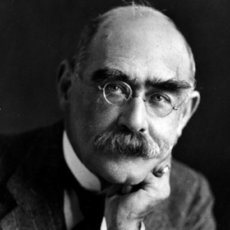

Rudyard Kipling or G.K. Chesterton: But Not Both

When G.K. Chesterton died on Jun 14, 1936, about six months after Rudyard Kipling, both men were long out of fashion, By now, as they recede in our vision, surely we ought to have some sort of consensus on both men.

Not hardly.

Each author still has devoted fans and each makes some people angry.

Why, after so long?

To be sure, Kipling was a grating individual, full of unedifying bigotries, but there were lots of people at the time just as irritating (Gandhi for one). And one could say that as a versifier of a genuinely populist kind, without being much of a democrat, he represents a literary road not taken, a road that must not be taken. And of course there are live political issues — he supported the British empire, and that louche phenomenon has not yet received the verdict of history.

But these causes are, I believe, epiphenomena. It is not Kipling’s particulars that repel, for those who do not like him, but what we may call his moral flavor.

Kipling is sometimes called conservative, but it is the conservatism of despair. He had seen a lot of the way the world was run, and he had a low opinion of the ability of the human race to run it. If he supported empire, it was because he had seen anarchy. No, the universe is hostile and man is weak. In Kipling’s vision we walk on a thin floor of order (not a very pretty floor, either). But to fall through — it’s a long way down and it’s all dark.

It is not a Christian view and certainly it is not a progressive view.

For what if he was right? Or even partially right? How shall we improve man when we have to struggle just to keep the streets clean? If there is truth in Kipling, there is little comfort.

Chesterton, on the other hand, has his own mystery.

There are things that ought to put Chesterton in current favor. He was an anti-imperialist and a foe of big corporations and globalism:

Our principle exports, all labeled and packed,

At the ends of the earth are delivered intact . . .

So that Lancashire merchants whenever they like

Can water the beer of a man in Klondike

Or poison the meat of a man in Bombay;

And that is the meaning of Empire Day

And he had a strong love for the local — this or that street or suburb. And he felt that it was vitally important that the ordinary Joe or Jane has an actual property stake in society and the practical freedom to make personal economic decisions. Yet it is in this very localism, attractive as it is, that we find a key to what drives certain people to distracted fury.

Chesterton, we may argue, was the last great Aristotelian populist. If he had had a motto, it might have been (as he said about Aquinas): “eggs is eggs.” What is real is what is there in front of you. This street, that suburb. This person or that. Now.

That sounds very nice, but if what is real is what exists, what is the reality status of our social theories? Our plans for the future, the omelets for which we are cracking all those eggs?

Bad enough, but worse follows. Chesterton is an Aristotelian without being a materialist. The eggs, the bus, the man on the bench, each is real all right, but its significance extends beyond itself. For Chesterton, the world was more than the world, it was a conspiracy.

The world had been made real for a reason, and Chesterton thought he had a good clue as to the motive. Moreover, the someone who had made the world had acted within its bounds. In fact, a plot had been launched, and it was in progress.

It wasn’t theory. It was as much a fact as Pittsburgh.

Now if the world is like a stained glass window through which shines a steady radiance, a real window, a real radiance. But that radiance was a single radiance, from one source and with one angle.

Whence relativism? Whence tolerance? Opinions like this are too dangerous to even refute. What would happen if the servants overheard?

To conclude, as with Kipling, we are dealing not with this or that detail but with a moral atmosphere.

Some people find that atmosphere mountain air. Others find it mustard gas. No resolution is possible in such cases. As my grandmother used to say, injustices may be corrected, and hatreds reconciled, but distaste is forever.