Essays on Writing In The Between: Poetry As The Key to Education (Essay XIV)

Essay 14: System and Vision

My modest proposal for poetry —- that it be recognized as the center not the margin of public education —- is based on a long study of the documents, theory and practice. For the purpose of this series of essays I have kept theory at a minimum, preferring to open the reader to the mysteries of the craft of poetry. But in retrospect touching on some more general points may lend enchantment to the view.

Two themes that educators don’t seem to like, having convinced themselves that being honest about poetry will turn off students, are system and vision.

The first term, system, is already central to contemporary phenomenological poetics because the leading thinker is honest about it. William Desmond, whose attention to the details of the experience of poetics is unmatched in breadth and depth, is open about the influence of system. That is because the topic is a branch of the study of being, and being is irreducibly Metaphysical, and metaphysics, as everybody knows, is systematic.

Which is part of the problem with poetics. System building crashes into the profound essence of the matter, which we, following Desmond silently, have called “equivocity,” or the fruitful chaos of immediate, everyday experience. In the meditation on universal impermanence (another borrowing from Desmond), equivocity is key.

A sense of order arises when we look at the evidence, the myriad discourses on poetics, from the ancient Greeks, through the Chinese Daoist thinkers, into modern times. And the poems—- above all the poems. From our study of poems we derive the symbolic terms “warp and woof” to suggest the irreducibly double structure of poetic texts. That doubleness includes doublets such as universal and particular, structure and flow, background and foreground, etc. A system grows like a living coral reef. It’s the conversation, stupid!

Here’s another: structure and vision. The ultimate value of poetry to human being is as a witness to happenings that are otherwise at risk of instant oblivion in our materialist culture. Our senses take in, as part of the universal impermanence, flashes of otherness. As we’ve seen in our accounts of individual poems, the implications of those nonce happenings are spelled out in the narrative of the poem. Think of Boland’s night kitchen in “Contingencies.” The delivery of that vision at the end of the poem is the point of the poem.

Despite the fashionable nihilism which has dominated our conversations about poetry, poems are not meaningless. However important the “negative” defense of poetry has been —- and it has been and continues to be central —- there is a positive pole in our dynamic experience of poetry. Let’s call it vision.

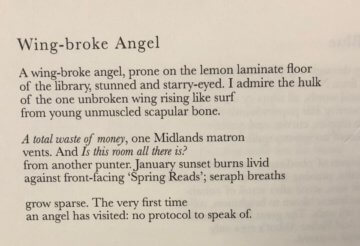

A vision or a thing? We come upon this poem in a magazine, Poetry Birmingham Literary Journal, issue 2, Winter 2019. The kind of place you’d find such a text. That said, the vision bears the traces of its temporality, not just the expert description that complicates our sense of its visionary quality, but also a frankly unbelievable out-of-time aspect, because in our very temporary world, angels don’t figure.

But maybe it’s a metaphor for something else. After all, this is a literary magazine you picked up as you browsed the magazine rack at the local library, which itself is at risk.

The setting of the poem is a library. The “I” of the poem is THAT sort of person. The poem goes on to show that other patrons find the angel on the floor a waste of money—-so maybe it is a “work of art” by a local sculptor. Anyway, the poem describes what the poet likes about it: “the one unbroken wing”, that’s admirable! The full image (“rising like surf / from young unmuscled scapular bone”) has a touch of the erotic in its innocent fleshiness.

The poem, which is by Geraldine Clarkson, turns out to have a double focus, the mean-spirits of the public and the fallen angel. The angel is the key, it provides the “condition of the judgment in the judgment.” That is, the more general topic, the degraded public, is judged by the angel: the poem is a judgment but we are made part of the jury and know the “condition” that determines our judgment of the public.

So the point of the poem is to submit yourself to a complex process. It involves a fallen angel. As a casual reader, you resist. But that resistance may be overcome by the situation in the library. Then there’s the angel, flesh of our flesh. As you consider the many aspects of this poem, you build a tolerance for the otherness of art. And that is also the point.

The poem brings the reader into the orbit of strange and intimate being. The complex beauty of the poem holds her there. It’s all part of her education. She only half understands the poem. She sort of likes the vision. Even though she doesn’t believe in angels, fallen or otherwise. As the closing words of the poem say, the appearance of the angel on the lemon laminate floor of the library was a first: there is no protocol for how we should behave. The poem suggest we behave badly towards the angel. Could the angel “symbolize” something at risk in our culture?

Poems deal with firsts. We need a theory that allows for firsts, a theory of “abstract” being and sensuous, fleshy beings like us. When you think about it, you can’t have one without the other. Ontology is the knowledge—- the logos—- of Universal being. It comes first, before singular beings. But you can’t have one without the other.

Vision and system (ontology) go together. We need a poetics of their togetherness.

References

Bringhurst, Robert. 2008. The Tree of Meaning: Language, Mind, and Ecology. Counterpoint.

Desmond, William. 2016. The Intimate Universal: The Hidden Porosity Among Religion, Art, Philosophy, and Politics. Columbia University Press.

Lu Chi. 2000. The Art of Writing. Translated by Sam Hamill. Milkweed Editions.

Tu Fu. 2020. The Selected Poems. Translated by David Hinton. New Directions

Also see Essays on Writing In The Between: Poetry As The Key to Education (Essays I-V), (Essay VI-VIII), (Essay IX), (Essay X), (Essay XI), (Essay XII), (Essay XIII).