The Communications of Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra: Tongued With Fire Beyond The Language Of The Living

The media, colloquially referred to by some as, “the liberal media,” is widely known as one of the strongholds of the political left. Combined with the university and our K-12 schools, these institutions are indoctrinating our children towards political liberalism.

While this may be the overwhelming sentiment from these arenas, not everything emanating from them conforms to political liberalism. There are people, places, and yes, even television shows, that defy hegemonic conformation. Two television shows that challenge contemporary liberalism and assume a conservative philosophical position are Avatar: The last airbender (LAB) and The legend of Korra (LOK). The conservative positions of the LAB and the LOK make the universe of the LAB and LOK so refreshing.

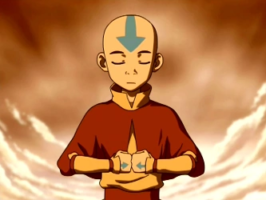

Briefly, for those unfamiliar with the cartoon shows, a synopsis. The LAB and the LOK were created by Bryan Konietzko and Michael Dante DiMartino; they co-exist in the same fictional universe. The series centers around a concept called, “bending.” Bending is the ability to manipulate one of four elements: Water, air, earth, and fire. Only the Avatar is capable of manipulating more than one element, and can in fact bend all four. In addition, the Avatar is endowed with a special power named, “the Avatar state.” The Avatar state is:

“a defense mechanism, designed to empower you with the skills and knowledge of all the past Avatars. The glow is the combination of all your past lives, focusing their energy through your body. In the Avatar State, you are at your most powerful, but you are also at your most vulnerable. If you are killed in the Avatar State, the reincarnation cycle will be broken and the Avatar will cease to exist.” (LAB, season 2, episode 1, hereby referred to as LAB, 2:1).

In the LOK, 2:7 & 8, the audience is given an origin story. In ancient times, Man and the spirits lived together. Man lived in cities, and spirits, meaning ghosts and mythical creatures, in the wild. In order to protect themselves against the spirits in the wild, Man was given the gift of the elements from mythical lion-turtle creatures. Some air, some fire, some water, and some earth.

One day, a man named Wan saw two giant-sized spirits locked together in battle. One cried out for his help, and Wan obliged, freeing the spirit. Unbeknownst to Wan, the spirit he freed was Vaatu, the dark spirit, who was in a perpetual battle with Raava, the light spirit. Wan’s actions caused a powerful darkness to spread across the land, creating a great imbalance in the world. Wan then teamed up with Raava to help restore balance. With Raava’s help, he was able to acquire all four elements from the lion-turtles. Eventually, Wan fused with Raava, and the two became one. Wan is now both Man and spirit. This combination of a person with Raava is what makes the Avatar.

After Wan’s mistake of unleashing evil on the world, he created an imbalance. It is the job of the Avatar to fix this mistake and to maintain balance in the world. Additionally, the Avatar must master all four elements, and eventually, master the Avatar state. With the passage of time, the human portion of the Avatar will die, and the spirit portion will reincarnate itself in another human.

The two series are deeply and profoundly conservative. Several conservative themes running leitmotif are the sacred, including sacred time and the relationship between the dead, the living and the yet unborn; good and evil; family; equity and hierarchy; politics; and tradition. In the following paragraphs, the conservative themes of the two series are explored. The first place to start relates to the Avatar state and the concept of the sacred in the series.

The Sacred

Robert Nisbet defined the sacred as, “the mores, the non-rational, the religious and ritualistic ways of behavior that are valued beyond whatever utility they may possess” (1966, p. 6). Further, the sacred is, “the totality of myth . . sacrament, dogma . . in human behavior” (Nisbet, 1966, p. 221). The sacred’s diametric opposition is the profane (Nisbet, 1966).

While the ideas of sacred ritual and sacred religious practice are prominent throughout, the most important place to start the discussion deals with sacred time, space, and the relationship between the dead, living, and the yet unborn. To the conservative, the dead and the yet unborn are as much a part of society as the living. They have all the same rights and considerations as the living. G.K. Chesterton (1908) called this, “the democracy of the dead.”

Read Sir Roger Scruton’s (1999) interpretation of this concept below:

“The dead and the unborn are as much members of society as the living. To dishonour the dead is to reject the relation on which society is built – the relation of obligation between generations. Those who have lost respect for their dead have ceased to be trustees of their inheritance. Inevitably, therefore, they lose the sense of obligation to the unborn. The web of obligations shrinks to the present tense.”

This is essentially what the Avatar state is, and the relationship the Avatar has with the world at large. It is a duty-centric obligation linking the generations. This generational compact is what makes the Avatar so strong, and it is what makes each succeeding Avatar stronger than the last.

The dead and the yet unborn, while not physically present are still nonetheless with us always. So long as the dead and the yet unborn are in our minds and hearts, we are able to draw strength and inspiration from them. This is why the Avatar is able to have his past lives superimpose themselves over the incumbent Avatar, as both Avatars Roku and Kiyoshi completely transform and overtake Avatar Aang, the Avatar from the LAB’s, body.

Scruton astutely understood the spiritual relationship between the generations. He explained that, “In all societies, rites of passages have a sacramental character. They are episodes in which the dead and the unborn are present” (2017, p. 128). This concept, that of sacred time, is the type of time the Avatar and the Avatar state exist in. This concept is what T.S. Eliot called, “The point of intersection of the timeless With time” (1941, p. 19). The generations and the living connect not in time, but we step outside of time to bond.

As Mircea Eliade wrote, “by its very nature, sacred time is reversible in the sense that, properly speaking, it is a primordial mythical time made present” (1957, p. 68). This type of time, “sacred time, appears under the paradoxical aspect of a circular time, reversible and recoverable, a sort of eternal mythical present that is periodically reintegrated by means of rites” (Eliade, 1957, p. 70). Sacred time moves in a cyclical pattern where time regenerates (Eliade, 1957, p. 80).

Think of the arrow as profane time, and the three circles as sacred time. The points of intersection of the timeless with time are the points on the circles not on the line. They are outside of time itself. The circular time moves cyclically from beginning to end, and then begins anew, while profane time, meaning the arrow, moves from zero, to one, on towards infinity.

One place where sacred time exists in Avatar is the swamp in the Earth Kingdom. As Huu, a swamp bender, described the mystical qualities of the swamp: “Oh the swamp is a mystical place all right. It’s sacred. I reached enlightenment right here under the banyan-grove tree. I heard it calling me, just like you did” (LAB, 2:4). Huu understood that, “In the swamp, we see visions of people we’ve lost, people we loved, folks we think are gone. But the swamp tells us they’re not. We’re still connected to them. Time is an illusion and so is death” (LAB, 2:4). The swamp benders may as well have been reading T.S. Eliot’s 4 Quartets (1941): “Time present and time past Are both perhaps present in time future And time future contained in time past” (p. 1). In the swamp in the LAB, the three protagonists saw a dead relative, a recently deceased young-lady who became the moon-spirit, and the Avatar saw a person he would meet in the future.

These sacred spaces are embodied in things like the sacred temples the fire sages maintain, the spirit oasis in the Northern Water Tribe, and the spirit portals, meaning the doorways, from the profane world to the spirit world. Eliade explained that:

“sacred place constitutes a break in the homogeneity of space . . . this break is symbolized by an opening by which the passage from one cosmic region to another . . . all of which refers to an axis mundi: pillar, ladder . . . around this comsi axis lies the world. . . hence, the axis is located “in the middle,” at the “naval of the earth”; it is the center of the world.” (1957, p. 37)

This principle of the “sacrificial pole, is called the, ‘Pole of Heaven’ and is believed to support the sky (Eliade, 1957, p. 36). The spirit portals prominently featured in the LOK fit this description perfectly.

Remember, as the opposite of the sacred is the profane, the two have an inextricable relationship with each other. The relationship between the two is that the sacred, “stands diametrically opposed to the profane. In fact, one cannot exist in the presence of the other . . . . The sacred either destroys the profane or the sacred becomes contaminated by the presence of the profane” (Allen, 2007, p. 117).

This concept is magnificently illustrated in the climactic scene of the LAB. The Avatar battled the Firelord, and attempted to confiscate his bending, permanently, using a newly acquired technique called, “energy bending.” To, “bend another’s energy, your own spirit must be unbendable or you will be corrupted and destroyed” (LAB, 3, 22). The Avatar’s energy and spirit must be pure, lest his own energy will corrupt and destroy himself. In other words, the profane will contaminate and destroy the sacred.

In season three of Korra, the antagonist, Zahir, poisoned the Avatar using a liquid metal. While the majority of the poison is removed, there remains a lingering amount inside her body. This profanity in her body prevents her from connecting with her spirit, Raava, and also prevents her from entering the Avatar state.

Korra battled Unalaq, the antagonist from Korra’s second season. Unalaq entered the spirit world and managed to fuse with Vaatu, the dark spirit, and become an Avatar himself- a dark Avatar. In their battle, Avatar Unalaq managed to completely rip Raava out of Korra’s body. While they were able to reconnect, Unalaq severed Avatar Korra’s connection to her past Avatars, permanently, essentially left Korra feeling like Burke’s, “flies of a summer” (1790, para. 162), where, “No one generation could link with the other” (1790, para. 162). Simone Weil’s commentary on a lost connection with the past is fitting: “The past once destroyed never returns. The destruction of the past is perhaps the greatest of all crimes” (1949, p. 52).

The empty feelings of alienation and doubt that plagued Korra throughout much of her series were similarly experienced by Aang, after learning that he was the last of his people. The Fire Nation ethnically cleansed the Airbending Nomads in an effort at global domination. The Fire Nation also had a military strategy of capturing and incarcerating benders to prevent resistance. This is a further example of the alienation and estrangement experienced by the characters throughout the shows.

Another word for this phenomenon is “rootlessness.” Simone Weil articulated the phenomenon of being uprooted:

“To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul. It is one of the hardest to define. A human being has roots by virtue of his real, active and natural participation in the life of a community which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain particular expectation for the future. This participation is a natural one, in the sense that it is automatically brought by place, conditions of birth, profession, and social surroundings. Every human being needs to have multiple roots. It is necessary for him to draw wellnigh the whole of his moral, intellectual and spiritual life by way of the environment of which he forms a natural part.” (1949, p. 43)

Haru, an earthbender, expressed the following with sorrow:

“After the attack, they rounded up my father and every other earthbender, and took them away. We haven’t seen them since. . . . Problem is the only way I can feel close to my father now is when I practice my bending. He taught me everything I know” (LAB, 1:6).

The characters in Avatar are uprooted, alienated, and contaminated. They struggle with the issues emmaninanting from this problem. Shills (1981) addressed this issue from both a spiritual, as well as a literal perspective:

To have experienced the disappearance of one’s own biological and cultural censtors . . . without the compensating acquisition of new ones confines a person in his own generation. . . . the unease are not perceived because the vocabulary available to describe this experience is very poor. (p. 327)

The anxiety and alienation the characters in Avatar feel is difficult to articulate because the vocabulary to identify the feeling is often unknown.

Despite the external estrangement and alienation, we can still recover what we have lost. The title of this essay is borrowed from T.S. Eliot’s, Four quartets (1941). Roger Scruton explained the meaning of Eliot’s poem:

“the spiritual tradition that in our daily lives seems dead and buried persists in sacred places and symbols. It is a kind of revelation of the nation and our own social membership, and by opening our hearts to it, and allowing the present moment to fill with the residue of time past, we recuperate what we might have lost.” (2018, p. 92)

And this notion, of looking within our hearts, opening them to the possibilities of the sacred, is a central theme in the LOK.

In season two, Korra and team Avatar must enter the spirit realm. Jinora, Avatar Aang’s granddaughter and friend to Korra, has a strong connection with the spirits. She is capable of seeing spirits in our physical world, unlike most people. She can see and connect with the spirits because they are all around us. Jinora can see them because she opens her heart to the possibility.

After the climax of season two, Korra contemplates closing the spirit portals, but instead allows them to remain open. The spirits now live in the physical world with Man. The spirits are all around us in Avatar; their physical manifestation no longer adheres to the belief that they are hidden.

This concept is corroborated in the LAB, 1:7. Aang enters the spirit world and takes a ride on Avatar Roku’s spirit animal, his dragon, Fang. Iroh, a member of the Royal Fire family, saw the Avatar riding the dragon with astonishment. Only Iroh could see him. Later, in season one, Admiral Zhao, one of the season’s main antagonists, said, “I know you fear the spirits, Iroh. I’ve heard rumors about your journey into the Spirit World” (LAB, 1:23). Iroh believes in spirits and the spirit world, and because of his open mind and heart, he was able to see the Avatar in the spirit world while no one else could.

Good and Evil

A major theme in the two series is the struggle between good and evil. In each season, there is a clear conflict between good and evil, light and dark, and right and wrong. This struggle is not just external, but also an internal struggle between our good and evil inclinations.

Jean Rousseau is the godfather and patron saint of liberalism. He believed that, “man is naturally good, and that is solely by these institutions that men become wicked” (Rousseau, 1762, p. 2). We, as human beings, are born benevolent, but we are corrupted by society; evil comes from without, via society. This is the most important premise in liberalism, and the single most importance incongruence between liberalism and conservatism. Conservatives believe in an ethical dualism: The figurative angel on one shoulder, and the devil on the other. Through our choices, we choose to be good, or we choose to be evil (Babbitt, 1924).

In the Avatar universe, the struggle is portrayed between Man and Man, Man and spirit, and an inner struggle between our good and evil inclinations. Whether it is the spirit battle between Raava and Vaatu, the battle against the evil Fire Nation, or the various villains of Korra, the struggle between good and evil is stark and unmistakable.

The most visible struggle of someone wrestling with their evil inclination occurs within Prince Zuko, an antagonist turned hero in the LAB. In a dream, two dragons, one red and one blue, represent his good and evil inclination wrestling inside his psyche. Zuko’s uncle, Iroh, told Zuko the following:

Because understanding the struggle between your two great-grandfathers can help you better understand the battle within yourself. Evil and good are always at war inside you, Zuko. It is your nature, your legacy. But, there is a bright side. What happened generations ago can be resolved now, by you. Because of your legacy, you alone can cleanse the sins of our family and the Fire Nation. Born in you, along with all the strife, is the power to restore balance to the world. (LAB, 3:6)

In the same episode, Avatar Aang had a vision from the previous Avatar, Roku. Roku tells Aang the story of his relationship with a previous Firelord, Sozin. Aang understood the meaning of Roku’s vision to be the following: “Roku was just as much Fire Nation as Sozin was, right? If anything, their story proves anyone’s capable of great good and great evil” (LAB, 3:6).

This struggle between good and evil, both internal and external, is something that arises in every generation. It is a permanent aspect of the human condition. As Avatar Wan asked Raava, “If you and Vaatu have the same fight every ten thousand years, why hasn’t one of you destroyed the other?” Raava answered: “He cannot destroy light, anymore than I can destroy darkness. One cannot exist without the other” (LOK, 2:6).

Toph, a child protagonist from the LAB and an elderly woman in the LOK, recollected on the present condition compared with her time as chief of police. She told Korra:

“Listen, when I was Chief of Police in Republic City, I worked my butt off busting criminals. But did that make crime disappear? Nope. If there’s one thing I learned on the beat, it’s that the names change, but the street stays the same.” (LOK, 4:3)

Essentially, the struggle for good and evil is an ineradicable struggle. It will always exist in the world. This is what T.S. Eliot (1939) referred to as one of the, “permanent things.” It is precisely this that makes Avatar so timeless and classic: it speaks to the fact that human nature is constant, that the human condition is tragic, and that good literature speaks to those two aspects of life (Kirk, 1989). We, in the present, are no different than any other generation because human nature is constant and unchanging. This constancy of human nature causes the same issues to arise in every generation as permanent fixtures of the human condition, i.e., the permanent things.

Toph understood this facet of evil. Amon, the antagonist from season one of Korra, did not. Amon’s brother, Tarrlok, believed that Amon understood bending to be the source of evil. This view is nearly identical to Rousseau’s, who believed that society is the source of evil, and not Man’s fallen nature. Amon could invalidate a person’s bending. By eliminating bending, the source of evil according to Amon, he could completely eradicate all evil.

Family

Another incongruence between liberalism and conservatism is how each philosophy views the central unit of society. What is a civilization composed of? Liberals believe we are a nation of individuals, loosely coupled for contractual obligations and benefice; conservatives believe we are not a civilization of individuals, but rather, a civilization of families (Nibset, 1966).

The Avatar series is a family affair. Every major character in Avatar is attached to a family. Every major plot involves conflicting siblings, parents, and extended clan and kin either teaming up or fighting.

When the family is the central unit of civilization, it sets the tone for the course of life, discourse, and action. As Edmund Burke opined:

“Parents may not be consenting to their moral relation; but consenting or not, they are bound to a long train of burthensome duties towards those with whom they have never made a convention of any sort. Children are not consenting to their relation, but their relation, without their actual consent, binds them to its duties; or rather it implies their consent because the presumed consent of every rational creature is in unison with the predisposed order of things.” (1791, p. 161)

Burke understood the nature of family and obligation. Our families are duty centric institutions. Many times, we have desires we must temper to fulfill our duties which antecede and supplant our selfish indulgences. We cannot pick and choose when and how we must help and serve our families, but rather, must accept these duties as non-negotiable aspects of life. Burke knew that, “Duties are not voluntary. Duty and will are even contradictory terms” (1791, p. 159).

The characters in Avatar are both family-centric and duty bound. Whether it’s Princess Yue, who sacrificed herself for her people, the Avatar’s duty to serve the world, or the sages at the temple tasked with preserving the legacy of the Avatar, duty is a strong theme.

As Avatar Aang wrestled with the thought of killing Firelord Ozai, he meditated to connect with his previous lives. He connected with Avatar Yangchen, a fellow airbender. With stoicism, Avatar Yangchen firmly told Aang:

“Avatar Aang, I know that you’re a gentle spirit, and the monks have taught you well, but this isn’t about you. This is about the world. Many great and wise Air Nomads have detached themselves and achieved spiritual enlightenment, but the Avatar can never do it. Because your sole duty is to the world. Here is my wisdom for you: Selfless duty calls you to sacrifice your own spiritual needs, and do whatever it takes to protect the world.” (LAB, 3:19)

The Avatar never asked to be the Avatar, but nonetheless, the Avatar has duties to the world. Avatar Yangchen and Edmund Burke are kindred spirits on this issue: “In some cases the subordinate relations are voluntary, in others they are necessary—but the duties are all compulsive” (Burke, 1791, p. 167). We do not always negotiate for our positions in life, but irrespective of that fact, our duties are non-negotiable and mandatory to perform.

Just as the family is duty-centric, the family unit is also hierarchical. As parents are always superiors to children, children are socialized from a young age to understand that hierarchies are moral and just, a concept conservatives value significantly more than liberals (Haidt, 2013).

Throughout each series, the Avatar is on a constant quest to master the elements, always through the tutelage of a master. Every element the Avatar needs to master, the Avatar must subject his or herself to the authority of a superior.

And in the same sense of the natural and just authorities of families and masters, the Avatar series believed in monarchy and aristocracy. The Royal Fire family in the LAB is a drama centered on monarchy and aristocracy. Burke (1791) defended aristocracy by saying that:

“To be bred in a place of estimation; To see nothing low and sordid from one’s infancy; To be taught to respect one’s self; To be habituated to the censorial inspection of the public eye; To look early to public opinion. . . . To have leisure to read, to reflect, to converse; To be enabled to draw the court and attention of the wise and learned wherever they are to be found. . . . To be taught to despise danger in the pursuit of honour and duty. . . These are the circumstances of men, that form what I should call a natural aristocracy, without which there is no nation.” (p. 168)

For Burke, as well as team Avatar, aristocracy and monarchy are essential. Burke followed this by adding that we must, “give therefore no more importance, in the social order, to such descriptions of men, than that of so many units, is an horrible usurpation” (1791, 169). Burke articulated the importance of class-structure, as it is the natural order of Man. In Avatar, there are classes and orders like the fire sages, the monks, the aristocracy, and even the secret orders, like the White Lotus, and its foil, the Order of the Red Lotus.

The Politics of Avatar

In the LOK, politics are more important than in the LAB. In the LAB, the central political theme is fascism, plain and simple military domination of one group over the other. While there are subtleties and nuances to the story, it is largely straightforward.

The LOK is more nuanced. The first villain, Amon, is a radical socialist, desiring equality. The second villain, Unalaq, is a theocratic super-villain desiring spiritual domination. Zaheer, the antagonist from the third season, is an anarchist, desiring chaos and the destruction of the Avatar forever. The fourth villain from Korra, Kuvira, is another fascist. Amon and Zaheer are among the two most important villains to discuss, as their motives and means are the most complicated.

Concerning Amon, his quest for equity would only come at the expense of taking bending from the benders. Through his superior blood-bending ability, an ability where a water bender can control the physical body of other humans by bending the water/blood in the human body, he was able to suppress a bender’s ability to bend. Through this course of action, Amon is not bringing others up, but instead, yanking others down. This is the hallmark of the emotion of envy. When it is not about someone rising to the level of another person, but about the lower person yanking the higher person down; when it is not about someone having what another person has, but about the other person not having it altogether; and when it is not about someone winning, but about another losing, we have envy on our hands (Shoeck, 1966; de la Mora, 1987).

Equity is the politics of envy. Attempting to make an inequitable world an equitable one will only create more problems than those already extant. Russell Kirk (1955) strongly rejected the doctrine of equity socialism espoused:

“Equity benefits no one. It frustrates men of talent and it reduces the poor to a poverty still more abject. . . . For inequality produces the wealth of civilized communities: it provides the motive which induces men of superior abilities to exert themselves for the general benefit.” (p. 403)

Kirk, at a later date, revealed the latent utopianism of socialism: “the belief that this world of ours may be converted into the Terrestrial Paradise through the operation of positive law and positive planning” (Kirk, 1989, p. 54). This paradise on Earth is all accomplishable because of Rousseau’s natural goodness of Man.

The natural goodness of Man was the surface level of Rousseau’s ideology. On a deeper level, Rousseau really invalidated the doctrine of Original-Sin, where Man’s punishment was banishment from Eden, a utopia on Earth (Kessler, 2018). Without Original-Sin, utopia is now a possibility. The socialists believe they can create a paradise here on Earth, a place traditionally reserved exclusively for the heavens (Kessler, 2018).

Firelord Ozai, who planned to literally burn everything to the ground and rebuild over it in his image, exclaimed: “Fire Lord Ozai is no more. Just as the world will be reborn in fire, I shall be reborn as the supreme ruler of the world. From this moment on, I will be known as . . . the Phoenix King” (LAB, 3:18). Hiroshi Sato, the billionaire industrialist who funded Amon and the equalists, said something similar: “They took away your mother, the love of my life. They’ve ruined the world, but with Amon we can fix it and build a perfect world together” (LOK, 2:7). Both the Firelord and Hiroshi Sato believe they have the capability to cleanse the world of imperfections, and create a terrestrial paradise conforming to their visions.

In season three of Korra, the antagonist is an anarchist name Zahir. His goal was to destroy all forms of government, nations, and to kill Korra while she’s in the Avatar state, thus permanently ending the Avatar cycle. Zahir, and his Red Lotus disciples, sound eerily reminiscent to what Rousseau professed in, The social contract (1762), concerning freedom:

“This single item in the compact can give power to all the other items. It means nothing less than that each individual will be forced to be free. It’s obvious how forcing comes into this, but. . . to be free? Yes, because this is the condition which, by giving each citizen to his country, secures him against all personal dependence, i.e. secures him against being taken by anyone or anything else.” (p. 9)

Zaheer, like Rousseau, wanted to force everyone to be free. One of his successful efforts in this endeavor was his regicide of the Earth Queen. He told the Earth queen: “I don’t believe in queens. You think freedom is something that you can give or take on a whim? To your people, freedom is just as essential as air. And without it, there is no life. There is only . . . darkness” (LOK, 3: 10). Zaheer, a powerful airbender, used his airbending to vacuum the oxygen out of the Earth Queen’s body, asphyxiating her.

Zaheer then hijacked the city’s radio station and made the following announcement:

“Moments ago, the Earth Queen was brought down by the hands of revolutionaries, including myself. I’m not going to tell you my name, because my identity is not important. I’m not here to take over the Earth Kingdom. I think you’ve had enough of leaders telling you what to do. It’s time for you to find your own path. No longer will you be oppressed by tyrants. From now on, you are free! I deliver Ba Sing Se be into the hands of the people!” (LOK, 3:10)

And what happened after that? Pandemonium! The city descended into chaos, looting, and rioting. Zaheer got his wish.

And this is what made Zaheer such a good foil for the Avatar: The Avatar’s real responsibility is maintaining balance and order in the world. Zaheer’s goal was chaos. Simone Weil understood the importance of order: “The first of the soul’s needs, the one which touches most nearly its eternal destiny, is order” (1949, p. 10). Zaheer was right in saying, “And without it, there is no life. There is only . . . darkness” (LOK, 3:10). Russell Kirk, in The roots of American order, wrote near identical prose. Kirk warned that without, “order in the soul and order in society, we dwell, ‘in a land of darkness, as darkness itself,’ the book of Job puts it, ‘and of the shadow of death, without any order, and where light is as darkness’” (1974, p. 3).

Order is everything acting harmoniously with everything else (Kirk, 1974). Order does not mean equality, nor does it imply happiness, but rather everything in its proper place. We rarely recognize order, but we always recognize chaos. This is the duty of the Avatar: To maintain balance and prevent this world and the spirit world from descending into chaos.

Tradition

Another conservative element in the Avatar universe is the emphasis on tradition. Sir Roger Scruton (2018) understood traditions to be:

“Solutions, tested by time and custom, to the problems of social conflict and the needs of orderly government. It is the persistence of these institutions over time and their inscription in the hearts of the . . . people that have created the love of liberty.” (p. 25)

To Scruton, traditions are not, “arbitrary rules and conventions” (p. 48). They are infinitely more than that. Traditions are our society collectively, “discussing answers that have been discovered to enduring questions. These answers are tacit, shared, embodied in social practices and inarticulate expectations” (p. 48). Traditions are, “forms of knowledge. They contain the residues of many trial and errors, and the inherited solutions to problems that we all encounter” (p. 47).

In the second season of the LOK, the emphasis of the season is the Avatar’s connection with the spirits, as well as the spirit world in general. As they celebrated the northern lights at their winter carnival, Korra’s father said, “Traditions change. It’s not the end of the world.” His brother, and Korra’s uncle, Unalaq, understood the implicit value of traditions: “Tell that to the sailors who are being attacked by angry spirits in southern waters. Some traditions have purpose” (LOK, 2:1).

Unalaq understood the implicit value in traditions that Scruton spoke of. Essentially, Unalaq knew there was some implicit purpose to our traditions, and that they were not arbitrary social constructs. What is being alluded to here is a concept known as “Chesterton’s fence” (1928). G.K. Chesteron once offered:

“In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, ‘I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.’ To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: ‘If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.’” (1929)

Unalaq is reluctant to change traditions because of the implicit purpose they might embody, which may be unbeknownst to us.

Ultimately, what the Avatar universe is telling its audience is that our traditions serve a purpose. They are not, “the pompous fabrications of . . . ancestors . . .” (Kirk, 1989, p. 17). When people assume traditions and the norms they are predicated on are hollow superstitions, “then every rising generation will challenge the principles of personal and social order” (Kirk, 1989, p. 17). People who challenge these norms, these customs, and these traditions, “will learn wisdom only through agony” (Kirk, 1989, p. 17). The sailors being attacked by angry spirits are the ones learning this wisdom through agony.

Our traditions are, “what is to be handed down . . . that aspect of humanity which remains the same, maybe even man’s ‘essence’ (Pieper, 2008, p. 10). The unchanging fixtures of the human condition, i.e., the permanent things, are what link the generations. These traditions prevent Burke’s “flies of summer.”

While maintaining traditions is important, the Avatar universe recognizes that traditions can evolve and improve. As Burke knew, “A state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation” (1790, para. 36). That change cannot be drastic and destructive, but rather, a wise reformer has, “A disposition to preserve, and an ability to improve” (Burke, 1790, para. 262).

The desire to maintain continuity while improving existing things is wonderfully displayed in season 4 of Korra. The new airbenders have now abandoned the traditional gliders (think minnie, personal, hang gliders), and are now using winged flight-suits. These suits have webbing from the sleeves to roughly the waist that serve the same purpose as the gliders, but supplant it with new technology. Still, at the same time, the wingsuits maintain the color scheme of the ancient Air Nomads, linking the generations, preventing the flies of summer.

Conclusion

As Russell Kirk taught, “Fiction is truer than fact: I mean that in great fiction we obtain the distilled wisdom of men of genius, understandings of human nature which we could attain . . . unaided by books, only at the end of life, after numberless painful experiences” (p. 7). Kirk illuminated the purpose of a classical education as, “the study of the greatness and limitations of human nature” (p. 7).

Bruno Bettleheim, a psychologist, explained the real purpose of children’s fairy tales.

Bettelheim (1989) informed us that, “Wisdom does not burst forth fully developed. . . . It is built up, small step by small step, from most irrational beginnings” (p. 3). Bettelheim believed this was the purpose of fairy-tales and other children’s stories. They teach our children, “not to be at the mercy of the vagaries of life. One must develop one’s inner resources, so that one’s emotions, imagination, and intellect mutually support and enrich one another” (p. 4). The goal is to provide, “a moral education which subtly, and by implication only, conveys . . . the advantages of moral behavior” (p. 5).

The creators of Avatar understood these aspects of great works of fiction and education, and implemented them in their wonderful, rich, and purposeful fictional universe. Team Avatar chose to speak to the constancy of the human condition, the permanent things and fixtures of human nature, and ultimately, they chose not to write something new, but something perennial.

T.S. Eliot once instructed future poets and authors on how to write great works of literature:

“One error, in fact, of eccentricity in poetry, is to seek for new human emotions to express; and in this search for novelty in the wrong place it discovers the perverse. The business of the poet is not to find new emotions, but to use the ordinary ones.” (1919, p. 42)

Eliot understood that great works of fiction are not new, but rather, are ancient. To write good literature, do not attempt to write something novel, but rather, write something that is familiar. Write something that speaks to the constancy of the human condition. Draw something that illustrates what happens when we let our passions and appetites run amok, unrestrained. Tell a story that showcases the ancient and eternal struggles between Man and Man, Man and nature, Man and spirit, and most of all, the struggle for good and evil in the breast of every individual.

Through Avatar: The last airbender and The legend of Korra, we see the greatness and limitation of human beings. We see the struggle for good and evil in the breast of the individual, and we see what is permanent. The two shows are not merely fantasy and action, but rather, are reality and human nature. Avatar reminds us of what it means to be a human being. Avatar reminds us of how important our duties to piety are, how important family is, and ultimately, how important the force of good triumphing over evil is.

Only through a conservative scholarly lens are the themes and messages of Avatar visible. By recognizing the conservative elements of Avatar, we can truly hear what team Avatar is saying to us: That the communication of the Avatar is, “tongued with fire beyond the language of the living” (Eliot, 1941).

Works Cited

Allen, K. (2007). The social lens: An invitation to social and sociological theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Bettelheim, B. (1989). The uses of enchantment: The meaning and importance of fairy tales. New York, NY: Random House.

Burke, E. (1991). Letters on a regicide peace. Indianapolis, IN: The Liberty Fund.

. (1790). Reflections on the Revolution in France. Retrieved from http://www.bartleby.com/24/3/6.html

Chesterton, G.K. (1930). The thing: Or why I am a Catholic. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead, and CO.

Eliot, T.S. (1943). Four quartets. Orlando, FL: Harcourt inc.

. (1919). Tradition and individual talent. Perspecta. Retrieved from http://docenti.unimc.it/sharifah.alatas/teaching/2014/2000004080/files/l37- iim/tradition_and_individual_talent.pdf

. (1984). Enemies of the permanent things. Peru, IL: Sherwood, Sugden, and CO.

. (1973). The revitalized college: A model. The Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal. Retrieved from http://www.kirkcenter.org/detail/therevitalized-college-a-model

. (1986). Introduction. In I. Babbitt, Literature and the American college (pp. 1-68). Washington, DC: National Humanities Institute.

. (1981). The moral imagination. Literature and Belief. Retrieved from http://www.kirkcenter.org/index.php/detail/the-moral-imagination/

. (1974). The roots of American Order. Wilmington, DE: ISI Books.