Is Miss Brill an Eremofetishist?

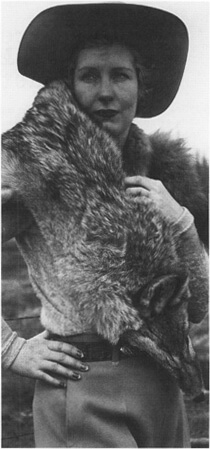

A woman sits on a park bench on a radiant Sunday afternoon. Despite the fine weather (“the blue sky powdered with gold and great spots of light like white wine splashed over the Jardins Publiques”), she is “glad that she decided on her fur . . . Dear little thing! . . . She could have taken it off and laid it on her lap and stroked it.” (This is a time when wearing a fur in public carried no risk of controversy).

The fur is glad too, she feels, to have been shaken free of moth powder and given a good brush and set on her shoulders.

She comes here, to the same park bench (“her ‘special’ seat”), every Sunday, to listen to the concert band and watch the promenade of people at their Sunday leisure. She is attending to the music, the band sounding “louder and gayer . . . like someone playing with only the family to listen,” and she takes a simple satisfaction in its details: “Now there came a little ‘flutey’ bit – very pretty! – a little chain of bright drops. She was sure it would be repeated. It was; she lifted her head and smiled.”

She attends as well to the conversations around her, “sitting in other people’s lives just for a minute while they talked.” And if they aren’t talking she attends to their movements, their parading in couples and groups, their exchanging greetings, buying flowers from the beggar with his tray, the children swooping and laughing, young girls and young soldiers meeting and pairing off arm-in-arm, a nun hurrying by. And behind and around all this vibrant human movement is the park basking in the heavenly day and the sweet melodic music. “Behind the rotunda the slender trees with yellow leaves down drooping, and through them just a line of sea, and beyond the blue sky with gold-veined clouds. Tum-tum-tum tiddle-um! tiddle-um! tum tiddley-um tum ta! blew the band.”

She witnesses another woman, in an ermine toque, rudely snubbed by a man of her acquaintance, and feels not only her own mood but the band’s as well falter with tenderness at this other woman’s slighting, and then, as the slighted woman pretends to have “seen someone else, much nicer, just over there” and patters away, feels herself carried by the band’s resumed ebullience back into the flurry of human action around her.

In a moment of epiphany, she realizes that her fascination in watching it all is no accident. “It was like a play. It was exactly like a play . . . They were all on stage. They weren’t only the audience, not only looking on; they were acting. Even she had a part and came every Sunday . . . She was on the stage . . . ‘Yes, I have been an actress for a long time.’”

And this blossoming conviction that she and all the others in the park this Sunday afternoon, every Sunday afternoon, are a company of actors and actresses on a stage, performing a magnificent play, rises and bears her up to a rapturous emotional crescendo:

“The band had been having a rest. Now they started again. And what they played was warm, sunny, yet there was just a faint chill – a something, what was it? – not sadness – no, not sadness – a something that made you want to sing. The tune lifted, lifted, the light shone; and it seemed to [her] that in another moment all of them, all the whole company, would begin singing. The young ones, the laughing ones who were moving together, they would begin and the men’s voices, very resolute and brave, would join them. And then she too, she too, and the others on the benches – they would come in with a kind of accompaniment – something that scarcely rose or fell, something so beautiful – moving…And [her] eyes filled with tears and she looked smiling at all the other members of the company. Yes, we understand, we understand, she thought – though what they understood she didn’t know.”

And then in an instant, with a simple act of casual cruelty, the illusion of a great communal bond, of her own voice joined in a beautiful harmony, is shattered. A boy and a girl sit at a nearby bench. The girl won’t tell the boy something he’s desperate to hear – scurrilous gossip, or an amorous promise. Thinking the woman can’t hear them, they call her “stupid old thing” and, worst of all, ridicule her fur (the girl says it’s “exactly like a fried whiting”).

And she goes home to her room like a cupboard, bypassing her customary trip to the bakery, and quickly unclasps her fur – the fur she felt so good to have salvaged, having rubbed the life back into its roguish eyes – and shoves it in a box. And she fancies she hears it crying.

I love this devastating story by Katherine Mansfield. It’s called “Miss Brill” – the name of the woman with the fur. I love it because it presents without mockery, with an irony that is thoroughly benign, a person disarmed by the beauty of the world and striving desperately, unwittingly, to subsume her unacknowledged suffering in that beauty. And, of course, being thwarted by gratuitous human cruelty.

And I love it too because of the way it acknowledges the terrible force in the renunciation of a small delight. Miss Brill does not buy herself a slice of honeycake, as she always does on a Sunday, and she can no longer think her fur a dear thing. As much as we are tempted to think an adult should be resistant to such inconsequential privations as an interrupted routine, a foregone treat, a treasured object disenchanted, these are nonetheless an index of acute emotional pain.

“Miss Brill” is a powerful depiction of loneliness, and it shows that to be lonely is to live under a threat. It is one kind of vindication of Thoreau’s observation, which seems to me an unassailable fact, that a life of quiet desperation is the human norm. I believe it would be difficult for any competent reader of the story to deny that it presents a genuine case of cruelty, and that its detailed account of the thoughts and feelings of a particular person in a particular moment is not only psychologically instructive but morally significant.

I also believe that properly appreciating the literary merits and moral insights of this story, which go hand in hand, is incompatible with the view that Miss Brill is an eremofetishist. Here I object to an error that I have myself imagined, but indulge me.

Suppose a lonely person reads “Miss Brill” and discerns in it a uniquely accurate and illuminating model of their own fraught social existence. Miss Brill’s mode of being lonely maps unerringly, they feel, their own experience of loneliness. The personification of a beloved object, the investment of profound emotional energies in that object, is something this person believes is fundamental to their experience of loneliness, a psychological detail that once properly understood unlocks the full picture of themselves as a person living in the absence of meaningful human companionship. They come to see Miss Brill then, with her beloved fur that is in her imagination animated by her own yearnings for and disappointments with human companionship, as a typical eremofetishist, and their own identity as described, revealed, even validated by the application of the same term to themselves. They are, just like Miss Brill, alone (erem-, from the Latin eremita: hermit or recluse), and they fetishize some thing of theirs, that is in the literal sense of imbuing the thing with sacral significance, so that it ceases to be just another inanimate thing, becomes lit with ghostly agency.

(Or suppose simply that they already have these convictions about themselves – that they are, in short, an eremofetishist – and recognize “Miss Brill” as an artwork that lends itself to being understood as a compelling representation of the experience of eremofetishism).

Do we do this person a favor by agreeing to call them an eremofetishist, and understanding the difficulties of their lonely existence as manifestations of a particular social identity and therefore as components of something that is to be regarded as good-in-itself? Are they right to see the moral reality disclosed by “Miss Brill” as delineating a form of (inter)personal identity, a way of being with and toward (or, rather, without and away from) others, which must be embraced if it is to be addressed compassionately at all? I think not.

It is easy to imagine the political mythology that might emerge from a reading of “Miss Brill” with this cumbersome term, eremofetishist, as its fulcrum.

Wearing a fur becomes a way of signifying one’s rejection of human companionship, or rather one’s rejection of conventional forms of human companionship. To see someone in public with a fur draped anachronistically over their shoulders is to surmise that this person believes themselves, sitting quietly alone, to be participating in the great harmonious interplay of everyone around them, even believes that they possess a quasi-paranormal sensitivity to that interplay. Enlightened people insist that these beliefs are to be unreservedly affirmed.

It needn’t be a fur, of course, but a fur is the standard fet. Mofet’s (as they call themselves) have all kinds of fets, from unadorned everyday items to ostentatious craft works. And there are those who adopt fets that are shockingly bizarre, obscene, malodourous, huge and unwieldy, fets that to all but the most staunchly pro-mofet observers seem calculated to cause public consternation.

The metonymy whereby a person is reduced to an item of their clothing takes on new political significance, and any suggestion that it might be crude or dehumanizing becomes politically suspect.

Once lauded views, common among the politically enlightened – “fur is murder”– overnight become reprehensible. Even encouraging lonely people to seek human companionship becomes suspect in progressive circles.

Voicing doubts about the claim to eremofetishism of a highly extroverted person is tantamount to uttering a racial slur.

Metatheatricality is a key term in the theorization of eremofetishism, and the idea of viewing life as a performance, even life’s moments of spectatorship – viewing even the viewing of life as a performance as a performance –, and the ambiguity in Miss Brill’s epiphany (is it dazzling metaphor or bewitching illusion?) works to insulate eremofetishism from difficult questions. Depending on the occasion, eremofetishism can be for its proponents a simple consolatory truth or a vertiginous hall of mirrors, a refreshing act of candor or a protean conundrum.

But of course, it is consolatory. Many people who experience real pain find a common cause, an identity and an explanation, which gives them comfort and hope and a refuge from their chronic suffering. And for that it might all be worth it. The only problem, really, is that it’s a lie. The “understanding” is only grudging assent. The harmony is really discord.

You cannot expect the sheer blunt force of a newborn moral injunction to make people sincerely embrace massive changes to the time-honoured conventions that govern their daily lives. And you cannot expect it to make them true believers in a revolutionary reconception of fundamental features of social life. Miss Brill cannot be famous, or infamous, and still be Miss Brill.

“Most people live lives of quiet desperation.” Distributing megaphones cannot be a solution.