Hedonophia

Sometimes, a suggestion from the crowd, though of little merit in itself, may stir those who are wiser to correction and emendation, and so initiate the subsequent creation of something really worth while.

One might imagine a scene from the Paleolithic:

Younger tribesman: Say chaps, I’ve got a smashing idea. Tonight, when we’re all sitting about, why don’t we sit around a pile of sticks? It’ll add focus!

Other tribesman: nggggggawwwwwa.

Gnarled and wizen elder: Wait a sec, lads. Ogg may have something. But look here, why don’t we set the sticks on fire!

Frenzied cheers and banging of rocks.

So now, with this hope, we offer a proposal way more modest than anything devised by Swift.

There is, we humbly suggest, a case to be made for the development and promotion of a new science that we might call hedonosophia, or Vergnügenwissenschaftlichtheit, or The Science of Philosophical Pleasure.

The impulse toward this is a conviction on the part of the writer, a conviction of long standing, that we are not having the fun we ought to be having.

This requires immediate explanation. It does not mean, God forbid, that we have been avoiding a second drink or missing out on something on the television.

It does mean that there are and have been opportunities for respectable pleasure in the daily operations of life that we are failing to notice and profit by.

Take three cases: washing dishes, learning verb forms, and riding on a subway car.

In all of these necessary chores, there is a strong tendency to focus on the end to the exclusion of the process. We want to get the dishes done, have the verb forms fixed in our minds, and arrive at our destination. We are so teleological it would make Aristotle blink.

The actual doing of these things, the washing, the learning, and the sitting, is therefore reduced to fuel to be burnt for the sake of the accomplishment. We are like a rock climber so focused on the summit that he or she is impatient with the actual climbing.

Now this is unfortunate. If there are points of enjoyment to be had (this is one of the assumptions of our proposed science) it seems a shame to miss them. Heaven knows there is plenty of the other sort of experience.

Further, if there was a method, a practical science, of getting pleasure out of these jobs, would it not make it a lot easier, a lot easier, to do them, and to do them well? That has to improve the bottom line, our precious telos. Imagine if you learned a way to extract possible pleasure from staff meetings!

What would be necessary for such an episteme?

First of all, we would need a protrepticon, a philosophic exhortation.

We must offer a reasoned case to the prospective student, that what we are proposing is good, practical, and of profit.

This, oh my brothers, would be no piece of cake. There is so much new-age nonsense out there that we must expect a high degree of cynicism. Also, there is a meme in our society that identifies being wretched with moral worth. Again, and even more difficult, an openness to the pleasures of the cosmos, which is what we would like to encourage, requires an openness of the heart towards that cosmos, and that is very difficult.

Second, and this is the meat of the sandwich, a method. As far as we can see, this would have to have three parts, at least.

A set of assumptions. These might include (among others)

That there is a Good.

That the universe is good.

That we, and our operations are part of the universe.

That good in the universe is chiefly recognized by pleasure.

That pleasure from good should be maximized.

That human beings are psychosomatic unities.

Next, a deductive technique for recognizing on all appropriate occasions, the good that is in operation at the moment. We suspect that this might involve a set of heuristic questions that the student could learn and apply. The importance of having a more or less clear technique already to present to the student should not be underestimated. This science, if it were developed, would be for those who are stressed, tired, discouraged and angry. It needs to be made as definite and simple as we can. Generalities are very nice, but a clear one, two, three plan of attack would be a lot easier. Nothing forbids the student from developing his or her own approach after the good of this science becomes patent.

What we want, is for the man or woman who is doing the dishes, or sitting in the staff meeting, to be able to say: this is pretty dull, but notice how each plate as it is cleaned is a pleasure, notice that this meeting is an example of voluntary human interaction, worthy of Chekhov. How many faces are there on this subway car. How does the divine good shine through each?

Third, an action plan for establishment of a habit. Anyone who has tried to learn a language from a reference grammar knows that it is useless. Learning anything requires small bites and frequent practise. In such cases, of course, a guru or sensei or Magister, would be best. But that’s not going to happen in 99.95% of the cases. So we need a learning and practise plan. Would to heaven Aristotle had provided one for the Metaphysics! If this involves keeping some sort of diary of one’s progress, so be it. Pride doesn’t come into this.

Some of you are waving your arms and bouncing in your seats. So let’s have a few objections.

1. Shouldn’t this be an art, not a science?

We would call it a practical science, a science because it flows from assumptions, and practical in that it aims to alter conduct. Nothing is actually made here, and that precludes an art.

2. You have a damned chilly idea of fun, sir.

Not at all. First, because many or most of the experiences we are discussing are physical, we would have to pay attention to sharpening our physical perceptions. If we are going to be looking at the universe, we had better learn to see.

Two things get mixed up here, perception and estimation of relative value.

The writer, for example, is in no way a connoisseur of beer. In fact, he cannot tell two brands of lager from each other. But, supposing that he were to sharpen his palate enough to distinguish flavours, then, having recognized this difference, and noted it with pleasure, it does not follow that he or anyone else should put much relative importance to the fact. It is a fact, and so it is of value, but not a big fact, or of great value. Virtus est ordo amorum.

More deeply, the science proposed does aim largely at intellectual pleasures. So where is the quickening of the pulse, the golden glow? It will not, perhaps, be noted on all occasions. But, on the assumption of psychosomatic unity, it need not be absent. Intellectual matters may arouse the most vehement physical reactions. Remember the mathematician who, in explaining how he solved Fermat’s whatsit, burst into tears.

3. This science seems oddly Pollyannaish. There’s a lot out there that is not worth enjoying.

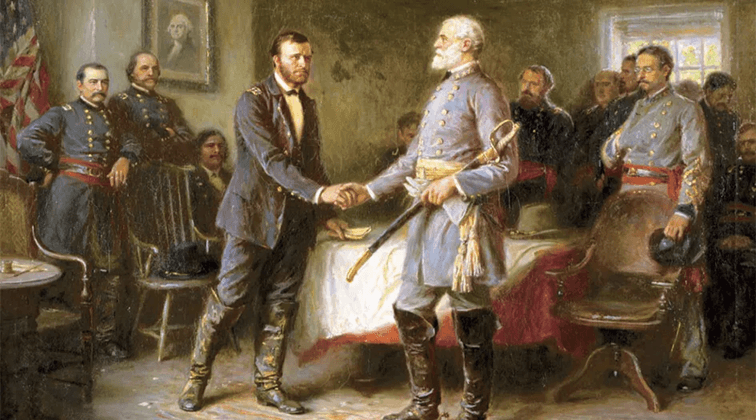

Thank you, Dean Swift, we agree with you entirely. There are many, many, things that it would be impossible to enjoy and vulgar to even try, among them wars, plagues, intellectual stupidity, famine, and slavery.

It is necessary for all men and women of good breeding to recognize what is essentially evil, to name it, and to fight it, if we can. In fact to reliably recognize these situations would be part of the method.

That said, there are a lot of phenomena that are mixed, for example subway commutes. The writer is from Toronto, where the subways are…famous. We do indeed have to put up with what is bad about this (crowding, gloom, bad air) and there is no point in fooling ourselves. But the situation may have points of pleasure as well, and to recognize this will at least alleviate the whole depressing business. Our science would aim to maximize reasonable pleasure, not to make life a continual ecstatic bliss, which would be difficult in this vale of tears.

4. This is just Epicureanism reborn.

We would argue, with deference, no. Epicurus was a materialist and our science hangs, or would hang if it were developed, on the assumption of a transcendental good. Epicurus was as moral as anyone would like, but he founded morality in a calculus of pleasure. Our suggested science would found it in Existence. We are pretty sure of Existence.

5. All this enjoying yourself is low.

Why stay at the party if you’re not willing to have a good time, as far as possible?

What can we say for a peroration?

The author would like to be able to work this out in detail, but finds himself too disorganized intellectually and probably too crabby. But he appeals to the brightest and best among the readers to give the notion some serious thought. There might be a book in it! There might even be money in it (which you would defer, of course, in a lofty and disinterested way, to a local charity).

There are all kinds of sciences, some large, like physics, some narrow, like papyrology. Would this be the least useful among them? Would it not soften hearts and elevate thoughts and, perhaps increase benevolence?

We conclude by wishing our readers the very best holiday season and upcoming year.