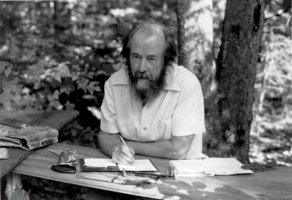

Solzhenitsyn at One Hundred

“Live not by lies,” was the advice that Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (born December 11, 1918) gave his compatriots when they asked him how to stand up to the crushing might of the Soviet Union. He did not seek an open confrontation with the regime. Neither resistance nor violence could succeed in the face of a remorseless killing machine. Individuals would simply be ground without a trace. This was the aim of the vast apparatus of prison camps into which he had fallen, along with millions of his contemporaries, as he discovered in 1945. Opposition was futile, only collaboration with his captors promised any chance of survival. Destruction of life on a mass scale was the intended purpose of the vast dragnet that ingested ever widening circles of suspect categories of human beings. Yet limitless cruelty could not succeed in its most important goal. It could not kill the human spirit. That is Solzhenitsyn’s legacy to world history.

It surely ranks with the greatest medical or technological breakthroughs of our era. None of the latter succeeded in conquering the mortality that is the fate of every living being. Yet Solzhenitsyn did accomplish just such a remarkable feat. He uncovered what is indestructible in a person. Religion and philosophy had always talked about the immortality of the soul, but few had so clearly lived it or, if they did, articulated it so deeply. For Solzhenitsyn, immortality was not a vague notion of another life but that part of himself that could not be destroyed. That is why he hailed the zeks, the prisoners, as a new breed of humans. Having found what endures beyond the grave they had become deathless. What is stronger than death can neither die nor be killed. The unconquerable cannot be conquered, as Nelson Mandela too discovered on his parallel path. It is a shocking realization for the most ruthlessly brutal regimes in history. They come up against what Vaclav Havel called “the power of the powerless.”

Communist authorities had told themselves the lie that they possessed the power to remake humanity. But they could not work their will on those who would not be subdued. This is the turning point that Solzhenitsyn discovered and depicted in his monumental Gulag Archipelago (1974). The freedom he found within himself was at the same time the first crack in the ideological edifice. Total power required the lie that rationalized its unlimited violence. Once the lie is resisted its power too begins to dissolve. By saying no to the lie he had also checked its destructive force. A small hint of the formidable power of this witness was on display in the overnight fame he gained when the government, in the person of Nikita Khrushchev, permitted publication of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962). This was the story of one day in the life of an average prisoner in one of the Siberian camps, but one who through it all had managed to preserve his human dignity. It was an opening that exposed the fragility of the regime. Who could control such a spirit?

Solzhenitsyn would not get another such opportunity as the authorities realized too late what they had unleashed. It was not only that defiance had now become possible but that their need to deny such freedom had been shown to be indispensable. Twelve years later Solzhenitsyn would become such a public relations headache that the Brezhnev government would decide to bundle him onto a plane to Zurich without possibility of return. It was only after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the publication of his works in Russia that Solzhenitsyn was able to return in 1998. What had seemed like an external event in the history of world, the disintegration of Communist power, had had its inner beginning in the realization of its insubstantiality by Solzhenitsyn and the tribe of dissidents. They had been the first to confront the lie and in doing so had made it clear that the whole construction was based on nothing. A lie has no reality. By pronouncing its doom, he had become the most formidable opponent of the totalitarian might that would now crumble from within.

Resistance to violence, whether perpetrated by states or individuals, begins with the refusal to lie. Even in our era when the possibility of truth is casually dismissed as “post-truth” or “fake news,” the force of Solzhenitsyn’s admonition remains. He knew that the question of the line between truth and falsehood was open to dispute. But he did not allow that to provide an excuse for not taking a stand. Begin with the truth that you know, he counseled his contemporaries, and then you will find that the circle of truth begins to expand. It is those who are united within that arc of truth that constitute the community of free persons. Certainly the millions of victims who perished in the totalitarian camps, and continue to do so today, have not managed to defeat the lie that absolved the perpetrators from accountability. History does not always align with justice, but it cannot stop its ears from the judgment of those who have gone beyond mere survival within it. It is in their perspective that we experience the full weight of the proverb that became the centerpiece of Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel Prize Address. “One word of truth outweighs the whole world.”