Is God Omniscient?

The Person shares in the Divine as being made in the image of God. We too are free. We are co-creators with God; He in His macrocosm and we in our microcosm.

What it means for us to be made in the image of God is not self-evident. Berdyaev’s philosophy explores what it might mean and takes it further than most.

Perhaps we underestimate just how many things we have in common with God.

Berdyaev agrees with the mystic Jacob Boehme that God emerges as Being from the Ungrund whose nature is complete Freedom. Freedom is more fundamental than love, or goodness. It is their precondition. The Ungrund is beyond concepts and rationality.[1]

The Ungrund is that from which God as a being, as the Creator, emerges. As Berdyaev writes, tautologically, the Creator does not exist without the created, God as love does not exist without the loved. God the Creator emerges simultaneously with His creation. God and Man create each other in this sense. God the Creator is the Logos responsible for cosmic order.

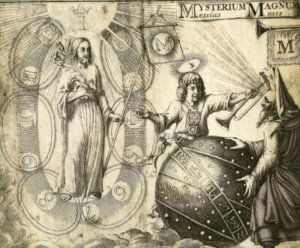

God the Creator is a Person with properties and so is accessible to the cataphatic tradition, i.e., what is expressible in positive concepts. The Ungrund, on the other hand, is the Great Mystery which has given rise to the apophatic theological tradition that operates in terms of via negativa only – describing only what something is not.

A Person, whether human or Divine, has this infinite depth reaching into the Great Mystery and but knows only what enters consciousness. The Divine Creator makes creatures with genuine agency, and thus free of causal determinism, via the Great Mystery, making us, too, inscrutable.

Creativity takes something from the realm of the unknown and mysterious, and turns it into order whereupon it is objectivized,[2] made known and becomes an item in the objective realm. Spirit gets objectivized but its true reality resides within the subjective which retains its inherent connection with spirit. The world of objects can only be a symbol for spirit and the sacred – like a mighty cathedral, or the visible portion of a person, a crucifix, or a cross.

If the universe were only physical, then all would be locked in a deadly determinism. Love, hatred, friendship and enemies, goodness and evil would not exist.

The objective is the known, light of day, and in a sense, dead. The joy of creation is the transition from mystery to objectification.

Many actors claim that having made a movie, they never watch it again, ever. Many musicians never listen to an album once it has been recorded.[3] In both cases, the person has moved on to new projects rather than walking around in a self-created museum of the static.

Fulfilling human existence partakes in creativity. Every good conversation with oneself or with others is spontaneous and nonformulaic. We improvise as the situation demands.

Nothing is more boring than the entirely predictable. Someone whose mind is possessed by ideology becomes a follower of the party line. His creativity is stymied. A pamphlet summarizing the latest zig or zag of the party line is as interesting as such a fellow and can easily be used in lieu of him.

Creativity by its nature involves surprises. Friends surprise each other. Part of this is the result of growth, change, novelty, development, progress.

It is a good rule of thumb not to imagine that humans are in some way superior to God. If people are capable of experiencing wonder and of being surprised it would seem unwise to suggest God is incapable of such things.

Some years ago I accidentally caused a Christian fundamentalist friend to renounce Christianity because in her mind fundamentalism and Christianity were one in the same. In the same vein, I asked a student once if she were Catholic and she replied, “No. I’m Christian.” [!!!] I had argued to the friend that like the story of the Prodigal Son, if my son were to do some great harm, but then to come to me in sincere regret, determined to turn his life around and asked for forgiveness and a second chance, I would give it to him. Hell as eternal punishment, a central feature of fundamentalism, and part of Catholic dogma too, is inconsistent with the notion of forgiveness – assuming that at least some of the occupants of hell would wish to renounce their former behavior at some point in their torment.

This argument is based on the assumption that I am not a bigger man than God, so to speak. Likewise, if I can be surprised and delighted by the unexpected insight or humor of another person, then so can God. Omniscience would render God incapable of such a thing.

Most crucially, however, is that the assertion of God’s omniscience in incompatible with the Ungrund – and thus with freedom, love, goodness and creativity – human and Divine.

Subjectivity has its foundations in the Great Mystery, the Ungrund from whence freedom arises. In creating us, God proves Himself happy to co-exist with other agents, centers of consciousness, choosing, decision-making and purposive entities. Creatures whose freedom He does not interfere with through threats or other punitive devices.

George Dyson, who suffers from the defect of being a mechanist, lover of Hobbes and equator of consciousness and computation, nonetheless recently correctly replied to Sam Harris’ question “If we create AGI, [artificial general intelligence] how will we control it?” that by definition, if AGI is conscious, this means it has a mind of its own, and having a mind of its own means it is not controllable. Somehow Dyson managed this tautology despite being seemingly metaphysically committed to determinism.

The assertion of God’s non-omniscience has to be reconciled in some way with God’s connection with eternity and thus His ability to see into what we regard as the future. But then God’s own ability to be creative has to be similarly reconciled. To know in advance exactly what you will create is to do no more than the equivalent of painting by numbers. Eternity cannot be static. Stasis is incompatible with freedom, love, wonder, creativity, surprise, and novelty. Stasis is death. Eternity can neither be a record of every free choice made, done and dusted, nor a fixed set of all possibilities laid out in advance, like a CD-ROM of a computer game where every alternative choice is already foreseen. Eternity must admit of change.

Kant, also inspired by Jacob Boehme, though to less good effect than Berdyaev, offered what he called a transcendental argument, pointing out that if morality exists, and none of us, other than psychopaths doubts that it does, then free will must also exist. How free will exists remains a mystery. Likewise, here, whatever conception of eternity theologians choose to entertain, it has to be compatible with the Ungrund, which is the precondition of the Person, free will, love, creativity, change and growth in the living God.

Given the existence of an eternal plane, perhaps our “future” selves might be in dialogue with our earlier selves as imagined in Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men.

The mental image that has sometimes come to my feeble mind is of a kind of Milky Way with lights like stars blinking on and off as different decisions are made; the past communicating with the future and the future with the past in the realm of the eternal where neither category exists. But then, “on” at time T1 “off” at time T2 just reintroduces the temporal once again.

This sort of thing goes beyond paradox and defies comprehension – a rod shoved through the whirling spokes of consciousness stopping it dead in its tracks. Change and the eternal seem to need to go together while seeming incompatible.

However God is imagined metaphysically, as a matter of faith and hope, we can ascertain that God loves us, is interested in us and is amused by us. This is made possible because both God and man, through his subjectivity, have a relation to the Great Mystery and realm of freedom.

In the creative act we commune with the Great Mystery and spontaneous imaginings emerge and become objectivized. This is what we are here to do; that and commune with God and other Persons through volunteeristic love.

We have to fight the urge to try to create a formula for creation; to ensure that every effort at creativity bears fruit; to get it under control. Novelists like Chaim Potok or John Irving turn out to have a formula to their writing which quickly becomes apparent upon reading more than one of their novels.

This seems different from the symphonies of Mahler or other composers that in some ways are different versions of the same symphony, not because a formula is being followed, but just because they bear the imprint of the artistic personality of their creator. Those great works of art retain a connection to their Divine origins in a particularly perspicacious manner.

The greatest novels involve a conversion experience by the protagonist and the author who creates in an act of self-overcoming, reaching a new plane of understanding and self-revelation. It is a great shame that Dostoevsky never managed this feat with The Idiot, an otherwise fascinating and first-rate novel. Instead, towards the end, the authorial voice intrudes and he starts discussing the difficulty of creating convincing characters in novels. Successful writing perhaps has that Hegelian dynamic of thesis, antithesis and synthesis.

The idea of omniscience, it would seem, removes surprise and interest from the world. It turns all into Order, the dead, objectivized realm of object, not subject. Subject, since it is free, is unknowable.

God, like Man, lives in wonder and wonder is infused with mystery. If God were ruled by a blueprint in the manner of Plato’s Forms then his behavior would be determined. God evolves. And evolution implies “creative emergence into novelty,” as Whitehead euphoniously describes it.

Is God perfect? Yes. And part of perfection is continued growth and change. A Thai meal might be perfect, but so might a Japanese meal. Perfection need not imply that God is changeless.

A two year old can be perfect little two year old. Human perfection differs from Godly perfection by degree rather than kind. If God were nailed to the cross of a static perfection then we would have killed Him.

God infinitely unfolds His genius in a way not remotely mechanical, in the way that driving through a landscape could reveal one breathtakingly beautiful vista after another. In New Zealand that might mean fjords, giving rise to snow-capped alps, to tree-ferned rain forests next to wild seas; from active volcanoes, to flooded extinct ones; red volcanic rock on cliffs covered in plants with waxy coverings especially adapted to salt-spray, Neo-Gothic university buildings with stained glass Victorian houses nestled in permanently green and lush forest interspersed throughout the city (Dunedin). Each landscape perfect and different from the next.

God chooses not to make his existence unquestionable for that would contravene man’s freedom and turn us into slaves. That is one of Christ’s temptations. It would put God on the side of Order only – the known; and would effectively kill Him. It would objectivize God. We too have an unknown, free connection to Spirit and thus the subjective. We too cannot be fully objective without violating our nature. We too are unfathomably deep – though never fully realized. The Ungrund can never be absolutely exposed.

Mechanists and materialists among us trust in the opposite – that all is in principle explicable. Their desire for the predictable sometimes result in fantasies of a completed psychology and neuroscience which would allow us to throw out all those explorations of the human soul in the form of poetry and, for instance, the plays of Shakespeare.

Martin Heidegger pointed out that Man is not an object. He has a past he remains connected to and he projects himself imaginatively into the future concernfully.

God has a sense of humor. Humor, though mysterious, has an element of surprise. It seems to involve an unexpected merging of incompatible frames of reference; something that makes sense in one context is suddenly thrust into another context where it does not belong. Humor is creative, alive, and requires intuition. A joke explained and made explicit is a dead, unfunny bunch of words.

God changes, evolves and grows. We are made in his image. So do we.

The idea of God’s omniscience abolishes freedom and creativity by turning the Ungrund, into Order and the known.

His commandments (suggestions) would not change, rooted as they are in Truth.

Thinking goes horribly awry when mystery is imagined away. When computer scientists hope to fully explain human consciousness in a mechanistic fashion, they are wishing for the abolition of man.

God creates the living mind-ridden creature with agency, freedom and connection to mystery. His creations retain the duality of subject and object acting as portals of fecundity. Ours do not. They provide evidence of their origins in a non-mechanized realm while still joining the ranks of the mechanical. As Einstein wrote, physics might be beautifully objective but the discovery of these objective principles involves intuition and imagination.

The cataphatic theology of the Logos must make room for the apophatic theology pertaining to the Ungrund. A fully explained or known Person, human or Divine, placed within some detailed system of rationalized thought is a dead Person. Eternal emergence into novelty and omniscience simply do not go together. The living God is a bubbling spring arising from unseen depths and He in his Divinity joins us with this Source which is part of His own nature.

Postscript

A friend has directed me to the book Omnipotence and Other Theological Mistakes by Charles Hartshorne which I was not aware of. I seem to have tapped a similar train of thought in the preceding. The book begins with the following quotations which I admit to finding exciting. However, Hartshorne’s rejection of an afterlife is less appealing.

Some Expressions of the New Theological Perspective:

We do not honor God by breaking down the human soul, connecting it with him only by a tie of slavish dependence. It is his glory that he creates beings like himself, free beings . . . that he confers on them the reality, not the show, of power.

– William Ellery Channing (1788 – 1842)

The fact that God could create free beings over against himself is the cross which philosophy could not carry, but remained hanging from.

– Kierkegaard (1813 – 1855)

I . . . cherish the most certain of all truths and the one that should come first: I am free; beyond my dependence I am independent; I am a dependent independence; I am a person responsible for myself who am my work, to God who has created me creator of myself . . . What a terrifying marvel: man deliberates and God awaits his decision . . . Suddenly, O surprise . . . I have been witness of a change in the bosom of the absolute permanence . . . God, who sees things change, changes also in beholding them, or else does not perceive that they change.

– Jules Lequier (1814 – 1862)

Should we say that because the later God develops beyond the earlier there was a defect in the earlier? But it was no other defect than that which progress to the higher itself determines, and each earlier time stands in this relation to a later time. . . . In this respect the world never advances, because this is the ground of the whole progress, to will something transcending the present . . . and the perfection of God generally is not in reaching a limited maximum but in seeking an unlimited progress. In this progress, however, the whole God in each time is the maximum not only of all the present, but also of all the past; he alone can surpass himself, and does it continually.

– Gustav Theodor Fechner (1801 – 1887)

The traditional doctrines of theology do not solve the painful problem of evil. The ordinary conception of the creation of the world and the Fall turns it all into a divine comedy, a play that God plays with himself. . . . The freedom through which the creature succumbs to evil has been given to it by God, in the last resort has been determined by God. . . . When in difficulties, positive theology falls back upon mystery and finds refuge in negative theology. But the mystery has already been over rationalized. . . . Freedom is not determined by God.

– Nicolas Berdyaev (1874 – 1948)

Appealing to his [Einstein’s] way of expressing himself in theological terms, I said: If God had wanted to put everything into the world from the beginning, He would have created a universe without change, without organisms and evolution, and without man and man’s experience of change. But He seems to have thought that a live universe with events unexpected even by Himself would be more interesting than a dead one.

– Karl Popper (1902-94)

Notes

[1] The Ungrund is also not Chaos, for Chaos is a something, while the Great Mystery is a nothing that longs to produce the something.

[2] See https://wordpress.com/post/orthosphere.wordpress.com/18171 – Chaos and Order; the left and right hemispheres.

[3] Nick Cave, for instance.