John Henry Newman: A Step Closer to Sainthood for a Modern Intellectual

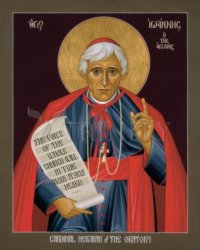

The beatification of John Henry Cardinal Newman by Benedict XVI on his recent visit to England might seem to be a locally Catholic affair. Newman had founded his own Congregation of the Oratory in Birmingham and it was there he lived the last part of his life. His own community and region could be expected to take pride in the advance of one of their own along the path of canonization as a saint. A first class miracle accomplished through his intercession was required to authenticate the papal judgment. That had occurred in the person of Jack Sullivan who had been cured of a spinal disorder.

But there was something more unusual about the event than even that impressive claim suggests. It was that the Church had found a candidate for canonization who fits the mold of a modern intellectual. It is an event of significance both for the Church and the modern world. From the side of the Church it is that all too rare recognition that intellectual accomplishment is entirely consistent with its spiritual mission. This is not to suggest that the Church over the past two centuries has lacked individuals of great intellect and learning. But they have tended to become such within the ecclesiastical setting itself. They have been intellectual leaders within the Church, not necessarily leaders within the intellectual world.

Newman, by contrast, was already a formidable force before he joined the Catholic Church. He had made his way through the loosely Anglican setting of Oxford University in the 1820’s, but his reach extended well into the whole enterprise of modern university life. Indeed, Newman never really became a leader within the Church, despite the Cardinal’s hat, for his independence of mind jostled uneasily with institutional caution. In that sense he remained true to the community of the mind, just as he sought to remain true to the community of faith he embraced.

From the side of the modern world the elevation of a bona fide intellectual to the rank next to sainthood is even more extraordinary. This is, after all, not the thirteenth century when membership in a university coincided with membership in the clergy. It is rather that opposition to the Church is a sine qua non for establishing one’s intellectual independence. The Enlightenment displaced all spiritual authority in the name of free rational inquiry.

Disputes between religion and science that have roiled modernity since its beginning have demonstrated the impossibility of ever harmonizing them again. Newman was among the very few with the credentials to undertake that apparently impossible task. His efforts in this direction may not have met universal approval but he never sought to win an easy victory over the secular age that only his coreligionists would applaud. What he sought in uniting reason and faith was an integration that both sides could embrace. Neither would have to abandon or modify its principles. Perhaps it is that fidelity to truth above all that is the real mark of sanctity Newman bears.

He showed that the great intellectual openness that drives the whole modern enterprise is not so far from the faith that continues to form the community of worshipers. Some measure of his achievement is that his works continue to be read within secular disciplines that hold no brief for any theological tradition. Nowhere is this more evident than in the continuing influence of the series of lectures he gave between 1852 and 1854, published as The Idea of a University. They have achieved the status of a classic within a field, higher education literature, that has produced few enduring statements of its own enterprise. Within the innumerable invocations of the value of a liberal education, Newman accomplished the rare feat of explaining what it is and why it is uniquely valuable.

His Idea succeeded where a million college websites and commencement addresses failed because he was unafraid to state the case forthrightly. That is, that liberal education is useless. It is justified not because it equips us with the skills needed to succeed in more practical affairs, but because it forms the whole person without whom all other achievements lose their value. A human being is an end-in-him-or herself.

Liberal education is what enables the person to understand who he or she is in relation to the whole order of things. It is emphatically not about the narcissistic self but about that enlargement of self that allows us to contemplate our place within a life that is always more than our own. In this respect a liberal education cannot shy away from the question of God, not as a sociological phenomenon, but as the most decisive question we confront. To shrink back from that reflection, Newman explained, would not just dislodge the role of faith. It would unhinge the life of reason that would now have to search for alibis for its own act of self-suppression. Theology has a place in liberal education, he boldly declared, not because it is entitled to it, but because liberty demands it.