Letter from Vienna (June 2009)

The normally turbid Donaukanal that borders Vienna’s city center has caught my eye today. It seems unusually clear and the sun is actually sparkling off its surface. On the other side, there’s a small group of topless Austrian girls sun-bathing and, nearby, two teenagers who honestly seem much more interested in fish than in bosoms.

Further up the Canal, along its southwestern edge, Vienna’s city center opens up to the visitor. Four blocks away, several streets converge on the large cobble-stoned plaza dominated by the magnificent 12th century Stephansdom (St. Stephen’s Cathedral). Though fans of English Gothic might disagree, the Cathedral’s intricately ornamented towers, ornate tiled roof and blackened limestone exterior are truly breath-taking, elevating one’s thoughts to the glory of God. Architects and artists once used to try to represent His glory through form. They seem to have no such pretenses today.

I walk past this Viennese landmark every morning on my way to work. Even after one year, its beauty still makes me gasp. I don’t know what strange convergence of powers helped me to land a job in Vienna last year. But if God or St. Stephen were somehow involved, I thank them. They have given me an opportunity to live, work and study in a city that seems quite sleepy when compared to other, fast-moving European cities; whose daily Mass (and Confession) schedule for the two dozen Catholic churches in the 1st District alone begins at 6:30 a.m. and ends at 9 p.m.; and whose residents are as conservative—and, at times, curmudgeonly—as they perhaps were a century ago.

Now that the summer tourist season has begun, Vienna is naturally anything but sleepy. But from my third floor apartment, a mere two blocks from the Cathedral, I sometimes happily forget there are hordes of camcorder-wielding, flip-flop-wearing visitors. From the living room window, I can see the onion-domed tower of the building next door and am reminded of where I am. But I hear nothing from the street once ensconced in my den.

* * *

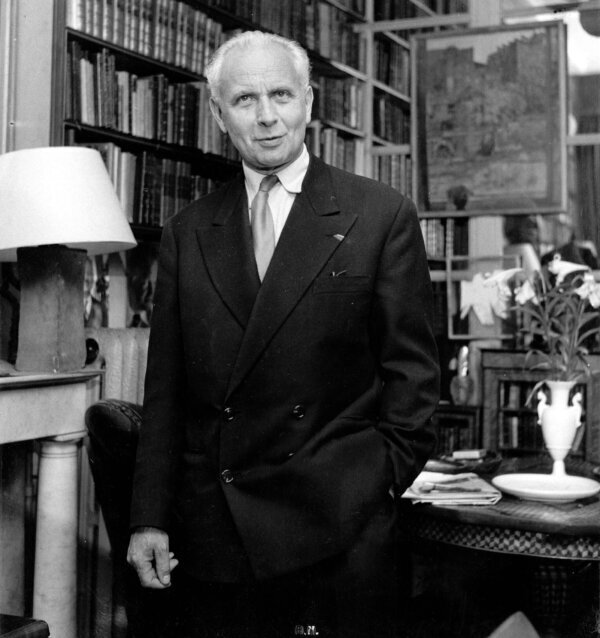

Years ago, as an undergraduate at Dartmouth, I used to dream about visiting Vienna. In those days, when campus life was distinguished by the ‘work hard, play hard’ ethos and my extra-curricular activities revolved primarily around The Dartmouth Review, my academic pursuits continually brought Austria—and the Austrian-Hungarian Empire—to mind. I was introduced then to Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek and Carl Menger, in economics; to Franz Kafka, Robert Musil and Joseph Roth, in literature; and to Ludwig Wittgenstein, Dietrich von Hildebrand and, of course, Eric Voegelin, in philosophy. Strictly speaking, they weren’t all Austrians; but each of their lives was intimately linked with the Austrian capital.

There are some people who insist that the days of that early 20th century intellectual ferment (which clustered around Vienna’s famed coffee-houses) are over. Similar artistic and literary richness in other European cities—Budapest and Bucharest, Paris and Prague – are also said to have disappeared, fading away into distant memories. (John Lukacs’ Budapest 1900 does a wonderful job at describing the turn-of-the-century milieu in that city.) But my experiences thus far in Vienna suggest that there is still room for those interested in high culture and learning for its own sake.

Appearances, of course, might suggest otherwise. Often, late on a Friday night, teenagers flock to the city’s center in search of booze and broads. It is at times like these when I find it quite easy to forget that there are others, like me, who prefer to stay at home with some spicy tobacco and a good book. They are out there. I have met a few of them. There is, for example, an eccentric and well-heeled Oxonian, who serves on the boards of several organizations, helps local Catholic charities and supports several think-tanks. He is always ready for an Italian opera—or simply a nice long discussion about Boethius. Spending an hour with him is akin to attending a private seminar with an avuncular don.

On the street next to mine, there’s a flame-haired and sharp-tongued bartender who studied under the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk and who crinkles her nose when I speak to her about Medieval Scholasticism. (She’s unrepentantly post-modern.) In the autumn, she serves a delicious batch of Sturm, a potent form of fermenting grape juice before it becomes wine.

Sometimes I visit a young Dominican friar who lives two blocks from me in his order’s priory. He studied aesthetics at Cambridge and is currently completing a doctorate in musical theory. We get together for a cup of coffee and talk about life, music, art, while enjoying the stares of the passers-by who are (sadly) unused to the sight of a tall, handsome friar in his habit.

My favorite individual, however, for purely aesthetic reasons, is my personal banker at Raiffeisen. This lovely creature studied international development and plans to do her doctorate in the cutting-edge field of Islamic finance. She is half-French, half-Austrian, speaks to me in Italian and is as gorgeous as a field of spring blossoms under a brilliant azure sky. It’s almost painful to look at her.

In addition to interactions with these wonderful characters, there are also numerous organizations and institutes in Vienna that organize debates and lectures. The Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen regularly invites speakers of international renown. Last summer, Georgetown University’s Jose Casanova spoke about Western secularization and globalization, and in October, the great Italian political philosopher, Rocco Buttiglione, addressed the limited role of the State. In two weeks, the Institut will host Dutch author Ian Buruma, then sociologist Peter Berger and philosopher Charles Taylor, who will discuss the nature of secularism and the crisis of modernity.

Who can honestly say that Vienna is boring? Well, perhaps young people. The city does not seem to have enough discos or pubs to keep them entertained. Having befriended numerous young Austrians and Middle Easterners (the children of diplomats), I know that their hearts and minds are preoccupied with the here and now. They get bored with anything that is not flashy and trendy – or anything that extends too far into the past (or the future). I think perhaps they want more out of life – but insist on looking for it in the ecstasy of the moment, through non-committal liaisons and Dionysian revelry. A few weeks ago, I urged one of them to stay home on a Friday night and read a good book. His laughter still rings in my ears.

* * *

I am frequently asked by some of my American friends what I’m doing over here, so far from the small Vermont town where I was raised. My standard response is that I am trying to learn German (though, of course, there is so much more that I am learning). That is often when one of them will respond, ‘Why bother? Everyone speaks English anyway!’ And, immediately, any lingering desire in me to return to the U.S. will evaporate.

Many years ago, while still at university, we used to sit around and talk about lovely intangibles – about God and man, sin and redemption. We dreamed of learning languages. But we were all idealistic undergraduates then. What did any of us know about the world, the need for a career and the importance of money? We’ve all since grown up in one way or another. And I have long since given up trying to convince others of the importance of learning a foreign language – just as I have similarly given up trying to engage many of my old classmates in conversations about deeper or higher matters.

For the moment, however, the life of the mind is as vibrant and robust for me in Vienna as it was when I was an undergraduate in Hanover. This city—imbued by the spirit of great composers like Haydn and Schubert, and great thinkers like Hayek and Voegelin—has given me a satisfying life.

Vienna is in full relief for me. And while I am nostalgic for those conversations with my old friends , I am reminded, as I pore through my books late at night, of what T.S. Eliot said: “The communication of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.”

Also see his letters April 2010, May 2010, and February 2011.