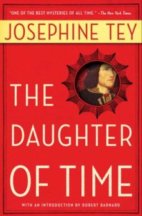

And Prayers Come Limping After: The Daughter of Time

On our desk lies an elderly paperback, somewhat yellowed and a genuine curiosity.

In the upper right hand corner is a green seal with a penguin.

In the center of the cover is a face: a man, beardless, of middle age, wearing a fur cap with an elaborate jewel. His face is calm, but somber. The eyes look withdrawn, the lips are thin and tight. The subject looks like a worried man in a tough business.

The book is The Daughter of Time, from 1951, by British (Scottish to be exact) crime writer Josephine Tey (real name Elizabeth Mackintosh). It is a detective story, of sorts.

First the facts: There is not a lot of action in this story (nothing here for Jerry Bruckheimer). CID man Alan Grant (did I mention the author was Scottish?) is in hospital. He is given a sheaf of portraits from the National Portrait Gallery with which to amuse himself — Grant is supposed to be good at reading faces.

One of the portraits is of the man mentioned above. Grant finds the face sympathetic, and is surprised to learn it is Richard III, old Tricky Dick Plantagenet himself.

Stung by this gap between his impression and the subject’s reputation, Grant investigates, helped by an actress friend and a young American scholar (Tey does Americans better than Agatha Christie, but it is a low bar). The whole operation is carried out from the hospital room, a unity Aristotle would applaud.

It is no spoiler is to say that Grant concludes that Richard Plantagenet did not deserve the reputation Shakespeare gave him, was not guilty of murdering his nephews, and has been the victim of gross political spin.

A lot of people feel strongly about this book; it is one of a small number of books (another is The Art of Thinking) that go steadily on, flying below the radar as it were, changing people, one person at a time. Your columnist read it when he was fifteen and has never forgotten it.

It seems worthwhile to ask why.

First, the story is surprisingly lively for something that centers on a hospital bed and a lot of archaic documents. The dialogue is quick and pointed and the characters appealing. Tey, under the name Gordon Daviot, had been a successful dramatist, and it shows.

Actually, although The Daughter of Time is formally a novel, species: mystery, it is in fact a re-born version of a very old thing: a dialogue. Under the machinery of the story the author is presenting an argument, led through twists and turns to a judgment. At the centre, immobile on his bed, is a man of inquiries, around him rotate the entertaining partners of his dialectic.

Really, it is like meeting a twentieth century Epînician.

The subject matter of the dialogue is affective on a couple of levels.

First of course we can play the counterfactual game.

Richard III dead leads us to wonder what Richard III triumphant would have come to. Would the Plantagenets have marched on through the renaissance without the religious revolution of the Tudors?

Of course we have no idea. We have no idea either as to what would have happened if the secret service had been on the ball at Ford Theatre, and speculation on the latter case is as entertaining and as useless as on the former. Nevertheless, the contingency of history strikes the heart sharply. History is a tissue of regrets.

But beyond this what-if-ness, The Daughter of Time usefully reminds us of the contingency of historical record.

The best historical record can be but a sketch of what actually happened. But beside that built-in uncertainty we need to allow for a massive dose of old fashioned prevarication. The characters discuss this point, with American and British examples.

Now this is hardly a new thought. But it is wholesome to remember the point and if you meditate on it for a little, you begin to hear the thin ice creaking under your feet.

We remember the famous and obscene fresco at Pompeii that has delighted generations (it is the couple on the tight-rope, if you want to know) and is in fact (as Classicist Mary Beard has pointed out) 95%reconstruction. From what was actually left on the wall we can pick out part of an elbow, part of a shin, and a long brown line below, which could be a floor for all anybody knows.

What other lies have we been fed? On what misapprehensions are we building our day-to-day here and now partialities and efficient hates?

These points touch our intellect.

But at the core of this novel, is a deeper issue: a matter of justice. A public man has been traduced (argues Tey) and the injustice has been cemented into the wall of popular culture. This novel, this dialogue, is an effort to make amends for something that is not fair.

No wonder the novel is a minor classic. We have all suffered wrongs, and most of us have done some, too. When someone does something about it, even on a case as cold as this, it cannot fail to appeal to generous hearts.