Philosophy and Philosophy

In recent months, I’ve been reading books that — if I weave them together — bestow overviews of two major branches of philosophy: Analytic Philosophy and Continental Philosophy. They have dominated the field for the last hundred years.

I’ve heard contributors to each branch say of the other, ”It’s not philosophy.”

Oh well, let’s not quarrel.

So, let me tell you what I‘ve learned about these two major types of philosophy. It’s something of a detective story: Who-dunnit, and with what motives?

First, take the Analysts. There were figures like Bertrand Russell and Frank Ramsey in England, Ludwig Wittgenstein in Vienna and Cambridge, Carl Hempel and Hans Reichenbach, philosophers of science, Rudolph Carnap, a founding thinker in “logical empiricism,” Otto Neurath, another of the founders, and co-signer with Carnap of the manifesto titled, The Scientific Conception of the World: the Vienna Circle.

I won’t go farther down the cast of characters, but they included many of the foremost thinkers whose concern was to ground twentieth-century philosophy in the world of verifiable fact. They did not want illusions. It was a post-Darwinian era, an age of Freudian psychoanalysis, of Albert Einstein’s relativity theory, of Werner Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, and these early Analysts wanted to make philosophy as clear and unambiguous as the break-through sciences.

Philosophy was not science, but they wanted it to show us how to keep clear of nonsense and to speak as meaningfully and truthfully as the scientists were doing. They began by supposing that the way to make speech refer meaningfully to reality was to correlate it with basic bits of present experience, whether these bits were to be deemed things, or facts, or states of affairs.

What these same thinkers began to notice, however, was that many meaningful statements could not be correlated with such basic bits. For example: statements about the past or the future; statements about the unobservables of physics — like atoms or electrons; cosmogonic hypotheses — like the Big Bang theory of the universe’s origin; statements that were merely probable; and statements about right and wrong. In fact, the verification principle (that a statement was meaningful only if there were criteria for verifying it) could not itself be verified under those terms!

For all their narrowness, it is very much to the credit of these early Analysts that they themselves uncovered the flaws in their own methods. In that above all, they showed their fidelity to the scientific spirit.

There was one feature of reality that these thinkers had not made room for. In the 1920’s and 30’s, many of them lived in Vienna. They were known as the Vienna Circle. Many were Jews, or half-Jews, Jewish converts to Christianity, or descended from converts. Their philosophy had no concern with this fact, but — after the loss of the polycultural Austro-Hungarian empire — Vienna did. Now Jews were no longer parts of a diverse cultural matrix. They stood out – they even had a certain cultural preeminence — and it made them a resented target.

Those who could flee, found safety and work elsewhere, mostly in the universities of the English-speaking world. Over time, they and their students modified and enlarged their notions of meaningful speech and criteria. Their early respect for clarity and evidence remained a valuable legacy for Analytic philosophy.

But what about those very political and social upsurges that had swept so many out of their native places and – for many – out of their lives? The early Analysts had lived in the timeless space of logical truth. History had overtaken those spaces. Was history of any interest to philosophy?

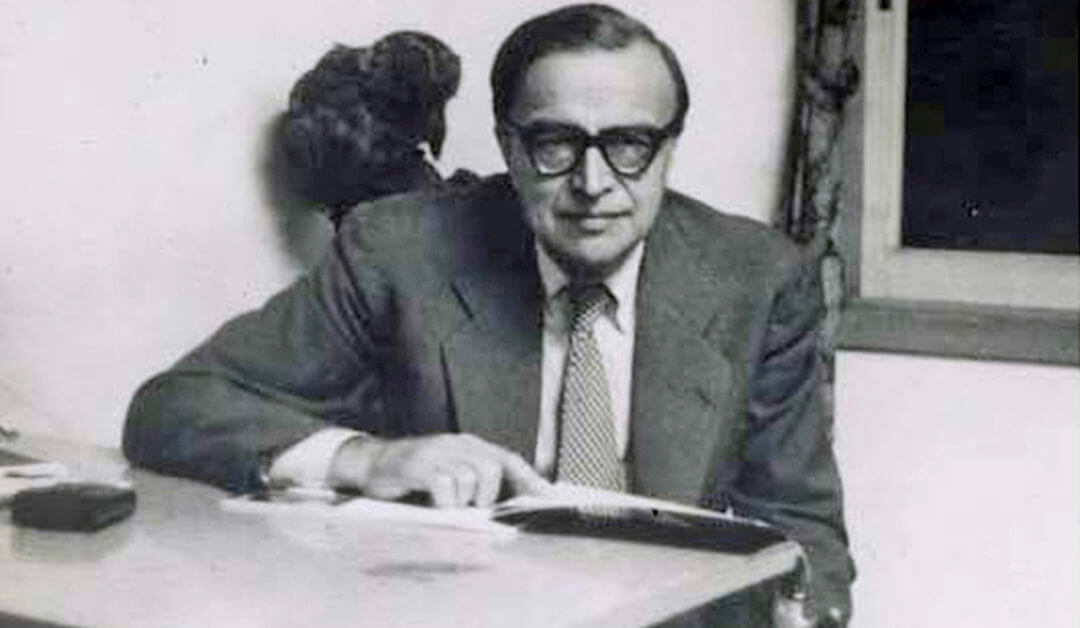

Yes, but to a different branch of philosophy. We turn now to the Continentals. Here, there is a lineage to trace. G. W. F. Hegel [1770-1831] had done more than any other thinker to make history itself a subject for philosophy. Hegel’s influence had waned with the progress of the new sciences of the twentieth century, but was given a second birth between 1933 and ‘39, in Alexandre Kojève’s lectures at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes.

You probably never heard of Kojève. But his influence, as his lectures were collected and published just after World War II, permeated post-war intellectual life in France and, eventually, the wider cultural world.

Let me give you the gist of it. The published lectures have the title, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel. It’s an account of how human beings become actors in history. As we first come upon them, human awareness is satisfied insofar as animal appetites are satisfied. Why isn’t that enough? What’s left over — beyond animality? Well, that’s exactly what human consciousness itself wants to know. Beyond animality, who and what am I? Since the answer isn’t already in hand, it must require some action, if I am to find it out. Who or what can tell me who or what I am?

It seems that only another consciousness could give me an answer. My identity could be established in comparison with another’s. But what we each want from the other is preeminence. Let’s fight for it. Yipee! I won! Oh poo. He’s dead! Now he can’t tell me that I’m the best person. Next time, I better let my rival live and serve me. That’ll secure my preeminence. Except that it won’t, because a consciousness in that degraded position has insufficient standing to be credible.

As Kojeve explains Hegel’s view, the stages of history unfold, with one Master/Slave relation after another, each one tried and found inadequate. Finally, history can come to an end, when the human being comes into political reality as citizen — recognizing other citizens as peers, endowed with equal rights by mutual agreement.

Of course, details, and the finer phases of this dialectical narrative (from Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind) can’t be filled in here. Foreshadowed in Kojev’s lectures we see presentiments of the current talk about Same and Other, Oppressed and Oppressor, showing up first in French existentialism, along with the neo-marxist rhetoric of equality, and eventually in all the varieties of post-modernism.

I never taught Kojeve, but I did teach Hegel’s Phenomenology, including his Master/Slave dialectic. When I taught that chapter, I contrasted it unfavorably with the account of history’s beginning in the Biblical Book of Genesis. I thought it was less true than the Cain and Abel story.

As you may recall, Cain and Abel are the two sons of Adam and Eve. We first see them after their parents have been expelled from the Garden of Eden, the pre-historic paradise. Each man then offers his own sacrifice to their Creator. Cain’s sacrifice is rejected. Abel’s is accepted. So Cain kills Abel. That’s the beginning of history (and its recurrent theme) as the Bible tells it.

What does the story mean? We human agents must make some sacrifice, give up something – if we want to get anywhere in our lives. Let’s say the first guy figures out what to give up. For the second guy, his sacrifice is off tilt, not quite at the center, not the thing that will make the difference for him. Ergo, the second guy hates the first guy.

On this account, envy is the engine and bane of history. It’s controllable but—sorry Hegel, sorry Kojeve — not curable. Well then, what can control so natural and instinctive a feeling? What, for each of us, would be the “acceptable sacrifice”? Patience, the power to wait — to listen for, and act on — the talents, opportunities and tasks that belong to one’s own life. For that, a right relation to the Creator (or a persistent relation to truth) is a prerequisite.

For this problematic of history, there is no cure. The proposed cure-alls are fantasies, to which Albert Camus responded: “I refuse to kill my brother, for an unreal city in the future.” That’s just what Cain should have said.

Where are we? The Analysts have become somewhat more modest, more scaled down to a humanized reality. The Continentals are either continuing to propose unreal cities in the future, inverting the Master/Slave relation ad infinitum (as if, if you do it again and yet again, that will cure envy) or – in the best case

– looking for a sacrifice,

a way to live in history –

that will prove acceptable.