Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets

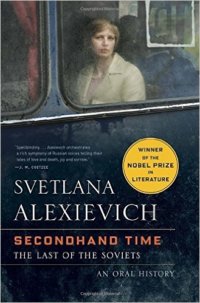

Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets. Svetlana Alexievich, tr. Bela Shayevich. New York: Random House, 2016.

One of Dostoevsky’s more profound and even prophetic philosophical questions is posed by Ivan, the intellectual, to his younger brother Alyosha, the aspiring monk, in The Brothers Karamazov: Would he find the torture of one child acceptable if it was somehow the necessary means of creating heaven for everyone else? Ivan uses this question to vindicate his rebellion against a God he claims is morally evil for willing an ultimate perfection in the remote future while permitting the suffering of innocent children in the present. Alyosha, who, unlike Ivan, is a believing Christian actively engaged in loving children, says he would not find such torture acceptable, which is the answer that Ivan expects and wants. But in Ivan’s rebellious question Dostoevsky foreshadows the ideology-justified tyrants of the twentieth century who would not base their rejection of God on the suffering of children but instead would be entirely willing to impose a much higher price in human suffering for an earthly paradise than that suggested by Ivan, not only by oppressing, torturing and murdering millions but, more metaphysically, by attempting to annihilate the human person.

In his recent book Politics of the Person as the Politics of Being David Walsh points out the essentially transcendent nature of persons and presents in more concise form the answer to Ivan made by the Elder Zosima in Dostoevsky’s novel: “Whatever benefits might accrue to the whole society, they are not worth gaining if it means the sacrifice of its humblest members. In this sense each is a whole outweighing the whole…. We simply know that we do not wish to belong to any society that would live at the expense of its most vulnerable members.” Unfortunately, this is not intuitively true to those whose ambition is to employ absolute political power to contort reality into the contours of an Idea. Since to treat human beings as persons would mean abandoning their ambitions, they instead reduce human persons to statistics and the raw material of a pretended process of social development. Nadezhda Mandelstam, in her memoir Hope Against Hope, explained the human cost eloquently in terms of human persons: “For the sake of what idea was it necessary to send those countless trainloads of prisoners, including the man who was so dear to me, to forced labor in eastern Siberia? M.[the poet Osip Mandelstam] always said that they always knew what they were doing: the aim was to destroy not only people, but the intellect itself.”[1] Secondhand Time, by the Nobel prize winning author Svetlana Alexievich (and very well translated by Bela Shayevich) is an account of the ways other than murder in which the Communist ideological lie destroyed persons and intellects.

In his discussion of Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts in Science, Politics and Gnosticism Eric Voegelin makes the case that, as a gnostic thinker who chose to persist in a revolt that he knew was against God and therefore based on untruth, Karl Marx was an intellectual swindler. Unlike the usual run of swindlers who cheat people for monetary gain, intellectual swindlers create a false reality so that they might be its god. In other words, “the revolt against God is revealed and recognized to be the motive of the swindle.”[2] Since the gnostic thinker is fully aware of what he is doing Voegelin calls this deception “demonic mendacity.”

Lies, of course, beget more lies. The unlimited political power necessary for replacing reality with the imaginary “perfect” worlds such gnostic intellectuals create provides a pretext for despotic souls to destroy human persons as incompatible with the impersonal future “paradise.” The “murder of God” entails attempting to force reality into a structure devoid of transcendence and the inescapable tension toward it in human consciousness so that man might become his own supreme being. For the lie that reality is malleable and subject to the demonic wills of the intellectual and the despot, other people inevitably pay the terrible price. As Voegelin put it, “Man cannot transform himself into a superman; the attempt to create a superman is an attempt to murder man. Historically, the murder of God is not followed by the superman, but by the murder of man: the deicide of the gnostic theoretician is followed by the homicide of the revolutionary practitioner.”[3] And such homicide is not only by the destruction of physical life. It is also a relentless campaign to replace persons, beings with spiritual lives, with the “new men” devoid of spirit required by the new reality.

Because the Soviet Union was a country—an empire, really—founded entirely on this swindle as an attempt to subjugate reality to the will of Karl Marx and his power-hungry acolytes, the Communist world has served as a “clinical trial” in which we can study the destructive consequences of the intellectual’s libido dominandi. There are, of course, numerous books written by Soviet “dissidents,” survivors of the Gulag, and scholars of Soviet history, but Secondhand Time serves as a particularly poignant “tour” of the human wreckage of gnostic homicide because it consists entirely of transcripts of interviews with ordinary people, some of whom have difficulty fathoming what happened to them while others are painfully aware that they were cheated. Over a period of twenty years after the collapse of Communism Alexievich traveled around the former Soviet Union with her tape recorder, allowing intelligent, articulate persons who were neither famous nor dissidents nor authors of books to talk about their personal lives in a society relentlessly pursuing the unreal. She also includes random comments and snatches of overheard conversations. Consequently, after the Introduction there is little in this book in Alexievich’s own voice. Instead there are many other voices that describe the long-term consequences of the murder of man.[4]

This is a long book that is often difficult to read because of the massive evidence of the swindle’s human destruction in anger, despair, suicides, betrayals, broken families, ethnic hatreds, murders, and children relegated to abysmal orphanages after their parents were arrested, parents who either never returned or returned many years later as strangers, shadows of their former selves. There are people whose entire lives were lived in deprivation and squalor, “sacrifices” that they were told were necessary to build the just and equal society of Communism (or Socialism). There is, not surprisingly, a great deal of bitterness and disillusionment, for some because they recognized that Communism was a lie that ruined their lives, but for others because they cannot permit themselves to stop believing the lie and are convinced that Communism fell by a terrible betrayal. Many are angry because it seemed that overnight the socialism they thought they were building was abruptly replaced by its supposedly quintessentially evil archenemy, capitalism, and by what they were told were freedom and prosperity but which turned out to be, for them, rule by kleptocrats and impoverishment caused by devaluation of the ruble. And some people recount the horrors inflicted on them in the 1990s when they were caught up in the sudden eruption of ancient ethnic hatreds that long had been suppressed by the Communist dictatorship.

At the beginning of the book Alexievich explains what she is doing in her interviews as “piecing together the history of ‘domestic, ‘interior’ socialism, as it existed in a person’s soul.” (The whole notion of a person’s soul was one incompatible with Communism.) She begins her introduction, which is titled “Remarks from an Accomplice,” with the statement that “We’re paying our respects to the Soviet era. Cutting ties with our old life. I’m trying to honestly hear out all the participants of the socialist drama . . .” This is indeed an attempt to shed light on the psychological effects of an ontological swindle, what she calls “Communism’s insane plan: to remake the ‘old breed of man,’” a plan that, she says, really worked in that it produced a “new man”: Homo sovieticus. Such human specimens exist in every nationality of the former Soviet Union and they are “like and unlike the rest of humanity—we have our own lexicon, our own conceptions of good and evil, our heroes, our martyrs. We have a special relationship with death….How much can we value human life when we know that not long ago people had died by the millions?” Some, she says, regard the new Soviet man as a tragic figure but others call him a sovok, which, as Alexievich explains in an endnote, is a common pejorative term for someone who adheres to Soviet values, attitudes, and behaviors. It is also a satiric pun on the actual Russian word sovok that means “dustpan.”

I think that this book is most accurately understood, perhaps, as an investigation of the pneumopathological effects of the swindle, which were primarily an enslavement that the slaves, those who had been deeply penetrated by the Soviet idea, often failed to recognize. Herself a member of the “Gorbachev generation,” Alexievich notes that “no one had taught us how to be free. We had only ever been taught how to die for freedom,” that is, they were enslaved to the imaginary Marxist idea of future freedom. She found some people who even liked being slaves, who found freedom irritating and were annoyed when confronted with competing views and differing accounts of the truth because their former conditioned belief that Pravda (Truth) contained all that they needed to know prevented them from ever developing any critical faculties. One of her interviewees comments that “Our people need freedom like a monkey needs glasses. No one would know what to do with it.” She reports that when the archives were opened after the fall of Communism “people sat in stunned silence overcome with horror. How were they supposed to live with this?” One way was to treat the truth as an enemy and another was to adopt the status of victim, which was easier to accept than that of willing accomplice in evil.

Disappointment pervades the interviews. At the beginning of the book there are people who remember the August 1991 “putsch” attempt as a time of wild optimism that their lives would suddenly be filled with the freedom and prosperity they had always been promised. There are others, nostalgic for the ideals of the past, who are bitter that the noble, unselfish ideal of Communism was replaced by greed for wealth. They feel as though they are living in a foreign country where life has less meaning. Some claim that they never had real Communism, just Stalinism. And there are those who have started going to church, some of whom do not believe in God, as though having been betrayed by one god they are afraid to believe in another. One particularly bitter woman, who knows that she was deceived, laments that she waited and waited for the good life to come but now she is too old. “We spent our whole lives believing that one day, we would all live well. It was a lie! A great big lie! And our lives…better not to remember what they were like…We endured, worked and suffered. Now we’re not even living anymore, we’re just waiting out our final days.” After a lifetime of indoctrination that their sufferings were necessary to build the radiant future of socialism they were told one day that unfortunately it had all been a mistake and socialism was over.

As a documentation of the spiritual, psychological, and even physical suffering of those who served as the cannon fodder for the Marxist war against reality Alexievich’s book is not unique. There are, by now, countless books that bear witness to the sheer evil of Communism in every aspect of the regime, Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago being one of the preeminent examples. But this book is an important addition to the Sovietica library because of the number of witnesses to the power of demonic mendacity to undermine human persons. One of the most haunting stories in this book is that of a woman who lived with her five-year-old daughter and twenty-five other people in a communal apartment in the 1930s. One of the other residents was a childless woman who was the friend of the mother. Someone denounced the mother who was arrested and carried off with only enough time to entrust her daughter to her friend, whom the daughter came to call Mama Anya and who was given a second room. Seventeen years later, around 1954, the mother returned from the camps and kissed the hands and feet of her friend in gratitude for raising her daughter. When the archives were opened after Gorbachev came to power in 1985 she was asked if she wanted to see her file. She did, and that is how she learned that the person who had informed on her in 1937 was Mama Anya. She went home and hanged herself. This is the effect of demonic mendacity on the scale of one soul who had for decades clung to the belief that there was at least one good, honest, selfless person in the world. The woman who related this story then quoted her father’s sardonic comment that “It’s possible to survive the camps, but you can’t survive other people.” In a regime based entirely on demonic mendacity and the ruthless enslavement and murder of human beings, few persons are untouched by the pathology of the spirit.

Finally, the title of the book is ultimately based on a remark written by the novelist and short story writer Alexander Grin shortly before the 1917 Revolution: “And the future seems to have stopped standing in its proper place.” To which Alexievich adds “Now, a hundred years later, the future is, once again, not where it ought to be. Our time comes to us secondhand.” I think what this means is in what she reports before it. In the nineties many people were ecstatic because they believed that it would be impossible to return to the miseries of Communism, “that the choice had been made and that communism had been defeated forever. But it was only the beginning…” Young people born after the collapse of Communism have known only the Russian kleptocratic version of capitalism, so “they dream of their own revolution.” All things Soviet are in demand, and there is even a nostalgic admiration for Stalin, the strong man who really knew how to run the country. The party that currently rules Russia does not call itself Communist but it follows the methods of the Communist Party, the Russian president has absolute power like the former General Secretary of the Communist Party, and “instead of Marxism-Leninism there’s Russian Orthodoxy” as a kind of national religion. In short, demonic mendacity seems to be making a second appearance, perhaps this time as farce.

Read Alexievich’s book as a testimony to the seductions and ravages of ideology.

Notes

[1] Nadezhda Mandelstam, Hope Against Hope: A Memoir, tr. By Max Hayward (New York: Atheneum, 1980), p. 363. Nadezhda Mandelstam was the widow of Osip Mandelstam, considered by many to be the greatest twentieth-century Russian poet. Because he wrote an unflattering poem about Stalin he was arrested in 1937 and sent to eastern Siberia where he presumably died within a few months. This is Nadezhda Mandelstam’s first volume of memoirs, the second being Hope Abandoned. The titles are puns on her name, which means “hope” in Russian.

[2] Eric Voegelin, Science, Politics and Gnosticism, 34.

[3] Ibid., 64.

[4] Alexievich does provide her own commentary in the chapter titles, such as “On a Time When Anyone Who Kills Believes That They Are Serving God,” “On the Beauty of Dictatorship and the Mystery of Butterflies Crushed Against the Pavement,” “On Wanting to Kill Them All and the Horror of Realizing That You Really Wanted to Do It,” and “On the Darkness of the Evil One and ‘the Other Life We Can Build Out of This One.’”