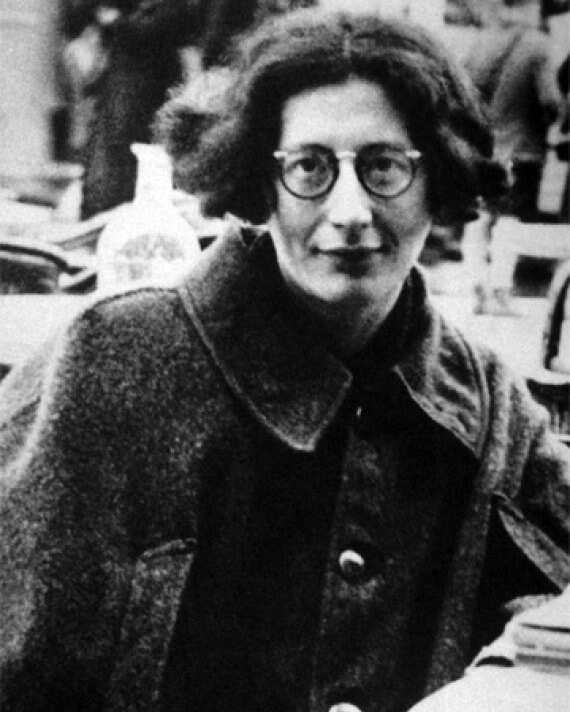

Simone Weil’s Metaxu (Basho, Heaney)

The Poem as Metaxu

As one learns more and more about poetry, one begins to appreciate how a poem relates to a universe of poetry; we haltingly speak of “echos” of Shakespeare and Virgil in the simplest rhyme. In her remarks on “Metaxu” collected in Gravity and Grace (University of Nebraska Press, 1992, 200), Simone Weil writes, “The essence of created things is to be intermediaries. They are intermediaries leading from one to the other, and there is no end to this. “

By “there is no end to this” I understand not only that a given poem may have unacountable connections with other poems, though that’s true; but also, there is no end in sight to the process begun with our attention to the created thing: “They are intermediaries leading to God.” “Metaxu” lead us to God.

And she adds, “We have to experience them as such.”

To know poems as metaxu, we need to “experience” them as such. We need to pay attention to the double nature of every poem, as structure and as trace of the Good. Here are two examples. (In the following, we will use the derivative terms “metaxy” and “In-Between” and “between” as needed to make our meaning clear.

First, a haiku by Basho (1644-94):

though the autumn wind

has begun to blow, it is green –

a chestnut burr

(trans. Makado Ueda, Basho and His Interpreters, Stanford, 19992, 319))

The paradox of the “green” chestnut bur captures Basho’s imagination. We feel the first cold winds of autumn, yet note with wonder that the chestnut bur is still green. The chestnut bur awakens in us a resistance to the necessity of nature’s law, as if the chestnut bur by being green were doing something impossible. Yet we identify with that tough, ugly little seed pod, and its singular greenness, and know it will do its part in bridging between now and spring time. Basho’s ironic self-portrait has a spiritual seed within the prickly exterior of the two-part haiku.

Longer poetic forms allow greater differentiation of the between. Whereas the form of the haiku elegantly enfolds the meditative process leading to the metaxic vision, longer poems can follow the contemplative steps by which the metaxic vision is reached, thus fulfilling the promise of poetry as metaxu. The work of Irish poet Seamus Heaney (1939–2014) overflows with luminous images of the metaxy, often, as in Basho’s haiku, things otherwise unpoetic.

The Perch

Perch on their water perch hung in the clear Bann River

Near the clay bank in alder dapple and waver,

Perch they called ‘grunts’, little flood-slubs, runty and ready,

I saw and I see in the river’s glorified body

That is passable through, but they’re bluntly holding the

pass,

Under the water-roof, over the bottom, adoze

On the current, against it, all muscle and slur

In the finland of perch, the fenland of alder, on air

That is water, on carpets of Bann stream, on hold

In the everything flows and steady go of the world.

From the opening play on words – “Perch on their water perch” – introduces the equivocal nature of things in the between. And Heaney “sees” these small “little flood-slubs” as they hold steady against the flow of the river, flow and counter-flow. In creating this image of the river, Heaney draws on the sacred vocabulary of his Catholic upbringing: “the river’s glorified body.”

In less firm hands this allusion would feel applied or decorative. But as in Voegelin’s image of the metaxy,

“the experience is luminous to itself as a divine-human movement and countermovement, as a movement of revelatory appeal from the divine side and a countermovement of apperceptive and imaginative response from the human side. . . .”

The poem begins with the perch, pure and simple; then it yields to the poet’s curiosity, his attention to something that resonates: “bluntly holding the pass, / under the water-roof, over the bottom, adoze / on the current.” These perch prompt a memory. The kenning “water-roof” echoes pre-Christian British poetry. The martial imagery of “holding the pass” calls forth the history of the river Bann as a place sanctified by Irish resistance.

“The divine side . . . the human side.”

By this time the reader experiences reading as a partnership with the poet and the communion of readers. We are all in this together, a contemplative community. Having moved from the hic et nunc of the object, and through the historical and into the personal, we finally come to a transcendent sense, a deeper sense of being. The final image – “on hold / In the everything flows and steady go of the world” – captures the paradox of the metaxy in light of the ultimate.

In my experience of poetry, good poems reveal the structure of the metaxy, the directional tensions within it, and the enveloping wonder of being. Good poems are metaxu.