Yin-Yang, Buddha and Plato’s Cave at the Dawn of the Covid Age

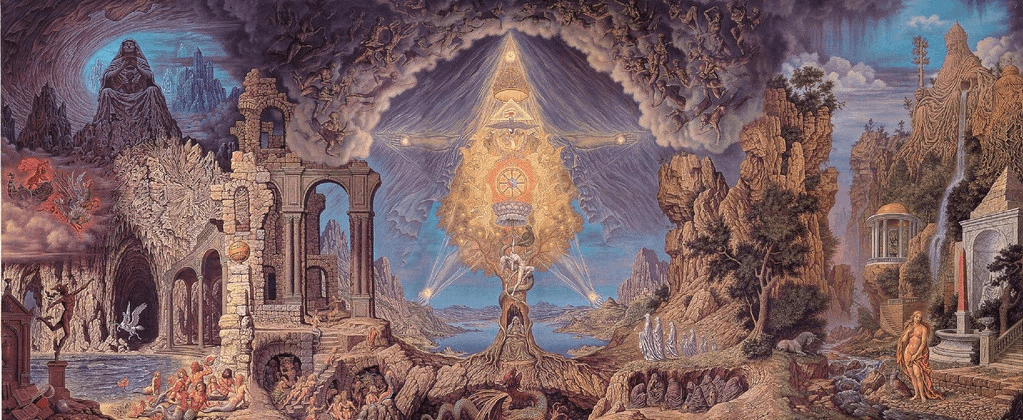

At the dawn of the “Covid Age” the prospect of a quantum-like leap into an unprecedented consolidation of what is known as the Global Society is overtaking billions of lives. What is the Global Society? It is modern man’s dream, a dream that was first sketched hundreds of years ago by thinkers of the caliber of Machiavelli, Hobbes and Spinoza, political strategists who lay out the blueprints for a new world based on quantifiable data devoid of any meaning other than the one produced in the context of the construction of the new world. The writings of early-modern political philosophers ushered into a world in which nature—everyday life and death—was to be conquered, or, to echo Giacomo Leopardi, transplanted onto strictly technical grounds. Now, this could be possible only via a radical abstraction or separation that is perhaps best understood, today, with respect to the ancestral image of Yin-Yang, composed of interlocked dark and light elements.

The modern world is supposed to be made of only the bright side, the Yang, or, to speak with Descartes, only what is “clear and distinct”. Yet, in abstracting the Yang or male from the Yin or female, modernity modifies the Yang, stiffens it, blinds it to its dark counterpart. The Yang loses its direction, its telos, and thus its fluidity. No longer can we speak of life’s natural course, or of the marriage of life and death, or, again, of the coincidence of living and dying. Death as such is shunned, while admitted only as fuel to foster the cause of a new Yang—a new reason that lords it over all otherness, all that does not bow to its dictate.

The new Yang is the element of a new world “globalizing” all diversity into a homogeneous universality: the heralding of diversity via the demonizing of old unities (including old political identities and communities) serves as Trojan Horse to the dispelling of all diversity, or the complete neutralizing of diversity, the emptying out of diversity of all meaning. This is achieved where alterity or otherness is denied, eradicated in the name of progressive universality. The extradition of the Yin allows the Yang to divide all for the sake of reducing all to its empire. Once Yin or death is exiled from the new Yang consciousness, all that counts as “world” for us falls straight under the dominion of the logic of production, as if destruction were not inherent in all production, as if death were not integral to life.

Such is the Yang world that has been consolidated in recent months, in the name of a “crown” virus. The covid-19 marks the beginning of a new era of alleged transparency, where all seems to be self-evident to the extent that all alterity—including the very suspicion of a point of reference other than the official one of the new Yang—has been banned, if only through ostracism. The official, bright side of life that is supposed to be the incarnation of transparency itself, is the greatest of all masks, the greatest sign of imposture, exemplified so glaringly by the official world-discourse about covid-19; a discourse demonizing all alternatives to it, as “fake”.

The triumph of our official global-discourse cannot help remaining superficial, and thus thin-skinned. The triumph of appearance cannot overcome the threat posed to it by the insurgence of alternatives out of the darkness of a Yin repudiated as alien to Yang.

To better understand the new Yang’s position vis-à-vis Yin, it would help dub the two elements respectively as Convention and Nature—nomos and physis. There where Convention triumphs, succeeding in pretending to have vanquished all opposition, Nature, dark cradle of opposition by antonomasia, becomes its enemy. Nature stands as the negation of all that Convention claims for itself.

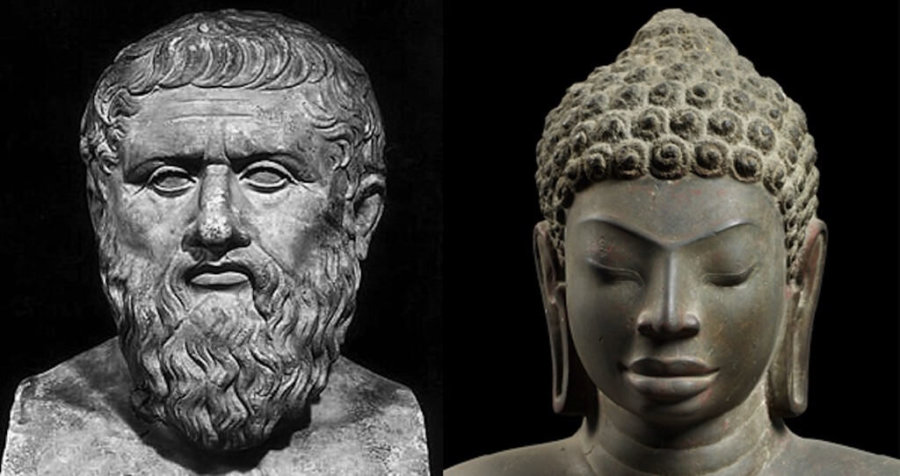

It is in a climate of conventional triumph, or of silencing of all dissent, that Convention is the falsest; so much so that many an intellectual will be readily tempted to seek truth elsewhere than in the conventional world. Just as the pre-Socratic “naturalists” that Aristotle subjects to critique, or as the anchorites that Buddhism’s Prince Siddhartha questions upon discovering that truth is not something to be sought outside of the illusions of Convention, but at the heart of Convention, as the very poetic mind producing conventional illusions. Whereas some are tempted to reject conventional life as unjust, or based on masters’ deception of innocent subjects, the enlightened Siddhartha, no less that the Socrates of Plato’s dialogues, sees popular deception as willfully accepted. People have a common need for lies, especially the noble or ennobling fictions upon which are built entire nations. Life without lies is unlivable, as Leopardi, in the wake of Giambattista Vico, taught well. Man might have fared well without fictions in the Garden of Eden, but not ever since he had dared to look outside of it in search for truth. He had thereupon been compelled by fear of infinity to conceal his nakedness before the dark. Thus would it be that, so to speak, a fig leaf would stand as the founding element of civilization.

The realization that human society is founded by necessity upon fictions that people both need and cling onto, stands at the basis of the pre-modern rejection of the very idea of freeing people of all illusion, or of guiding them into a new “demythologized” world of unprecedented “objectivity”. This scientistic dream in which a single logic could dominate impersonally over our whole lives, or in which no aspect of life would be left unchecked, was not taken seriously by pre-modern men, since they lacked any technical means to give it popular credibility. Today, technology offers tyrants the unprecedented means to persuade entire populations that we can all live by a single discourse constituting a fortress of sorts against any openness to a transcendent life and discourse. This is not to say, of course, that the dream of absolute immanence is realized, today, as if postmodern man had actually entered into a world beyond superstition, a world in which we count only upon what is eminently practical. Quite to the contrary, postmodern man lives almost entirely for what is most vain, namely distractions and the labor required to fuel them. What has been realized, today, is rather a worldwide consensus that History has ushered into an era of raw objectivity, of naked realism, whereby we can live critically without believing in anything insofar as we are one with the world. Now, this world we are one with is that of stark data, the “information” constituting the ultimate “building-blocks” of the universe. Men themselves, their lives, are conceived in terms of inherently valueless information, “numbers” the loss of which would coincide with our utter demise. Our very identities are supposed to be material for archives, recycled by news agencies according to ever-varying market demands.

No macabre irony is discerned about the easy manner in which our libertarian age has incarnated the abominable compulsion of German Nazism to consider human beings as mere data. At the end of our History—of what we conceive as such—stand masses of human derelicts for which “transhumanism” appears as delightful Mecca.

No wonder classical antiquity strikes us as essentially incomprehensible.[1] It does, not because it must be, but because our beliefs prevent us from hearing any voice that does not accord with that of the logic dominating our times—our own lives.

We now stand at the end, or in the final stage, of the consolidation of the early-modern dream of changing the world. Changing the world is not only assumed to be our most liberal “responsibility” and “moral imperative”; it is also a destiny we cannot escape. We are, so to speak, condemned to change the world. We are, furthermore, convinced that changing the world is what people have always done, even though only we are fully aware of it.

Yet, what if we were not changing the world, at all? What might it mean that we are not? What if classical antiquity were right that we do not change the world, but that we merely order or reorder constituents of a world that remains, overall, unchanged? Let us imagine the constituents of the world as fixed in types and as a totality, but such that we commonly displace some constituents as part of our effort to order, humanize, or civilize areas of the world from within. We could be gathering, for instance, honest men into a single community, rather than leaving them stranded in the midst of crowds of dishonest men. We could be building defense-walls around a civilized community, inviting only honest men to enter, while leaving all dishonest men outside.

This is not quite the moderate vision that classical antiquity preaches, but it is nonetheless a vision that our classics would appreciate, with the understanding, tacit or otherwise, that absolutely honest men are so rare that they constitute an extremely small portion of those who are commonly held as honest, namely those integrated into a city where customs and laws are revered without being mistaken for truth proper.

Our classics saw that there were natural or necessary limitations to political life: human or civil order fails to reduce to itself the sub-human (unconscious or material) motion out of which it arises; much of the “spinning” of matter survives, as it must, in political life, as passions that are never fully tamed. Popular passions may be tamed at intervals, but not constantly. Indeed, as long lasting its civilizing effects may be, the emergence of an Orpheus capable of making stones cry with his lyre, is a rather rare occurrence. It would be unreasonable to expect that political life could be more than an imitation of divine life, or that civil law and order could be more than a poor approximation of truth.

As a poetic imitation, our political situation can be better or worse according to its openness to its self-critical divine model. The temptation to shut politics to the theological or the religious would then amount to the temptation to mistake an imitation for its own model—to mistake becoming for being itself.

Modern man has fallen prey to the greatest of temptations by reconceiving becoming in indefinitely progressive terms, as if becoming as a whole could gather into the unity of being. On the classical alternative understanding of becoming, we climb the ladder of being, out of lesser modes of being to higher, more noble or civil ones, while never leaving inferior steps of the ladder empty. We rise, not from matter to divinity, but through matter to a humanity open to divinity. In this world, humanity or civil life and order as conceived by our classics, and not divinity, is our proper goal—openness to divine unity, rather than divine unity itself. Which is more, by remaining open to divine unity, we awaken to the inherence of the divine in our own openness, finally realizing that the human is that through which the divine finds or envisions itself as end. The fully civil man belongs to a community fully aware that our genesis is not by chance or blind necessity, by being providential: we are born out of the “spinning” of quarks and galaxies alike to fulfill their otherwise hapless spinning in a movement that is no longer outward, but reflective—a concentric one—empty of material pretension, of the illusion of power mistaken for its source. This properly human concentric movement stands as the window through which the divine finds itself, in the respect that it sees itself through man, the divine’s own image. Thought, reflection itself and finally all movement, belongs to the divine, so that it makes sense to identify man with the reflective topos in which the divine reveals itself to itself: man is ultimately the thinking that, while being of the divine, belongs to the divine itself.

What our civilization’s classics teach, then, is not an ascent of humanity to the divine—not a “history” of mankind synthesizing the subhuman and the superhuman, the beastly and the divine—but rather a mysterious ascent of the human to itself, a coming of age of man, as divinely ordained mirror of divinity. Nothing more and nothing less. Whence, again, our classics’ refusal to change the world. What our politically-minded, or awakened classics stood for is recognition of the human world as providentially open to the divine. Beyond this recognition and the illumination of the world’s nature as coinciding with the recognition in question, we cannot rise, and indeed we lose ourselves. Beyond the modes of civility taught by classical antiquity, we simply grow uncivil, or barbaric, even as we may believe to have given rise to societies that are more liberal and sophisticated than what our classics would have dreamed possible.

If, then, for our classics the world cannot be changed, this is because it is what it is supposed to be, namely a mirror of divinity, in which we may or may not fulfill our role of witnesses, as places of divine awakening. The classical representatives of pre-modernity reject any societal attempt to conquer the world so that the world may mirror one people or will among others, not to speak of one system of rules and regulations above any other standard of right and wrong. To show what the world is—to illuminate it—and to thereby contribute to the thriving of properly human or civil society, is the best we can do. To attempt to do better would be to do worse, or to abandon our humanity in favor of a delusion, all the more where the delusion calls us to sacrifice our openness to the divine in favor of worldly success; as if our success could be measured aside from an otherworldly end.

In the best of cases, in sum, present day societies can live up to the best societies of classical antiquity, whereas, at worst, we can betray what our classics stood for, by pursuing the establishment of a society shut to divine transcendence by growing infatuated with its own universal empowerment.

That the best societies of classical antiquity were extremely flawed, is known. What our times forget is that while flawed, they allowed our classics to produce the greatest testaments of divinity we know of. What classical educators focused on was not the establishment of a perfect society, but the cultivation of highly-imperfect societies that would remain, nevertheless, open to divine perfection as manifest through the great monuments of classical antiquity—not least of them, the lives of moral and intellectual heroes. Our societies praise themselves for many a wonder, and yet they stand as dwarfs with respect to our classics, and not even as dwarfs on our classics’ shoulders, but as dwarfs at their feet. Dwarfs who believe themselves giants by projecting upon the world their gigantic shadow.

We are dwarves by having abandoned the classical pursuit of moral and intellectual excellence, as opposed to the modern imposture of excellence, namely the self-attribution of excellence shut to any and all standard above it. This is especially evident in university circles, where the parading of excellence tends to serve as mask of mediocrity.

What has been, above all, abandoned by our age is the classical phenomenological exploration of ideas—not mere “adventures” (Whitehead) of worldviews in the service of the future, but examinations of permanent forms of humanity disclosed as fields of pure intelligibility of totality, or of pure understanding of order as such.

While not trying to change the world, our classical educators did humanize it in the respect that they helped people return to their humanity—to what they were in themselves, to the reason they were wherever they were. How did our classics help the world? By heroically representing or incarnating the ideas or forms of intelligibility constituting the world itself. Change was then always functional, even accidental to illumination. What counted was the exploration of the real (non-illusory) contents of the world, while the attempt to change them would have seemed absurd. The exploration of permanence (permanent forms) ran against modernity’s invitation of a future world-dominant form resolving all conflict between opposed worldviews.

What sets our classics apart from modernity is, above all, their education to heroism, an education reflected in their very representation of the cosmos (universal order) or physical motion as unfolding in the light of transcendence. Thus, for instance, our pre-modern classics do not attempt to establish immanentistic explanations of physical motion, explanations reverting to physical forces (gravity, for instance) as ultimate causes. In their stead, explanations open to transcendence were proposed, so that, for instance, the relation between celestial bodies could be thought of in terms of imitation, rather than of invisible physical forces. In both cases, explanation relies on analogy, yet in the former case we have a poetic analogy, whereas in the latter, we have a mechanical (“abstract”) analogy. For our premodern classics, it would be a mistake to try to understand the physical in merely physical terms. The preferred alternative would be given by a reading of the physical as imitation of the psychic—an imitation evidently falling short of the psychic. Thus, for instance, we may say that a planet follows a star in the respect that it “imitates” a superior being, even as it tends to preserve itself.

A poetic reading of physical motion is bound indissolubly to a poetic understanding of time and space as dependent upon being. Time, here, is a difference between aspects of a determination of awareness or consciousness. Otherwise stated, time is the measure of the separation between two aspects of a thing relatively to the thing’s perfection, or its being-in-thought.

We need to slow down to think of time, of what we mean by “time”; we need to come to a still point, we need to free ourselves of the illusion of being-in-time. We are not ultimately lost in time and time does not pass. We do; or rather, things do, as they show themselves according to their way, their mode of witnessing their own being-in-thought. We may then speak of the “time” of a tree, as the tree’s way to reflect its pure intelligibility. In this respect, time is, as Plato would suggest, the image of eternity. Insofar as we cannot attaint to the infinite perfection of our being, we “move,” so to speak, that is, we re-appear or re-produce in a manner proper to our kind. The course of our re-appearing is our life, somewhat of a dance that mirrors, imitates, or bears witness to our perfection, what the human being ultimately is. Thus, as human beings, we have our own time, that is, we age in our own manner. To understand our life is to read it as an “algorithm” of our eternity or infinite perfection; as a picture begging for interpretation. So, man has his own time, while a tree has its own time, its own way of reflecting its being-in-thought, or its pure intelligibility. If we were faced with no obstacle, we would not move, but attain at once to our infinite perfection. It is the presence of obstacles, as Vico reminds us in his De antiquissima Italorum sapientia (1710), that compels us into motion—and thus, as we have seen, into imitating our pure being. Hence our classics’ presentation of life as a poetic endeavor. As for the question of space, as Aristotle would stress, there is no space aside from a something disclosing it. Space is created by determinations of mind, so that we do not move in space; rather, space is generated by our movement understood poetically as dependent essentially upon a metaphysical perfection or still-point.

In sum, the classical alternative to the modern teaching that we live in space, is the teaching that we generate space by responding poetically to our eternity. Our mode of response to our eternity is proper to our species, defining what is naturally right for the human being as such. Whence the corollary that ethics is the proper door to metaphysics.

There would then be a right way to live for man as man, which does not coincide with the right way to live for a tree, but that is compatible with it insofar as both man and tree are rooted in intelligibility.

No one critiqued modernity’s rejection of classical poetry more systematically than Giambattista Vico, who decried the Cartesian-like overturning of classical education as feeding into outright tyranny. The modern abandonment of classical liberal education would usher into an era of unprecedented violence, inspired in part by ancient foolish quests to possess the heavens. Violent would be the life dedicated to appropriating infinity, or the infinite perfection of our being, rather than mirroring it on the low grounds of poetic-political imitation. Violent would be the project to change the world, i.e. to transplant it onto a new technical-mercantile foundation. Hence Vico’s critique of Spinoza’s reduction of politics to mercantilism. Modern progress is, for Vico, a regress into an obscurantist resolving of ethics into metaphysics, as if political life could ever be the highest life; as if our loftiest aspirations could ever be limited to the present; as if we could rise into the future without falling back into the past.

Vico was especially careful in warning against mistaken views of poetry leading to the eclipse of poetic mimesis by a pretense of indefinite progress, entailing a leap into a true devoid of false, a certainty beyond doubt. We are here at the dawn of modernity’s mathematical “new science” (Galileo’s nuova scienza), which Vico counters with his own poetic scienza nuova, a renewed science, or rather a renaissance or unearthing of science, that does not leave any old science behind.

If for modernity’s new science the man of the present has the responsibility, indeed a moral imperative, to speak with Kant, of converting the past (realm of necessity) into a future (realm of freedom) that cannot fall back into the past, for Vico our piety is bound to our duty towards republican institutions testifying to the poetic nature of man. Vico’s defense of classical piety illuminates the poetic circle of human things (cose umane), where the future is necessarily entering into the past via the present. We are not stepping out of the past; yesterday is not becoming today; we are not, in other words, advancing into a new world. If of any new world we are to speak, that world must be the world as it is always, namely new or present. The “new world” is not in the future, but in the present, as a poetic image, a fiction that, while dying into the past, points at once to the eternal premise of all temporal frames.

It is almost impossible to imagine Vico’s classical understanding of time, as long as we remain bound to or blindfolded by modernity’s progressive conception of time. Is the present not the product of the past? Are we not continuously stepping into the future? The alternative offered to us by Vico’s classics suggests that far from stepping into the future, we are stepping into the past, which will never become present without passing through the future. If there is a present, that is because of the present’s death—the present’s relapsing into the past—for the sake of the present’s resurrection, or re-emergence. Modernity’s present, on the other hand, eschews self-negation in the name of positive growth. Progressive openness to pure transcendence via self-negation, is abandoned in favor progressive affirmation into an immanent shadow of transcendence. Here again modernity offers us a secular replica of the Christian repository of classical antiquity. For, to speak in Christian terms, there is no Resurrection without Crucifixion: the only “resurrection” modernity finds appealing is one presupposing the rejection of the Crucifixion as a disease (psychotic or otherwise). This is not to say, of course, that self-sacrifice is rejected altogether. Modernity proposes a “symbolic” self-sacrifice, a shadow or dream of self-negation that does not carry out self-negation thoroughly. Self-negation is now a merely strategic or methodological formal step on the path of progressive self-affirmation. Self-negation stands as a relatively-risk-free economic investment. We do not thereby risk our worldly identity, or sense of certainty, but merely one or more of its assets, and always for the sake of boosting our “historical” portfolio. To risk the worldly would be, for the modernist or evolutionist, tantamount to risking everything. This is entirely understandable given modernity’s immanentism, or given that modernity’s present is as shut to eternal being as Leibniz’ monad is windowless. For pre-modernity the present depends radically upon absolute transcendence: the present’s roots or beginnings are “high” and not subject to loss. We can then carry out self-negation thoroughly, without negating our raison d’être, which is not a function of our deliberation. Openness to a “reason” transcending our freedom allows us to risk our freedom entirely, without losing it. If reason as such were limited to the reason of our development, or of what Hegel calls “History,” we would never be really risking our freedom; we would merely behave as if we were risking our freedom. Our self-sacrifice would be virtual or self-serving; as with all modern “ideological liberators,” our self-sacrifice would be inebriated with the prospect of our building a new world, ultimately a new world society.

For those of us who are still capable of doubting the progressive narrative of modernity, including its conceptual skeleton sustaining the evolutionary character of being itself, the present is at once open to unchanging being and engaged in a life escaping the progressive, ever-changing dictates of what has been called “the open society”. The present has then a twofold allegiance, whereby it dies ethically by way of resurrecting metaphysically: ethics is, to repeat, our poetic key to metaphysics. This formulation of our present condition is heir to a classical tradition represented most vividly by Plato, in the West, and Buddha, in the East.

For Plato’s Socrates, the hero illuminates the contents of the human world lest this world be conceived, if only unreflectively, as a cave cut off from the heavens of pure intelligibility, of what the human world is in itself. The appeal to transcendence, the pre-Socratic “scientific” departure from or negation of public opinion, is turned backwards, to convert into a quest for metaphysical truth at the heart of human illusions now read in terms of poetic reflections, lest they be obscured in their original valence by tyrants, or rather a tyrannical mentality appropriating and manipulating public opinion as instrument for the creation of a new world, a transposition of the old “cave” into the heavens of pre-Socratic, natural “science”. There we would build a new society beyond common prejudices, or poetry; a purely technical-scientific society of trans-human objectivity, if only one requiring the replacement of old political boundaries (that is, stable laws) with ever-fluctuating mercantile rules and regulations. Socratism stands critically in the way of this modern aspiration inspired by late pre-Socratic science or sophistry, by deflating its rationality with the aid of religious piety, ultimately showing that natural scientists are imposters whose “expertise” is no closer to truth than is that of farmers and blacksmiths. Indeed, for Socrates Sophistry’s “science” stands as the consummate imposture, since it pretends to stand above all piety, or republican duty. Natural science’s call to universal responsibility—what for Kant will be our “moral imperative”—to rise into a trans-political society, is, for Socrates, nothing but a fowl distraction from genuine piety.

What Plato’s Socrates taught in the West, Buddhism’s Siddhartha taught in the Far East, inviting a return to human communities as sites of awakening to ultimate reality. Siddhartha’s early “scientific” negation of the human or political in favor of the “natural” is merely propaedeutic to Siddhartha’s later critique of the ancestral belief that, to echo Heraclitus, the way up is the way down, which is to say that the way we rise back to our source coincides with the way we descended out of it. Siddhartha, no less than Socrates, teaches that the “natural scientist,” as we would call him, is wrong in assuming that he can rise back to metaphysical unity. What we can achieve amounts to a poetic mirroring of metaphysics, a mirroring that corresponds to our very lives, or ethics, since the human being as such lives in dialogue with others.

When the young Siddhartha departs from his regal cocoon in search of genuine awakening or truth, he sees that most if not all of his compatriots were lost in a state of moral and epistemic sleep. They were, so to speak, living-dead, drifting as ghosts in a world of illusion. Siddhartha’s return to his people signals a deep recognition that his people are not originally lost in a daydream; that human beings as such are open to awakening, even as they live in ignorance. Their ignorance of ignorance, their drifting in oblivion of their condition is a corruption that can be countered by a good education. Thus does Siddhartha emerge as Buddha, the awakened educator, the one who teaches that all of what we cherish is, literally, empty. All of our certainties are dreams. Even and especially the certainty of being free is a dream.

As with Plato’s Socrates, Buddha does not write; his students write down his lesson concerning ignorance, or the emptiness of all human certainties. The lesson is not meant, as postmodern self-proclaimed Buddhists would hold, as an invitation to reject transcendence or ultimate awakening; it is rather meant to orient us towards it, in full consciousness of our incapacity to possess the divine, or to live aside from illusion. In Buddhist terms, nirvana, the extinction of all illusion, takes place within samsara, or the rehearsal of illusion. Buddha does not, then, ask us to abandon commonsense, but to see it as an empty mirror of transcendent truth, lest we mistake the world of our imagination for our home-ground. We belong, we might say, to another world. To evoke terms from the old Buddhist Japanese Tale of Princess Kaguya, we ultimately belong to the “moon” of pure intelligibility. Yet, this “other” world must be discovered here: metaphysics must be discovered within the ethical. Whence Siddhartha’s return to his people and his establishment of a Sangha, a community dedicated to truth in the mirror of ignorance, lest we camouflage ignorance as foundation of a castle of impostures shut to truth inasmuch as they are mistaken for it.

Modernity overturns the Socratic-Buddhist turn, setting out to build a new world of superhuman, “technical-scientific” certainties by having used Socrates to demolish the religious piety he had promoted. Socrates is then turned against himself, or his work is used to demolish its traditional fruits—not least of them, the fostering of reverence towards divine transcendence. Stripped of its openness to divine transcendence, Socratic dialectic would be appropriate as critical basis of a new world shut to divine transcendence. Modernity is such a world, populated, not by people piously recognizing their ignorance before the heavens of divine transcendence, but by people impiously pious, as Vico would have it, that is, bowing religiously to their idols.

Upon returning to us, Socrates or Buddha do not encounter pious ignorance, but impious pretension; people walking, no longer unreflectively, but reflectively in their sleep: people who believe to have become enlightened on critical grounds and who are consequently sworn enemies of anyone doubting their certainties or alleged knowledge. Our “science” or its progress must not be doubted, lest the whole new world of brave modernity fall apart, as a castle of cards. What is more, so as to ensure that the citadel of modern technical-scientific certainties thrive undisturbed by serious doubt, our “scientific experts” have produced a formidable stage upon which they may control all public discourse. The stage in question is the worldwide internet, a telematic net advancing the cause of modernity, while “trapping” all opposition to it, most notably by fragmenting discourse (into piecemeal “information”) and smothering genuinely Socratic criticism under mountains of spiraling distractions luring people to abandon, indeed abhor and condemn the piety of classical antiquity, once and for all.

In sum, upon returning to us, today, Socrates and Siddhartha are no longer faced with pre-philosophical ignorance open to the possibility of philosophy, but with post-philosophical ignorance pretending to incarnate the very consummation of philosophy in terms of a science certain of its course inasmuch as it rejects all serious doubt about its foundations.

Upon returning to us, our Platonic classics face the enmity of populations believing to be changing the world out of enlightened responsibility. Faced with our armies of post-philosophical trans-humans, Socrates and Siddhartha would not try to change our world, but to illuminate its emptiness, our ignorance. They would distract us from the distraction produced or even incarnated by modernity’s or post-modernity’s post-philosophical idolatry, freeing us from subjection to any and all indoctrination, in the interest of both knowledge and traditional religious piety.

Notes

[1] Heretofore, the terms “classical antiquity” and “classics” are evoked to loosely refer to as representatives of what Matthew Arnold spoke of as Hellenism.