Letter from Vienna (May 2010)

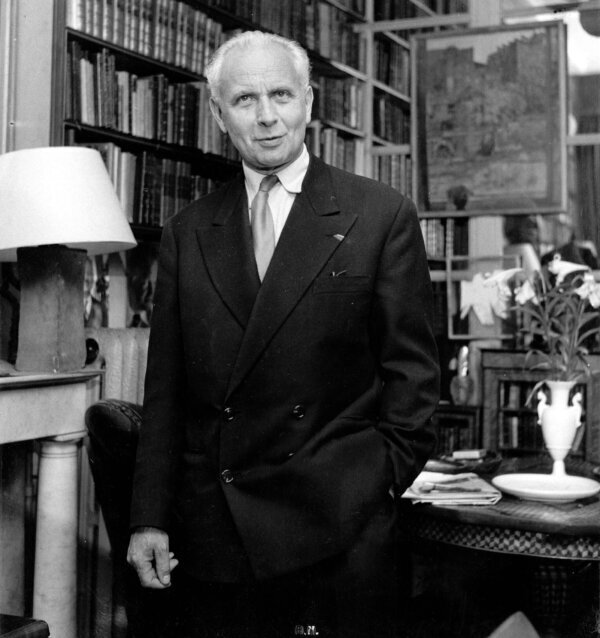

Recently I began to read about the life and work of German philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand who, to escape the Nazis, moved to the Austrian capital — until the German Anschluss (annexation) forced him to leave for the U.S.1 As a conference in Rome at the end of May will consider, von Hildebrand had a lot to say about love; but he also wrote a lot on the subject of beauty — in music, the visual arts and in the natural world.

Yet beauty, like love, is frankly not a subject many of us are used to talking about with any kind of philosophical rigor.

In the past, my own attempts at representing my experiences with beautiful things to others have left something to be desired. I’ve generally described Vienna in strictly physical terms and have tended to limit my comments to rudimentary descriptions of its grand sights and charming sounds.

Frankly, I’m overwhelmed. It seems like every day brings with it a new sensory experience: another tiny, cobblestone street with hidden steps; a previously unseen image of Our Lady on the corner of a quiet building; and the cries and laughter of Austrian schoolchildren on their way home from school.

Admittedly, these are not necessarily the life-changing experiences that the entertainment and tourism industries have taught us to expect when traveling abroad. But they are profound and lovely in their own gentle, hushed way; their worth can only be appreciated when one is not hurrying off to complete an errand. As I’ve told visiting friends in the past, Vienna is a city to be walked. Its delights are to be absorbed and savored slowly.

The truth is that the incredible artistic treasures at the magnificent Kunsthistorisches Museum, for example, simply cannot be viewed in a single day.2 Impatient friends have already made that mistake — returning to my flat exhausted, with sore feet and, sadly, unable to recall anything but a few images. Their experiences proved to me that the law of diminishing returns applies just as well to the viewing of fine art as it does to the consumption of any commodity.

The other truth is that it is precisely in the non-physical realm – in, say, the affective realm — that this city has its greatest impact. Don’t get me wrong: Seeing churches and chapels, visiting the Imperial Apartments at the Hofburg, or meandering through the Baroque splendor of the Nationalbibliothek’s State Hall are all edifying experiences.3 But it is on the inside — somewhere between my heart, soul, and mind – that something indescribable begins to happen whenever I catch a whiff of early-morning incense, walk past a previously unseen mosaic or fresco, or hear the opening arias of a Stabat Mater at dusk.

Nearly every day, when I come to the end of the Graben (one of the high-end pedestrian streets in central Vienna) and the Stephansdom first comes into view, I become breathless. The inadequacies of language make it impossible for me to properly describe what I feel, say, when I see the twin spires of the Votivkirche rising in the distance, hear local church bells ringing at midday for the Angelus, or the clatter of horse-drawn carriages in the afternoon.4 What I am trying to put into words is the poignancy of slipping into the Peterskirche on my way home from work and seeing the Blessed Sacrament, alone and exposed, in a magnificently elaborate monstrance.5

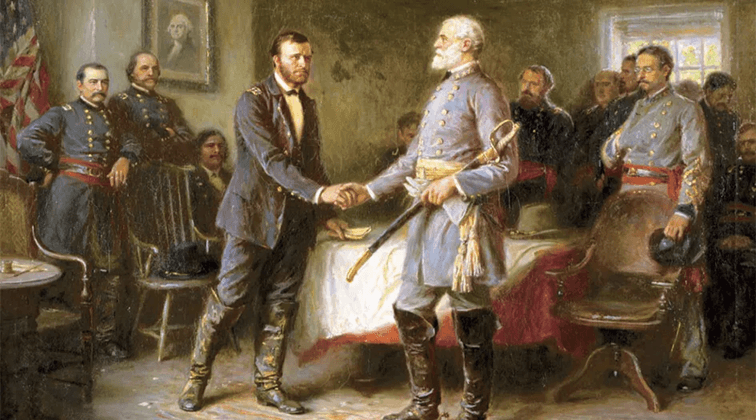

It is not, however, solely religious or Church-related experiences that produce this profound appreciation of the Beautiful and the Good; but it just so happens that nearly everything in this city — with the possible exception of those terribly drab buildings left over from the days of Red Vienna (1918-1934) — seems imbued with the country’s Catholic past. The rise of a more secular Europe during the last century may certainly be a sociological fact, but in habits, manners and traditions, Vienna retains a strong sense of its cultural and religious past – including the Jewish culture that once characterized much of the city’s café-oriented intellectual life during the years leading up to the Great War.

At times I am filled with a yearning to be near something beautiful and good, a yearning that has nothing to do with anything even remotely religious: when, for example, looking out across the Stadtpark in the dead of winter and breathing in the icy air;6 or stopping at the broad, open field of the Heldenplatz on a late autumn evening with the Gothic Wiener Rathaus (Vienna City Hall) as a backdrop; or perhaps simply when strolling through an early morning fog, under wrought-iron lamps and battered wooden doors, along some forgotten backstreet of the Innere Stadt.

Something mysterious seems to happen when I experience these things; it’s almost an aesthetic kind of ecstasy. Perhaps in time, as I learn more about aesthetics from von Hildebrand, I’ll find more formal ways to express my reactions and responses to my Viennese environment. But a little part of me will always remain feeling like a provincial, looking upon this city’s marvelous treasures as a barbarian might have looked upon a copy of the Gutenberg Bible.

Also see his letters June 2009, April 2010, and February 2011.