The Caine Mutiny Court Martial

Or, Is it Worthwhile to Psychoanalyze Politicians?

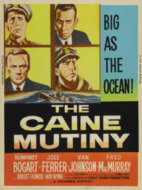

There was a time, not too long ago, when amateur psychoanalysis was in the toolbox of students, intellectuals, and even the smart set. It was marvelous! If you knew just a few facts about a person you could plug the facts into the Freudian system and imaginatively destroy him. And without Freud’s ghost hovering, it is unlikely either Herman Wouk’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Caine Mutiny (1951), or the later movie of the same name (1954) would have taken the form they did.

Today the grandchildren of that generation are not much interested in psychoanalysis. Voegelinian analysis of pneumopathology certainly provides a superior tool for Voegelin readers. For a wider public a strong argument can be made that a psychology based on doing good and avoiding evil is more useful to the individual than trying to recover forgotten childhood experiences in order to explain unhappiness. The facultative psychology of the Scholastics, most notably in the work of St. Thomas, may be the best path to emotional well-being.

In any event, we no longer have a shared psychological vocabulary at hand as we had with psychoanalysis, Freudian or otherwise. Voegelin did point out that Freudian psychoanalysis was a reaction against Positivism, and that insofar as Freud looked beneath the surface, he was going in the right direction. He had rediscovered the soul. Then Freud was disestablished by a number of successful criticisms, including Philip Rieff’s Freud, the Mind of a Moralist, which Voegelin particularly admired. Among other things, Rieff analyzed Freud’s Moses and Monotheism and showed how inconvenient passages in the Old Testament had been ignored to make the argument appear persuasive.

Psychoanalysis had also been used to threaten and coerce people. One could hardly find a better account of this in turn-of-the-century Vienna than Thomas Szasz’ Karl Kraus and the Soul Doctors. Most importantly, people eventually noticed that, as a science, Freudian psychoanalysis offered little predictive value and limited healing power. And then along came drugs to help people with emotional problems and depth psychoanalysis receded even further into the cultural background. But psychoanalysis did offer great entertainment value, whether at a cocktail party or on the stage or in film.

Now to the movie. In the 1954 Hollywood production of The Caine Mutiny, Lieutenant Commander Philip Francis Queeg, Captain of a destroyer-minesweeper engaged in combat in the Pacific theatre during World War II, is relieved by his subordinate officers because they believe he is incapable of exercising rational command during the crisis of a typhoon at sea. Back in the United States, these subordinates are tried before a general court martial on a charge of mutiny, which upon conviction, carries a penalty of death. A psychiatrist appears as a prosecution witness and testifies that in his opinion Captain Queeg is sane. The psychiatrist is then cross-examined, resulting in one of the better court room sequences found in film. (In the film’s denouement, it is argued that had the crew shown loyalty to Captain Queeg instead of attempting to psychoanalyze him, there would have been no crisis at sea and no court martial.)

Whether the personality-type suggested by a Captain Queeg resembles one or more current or past politicians and whether psychoanalytic categories remain useful is left for the reader to consider—all in a tongue-in-cheek spirit, of course!

Defense Attorney: You said Lt. Commander Queeg, like all adults, had problems, which he handled well. Could you describe the problems?

Psychiatrist: The overall problem is one of inferiority feelings arising from an unfavorable childhood and aggravated by some adult experiences.

Def Att: What were those adult experiences?

Psych: He had undergone a lot of strain in long, arduous combat duty.

Def. Att: Would he be inclined to admit mistakes?

Psych: Well, none of us are. (Laughter)

Def. Att: Would he be a perfectionist?

Psych: Yes.

Def. Att: Inclined to hound subordinates about small details?

Psych: Yes.

Def. Att: Would he be inclined to think people were hostile to him?

Psych: Yes, that’s part of the picture.

Def. Att: And if criticised that he was being unjustly persecuted?

Psych: Yes, as I say, its all one pattern stemming from one premise: that he must try to be perfect.

Def. Att: Now Doctor, you have testified that the following symptoms exist in Lt. Commander Queeg’s behavior: rigidity of personality, feelings of persecution, unreasonable suspicion, a mania for perfection, and a neurotic certainty that he is always in the right. Doctor, isn’t there one psychiatric term for this illness?

Psych: I never said there was any illness.

Def. Att: What would you call a personality that had all these symptoms?

Psych: A paranoid personality, but that is not a disabling illness.

Def. Att: What kind of personality, Doctor?

Psych: Paranoid.