[29] That Protestant, and more specifically Puritan, New England (and Mother England) were successful in defeating Catholic France, whereby the light of the gospel of Reformed Protestantism could spread, it necessarily followed that Edwards would see triumphant military and political victories over the supposed opponents of the church as evidence of the (providential) progress of history to its glorious end with Christ the King over the Universe.

Edwards’s reading of church history mirrors his reading of human history (which, again, intertwines the sacred and secular together). In detailing the rise of the apostolic church, Edwards highlights the intensity of the early persecutions, Christian overcoming of persecution, the slow triumph of the church fathers—highlighting the roles of Tertullian and Justin Martyr especially—and equating the persecuting Roman Empire with the serpent beast of Revelation, ultimately concluding “[t]hus did the Kingdom of Christ prevail against the kingdom of Satan.”[30] Edwards’s reading of history, here, is remarkable and important for two reasons. First, he again interlinks the triumph of the church with the unfolding events of human history.[31] Second, he associates the temporal world persecuting the church with the “kingdom of Satan.” This does not mean that the world is a temptation and the domain of Satan that needs tamed, but it does implicate that any temporal forces that stand athwart the church is under the power of Satan. Thus, such Satanic kingdoms (in North America’s case, France and Spain) need to be confronted and defeated for the triumph of Christ’s kingdom (which is the church) on earth.

Here, Edwards explicitly references the “church of Rome” as corrupt, superstitious, and wicked, and had previously equated it with the anti-Christian kingdom of Satan,[32] “Satan has opposed the Reformation with cruel persecutions. The persecutions…have been persecuted by the church of Rome…So that Antichrist has proved the greatest enemy of the church of Christ.”[33] Taken as a whole, it becomes evidently clear as to why Edwards interpreted the events against Catholic France as providential favor and intervention in history.

As Edwards outlined from the beginning of the work, the History of the Work of Redemption was meant to bring consolation and confidence to the church triumphant on earth. This completes, full stop, the logical construction of Edwards’s work which began with the persecuted church in antiquity and its triumph as being a sort of foreshadowing for the eventual triumph of the Reformed church in the present day. Edwards achieved, here, a remarkable synthesis of the notion of the church militant (ecclesia militans) with historical situatedness and the march to heavenly paradise.

Furthermore, Edwards explicitly makes reference in the later part of the Redemption of God’s spirit pouring out over New England—again conflating an earthly region with the Christian church and God’s work in salvation.[34] Here Edwards gives a long list of the diminishing nature of the Reformed church in France, Germany, Hungary, and the rest of continental Europe, but its present state of flourishing in New England, “Another thing, which it would be ungrateful in us not to take notice of, is that remarkable pour out of the Spirit of God which has been of late in this part of New England.”[35] Insofar that Edwards was associating the work of redemption and the outpouring of God’s spirit in New England, this ultimately led him to believe that the works of reform, progression, and establishment of the millennium would begin in America rather than anywhere else in the world, “And there are many things that make it probable that this work will begin in America.”[36]

Again, we see in Edwards’s historicist outlook the special role that New England is playing in the unfolding history of the triumphant Christian church. And that history is unfolding in this providential and progressivist manner of triumph over the forces of Satan that undergirds Edwards’s theocentric perspective. New England, indeed, America, has a special place in Providential History from Edwards’s pen and psyche. His intellectual, and cultural, impact upon the rest of American culture and self-understanding in this regard was profoundly consequential.

Moreover, history has now taken on a sacralized element to it. The events of history have meaning and purpose. There is, by Edwards’s own historicism, a “right side to history” and that history’s purpose is culminating in the triumph of the church on earth, which is really the glorification and triumph of God, his beauty, truth, and sublimity in history.[37] And this church has been primarily placed in New England by the providential hand of God for the purpose and end of His work. The most important aspect to Edwards’s re-sacralization of history was his reading of history—that specific events, in the most literal, concrete, and social manner, as literal history pertains to the literal, concrete, and social by definition—which necessarily ensured that historical progress was now directly associated with specific events and outcomes in the world rather than apart from the world. Edwards therefore anticipates Hegel that the providential hand of God is working in the world toward a greater culmination of a sort of an end of history.[38]

As Zakai points out, “Edwards’s evangelical historiography deals with the rise and continued progress of the dispensation of grace toward fallen mankind.”[39] That Edwards sees historical outcomes as the hand of God dispensing grace toward fallen humans, and this represents progress, one also sees in Edwards’s historical outlook the very idea of social progress—even if it is founded on a theocentric foundation.[40] Zakai, again, highlighted the debt of Enlightenment ideas of progress to Edwards’s historicist outlook.[41] Ultimately, Edwards’s historicism of redemptive progress brings an explicit notion of historical and social progress into human history since human history is now intertwined with sacred history. This will have far-reaching ramifications after his death, as his students take up his legacy and push Edwards’s thought to its formal and logical conclusion: social progress is contingently tied to God’s progress of redemption and they become synonymous with each other.

The Edwardsian Legacy: The Universalization and Secularization of Edwardsian Social Theology

Mark Noll has written that Samuel Hopkins, a close friend and student of Edwards, was among one of the first abolitionists calling for outright emancipation from his reading of Scripture in conjuncture with Edwardsian theology.[42] Hopkins himself wrote that slavery was condemned and opposed by “the whole tenor of divine revelation.”[43] (Although it is true that Edwards did not share the same views as Hopkins concerning slavery since Edwards saw it as a Biblically ordained institution.) The first generation of Edwardsian students and inheritors are not only building and modifying Edwards’s theological and historical outlook, they are expanding and universalizing it to its own logical conclusions.

In the case of Hopkins, if history pertains to the triumph of Christ’s church and the social and political victories “[u]ntil the gospel and holy scripture came abroad in the world, all the world lay in ignorance of the true God”[44] as Edwards wrote, then it logically follows if Scripture spoke against slavery (as Hopkins and others believed) and Christ’s church is married to Scriptural social commandments and its flourishing, then slavery needed to be abolished for the full progress of history to be manifested so that the gospel abounds in all places and all persons have a knowledge of the true God.[45] In fact, a major part of Edwards’s philosophy of history is the coming self-glorification of God through knowledge of God and the light of his sublimity being manifested in the world.[46] As Hopkins himself wrote, “the society of the redeemed, the church and kingdom of Christ, will be an eternal imitation and image of the infinitely high and perfect society of the Three-One” (the Trinity).[47] Lemuel Haynes, an African-American Congregationalist minister, himself trained and steeped in Edwardsian theology,[48] equally took up the Edwardsian outlook that the spread of the gospel and the relations of love as fitting the Edwardsian outlook of historical fulfillment.[49]

An integral aspect of the new social theology being promoted by Edwardsian students was the importance the role of social love between humans as a reflection of their love of the true Supreme Being (God), and how the redeemed society of providential fulfillment grew ever more perfected in reflecting love within society as a reflection of the love of God and the Trinity. (This follows the more explicit Augustinian view, for Augustine said “if we see love, we see the Trinity.”) Of course, this entails a moral progression in social life—much akin to how Georg W.F. Hegel outlines the work of the Geist as bringing a greater moral collectivity united in love and compassion as the “True Spirit [of] the ethical order.”[50] In Edwards—and through his students, especially Hopkins—one recognizes a dialectic of loving perfection, “the society of the redeemed, the church and kingdom of Christ, will be an eternal imitation and image of the infinitely high and perfect society of three-in-one.”[51]

The exhaustive historicist consciousness of Hopkins’s statement entails a perfecting society. The redeemed society, in its perfecting image to the redeemed society, exudes greater social love for all members of society. It is an explicitly collective endeavor, since society is, by definition, a collective body. As he even wrote, “the church of the redeemed is the body of Christ.”[52]

While Edwards may not have extended this to the institution of slavery in his lifetime, the logic of his own theology, and historicist outlook, necessarily demanded it. Thus, it is no surprise that his students and pupils took the next step in progressing Edwards’s theology and philosophy of history to its ultimate end. As Robert Nisbet concluded, “Edwards’s roots are indeed Puritan…[b]ut the kind of view of human progress [he promoted is]…the outlook that we find ever more luminously revealed in the pre- and post-Revolution writings of the Founding Fathers.”[53]

Edwards’s philosophy of history is revolutionary because of the necessary conclusions one will have to draw if one really does believe that God’s providential hand in history is leading to the spreading of the gospel and the self-glorification and increased sublimity of love and social ethics between humans as a contingent reflection upon the growing glorification and sublimity of God in history. The inevitable outcome of Edwards’s own philosophy of history is social progress since social progress is equated with the divine work of redemption. As Marsden states, Edwards’s “breathtaking historical perspective…provided incentive for unflagging evangelical action.”[54] Indeed, it is precisely this idea of social progress and “evangelical action” emanating out of the Puritan tradition that sociologist Talcott Parsons described as the origin of “instrumental activism.”[55]

To return, then, to secularism as being the preservation of particular theological outlooks and social habits after the atrophy of theological metaphysics, it is undoubtedly the case that the spirit of social progress in American consciousness is a direct legacy of Edwards’s philosophy of history; thereby imparting into American public consciousness and culture on a broader scale a certain psychological and social action consciousness unrivaled in American history. The idea of a general progress in society, and social relationships, seems irrevocably tied to the ultimate logical end of Edwards’s philosophy of history and necessarily social realism of his theology. The redeemed society, in the new secular picture, is not just the church as the universal society, but the universal society as (an atrophied) reflection of the church. Public consciousness over the need to reform society, create a more perfect union, and establish a society infused and embracing of radical love all have their roots in Edwards’s philosophical theology, philosophy of history, and its inherited and modified legacy as demonstrated hitherto. All of this would reflect the realization of the redeemed society that is both the church and the body of Christ.

Conclusion: The Ironies of American Culture and History

In following the likes of Niebuhr and Hofstadter, one of the great ironies and paradoxes of American culture and history is that the Puritans serve as a greater foundation for many of America’s progressive ideals and beliefs—social progress, education, and self-overcoming—than any other group in American history. The irony, then, is that far from Hegel, Marx, or some foreign infiltration into America, American progressivism and optimism owes more to Edwards and American Puritanism. As George Marsden wrote:

“As with much of Edwards’ work…his views—or variations much like them—eventually became a force in nineteenth-century America. Down to the Civil War, millennial optimism became the dominant American Protestant doctrine. Although Edwards is not usually thought of as a progenitor of the American party of hope, one can easily see continuities between An Humble Attempt and reforming millennial optimism as late as ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’ or even into the progressive era.”[56]

Likewise, George McKenna notes, “The Progressives loved America, but the America they loved was one that began in New England, traversed the North, and defeated the slave-holding South. Its religion was Protestant…It was the muscular, activist, strain of Puritanism.”[57] Just as Talcott Parsons argued that one of the lasting imprints of Puritan culture into American culture was that strain of “instrumental activism,” another one of the lasting imprints into American culture and consciousness is the progressivist view of History bequeathed by Edwards. Long after his death, Edwards’s work, and variations of his work, laid deep roots in the American public psyche and consciousness that would bequeath the full-throated progressive consciousness of national reform and progress. In this sense, Edwards truly is the “American Augustine” and second only to the bishop of Hippo in psychological, historical, and cultural impact in how Christians understand their situatedness in world history. America as central to the unfolding of the history of redemption owes more to Edwards than any of his Puritan predecessors, and more than any of his successors.

Notes

[1] Avihu Zakai, Jonathan Edwards’s Philosophy of History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 1.[2] See R.A. Markus, Saeculum: History and Society in the Theology of St. Augustine (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1970), for a fuller treatise on the subject.

[3] Ibid., 179.

[4] I use the term progressivist, here, in a philosophy of history sense, not necessarily political or social as per the modern revision of the term.

[5] William Barret, Irrational Man, (New York: Anchor Books, 1990 reprint; 1958), 27.

[6] Reinhold Neibuhr, The Ironies of American History (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1998 reprint; 1952).

[7] David Hume, The History of England, From the Invasion of Julius Caesar to The Revolution in 1688, 6 vols. (Indianapolis: Liberty Classics, 1983), 4:14.

[8] Leo Strauss, “The Three Waves of Modernity,” in Political Philosophy: Six Essays, ed. Hilail Gildin (Inidianapolis: Pegasus-Bobbs-Merrill, 1975), 83.

[9] Larry Siedentop, Invention the Individual (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2014), 338.

[10] Robert Nisbet, History of the Idea of Progress (New York: Basic Books, 1980), 196.

[11] Robin Niblett, “Liberalism in Retreat,” Foreign Affairs, 96, no. 1, Janurary/February 2017, 17.

[12] Perry Miller, The New England Mind (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1983 reprint; 1939), 3.

[13] Cf. Nisbet, 66; St. Augustine, City of God, trans. Henry Bettenson (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 19.15-28.

[14] Zakai, 169-171.

[15] St. Augustine, The City of God, 19.17.

[16] Peter Brown, “St. Augustine,” in Trends in Medieval Political Thought, ed. B. Smalley (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1965), 11.

[17] Zakai, 170.

[18] Markus, 135.

[19] St. Augustine, City of God, 4.4, 19.24.

[20] Ibid., 2.21

[21] Ibid., 19.24.

[22] Ibid., 19.17; Markus, xi.

[23] St. Augustine, City of God, 19.12-24.

[24] John Calvin, Commentary on Isaiah, 66.19

[25] See Karl Löwith, Meaning in History: The Theological Implications of the Philosophy of History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949), for a fuller treatise on the relationship between theology of history and philosophy of history.

[26] Jonathan Edwards, History of the Work of Redemption (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board Publication, 3rd edition reprint, 1774), 13.

[27] Michael Hoberman, New Israel/New England (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011), 55.

[28] George Marsden, Jonathan Edwards: A Life (New Haven: Yale, University Press, 2003), 331.

[29] Edwards, History of the Work of Redemption, 232.

[30] Ibid., 248-252.

[31] As already mentioned, this runs counter to St. Augustine’s philosophy of history, where the triumph of the church comes in the Final Judgement where all those who belong to the city of God are judged and brought into heaven while those who belonged to the city of man are damned. The separation of wheats and tares comes only at the Last Judgement, not the unfolding of historia humana.

[32] Edwards, History of the Work of Redemption, 262-265.

[33] Ibid., 277.

[34] Ibid., 286.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Jonathan Edwards, Some Thoughts Concerning the Present Revival of Religion in New England, 33. Accessed http://www.prayermeetings.org/files/Jonathan_Edwards/JE_Some_Thoughts_Concerning_The_Present_Revival.pdf.

[37] Zakai, 210-271.

[38] See R. C. De Prospo, Theism in the Discourse of Jonathan Edwards (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1985), 99.

[39] Zakai, 233.

[40] Refer back to supra notes 10 and 25.

[41] Zakai, 233-234.

[42] Mark Noll, The Civil War as a Theological Crisis (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 40.

[43] Samuel Hopkins, A Dialogue Concerning the Slavery of Africans, ed. Samuel Sewall (New York: Arno Press, 1970), 26.

[44] Jonathan Edwards, History of the Work of Redemption, 257.

[45] Again, Noll highlights how the crisis of slavery was equally a crisis of theology and Scriptural hermeneutics. The crisis itself seems to be clearly rooted in this Edwardsian outlook—the conflict of emerging consciousness between his philosophy of beauty, love, and sublimity with the self-evident antithesis of beauty, love, and sublimity being reflecting in slavery. In this sense, the crisis of slavery and theology was not the genesis of “Liberal Protestantism” and the abandonment of literal readings of Scripture as Molly Oshatz writes in Slavery and Sin: The Fight against Slavery and the Rise of Liberal Protestantism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), but the culmination of Puritan, and especially Edwardsian, theology taken to its exhaustive historicist conclusion.

[46] Zakai, 210-213.

[47] Samuel Hopkins, “The Eternal State of Happiness,” in The Works of Samuel Hopkins (Boston: Doctrinal Tract and Book Society, 1852), 58.

[48] Noll, 65

[49] Ibid., 71; Zakai, 213-220.

[50] Georg W.F. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. A.V. Miller (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), §. 444-487, pp. 266-296.

[51] Hopkins, “The Eternal State of Happiness,” in The Works of Samuel Hopkins, 58.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Nisbet, 196.

[54] Marsden, 334.

[55] Talcott Parsons and Edward Shils, Toward a General Theory of Social Action (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1953), xviii.

[56] Marsden, 337.

[57] George McKenna, The Puritan Origins of American Patriotism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 191.